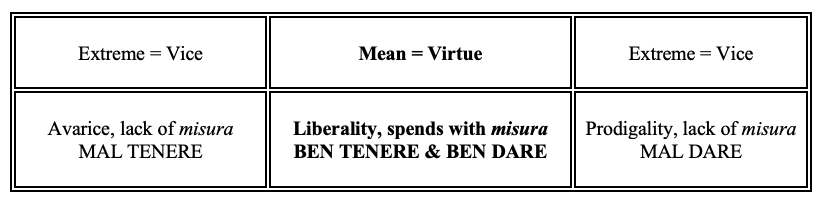

- Aristotle’s philosophy is used in Inferno 7 in a way that signals Dante’s willing dependence on the Greek philosopher’s system of ethics

- Dante introduces the Aristotelian concept of virtue as a mean, from the philosopher’s Nicomachean Ethics

- He does so not through discussion but through dramatic action: in his fourth circle Dante includes both the sins of avarice and prodigality; whereas, if he had been following the Christian template of the seven deadly vices, this circle would include only avarice

- For Aristotle the virtue of liberality is the mean between the vicious extremes of avarice on the one hand and of prodigality on the other

- Both groups of sinners in the fourth circle, the misers and the prodigals, approach wealth and money in an immoderate way, without temperance, without misura: “con misura nullo spendio ferci” (no spending that they did was done with measure [7.42])

- Misura is the vernacular term that Dante uses for the ability to master one’s desires and to exert temperance, moderation, and self-control: “continence” for Aristotle

- Lack of misura, succumbing to excess desire, “incontinence” for Aristotle, will be introduced as a category of sin in Dante’s hell in Inferno 11, where we learn that circles 2-5 of Dante’s hell house sins of “incontenenza” (11.82)

- Dante had established the philosophical premises for an Aristotelian template on wealth management already in his moral canzone Le dolci rime (circa 1294)

- Aristotelian ethical thinking is non-dualistic, based on a spectrum of behavior with virtue at the mean; Christian ethical thinking is traditionally based on binaries between vice and virtue (see Dante’s Purgatorio for the Christian binaries of vice and virtue on each terrace)

- Anti-clericalism is introduced in this circle, through the inclusion of popes and cardinals among the misers

- The de-classicizing — Christianizing — of Fortuna: the classical goddess Fortuna is now a minister of divine Providence

- Dante’s reworking of Fortuna connects to Inferno 6 and to the revelation of Dante’s exile: the Christianizing of Fortuna is a way for Dante to stem social anxiety as a member of a marginal family who is now also a stateless exile

- Appendix 1 on the philosopher and astrologer Cecco d’Ascoli, who in his philosophical poem Acerba accuses Dante of determinism, with a long passage on Inferno 89

- Appendix 2 on Dante’s canzone Poscia ch’Amor (circa 1295) and Inferno 7

[1] Inferno 6 ends with a discussion that is overtly Aristotelian: as discussed in the Commento on Inferno 6, on the previous canto, the issue of a being’s “perfection” is rooted in Aristotelian philosophy. Inferno 7 begins with the need to placate the classical monster-guardian Plutus (not Pluto, the god of the underworld, but Plutus, god of wealth, son of Demeter and Iasion), who stands watch over the fourth circle. The presence of Plutus is akin to the presence in previous scenes of the classical monster-guardians Charon, Minos, and Cerberus.

[2] Plutus shouts out a challenge to the travelers in a garbled mixture of Greek and Hebrew:

“Pape Satàn, pape Satàn aleppe!”, cominciò Pluto con la voce chioccia (Inf. 7.1-2)

“Pape Satan, Pape Satan aleppe!” so Plutus, with his grating voice, began.

[3] Here we are faced with a striking example of Dante’s willingness to create cultural hybrids, in this case in language: the repetition of “pape” in Plutus’ exclamation subliminally prepares us for the presence of popes — “pope” in Italian is “papa” — among the sinners of this circle. At the same time, since this is an infernal hybrid, the verses also demonstrate the reversals that are so common in Dante’s treatment of classical culture, as he veers from positive to negative and back again. At the end of Inferno 6, Aristotle’s philosophy and language provide the “scïenza” that the pilgrim needs in order to better understand his experience, and indeed Virgilio exhorts the pilgrim: “Ritorna a tua scïenza” (Turn back to your science [Inf. 6.106]). Aristotle is the “maestro di color che sanno” (the master of those who know [Inf. 4.131]), as Virgilio is “quel savio gentil, che tutto seppe” (that gentle sage, who knew everything [Inf. 7.3]), in the third verse of this very canto.

[4] Conversely, now, at the beginning of Inferno 7, Aristotle’s language, Greek, is used by Dante, in a pastiche with Hebrew, to compose Plutus’ degraded infernal language, a monstrous form of self-expression. Although Greek and Hebrew were languages that Dante did not know, he had access to medieval glossaries that provided rudimentary knowledge of their forms and sounds. We will see quite a few “harsh rhymes” in this canto, in a kind of opening salvo of the tonality that we will find in much of lower Hell. Eventually, the poet will explicitly thematize his need to seek out “harsh and grating rhymes” in order to compose a representation of hell, claiming that the task of writing hell requires “rime aspre e chiocce” in the first verse of Inferno 32. The infernal stylistic category of rime aspre e chiocce, confirmed in Inferno 32.1, is first openly presented here, in Plutus’s grating “voce chioccia” (harsh voice) of Inferno 7.2.

[5] Thus, in the transition from Aristotle as the supreme philosophical authority at the end of Inferno 6 to the classical monster Plutus at the beginning of Inferno 7, Dante views classical culture in swift succession both positively (in bono) and negatively (in malo). This kind of veering or juggling is a hallmark of Dante’s conflicted treatment of classical culture: as an early humanist, he reveres classical culture; at the same time, he is also highly conscious of its defects with respect to Christianity.

[6] But, for all the ostentatious distancing from classical culture that Dante effects at the outset of this canto, Aristotle’s presence in Inferno 7 is very strong, stronger even than his presence at the end of Inferno 6. For Aristotle is used in Inferno 7 in a way that signals Dante’s willing dependence on the Greek philosopher’s system of ethics. For the first time, we begin to see what the poet will tell us only in Inferno 11, namely that Dante uses Aristotle’s Ethics as a source and organizational template for his hell. For the first time, we begin to have insight into the Aristotelian weight of the word mezzo in the first verse of the poem.

[7] How does Dante signal, in Inferno 7, his willing dependence on Aristotle’s system of ethics? In his treatment of avarice and prodigality in Inferno 7, Dante engages the idea that virtue is the mean: “mezzo”. He was familiar with this idea; indeed, he had used the word “mezzo” for “mean” when he translated Aristotle on virtue as the mean from Latin into Italian in his canzone Le dolci rime, written circa 1294: “Quest’è, secondo che l’Etica dice, / un abito eligente / lo qual dimora in mezzo solamente” (This is, as the Ethics states, a “habit of choosing which keeps steadily to the mean” [Le dolci rime, 85–87; Foster-Boyde trans.]).

[8] Much of my commentary on Inferno 7 will be devoted to exploring its Aristotelianism, centered on the concept misura. Misura, I hold, is the vernacular equivalent of Aristotelian “continence”: the temperance, moderation, and self-control that, when lacking, is called “incontinence” (akrasia in Greek) in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. A fuller discussion of the cultural context, the transmission of these ideas through Cicero and Dante’s reception of them, may be found in “Aristotle’s Mezzo, Courtly Misura, and Dante’s Canzone Le dolci rime,” cited in Coordinated Reading.

[9] We have reached the fourth circle, the home of the shades who sinned through avarice and through prodigality. These sinners are misers who held onto their material goods excessively and prodigals who spent their material goods inordinately. In Wordsworth’s words: “Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers” (The World Is Too Much With Us).

[10] In Inferno 7, Dante treats both kinds of excess in human wealth management and makes clear that both are sins: holding onto wealth too much (avarice) and holding onto wealth too little (prodigality) are equally sinful. Both forms of excess constitute a lack of misura: a lack of temperance, of moderation, of continence. One formula therefore covers both types of excess, both avarice and prodigality, a formula based on misura that is equally applicable to both misers and prodigals: “con misura nullo spendio ferci” (no spending that they did was done with measure [Inf. 7.42]).

[11] Conceptualizing the fourth circle of his hell as devoted to both misers and prodigals, Dante departs from the traditional Christian template of the seven deadly vices. The seven vices include avarice, but not prodigality. What has happened to cause Dante’s divergence? It is my belief that the answer lies in his willing adherence to the concept of misura, a concept already loosely present, through Cicero, in vernacular poetry and prose, and one onto which Dante, versed in Aristotle’s Ethics, deliberately grafts full Aristotelian meaning. (This is my argument in the essay “Aristotle’s Mezzo”; see Coordinated Reading)

[12] Dante views the moral pathology of these sinners as excess, whether it be excess in grasping and holding material goods or excess in wasting and dissipating them: his point is that “Getting and spending” are equally problematic, and equally cause us to “lay waste our powers”. The sinners of this circle showed no misura in their handling of wealth.

[13] Misura is a quality of mind that is balanced, proportionate, and moderate with respect to desire; the possession of misura results in self-control. Dante introduces the concept of misura to the Commedia here, in the context of wealth management, of human attitudes toward the conservation or dissipation of wealth. The word misura appears for the first time in Inferno 7: “con misura nullo spendio ferci” (no spending that they did was done with measure [Inf. 7.42]).

[14] We will find the negative variant of misura, the word dismisura — lack of measure, lack of moderation — in Inferno 16 and in Purgatorio 22. In Inferno 16 the context is a discussion of the nouveaux riches who corrupt Florence with their arrogance and immoderate excess: “orgoglio e dismisura” (Inf. 16.74). In Purgatorio 22 Dante confirms his commitment to the ethical scheme implicit in Inferno 7, showcasing the term dismisura again in the context of Mount Purgatory’s terrace of avarice and prodigality:

Or sappi ch’avarizia fu partita troppo da me, e questa dismisura migliaia di lunari hanno punita. (Purg. 22.34-36)

Know then that I was far, too far from avarice — it was my lack of measure that thousands of months have punished.

[15] Up to this point the reader of Inferno might plausibly have believed that Dante’s Hell is organized in a way that loosely accords with the Christian scheme of the seven deadly sins — more properly called the seven capital vices, as noted in the Commento on Inferno 6. The first circles of Hell do in fact overlap with the least grievous of the seven capital vices, traditionally ordered thus: pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, lust.

[16] If we were to organize the seven capital vices from least to most grievous, we would begin with lust, proceed to gluttony, and then to avarice — just as we proceed through circles 2 to 4 of Dante’s Hell. Given that hell punishes sin, rather than vice, the second circle of hell punishes sins of lust caused by the vice lussuria (in Francesca’s case, fornication in an adulterous affair with her brother-in-law), and the third circle punishes sins of gluttony caused by the vice gula.

[17] Now that we have passed through the circles of lust (circle 2) and gluttony (circle 3), it would be natural to expect to find that the next circle is the circle of avarice. But instead we find avarice yoked to prodigality, although prodigality—which appears coupled with avarice in both Inferno and Purgatorio—is not one of the seven capital vices. Only avarice is.

[18] In the essay “Aristotle’s Mezzo” (cited in Coordinated Reading), I discuss the significance of Dante’s inclusion of prodigality alongside avarice in the fourth circle of his Hell and the critical blind spot regarding the larger manifestations of Aristotle’s presence in this canto:

While the commentaries draw attention to the Aristotelian mean when glossing the specific verse “che con misura nullo spendio ferci” (Inf. 7.42), there is a critical blind spot vis-à-vis the larger manifestations of Aristotle’s presence in Inferno 7: for instance, why are the prodigals here with the misers? Only Aristotle and an ethical system based on a spectrum in which sin is the extreme — in this case avarice is one extreme and prodigality the other — and virtue is the mean can account for the provocative and rarely discussed pairing of prodigals and misers in the fourth circle of Dante’s hell. As Dante says, these souls are gripped by opposing sins, which force them constantly to move “da ogne mano a l’opposito punto” (from each side toward the opposite point; Inf. 7.32); they are divided by sins that are contrary to each other: “colpa contraria li dispaia” (contrary sin divides them; Inf. 7.45). From the moment that we are shown two groups of opposed sinners in the fourth circle, prodigals as well as misers, we need to be aware that we are not operating in a univocally Christian ethical framework. We should already be able to infer, long before reaching Inferno 11, that these first circles of hell are not simply governed, as their order might have induced us to believe, by the system of the seven capital vices, for that system does not include prodigality. (“Aristotle’s Mezzo”, p. 168)

[19] We need to ask the question: how do we account for the presence of prodigals here? The answer is quite remarkable and certainly warrants more critical attention: the model of vice and virtue that Dante has adopted in Inferno 7 — and even more remarkably, later in Purgatorio 21-22 — is not Christian. In other words, while it is commonplace to note that the presence of prodigality signals that Dante is here viewing sin through an Aristotelian lens, we have to take a further step and state clearly: the ideological system adopted for this section of a Christian hell is not Christian.

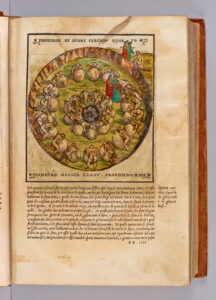

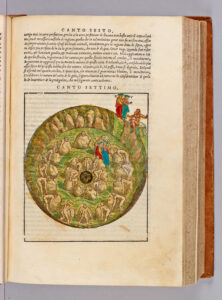

[20] According to Aristotle, virtue is located at the midpoint of human behavior (the “golden mean”) and vice is located at the extremes. The vicious extremes with respect to handling wealth are avarice at one end of the spectrum and prodigality at the other. The virtuous man is at the midpoint and is “liberal” (generous) rather than either prodigal or miserly. He knows how to treat material goods without excess; he is able to engage material goods with temperance, with moderation.

[21] Dante’s version of Aristotle’s doctrine indicts the sinners of the fourth circle for excessive giving away of material goods (“mal dare”) and for excessive holding onto material goods (“mal tener”): “Mal dare e mal tener lo mondo pulcro / ha tolto loro” (Ill giving and ill keeping have robbed both / of the fair world [Inf. 7.58-9]). Dante thus offers the extreme of mal dare (prodigality) at one end of the spectrum and the extreme of mal tenere (avarice) at the other, and implies a virtuous midpoint at which wealth is treated with liberality, according to misura.

[22] Dante emphasizes his deployment of a paradigm built on two extremes by constructing a contrapasso in which there are two groups of souls who move toward each other along two halves of one circle pushing weights; when they meet they hurl opposing insults at each other, calling out “Why do you hoard?” and “Why do you squander?” (verse 30). In this way Dante constructs the two groups of sinners as opposites but analogous: “Così tornavan per lo cerchio tetro / da ogne mano a l’opposito punto” (So did they move around the sorry circle / from left and right to the opposing point [Inf. 7.31-2]).

[23] The two groups of souls in Inferno 7 are conjoined and mirrored opposites. He thus presents the two groups of souls in Inferno 7 as conjoined but opposites. They move along one circle but as two opposing cohorts. They move in opposite directions, but always toward each other — toward the mean that they were unable to reach in life: “da ogne mano a l’opposito punto” (from left to right to the oppsing point [Inf. 7.32]). The sins that separate these souls into two groups are “contrary” to each other: ”colpa contraria li dispaia” (their opposing guilts divide their ranks [Inf. 745]). Dante’s descriptions consistently emphasize the two groups of souls as opposite: “oppostito punto” (32}, “colpa contraria” (45), “due cozzi” (55).

[24] Through the contrapasso that he devises, Dante draws in space the idea of an ethical spectrum with vice at either extreme and virtue at the midpoint. The virtuous midpoint that resides between the two vicious extremes of mal dare and mal tenere is Aristotle’s liberality. In the language of Inferno 7, we could say that there is an implied “ben dare” and “ben tenere” that marks the mean.

[25] Dante’s version of the Aristotelian paradigm, with respect to avarice and prodigality, can thus be outlined as follows:

[26] This paradigm — the mean as virtue with two extremes of vice on either side — is of course extended by Aristotle to contexts other than the handling of wealth, as illustrated by the chart of the Nicomachean Ethics attached below.

Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics. translation by J.A.K. Thomson. London: Penguin Books, 2004. pp.285-6.

[27] In sum, the presence of prodigals in the fourth circle of Hell indicates that Dante has here adopted an Aristotelian template that he interweaves throughout his Inferno with Christian ideology. This move also prepares us for the stunning revelation of Inferno 11, where Virgilio explains that Hell is structured according to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

[28] In other words, in Inferno 11 we learn that the interweaving of Aristotle with Christian ideology in Dante’s Inferno is programmatic, not a singular occurrence. The presence of the word misura in Inferno 7 also serves to anticipate Inferno 11; it is in canto 11 that the Aristotelian equivalent “incontenenza” is unveiled. As already noted, misura is for Dante effectively the vernacular expression of the Aristotelian concept of continence, as dismisura is the vernacular expression of incontinence.

[29] The philosophical premises for treating wealth management according to an Aristotelian template are already set up by Dante in the canzone Le dolci rime (written circa 1294), where Dante embraces the Aristotelian concept of virtue as the mean, and in the canzone Poscia ch’Amor (written circa 1295), where Dante indicts poor management of wealth among the Florentines of his day. In Poscia ch’Amor Dante specifically condemns both those who “throw away their wealth” — “gittar via loro avere” (20) — and those who “hold onto” it: “tenere” (27).

[30] In this early formulation of the binary gittar via versus tenere Dante forecasts the language of the sinners of Inferno 7, who cry out “‘Perché tieni?’ e ‘Perché burli?’” (“Why do you hoard?” and “Why do you squander?” [Inf. 7.30]). “Perché tieni?”, directed at the misers, echoes “tenere” of Poscia ch’Amor, while “Perché burli?”, directed at the prodigals, recalls Poscia ch’Amor’s “gittar via”. The verb tenere appears again with the same meaning in Inferno 7’s opposition “Mal dare e mal tener” (Ill giving and ill keeping [Inf. 7.58]). (On these themes, see the excerpt in Appendix 2 below.)

* * *

[31] For Aristotle in Nicomachean Ethics, sins of excess or uncontrolled desire are classified as sins of “incontinence” (Dante’s “incontenenza” in Inferno 11.82-83). The taxonomy is clear and has been treated as clear in commentaries: everyone notes that in Inferno 11 Dante explicitly places circles 2 to 5 (lust, gluttony, avarice/prodigality, and anger) under the Aristotelian rubric of incontinence. However, the implied philosophy and what it suggests about Dante is less clear. The philosophical implications of defining desire in terms of incontinence have been overlooked in a Dantean critical tradition that has insisted for centuries on the binary of secular versus divine love.

[32] Defining desire in terms of incontinence means that it is not defined dualistically (for the same principle, see the Commento on Inferno 5). The Aristotelian system of virtue as a mean between two sinful extremes is a unitary system, based on a spectrum of behaviors, not a dualistic system like the Christian one.

[33] The Christian system relies on a binary: thus, in Purgatorio, for every capital vice, Dante will produce a corresponding virtue (some more convincing than others). Aristotle’s system instead relies on a spectrum, in which the good is located at the mean, rather than being conceptualized as the opposite of the bad (again, some of the instances are more convincing than others). We need to think more about the productive tensions created by Dante’s deliberate interweaving of the binary Christian system of the vices and virtues with the very different — non-dualistic — Aristotelian system of the golden mean.

[34] Another point worth mentioning is that, in the context of wealth management, Aristotle’s concept of the virtuous mean implies a genuine appreciation of moderate material comfort. In other words, to put this idea into Dante’s own contemporary context: Dante’s use of the Aristotelian template in Inferno 7 distances him from a posture of Franciscan disdain for all material goods.

[35] However, Dante’s thinking about the Church inclines him toward the Franciscan posture, with its strong celebration of poverty as a positive value. And this very canto will indict the avarice of high prelates, popes and cardinals, thus initiating an ongoing critique of ecclesiastical wealth that is of great importance to the Commedia and that it finds its focus in the issue of the Donation of Constantine.

[36] And yet, at the same time, when he has his more secular hat on, Dante is quite capable of appreciating the generosity of those great lords who demonstrate the virtue of liberality in their courts. We can therefore begin to discern in Inferno 7 a fascinatingly complex and nuanced approach toward wealth, which will be a hallmark of Dante’s far from monolithic thinking on this topic:

For a solution to these conflicting viewpoints we might turn to the Monarchia’s positing of “two kinds of nobility, a man’s own nobility and that of his ancestors” (Mon. 2.3.4). But the Monarchia’s neat formula does not capture the complexity and multi-faceted nature of the problem, a complexity that Dante perhaps only fully embraces in the Commedia, where he is capable of valorizing Franciscan poverty and simultaneously making violence against material possessions a sin. The positive evaluation of material goods that is implied by Dante’s infernal taxonomy of violence is another indication of Dante’s adoption of the Aristotelian approach toward wealth management, one that somehow manages to coexist with his Christian idealization of poverty. (“Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia: From the Moral Canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor to Inferno 6 and 7”, 46)

[37] An appreciation of material wealth and the liberality with which it is bestowed can be inferred from the Commedia, from the praise of great feudal lords who show their cortesia by opening their homes and their purses. Thus, the Malaspina family is lauded for their “pregio de la borsa” (the glory of their purse) in Purgatorio 8.129. Moreover, the very existence, in Dante’s hell, of the sins of “violence toward the self in one’s possessions” and “violence toward others in their possessions” (see the circle of violence in Dante’s hell) is significant in this regard: it is not possible to conceptualize the category of violence toward possessions without an implied appreciation of material possessions as a positive good.

[38] The souls of the fourth circle are symmetrically arranged, as befits their equal distance from the virtuous mean. The misers push heavy stones around the circle in one direction, while the prodigals do the same in the other direction. The pilgrim’s interest, however, is not symmetrically distributed. (This move, to establish a symmetry and then to disrupt it, is very Dantean.) He is far more interested in the tonsured souls on his left, and wonders aloud whether they were all clerics: “se tutti fuor cherci” (if all were clerics [Inf. 7.38]).

[39] Virgilio confirms Dante’s suspicion, adding, scandalously, that the souls of the damned misers include popes and cardinals. The Italian words for “pope” and “popes”—“papa” in the singular, “papi” in the plural—has been subliminally anticipated by the repeated “pape” in guardian Plutus’s opening exclamation, adding to the portentousness of this indictment:

Questi fur cherci, che non han coperchio piloso al capo, e papi e cardinali, in cui usa avarizia il suo soperchio. (Inf. 7.46–48)

These to the left—their heads bereft of hair— were clergymen, and popes and cardinals, within whom avarice works its excess.

[40] Dante’s anti-clericalism thus builds steam in Inferno 7. Up to now it has been expressed obliquely, in the inferences embedded in two indirect verses: 1) “colui / che fece per viltà il gran rifiuto” (he who made through cowardice the great refusal) in Inferno 3.59-60 (a possible reference to Pope Celestine V, as discussed in the Commento on Inferno 3), and 2) “con la forza di tal che testé piaggia” (using the power of one who tacks his sails) in Inferno 6.69 (a reference to Pope Boniface VIII).

[41] The question of wealth leads Virgilio into a long explanation, in the second half of Inferno 7 (verses 67-96), on the way in which material goods are distributed to humans by Fortuna. The discussion of Fortuna’s role in distributing material goods is not unconnected to the themes of Inferno 6 and 7. Blind and arbitary in her distribution of wealth, Fortuna reflects Dante’s anxiety about an issue that was roiling Florentine society: as new wealth formed, tensions arose between new magnates and old aristocrats in a rising mercantile world.

[42] These tensions around “new people” and their “new money” explode in Inferno 16, which picks up many of the same themes treated first in Inferno 6 and 7. See the Commento on Inferno 16, “Cortesia and Theory of Wealth”.

[43] In yet another twist in his extraordinarily complex response to classical culture, Dante (through Virgilio) refutes the classical understanding of the goddess Fortuna, which holds that she is blind and therefore arbitrary and capricious in her distribution of material goods, randomly causing some human fortunes to rise and others to fall. Instead, he insists (in a theologically inaccurate way that will not be picked up in Paradiso) that Fortuna is a minister of God, positioned in heaven with the other deities.

[44] In effect, Dante de-classicizes and Christianizes the classical goddess. Dante’s move to Christianize classical Fortuna might be, as suggested above, a way of defusing the social anxiety and envy that was a primary feature of Florentine life. As a homeless and stateless exile, Dante had even more reason to fear the capriciousness of Fortuna. If instead he conceives Fortuna to be a minister of divine Providence, her actions are by definition not capricious and therefore less threatening. Although we cannot understand or appreciate her actions, they are willed by Providence and therefore must be seen as part of a larger divine plan, which in turn must be construed as good.

[45] For the first time in Inferno, the poet disrupts the neat symmetry between the formal container—the canto—and the circle of hell that the canto describes. In other words, for the first time, the end of this canto, Inferno 7, does not correspond to the end of an infernal circle. I mention this because the one-to-one alignment that Dante creates serves, in my view, as a pedagogical tool: “The practice of strict alignment adopted for the first six canti is a teaching strategy, in that it allows readers (along with “Dante”, the protagonist) to grasp more readily the contours of the new world to which they are being introduced. These contours become more fluid, more narratologically interesting, and more difficult to keep in mind, as readers leave the circle of avarice and prodigality and enter the circle of anger” (“Dante, Teacher of his Reader”, 37, in Coordinated Reading).

[46] Virgilio announces the departure of the travelers from the fourth circle in verse 97, with 33 verses of Inferno 7 still to go. He declares that they now descend toward “maggior pièta” (greater suffering [97]), and eventually, in verse 106, the travelers reach a swamp that has the name Styx: “In la palude va c’ha nome Stige” (In the swamp that has the name Styx [Inf. 7.106]). This is the fifth circle, referred to as the circle of anger, but likely also containing the slothful, for the travelers see souls, “genti fangose” (muddy folk [110]) immersed in Styx. These souls, “stuck in the mud” (“Fitti nel limo” [121]), describe themselves as “tristi” — sad, downcast, depressed — and speak of carrying within themselves an “accidioso fummo” (the dark smoke of sloth [123]). This is the black smoke of acedia:

Tristi fummo ne l’aere dolce che dal sol s’allegra, portando dentro accidioso fummo. (Inf. 7.121-23)

We were sad in the sweet air that’s gladdened by the sun, carrying within the dark smoke of sloth.

[47] The adjective “accidioso” in verse 122 is formed from Italian “accidia”, sloth, which in turn derives from the Latin acedia, one of the seven deadly vices. Acedia and tristitia are related; Aquinas gives as his definition of acedia: “Acedia… est quaedam tristitia, qua homo redditur tardus ad spirituales actus propter corporalem laborem” (Sloth is a kind of sadness, whereby a man becomes sluggish in spiritual exercises because they weary the body [ST 1.63.2.ad2]).

[48] The souls who declare “Tristi fummo” (We were sad [Inf. 7.121]) are in the Styx and therefore must be considered in tandem with the souls of the wrathful who also inhabit the Styx (although not fully immersed), whom we meet in the next canto. When the melancholic souls at the end of canto 7 are considered together with the wrathful souls of canto 8, it is possible to infer the lineaments of a Dantean version of a second Aristotelian vice/virtue spectrum, this time with respect to anger rather than with respect to wealth.

[49] Aristotle constructs an anger spectrum on which irascibility and lack of spirit are extremes while good temper is the virtuous mid-point. According to my theory, Dante suggests the outline of an anger spectrum in which righteous anger is the virtuous mean, flanked by the vicious extremes of melancholic tristitia and rabid ira. The melancholics whose black bile billows inside them are found at the end of Inferno 7, while the virtuous mean is performed by the pilgrim in his righteous anger toward Filippo Argenti, the wrathful soul who assaults him in Inferno 8. The paradigm that results is as follows:

melancholic tristitia ⇤⇤⇤⇤ righteous anger ⇥⇥⇥⇥ rabid wrath

Appendix 1

Cecco d’Ascoli Accuses Dante of Determinism: A Note on Inferno 7, verse 89

(A detailed exposition of this analysis may be found in my essay “Contemporaries Who Found Heterodoxy in Dante: Cecco d’Ascoli, Boccaccio, and Benvenuto da Imola on Fortuna and Inferno 7.89,” cited in Coordinated Reading)

[50] The philosophical layers that can be uncovered in the Commedia are well displayed by the complexities that surround verse 89 of Inferno 7: “necessità la fa esser veloce” (necessity makes her [Fortuna] swift). The astrologer and medical doctor Cecco d’Ascoli (1257-1327) inveighed against this verse in his philosophical poem Acerba.

[51] Cecco attacks Dante for belief in determinism, in other words for insufficient attachment to the idea of free will. Not only does it rarely occur to us that Dante might have been considered a determinist by some of his contemporaries, we certainly do not associate this issue with Inferno 7.

[52] In the capitolo “Della Fortuna” of Acerba, Cecco d’Ascoli openly censures Dante for “sinning” in his linkage of Fortuna with “necessità” (a code word for determinism). He explicitly accuses Dante of not sufficiently championing free will:

Non fa necessità ciascuno movendo, Ma ben dispone creatura umana Per qualità, cui l’anima, seguendo L’arbitrïo, abbandona e fassi E serva e ladra e, di virtute estrana, Da sé dispoglia l’abito gentile. In ciò peccasti, fiorentin poeta, Ponendo che li ben della fortuna Necessitati sieno con lor meta. Non è fortuna cui ragion non vinca. Or pensa, Dante, se prova nessuna Si può più fare che questa convinca. Fortuna non è altro che disposto Del cielo che dispon cosa animata Qual, disponendo, si trova all’opposto. Non vien necessitato il ben felice. Essendo in libertà l’alma creata, Fortuna in lei non può, che contraddice. (Acerba, 2.1.719-736. Cited in the edition of Achille Crespi, orig. 1927, rpt. Milano: La Vita Felice, 2011; italics mine)

Each heaven does not determine the soul by necessity as it moves, but only impresses a certain disposition on the human creature. The soul, following its free will, abandons its heavenly disposition and makes itself vile, a slave and thief, estranged from virtue; it strips itself of its noble habits. In this you sinned, Florentine poet, positing that the goods of fortune are assigned by necessity. There is no fortune that reason does not conquer. Think now, Dante if there is a proof that can be adduced more convincing than this one. Fortune is nothing but the disposition of the heavens that dispose the living thing, which then changes to its opposite (from passive to active). Happiness is not brought about by necessity. The soul having been created in liberty, fortune has no power over it that could contradict its will. (Translation mine)

[53] Cecco here accuses Dante of according too much influence to astral determinism (“necessità”). His attack on Dante was noted by contemporaries, and it is important for us to note that they did not dismiss it out of hand. Boccaccio in his Esposizioni writes that the words of Inferno 7.89, if not well understood, could generate “error” (Esposizioni, Canto VII, Esposizione litterale, § 73).

[54] Benvenuto da Imola explicitly refers to a contemporary debate provoked by “necessità la fa esser veloce” (Inf. 7.89). He writes that many had much to say on the subject, that there were those who defended Dante and those who attacked him, and he invokes Cecco d’Ascoli by name in the latter category:

Et hic nota lector quod circa literam istam est toto animo insistendum, quia istud dictum non videtur bene sanum; ideo multi multa dixerunt, alii pro autore, alii contra autorem, sicut Cechus de Esculo qui satis improvide damnat dictum autoris exclamans: In ciò fallasti [sic: Cecco wrote peccasti] fiorentin poeta. (Benevenuti de Rambaldis de Imola, Comentum super Dantis Aldigherij Comoediam, ed. J. P. Lacaita, Firenze: Barbèra, 1887)

And here, reader, note that about this passage one must insist with all one’s spirit, for this word might seem to be not quite sound. Therefore many have said many things, some on behalf of the author, others against the author, like Cecco d’Ascoli who quite recklessly condemns the author’s word exclaiming: In ciò fallasti [sic] fiorentin poeta. (Translation mine)

[55] Benvenuto refutes Cecco d’Ascoli and champions Dante by pointing to the passage in Purgatorio 16 in which Dante explicitly states that humans have reason and free will and that free will trumps the movements of the heavens and astral determinism:

Sed parcat mihi reverentia sua, si fuisset tam bonus poeta ut astrologus erat, non invexisset ita temere contra autorem. Debebat enim imaginari quod autor non contradixisset expresse sibi ipsi, qui dicit Purgatorii cap. XVI: El cielo i vostri movimenti initia, Non dico tutti, ma posto ch’io ’l dica, Dato v’è lume a bene et a malitia.

But may his reverence spare me, if he were as good a poet as he was an astrologer, he would not have inveighed so boldly against the author. For he ought to imagine that the author clearly did not contradict himself, who says in chapter XVI of Purgatorio: The heavens initiate your movements; I don’t say all of them, but, were I to say it, you have been given light to discern good and evil.

[56] The controversy that I have briefly related here offers us an opportunity to see that Dante’s contemporaries were capable of finding challenges in Dante’s text that we no longer see. All trace of the contemporary response to Inferno 7.89 is missing from today’s commentaries; indeed, one has to read Acerba to learn that it ever happened. After I read Acerba I looked through the contemporary commentaries and was astounded to find Benvenuto responding to Cecco d’Ascoli by name. After reading Acerba the importance of Benvenuto’s and Boccaccio’s testimony becomes evident: while Cecco may seem like a marginal figure, Boccaccio and Benvenuto are not, and yet they took Cecco’s accusation with utmost seriousness. If only we had a record of the “many” other thinkers who, according to Benvenuto (“multi multa dixerunt”), debated Inferno 7.89!

For more on the controversy generated by Inferno 7.89, see my essay “Contemporaries Who Found Heterodoxy in Dante: Cecco d’Ascoli, Boccaccio, and Benvenuto da Imola on Fortuna and Inferno 7.89, in Coordinated Reading. For more on points of contact between Cecco d’Ascoli and Dante in this commentary, see the Commento on Inferno 20, which raises issues of determinism and astrology vis-à-vis the bolgia of the false prophets, and the Commento on Purgatorio 16.

Appendix 2

On Dante’s canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’ Amor in Inferno 7

(Excerpt from: “Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia: From the Moral Canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor through Convivio to Inferno 6 and 7”)

[57] The Aristotelian system that supports the two contrary sins of Inferno 7 is that of Le dolci rime, while the language that characterizes Inferno 7’s two groups of sinners is derived from Poscia ch’Amor. Dante treats various types of non-virtuous behavior (later classified as sins of incontinence) in Poscia ch’Amor, referring to “lussuria” and, colorfully, to “divorar cibo” (Poscia ch’Amor, 33). But he begins, as we see in stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor below, by tackling wealth (“avere” in verse 20) and its proper deployment in society:

Sono che per gittar via loro avere credon potere capere là dove li boni stanno che dopo morte fanno riparo nella mente a quei cotanti c’hanno conoscenza. Ma lor messione a’ bon’ non può piacere, perché tenere savere fôra, e fuggirieno il danno che s’agiugne a lo ’nganno di loro e della gente c’hanno falso giudicio in lor sentenza. Qual non dirà fallenza divorar cibo ed a lussuria intendere, ornarsi come vendere si dovesse al mercato d’i non saggi? ché ’l saggio non pregia om per vestimenta, ch’altrui sono ornamenta, ma pregia il senno e li gentil coraggi. (Poscia ch’Amor, 20-38)

There are those who think that to dissipate their wealth is the way to win a place with the worthy who after death continue to dwell in the minds of such as are wise. But their extravagance cannot meet with good men's approval; so that they would be wiser to keep their cash and thus avoid also the loss which is added to their illusion — theirs and that of those whose opinion of them shows false judgement. Who will not call it folly to guzzle and give oneself over to lechery? To deck oneself out as though one were up for sale at Vanity Fair? For the wise do not esteem a man for his clothes, which are outward adornments, but for intelligence and nobility of heart. (Foster-Boyde translation)

[58] Wealth management is characterized in the above stanza in terms of its Aristotelian extremes. Those who “throw away their wealth” (verse 20: “gittar via loro avere”) will be the prodigals of Inferno 7, while those lower down in the stanza, who “hold onto” their wealth (verse 27: “tenere”), will be the misers of Inferno 7. In the canzone Dante anticipates the language of the sinners of Inferno 7, who cry out “‘Perché tieni ?’ e ‘Perché burli?’” (Inf. 7.30): “Perché tieni?”, directed at the misers, echoes “tenere” of Poscia ch’Amor, while “Perché burli?”, directed at the prodigals, recalls Poscia ch’Amor’s “gittar via”. The verb tenere appears again with the same meaning in Inferno 7’s opposition “Mal dare e mal tener” (Inf. 7.58).

[59] The reading that holds that Dante creates an opposition between gittar via and tenere in stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor, anticipating the opposition “Mal dare e mal tener” of Inferno 7, was put forward by Barbi-Pernicone but is by no means universally accepted. I strongly support the Barbi-Pernicone reading. In my view, stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor follows through in applying to social life the Aristotelian template already laid down in Le dolci rime. If we accept gittar via and tenere as the two Aristotelian extremes of vice in the context of wealth management, we can construe verses 26-31, with Barbi-Pernicone, thus:

Ma le spese dei prodighi non possono piacere ai buoni, cioè ai virtuosi, alla gente di valore, perché altrimenti bisognerebbe considerare cosa saggia (savere fora), cioè azione virtuosa, anche l’eccesso opposto di serbar denaro (tenere), come fanno gli avari, e non sarebbe danno, come in realtà lo è, quello che a loro deriva dall’esser prodighi, dal comportarsi, cioè, non secondo virtù. (Rime della maturità e dell’esilio, eds. Michele Barbi and Vincenzo Pernicone, Firenze, Le Monnier, 1969, p. 441)

[60] The virtue not embraced in stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor is the virtue of liberality, as Piero Cudini convincingly explains in his gloss of tenere:

serbare rigorosamente il proprio denaro, essere avaro; che questa sia l’accezione in cui viene qui usato il verbo sembra dimostrato anche dal suo uso nel canto degli avari e dei prodighi [. . .] sembra abbastanza chiara l’opposizione / analogia tra ‘gittar via’ (v. 20) e ‘tenere’ come peccati entrambi da evitare, e che comunque nulla hanno in comune con la ‘medietà’ propria della leggiadria. (Le Rime, ed. Piero Cudini, Milano, Garzanti, 1979, p. 137)

[61] De Robertis on the other hand speaks for those who claim that tenere in verse 27 is intended in a positive sense, writing that to see an Aristotelian scheme at work here is to attribute to Dante an excess of subtlety. For him, this canzone does not treat virtue but practical wisdom : “Qui non si tratta di ‘virtù’, ma della risposta della saggezza pratica” (Rime, edizione commentata a cura di Domenico De Robertis, Firenze, Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2005, p. 147). However, Poscia ch’Amor is a canzone in which the Aristotelian framework of the virtuous mean is already a given. Its “saggezza pratica” lies precisely in unpacking the behavioral implications of the Aristotelian framework already accepted and carried over from Le dolci rime.

[62] There is, moreover, a compelling internal proof of the correctness of the Barbi-Pernicone reading of stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor. This internal proof is in stanza 7, where Dante defines the man who possesses leggiadria in terms of his perfect ability to give and to receive, his perfect practice of liberality: “Dona e riceve l’om cui questa vole / mai non se ·n dole” (Poscia ch’Amor, 115-116). And in fact De Robertis offers for these verses the gloss “esercitando la virtù della liberalità” (ed. comm., p. 155), thus accepting an Aristotelian reading of stanza 7 that he had rejected as excessive in stanza 2.

[63] The cavaliere who possesses leggiadria in Poscia ch’Amor gives and receives without erring. He experiences no confusion in mediating between Christian vice and courtly virtue, no difficulty in distinguishing between the vice of prodigality and the virtue of liberality. For such a man, donare and ricevere are in perfect equilibrium. He gives and he receives in exactly the right measure. He never suffers as a result of such decisions: “mai non se ·n dole” (Poscia ch’Amor, 116). Never for such a man the wrong size tip! Never hurt feelings about an insufficient gift! This leggiadro cavaliere is someone who always acts correctly in the agora of human exchange, which is never for him the “mercato d’i non saggi” (Poscia ch’Amor, 35).

[64] In the beautiful synthesis of liberality that opens stanza 7 of Poscia ch’Amor, “Dona e riceve”, Dante goes back to the Aristotelian mean of stanza 2, where the mean is evoked in malo, and he rephrases it in bono: donare and ricevere in stanza 7 are positive antonyms that replace stanza 2’s negative antonyms gittar via and tenere. The behavior extolled in “Dona e riceve l’om cui questa vole” is also the perfect inverse of Inferno 7’s “Mal dare e mal tener” (Inf. 7.58).

Return to top

Return to top