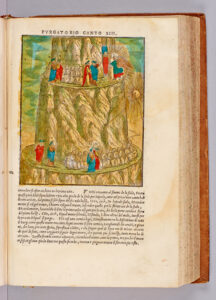

Purgatorio 13 begins with the arrival at the second terrace: “dove secondamente si risega” (where for a second time the mountain is indented [Purg. 13.2]). Here we see another reminder that the job of the mountain of Purgatory is to perform a kind of aggressive cognitive behavioral therapy, with the goal of dishabituating us from vice, the inclination toward sin.

In the exordium of Purgatorio 13 we learn that this is the mountain that “dis-evils” us (verse 3), or “unsins us” in the Hollander translation. In other words, Mount Purgatory dishabituates those who climb it from evil:

Noi eravamo al sommo de la scala, dove secondamente si risega lo monte che salendo altrui dismala. (Purg. 13.1-3)

We now had reached the summit of the stairs where once again the mountain whose ascent delivers man from sin has been indented.

Dante’s coinage “dismala” is a verb formed from the privative prefix dis + verb malare, based on the noun male, evil, and therefore with the sense that the mountain “dis-evils” us or purifies us from vice. It recalls a previous coinage formed with the prefix dis + verb, also in the context of defining the work of purgation: “disusa” in the exordium of Purgatorio 10, formed from dis + verb usare. Here the gate of Purgatory is that which “’l mal amor de l’anime disusa” (the evil love of the souls dishabituates us from using [Purg. 10.2]).

Both definitional moments share a verb formed on the privative prefix dis (“disusa”, “dismala”), reminding us that the work of Purgatory is to remove from our selves that which is not suitable for Paradise. In the Purgatorio 13 passage we do not find any form of “amore” — love — although the new coinage “dismala” recalls the “malo amor” of Purgatorio 10.

These coinages look forward to the critical discussion in Purgatorio 17 where Virgilio explains to his charge that all human behavior — both good and evil — is rooted in love: love that inclines toward the good, or love that inclines toward the bad (“malo amor”). Augustine provides the language of bonus amor versus malus amor. In City of God 14.7 he writes that “a right will is good love and a wrong will is bad love” (“recta itaque voluntas est bonus amor et voluntas perversa malus amor”). Augustinian bonus amor versus malus amor underwrites Dante’s characterization of the entrance to Purgatory as ‘‘la porta / che ’l mal amor de l’anime disusa” (Purg. 10.2). Further discussion may be found in “Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

As discussed in the Commenti on Purgatorio 10-12, the canti of the terrace of pride, a governing narrative template is imposed on each of the seven terraces of Purgatory. On each terrace we will find the following narrative building blocks: examples of the virtue that corresponds to the vice being purged (of which the first is always taken from the life of Mary), encounters with souls, examples of the vice being purged, the pardon executed by the angel, and the recitation of a Beatitude upon departure.

Within this template, Dante demonstrates great variatio, for instance in coming up with different media for the performance of the examples. On the terrace of pride the examples are engraved in stone, a visual medium, whereas on the terrace of envy Dante will have recourse to an aural medium for the exempla: sound bites take over the terrace’s airwaves, as disembodied spirits call out a kind of anti-envy rap, always in direct discourse.

The sound bites are all examples of love, based on the idea that caritas (love) is the virtue that is the opposite of envy. Yet the correspondence is not so clear-cut as it might seem, and merits greater atttention from the commentary tradition.

The choice of “amore” as the virtue corresponding to the vice of envy suggests some strain in Dante’s conceptual scheme, given the foundational importance of love as the basis for all human behavior (see the Commento on Purgatorio 17) How can “amore” be the specific virtue opposed to the vice of envy, when, as Virgilio will explain in Purgatorio 17, every single vice is itself a deformation of “amore”?

By the same token, each of the virtues, not just the virtue corresponding to envy, but the others as well (humility, gentleness, liberality, and so forth) might be seen as inflections of “amore”. The borrowing of the large category “love”, which holds all the virtues, as the specific virtue that corresponds to a specific vice, betrays some instability in the scheme. More work needs to be done on the ethical paradigms that Dante is using and how he may have modified them in ways that are at times idiosyncratic and perhaps not fully under his control.

Conversely, one could claim that the insertion of love so prominently into his ethical scheme now, in Purgatorio 13, is precisely what Dante wants to achieve. In this way, he is already beginning the build-up to the revelation, in Purgatorio 17, that all human conduct is rooted in love.

The spirits in Purgatorio 13 shout out exemples of caritas, which are described as “courteous invitations to love’s table” :

e verso noi volar furon sentiti, non però visti, spiriti parlando a la mensa d’amor cortesi inviti. (Purg. 13.25-27)

we heard spirits as they flew toward us, though they could not be seen—spirits pronouncing courteous invitations to love's table.

These “courteous invitations to love’s table” come, first, from the life of Mary, and then from classical and biblical sources. The first voice that Dante hears calls out the words spoken by Mary at the wedding of Cana to indicate that the guests are lacking wine. The voice flies by, loudly reiterating its sound bite as it distances itself:

La prima voce che passò volando ‘Vinum non habent’ altamente disse, e dietro a noi l’andò reiterando. (Purg. 13.28-30)

The first voice that flew by called out aloud: “Vinum non habent,” and behind us that same voice reiterated its example.

The classical example is that of Orestes, who announces his identity so that his best friend Pylades cannot sacrifice himself in his place. This example of true friendship between men, known to Dante from Cicero’s De amicitia, is interesting also in the context of the Titus and Gisippus story in the Decameron (10.8).

The biblical example is anomalous in that it does not feature a particular person or event; rather, this is Jesus’ exhortation in his Sermon on the Mount to “Love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44). Again, we see how a hugely important concept, that of of loving one’s enemies, a concept that is foundational to Christianity, is yoked into the terrace of envy. On the one hand, it almost seems out of place and disproportionate, as discussed above.

On the other hand, as I suggested above, the use as an example of envy of a foundational Christian concept opens the door to a much broader meditation with respect to envy and vice in general. The example/sound bite “Amate da cui male aveste” (“Love those by whom you have been hurt” [Purg. 14.36]) comes from no less a text than Christ’s Sermon on the Mount:

43 You have heard that it was said, “Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” 44 But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, 45 that you may be children of your Father in heaven (Matthew 5:43-45)

Here we see how the discourse on the terrace of envy broadens into a profound meditation on the relationship of the self and the other.

The use of direct discourse in these examples — “Vinum non habent” (Purg. 13.29), “I’ sono Oreste” (Purg. 13.32), and “Amate da cui male aveste” (Purg. 13.36) — gives a role-playing and performance value to each utterance: these words are theatrically performed by the voices, whose origins we never see. The lack of a visual source will be connected to the gruesome form of punishment exacted from the souls who purge envy on this terrace.

Purgatorio 13 is the first of two and one-third canti devoted to the terrace of envy; the rest of this canto introduces us to the souls and their punishment. The torment inflicted on the envious is particularly gruesome, and is borrowed from the practice of falconry: their eyes are sewn shut with wire, to prevent them from seeing and envying the good fortune of others.

Again, we see that the thread that runs through this analysis is the relationship of self to other.

Dante asks whether any of the blinded souls is Italian and consequently strikes up a conversation with a Sienese lady, Sapìa, the aunt of Provenzan Salvani (whom we met in Purgatorio 11). She rejects his characterization of her as “Italian” however, beginning her reply with a typically purgatorial refusal to embrace the earthly values that yet still mean so much to these souls:

O frate mio, ciascuna è cittadina d’una vera città; ma tu vuo’ dire che vivesse in Italia peregrina. (Purg. 13.94-96)

My brother, each of us is citizen of one true city: what you meant to say was “one who lived in Italy as pilgrim.”

Sapìa’s continued attachment to her earthly self is apparent in her animated account of how she rejoiced in the defeat of her fellow Sienese at the hands of the Florentines at the battle of Colle di Val d’Elsa (8 June 1269). Her nephew Provenzan Salvani led the Sienese troops and was killed in this battle. At witnessing the rout of the Sienese, Sapìa was so overcome by happiness that she raised her face to heaven and called out to God “Omai più non ti temo!” (Now I fear you no more! [Purg. 13.122]). In other words, she has experienced such extremes of joy that now she fears nothing else that can happen to her.

Dante here teases out the implications of envy with respect to the self’s relation to the other. Beginning with envy as the desire for what others have, Dante moves in the case of Sapìa to envy as extreme joy at witnessing what others lose. As though taking a cue from the framework regarding the self and others, Dante-pilgrim distances himself from the envious souls. In reply to Sapìa’s question about his own identity, he acknowledges being alive but claims that he has little fear of spending future time on the terrace of envy. Rather, he almost boasts, his concern is focused on the terrace of pride:

«Li occhi», diss’io, «mi fieno ancor qui tolti, ma picciol tempo, ché poca è l’offesa fatta per esser con invidia vòlti. Troppa è più la paura ond’è sospesa l’anima mia del tormento di sotto, che già lo ’ncarco di là giù mi pesa». (Purg. 13.133-38)

“My eyes,” I said, “will be denied me here, but only briefly; the offense of envy was not committed often by their gaze. I fear much more the punishment below; my soul is anxious, in suspense; already I feel the heavy weights of the first terrace.”

Envy is such a déclassé vice compared to pride!

Return to top

Return to top