The heaven of Mars is a long heaven, comprising the last third of Paradiso 14, and then Paradiso 15, 16, 17, and the first half of canto 18. The transition to Jupiter occurs in Paradiso 18.61-62.

The heaven of Mars is roughly one canto less in overall length than the heaven of the sun. The heaven of the sun includes four complete canti, Paradiso 10-13, plus about two-thirds of a fifth canto, Paradiso 14. The heaven of Mars includes three complete canti, Paradiso 15-17, plus about one-third of canto 14 and a bit less than one-half of canto 18.

Although it has crusading and Church militant elements, the heaven of Mars is ultimately the heaven of personal affect and personal history. The Augustinian section at the beginning of Paradiso 15, with its emphasis on right love versus wrong love — “l’amor che drittamente spira” (the love that breathes righteousness [2]) versus “cupidità” (greed) in verse 3 — reprises the essence of Beatrice’s Augustinian critique in Purgatorio 30-31 and sets the stage for the affective complexity of this heaven.

The paradoxical currents circulating around affect in the heaven of Mars are built into the long prefatory meditation on right versus wrong love, which concludes with a condemnation of one who, “on account of love of things that do not last” — “per amor di cosa che non duri” (11) — deprives himself of the love that lasts eternally. And yet . . . this heaven is chock-full of the love of things that do not last.

The personal nature of this heaven is immediately on display. Looking at Beatrice, Dante feels that he has reached the extreme “of my glory and of my paradise”:

ché dentro a li occhi suoi ardeva un riso tal, ch’io pensai co’ miei toccar lo fondo de la mia gloria e del mio paradiso. (Par. 15.34-36)

for in the smile that glowed within her eyes, I thought that I—with mine—had touched the height of both my blessedness and paradise.

The heaven of Mars is anticipated by the discussion of the resurrected body in the first part of Paradiso 14 (still in the heaven of the sun), a discussion that leads the souls to exclaim “Amen” in joy at the thought that they will get their bodies back. In fact, they experience “disio de’ corpi morti” (Par. 14.63), and their desire for their dead bodies is conditioned by their desire “for their mothers, fathers, and for others dear to them before they were eternal flames”:

forse non pur per lor, ma per le mamme, per li padri e per li altri che fuor cari anzi che fosser sempiterne fiamme. (Par. 14.64-66)

not only for themselves, perhaps, but for their mothers, fathers, and for others dear to them before they were eternal flames.

The mothers and fathers desired by the souls of Paradiso 14.64-65 are historicized in the heaven of Mars, where they are the mothers and fathers of Florence, and where Dante meets his own great-great-grandfather.

Dante’s paternal ancestor, Cacciaguida (we learn in Par. 16.34-39 that he was born in 1091), is described in a simile where his affection is compared to that of Anchises, father of Aeneas, on greeting his son:

Sì pia l’ombra d’Anchise si porse, se fede merta nostra maggior musa, quando in Eliso del figlio s’accorse. (Par. 15.25-27)

With such affection did Anchises' shade reach out (if we may trust our greatest muse) when in Elysium he saw his son.

We note the stipulation of verse 26: “if we may trust our greatest muse” refers to the description offered by Vergil of the affectionate encounter between Anchises and Aeneas in Book 6 of the Aeneid. This verse constitutes the first, albeit indirect, reference to Vergil in the poem since the disappearance of Virgilio in Purgatorio 30. In Purgatorio 30, in recounting the moment of his loss, Dante refers to the Latin poet as “Virgilio dolcissimo patre” (Virgilio sweetest father [Purg.30.50]). Thus, true to the dialectical terza-rima texture of this poem, ever spiraling forward and back, the arrival of a new father, Cacciaguida, elicits from Dante the memory of the father whom he has lost, now remembered as “nostra maggior musa”: our greatest poet.

The heaven of Mars is the heaven of the bloodline: of lineage, of ancestry, of family — root, branch, and tree. Cacciaguida’s first words to Dante are “o sanguis meus” — “O blood of mine” (Par. 15.28) — and canto 16 begins with Dante’s celebration of his family lineage, his personal and individual “nobility of blood”: “nobiltà di sangue” (Par. 16.1).

Cacciaguida explains Dante’s family to him, explaining where he fits into the family lineage and the origin of his family name, “Alighieri”. The concept of a family name is of such importance that it is here referenced twice: Cacciaguida tells Dante that “tua cognazione” (your family name [92]) comes to him from Cacciaguida’s son, Alighiero I, and later adds that the family’s “sopranome” (surname [138]) originally derives from Cacciaguida’s wife’s non-Tuscan family in “val di Pado” (valley of the Po [137]).

Most of all, Cacciaguida explains who he, Cacciaguida, is in relation to the pilgrim:

Poscia mi disse: «Quel da cui si dice tua cognazione e che cent’anni e piùe girato ha ’l monte in la prima cornice, mio figlio fu e tuo bisavol fue: ben si convien che la lunga fatica tu li raccorci con l’opere tue.» (Par. 15.91-96)

then said: “The man who gave your family its name, who for a century and more has circled the first ledge of Purgatory, was son to me and was your great-grandfather; it is indeed appropriate for you to shorten his long toil with your good works.”

The above verses showcase Dante’s genial method of buttressing important moments by using the fictional truth of the text itself, supporting textual reality with more textual reality. Here Cacciaguida tells the pilgrim that his son, Alighiero I, Dante’s great-great-grandfather, is still circling the first ledge of Purgatory, the terrace of pride. Cacciaguida thus lets his descendant know that pride is a family trait: we remember the pilgrim’s stated fear (in Purgatorio 14) that he will be spending much time on the terrace of pride when he returns to Purgatory.

This fascinating confirmation of pride as an Alighieri family vice thus enters the Commedia’s long and complex meditation on what humans can inherit and how they are influenced by outside forces, like the stars.

A lot of affect enters the Paradiso when we enter the heaven of Mars. We are plunged into a world of human feeling and human history: when Dante meets his ancestor Cacciaguida, the conversation becomes very personal, both about Dante’s family and about Florence. Florence is Dante’s birthplace, the place in which he came of age as an author, married, had children, and entered politics. Florence is the home from which he was wrongly exiled. Not for nothing does Florence elicit great passion from our poet throughout the Commedia.

This is a social heaven, a heaven that features culture in all its social manifestations, as the previous heaven featured ideas. The heaven of Mars depicts family life, civic life, social status, and the use of language. Language is prioritized as perhaps the greatest of cultural artifacts.

Dante shows us language in family life (mothers telling stories to children of Troy, Fiesole, and Rome), as well as the use of language to communicate social status. He raises the issues of knighthood and other social privileges, fashion and clothing for both men and women, dowries, the position and tasks of women, inheritance, the origin of one’s family name (Dante’s family name comes through his mother’s line), sport (the reference to the palio in Paradiso 16.42), food. The heaven of Mars is about the self in connection to the ties that bind.

The essence of the personal is captured in the way that Cacciaguida speaks to his descendant in verses 58-60, where he lets Dante know that he is right to wonder who Cacciaguida is, right to focus on Cacciaguida as a specific individual, and equally right to note that Cacciaguida seems more happy to meet Dante than any other soul in this heaven. Using the conceit that Dante does not articulate his questions because he knows that the souls in heaven know what he wants to know, Cacciaguidsa says: “e però ch’io mi sia e perch’ io paia / più gaudïoso a te, non mi domandi, / che alcun altro in questa turba gaia (you do not ask me who I am / and why I seem more joyous to you than / all other spirits in this festive throng [Par. 15.58-60]).

Eventually, in the heaven of the contemplatives, Peter Damian will tell the pilgrim that it does not matter who he; nor does it matter which particular soul in the seventh heaven speaks with Dante. In this divergence of approaches is the key of the heaven of Mars as Dante conceives it: in the heaven of Mars, the personal is permitted, it is indeed valorized.

The heaven of Mars is designated to capture all the affect that humans have directed toward Paradise in their thinking about the home of the blessed. Augustine as Bishop of Hippo received letters from people who wanted and expected to meet their beloveds in Paradise. It is this human need — this human affect — that Dante funnels and directs toward his heaven of Mars.

In Paradiso 15 Cacciaguida paints for his descendant the picture of the idyllic Florence of old in which he, Cacciaguida, lived, before Florentine society was overtaken by decay and corruption. Dante’s description of an earlier Florence is full of real history, and at the same time it is an idealized vision of the city when it was pure and at peace:

Fiorenza dentro da la cerchia antica, ond'ella toglie ancora e terza e nona, si stava in pace, sobria e pudica. (Par. 15.97-99)

Florence, within her ancient ring of walls— that ring from which she still draws tierce and nones— sober and chaste, lived in tranquility.

In the above passage, Cacciaguida’s “Fiorenza” is sober and chaste: “sobria e pudica” (99). Gendering the city female in this way, and conferring upon female Fiorenza the female virtues of soberness and chastity, conveyed through the feminine adjectives “sobria e pudica”, Dante reflects the importance of female virtue as a measure of honor.

In a patrilineal and honor-based culture like that of Dante’s Florence, the honor of the society is measured by the comportment of its women. The regulation of women’s behavior is, therefore, a critical piece of the social fabric. The chastity and sobriety of Cacciaguida’s “Fiorenza” contrasts with the current sordid scene, where a daughter’s birth brings fear to her father, and where all facets of female behavior are unregulated. In Cacciaguida’s time, the ages and dowries of women were not yet without misura: “’l tempo e la dote / non fuggien quinci e quindi la misura” (age and dowry did not flee the proper measure [Par. 15.105]).

We remember the importance of the word misura as a social barometer from a previous discussion of Florentine corruption, in Inferno 16. In contemporary Florence, there is no misura in female dress, and there is no misura in female dowry requirements, which bankrupt contemporary Florentine fathers. By contrast, in Cacciaguida’s time, there were not yet expensive ornamentation and misura still held sway:

Non avea catenella, non corona, non gonne contigiate, non cintura che fosse a veder più che la persona. Non faceva, nascendo, ancor paura la figlia al padre, che ’l tempo e la dote non fuggien quinci e quindi la misura. (Par. 15.100-05)

No necklace and no coronal were there, and no embroidered gowns; there was no girdle that caught the eye more than the one who wore it. No daughter’s birth brought fear unto her father, for age and dowry then did not imbalance— to this side and to that—the proper measure.

The war in which Dante’s ancestor Cacciaguida participated was not with his fellow citizens in the kind of factional strife that plagued Florence in Dante’s lifetime (and that caused him to be exiled from Florence). From Dante’s perspective, Cacciaguida fought in an honorable cause and acquitted himself well: he became a knight under the emperor Conrad III, and was killed in the Second Crusade. Thus, Cacciaguida was a crusader, and the end of Paradiso 15 offers the most conventional medieval Christian anti-Muslim rhetoric that you will find in the Commedia.

***

Chapter 10 of The Undivine Comedy, “The Sacred Poem Is Forced to Jump: Closure and the Poetics of Enjambment,” analyzes the latter half of Paradiso from a meta-narrative perspective. Paradiso 15 offers a foundational passage in this regard, verses that provide a philosophical key to reading Paradiso. In answer to Cacciaguida’s exhortation to Dante that he sound forth his will and his desire (in other words, Cacciaguida’s exhortation to Dante to articulate what he wants to know, to speak in language), Dante replies by explaining the diegetic problems — problems of dis-equality and difference — that beset all mortals:

Poi cominciai così: «L'affetto e ’l senno, come la prima equalità v’apparse, d’un peso per ciascun di voi si fenno, però che ’l sol che v’allumò e arse, col caldo e con la luce è sì iguali, che tutte simiglianze sono scarse. Ma voglia e argomento ne’ mortali, per la cagion ch’a voi è manifesta, diversamente son pennuti in ali; ond’io, che son mortal, mi sento in questa disagguaglianza, e però non ringrazio se non col core a la paterna festa. (Par. 15.73-84)

Then I began: “As soon as you beheld the First Equality, both intellect and love weighed equally for each of you, because the Sun that brought you light and heat possesses heat and light so equally that no thing matches His equality; whereas in mortals, word and sentiment— to you, the cause of this is evident— are wings whose featherings are disparate. I—mortal—feel this inequality; thus, it is only with my heart that I can offer thanks for your paternal greeting.

As I write in The Undivine Comedy:

The pilgrim cannot express his thanks because he is mortal and, being mortal, a creature of difference; never (in a typically Dantesque move) have the disadvantages of mortality been more stunningly expressed than in the simplicity of “ond’io, che son mortal” followed by the enjambment that isolates and highlights the word that forms a hemistich, the magnificently protracted “disagguaglianza”. (p. 219)

This passage sets us a clear binary between humans and God: humans are mortal and are characterized by dis-equality, “disagguaglianza” (Par. 15.83). In sharp contrast, God/Paradise/Transcendence is the First Equality: “la prima equalità” (Par. 15.74).

And yet, the poet is empowered by the very disagguaglianza that the pilgrim claims marks his mortality. There would be no second half of the Paradiso without dis-equality. Equality, absence of time, also means absence of language, which is a temporal medium. In the linguistic sphere, equality is silence. Dis-equality gives us language; dis-equality gives us poetic life.

Similitude, in the linguistic sphere, is death. As I note in The Undivine Comedy, the triple rhymes of Cristo/Cristo/Cristo are a sign of the silence to come, for “as difference in the form of three different rhymes gives way to identity, homology, and stasis, the poem begins to die”:

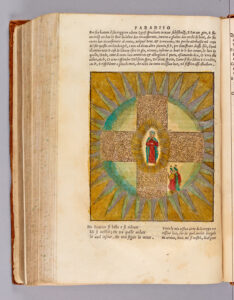

What obtains for the pilgrim within the possible world of paradise is, as is frequently the case on Dante’s circular scales, precisely the opposite of what obtains for the poet within the reality of praxis and the written poem: while the pilgrim is blocked by his disequality, the poet is empowered by the very disagguaglianza that he must, in the third canticle, nonetheless forswear. As the poem heads toward the uguaglianza of its ending, as it is deprived of the fuel of disagguaglianza, it stutters; early instances of such stuttering are the first sets of “Cristo” rhymes, located in the life of Dominic in Paradiso 12 and in the passage, toward the end of Paradiso 14, relating the miraculous appearance of Christ within the cross of Mars. These triple rhymes of Cristo / Cristo / Cristo signify not only the incommensurability of Christ to anything other than himself but also the inevitable death of terza rima; as difference in the form of three different rhymes gives way to identity, homology, and stasis, the poem begins to die.

(The Undivine Comedy, p. 219)

Return to top

Return to top