Purgatorio 6 is the canto of Italy, as Inferno 6 is the canto of Florence and Paradiso 6 is the canto of Empire. But this symmetry should not delude us: the concept of “Italy” is much murkier to Dante and his contemporaries—and much further from the modern concept—than that of Florence and that of the Holy Roman Empire.

The idea of Italy is in great part linguistic; in his linguistic treatise De Vulgari Eloquentia Dante describes Italians as “qui sì dicunt” (those who say sì as their affirmative adverb), breaking this “lingua di sì” down into various regional subgroups (DVE 1.10).

To move from language to politics, Italy is also for Dante a place of nascent tirannia, and the analysis of tirannia in Purgatorio 6 should be connected to the other canti where the term is present: Inferno 12 and Inferno 27.

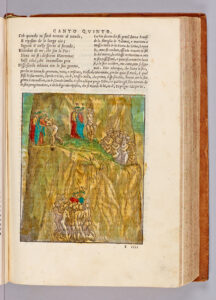

Purgatorio 6 begins with Dante surrounded by a pressing crowd of souls who died violently, eager to speak with him, some of whose names are briefly indicated by the poet. One of those thus indicated by periphrasis is the son of Marzucco Scornigiani, Gano Scornigiani, who died at the hands of Ugolino della Gherardesca’s assassins. Thus, Gano Scornigiani of Purgatorio 6, who was embroiled in the feud between Ugolino della Gherardesca and his grandson Nino Visconti (see the Commento on Inferno 33), died at the hands of a tiranno, just like Iacopo del Cassero in Purgatorio 5.

On Gano Scornigiani, I cite a passage from Dante’s Poets, p. 183:

Among these [in Purgatorio 6] is one named by periphrasis as “quel da Pisa / che fé parer lo buon Marzucco forte” (the one from Pisa who made the good Marzucco show his strength [17-18]). This is most likely Gano Scornigiani, the son of the Pisan nobleman Marzucco Scornigiani, whom Dante had occasion to meet at Santa Croce, where Marzucco lived as a priest after his retirement from the world; it was Gano’s death that gave Marzucco the opportunity to display his fortitude. lnterestingly, Gano was embroiled in the feuding between Ugolino and Nino over control of Pisa, which was the outcome of Ugolino’s bringing Nino into power as capitano del popolo in 1285; Gano, whose family had long ties with the Visconti, took Nino’s side and was killed in 1287 by Ugolino’s men.

Dante and Virgilio proceed, and see a soul sitting solitary and with great dignity. This turns out to be Sordello, a poet from Mantova (Virgilio’s birthplace) who wrote in Occitan. The question of linguistic identity is thus broached through the presence of Sordello, mentioned by Dante in the De Vulgari Eloquentia as a poet who “abandoned his native vernacular”: “patrium vulgare deseruit” (1.15.2).

Virgilio begins to introduce himself, but gets only as far as the one word “Mantua.” Perhaps he was going to say “Mantua me genuit” (Mantua gave birth to me), the epitaph that the historical Vergil was believed to have written for his own tombstone. Instead, he is impetuously interrupted by Sordello:

ma di nostro paese e de la vita ci ’nchiese; e ’l dolce duca incominciava «Mantua...», e l’ombra, tutta in sé romita, surse ver’ lui del loco ove pria stava, dicendo: «O Mantoano, io son Sordello de la tua terra!»; e l’un l’altro abbracciava. (Purg. 6.70-75)

but asked us what our country was and who we were, at which my gentle guide began “Mantua — and that spirit, who had been so solitary, rose from his position, saying: “O Mantuan, I am Sordello, from your own land!” And each embraced the other.

The embrace between Virgilio and Sordello is compared by the poet to the current state of Italy, whose citizens do not embrace each other but rather “gnaw” upon each other (“si rode,” Purg. 6.82). This metaphorical use of rodere, “to gnaw”, echoes the Ugolino episode in Inferno 32-33, where one Pisan literally gnaws on the skull of another Pisan. Given the presence in this canto of Gano Scornigiani, assassinated at the behest of Ugolino, it is evident that for Dante Ugolino is a character who assumes emblematic value far beyond his own zone of hell: Ugolino is emblematic of the tragic tirannia and family factionalism that are destroying Italy.

Immediately after the embrace of Sordello and Virgilio, something quite remarkable occurs, which has never occurred before for such a long stretch in the poem. Dante interrupts the diegesis, the narrative line, as he has in the past briefly for an address to the reader, but on this occasion he does so for the remainder of Purgatorio 6. Toward the end of the canto he describes what he is doing as a “digression” (Purg. 6.128). By calling attention to the interruption of Purgatorio 6 and giving the interruption its rhetorical label “digression”, Dante confers enormous dignity upon this singular event. The interruption or break in the narrative is emblematic of the rupture or break in comity and civility that is the tragic fate of Italy.

The digression is an explosion of political anxiety about the state of the peninsula called “Italia”, and begins with an apostrophe directed at “serva Italia”:

Ahi serva Italia, di dolore ostello, nave sanza nocchiere in gran tempesta, non donna di province, ma bordello! (Purg. 6.76-78)

Ah, abject Italy, you inn of sorrows, you ship without a helmsman in harsh seas, no queen of provinces but of bordellos!

After the apostrophe to Italy, Dante poet apostrophizes the other major actors in the tragedy of Italy, as he sees it: the clergy (Purg. 6.91), and the Emperor (Purg. 6.97). He then calls on the Emperor to come from Germany to Italy and see the devastation wrought by his political negligence. In his desperation, Dante turns to God Himself (Purg. 6.118), and asks, in the rhetorical culmination of the digression, if God has forgotten Italy. Finally, he turns to “Fiorenza mia” (Purg. 6.127) and sarcastically attacks his natal city.

In analyzing this explosive “digression” on “abject Italy”, it is important to trace the poet’s strong rhetoric, especially the turbulent sequence of his apostrophes and the string of metaphors that designate “Italia”.

Return to top

Return to top