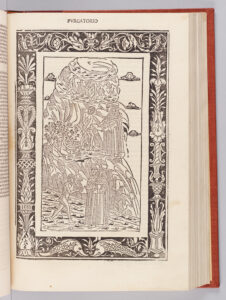

Purgatorio 4 offers a long description of an alpine climb up the steep rock face of the mountain. The description itself is arduous and difficult, and I like to think of it as the narratological equivalent of the arduous climb experienced by the pilgrim. In other words: what the pilgrim experiences on the mountain, the reader experiences at her/his desk.

Recalling some particularly steep Italian towns that nonetheless can be climbed with one’s feet (I have been to San Leo, and can testify that the main street appears almost vertical as one looks up it), Dante comments that here, on this mountain, the slope is so steep that feet are not enough. Here we need the wings of desire:

Vassi in Sanleo e discendesi in Noli, montasi su in Bismantova e ’n Cacume con esso i piè; ma qui convien ch’om voli; dico con l’ale snelle e con le piume del gran disio, di retro a quel condotto che speranza mi dava e facea lume. (Purg. 4.25-30)

San Leo can be climbed, one can descend to Noli and ascend Cacume and Bismantova with feet alone, but here I had to fly: I mean with rapid wings and pinions of immense desire, behind the guide who gave me hope and was my light.

In the above verses, Dante unpacks his metaphor of flight. He tells us, straightforwardly and almost pedagogically, that “to fly” in the Commedia equals “to desire”. First he says, “here I had to fly”, and then he explains that by “flying” he means metaphoric flight: he was required to fly with the “rapid wings and pinions of immense desire” (Purg. 4.27-29). Here Dante glosses himself, provides his own commentary. As though we are pupils who need some help in deciphering, he tells us, “Whenever I refer to flying, I am referring to desiring”.

In the lexicon of the Commedia, volare = desiderare. In the verses “ma qui convien ch’om voli; / dico con l’ale snelle e con le piume / del gran disio” (Purg. 4.27-29), Dante glosses all the flight imagery in the Commedia, retrospectively and prospectively. All flights are instances of great desire: whether of great desire that goes astray, like the desire that propelled Ulysses on his “folle volo” (Inf. 26.125), or of great desire that leads aright, like the desire that propels Dante to climb the steep face of Purgatory. The saturation of the Commedia with flight imagery — Ulyssean flight imagery — is due to the importance of desire as the impulse that governs all questing, all voyaging, all coming to know.

All the more interesting therefore, and worthy of note, are the mythological periphrases regarding “failed flyers” tucked into the lengthy explanation, offered by Virgilio, of why the sun’s rays hit Dante from the opposite direction of where they hit him on earth. Thus, to refer to the path of the sun, Virgilio refers to “la strada / che mal non seppe carreggiar Fetòn” (the path which Phaeton drove so poorly [Purg. 4.71-72]). For the motion of the sun, see the “earth clock” chart in the Commento on Purgatorio 2.

After the arduous climb, the travelers come upon the souls of another group of Ante-Purgatorial penitents: these are the lazy souls and among them is Dante’s old friend, Belacqua, who overhears the zealous pupil and his teacher. Here Dante sets up an amusing and tender contrast between the two friends: between himself, the hyper-attentive pupil, and Belacqua, a little too “chill” in life but saved nonetheless. Belacqua makes fun of his old friend with a friendly taunt: “Forse / che di sedere in pria avrai distretta!” (Perhaps you will / have need to sit before you reach the top! [Purg. 4.98-99]). He then humorously asks Dante, picking up and condensing the metaphor of the sun’s chariot from Virgilio’s ponderous lesson, if he has now “fathomed how the sun can drive his chariot on your left?”: “Hai ben veduto come ’l sole / da l’omero sinistro il carro mena? (Purg. 4.119-20).

How can we not respond to the absolute marvel of the freshness of the dialogue between Dante and Belacqua? It is a dialogue that captures the intimate rhythms of friends who run into each other on the street and exchange a few words. The profundity of the affection under the intimate banter is captured in Dante’s first words to his friend: “Belacqua, a me non dole / di te omai” (From this time on, Belacqua, / I need not grieve for you [Purg. 4.123-24]).

Return to top

Return to top