- from the darkness of hell to angelic light in the space of one canto: a recapitulation of the journey as a whole in the 50th canto

- Dante’s exceptionalism

- are the stars to blame for our lack of virtue or are we? The question of astrological determinism: we return to Cecco d’Ascoli and to the debate about Inferno 7.89 (see the Appendix to the Commento on Inferno 7), also to Dante’s programmatic deflecting of astrology in Inferno 20

- Dante’s conditional contrary-to-fact framing of the central ideological premise of his universe and of his poem

- the journey of the soul on the path of life, a poetic retelling of Convivio 4.12

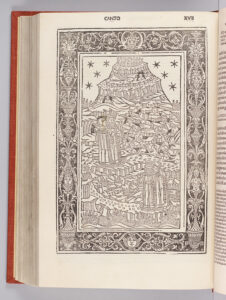

Purgatorio 16 begins in darkness likened to that of Hell (“Buio d’inferno” or “darkness of Hell” are the canto’s first words) and ends with the travelers’ emergence into light, as though they have passed in the space of one canto through a distilled version of the journey of the Commedia as a whole. Such signposts befit a canto that is the 50th of the Commedia’s one-hundred canti.

The darkness into which Dante and Virgilio are plunged is caused by the dense smoke that envelops and clouds the terrace of wrath. The pilgrim is now blinded and stays close behind his guide, in order not to “lose himself”: “Sì come cieco va dietro a sua guida / per non smarrirsi” (Just as a blind man moves behind his guide, / that he not stray [Purg. 16.10-11]). Smarrire here is the verb used in Inferno’s opening terzina to indicate that “the straight way was lost”: “ché la diritta via era smarrita” (Inf. 1.3) The idea that anger is a kind of blindness is here made literal by the poet, who enfolds the third terrace in blinding smoke. This idea is one that we still use today when we say that anger clouds our judgment and thereby makes it difficult for us to discern the correct course of action.

The blindness-causing darkness of this terrace also permits the trope that the soul Marco Lombardo will use when he, who is literally blinded, indicts the living for being intellectually blind: “Frate, / lo mondo è cieco, e tu vien ben da lui” (Brother, / the world is blind, and you come from the world [Purg. 16.65-66]). “The world is blind” is Marco Lombardo’s first reply to Dante’s query about the role of the stars in human life.

Marco Lombardo’s discourse rebuts the role of the stars and is therefore a key rebuttal of astrological determinism. I will come back to Marco’s lengthy and important discourse on determinism versus free will and right versus faulty governance on earth, stopping first to treat some of the opening gambits of the conversation between the pilgrim and the soul whom he has met.

Upon meeting, Dante speaks to Marco of his own exceptional status, first discussed in Inferno 2. He promises to tell of the wonders that have befallen him: “maraviglia udirai, se mi secondi” (you shall hear wonders if you follow me [Purg. 16.33]). He then characterizes himself as graced to see the divine court in a manner not vouchsafed to any other in modern times:

E se Dio m’ha in sua grazia rinchiuso, tanto che vuol ch’i’ veggia la sua corte per modo tutto fuor del moderno uso...(Purg. 16.40-42)

since God’s so gathered me into His grace that He would have me, in a manner most unusual for moderns, see His court . . .

On this terrace, where the pilgrim experiences “ecstatic visions” that are a mise-en-abyme of the visionary Commedia as a whole, he speaks with unusual candor of his exceptionalism.

The idea that his experience is completely unheard of in modern times — “per modo tutto fuor del moderno uso” (in a manner completely outside of modern usage [Purg. 16.42]) — testifies to the distance that Dante places between himself and the myriads of contemporary claimants to visionary insight. As I wrote in “Why Did Dante Write the Commedia? Dante and the Visionary Tradition,” Dante’s claim to Marco Lombardo is somewhat disingenuous, in that Dante wrote in a time of great visionary fervor.

Dante here constructs his visionary genealogy with the same connection to antiquity and the same bypassing of vernacular models that in Inferno 1 and Inferno 4 he uses to construct his poetic genealogy.

We remember that in Inferno 2 Dante-pilgrim chose for himself two visionary role models from antiquity: Aeneas and St. Paul. Similarly, in Inferno 1 Dante-pilgrim tells Virgilio that Virgilio is the only source of his poetic genius: “tu se’ solo colui da cu’ io tolsi / lo bello stilo che m’ha fatto onore” (you, the only one from whom I drew / the noble style that has brought me honor [Inf. 1.86-7]). And in Inferno 4 Dante constructs a poetic genealogy that makes him sixth in a “bella scola” (beautiful school [Inf. 4.94]) that includes Homer, Vergil, Ovid, Horace, and Lucan (Inf. 4.100-2).

Moreover, Dante was indeed unique in his mode of representation of his vision:

When Dante pilgrim says to Marco Lombardo that ‘‘Dio m’ha in sua grazia rinchiuso, / tanto che vuol ch’i’ veggia la sua corte / per modo tutto fuor del moderno uso’’ (God has so enclosed me in his grace / that he wants me to see his court / in a manner altogether outside of modern use [Purg. 16.40–42]), the poet is suggesting that the mode of seeing vouchsafed him is entirely unique in modern times. Reading other visions prevents us from passing over this verse, forces us to query the pilgrim’s claim to see God’s court ‘‘per modo tutto fuor del moderno uso.’’ On the one hand, this statement is historically untrue (and most likely disingenuous): Dante lived at a time of great visionary fervor. On the other hand, if we take ‘‘modo’’ to refer not only to the act of seeing but also to the act of representing, which is — for this tradition — essentially inseparable from the sight itself, how can we challenge the truth of Dante’s assertion? For visionary authors, from the humblest to the most sublime, it is not the ‘‘why’’ of the writing that is problematic but always the ‘‘how.’’ And with respect to the ‘‘how’’ there is no doubt that Dante’s text is indeed del tutto fuor del moderno uso. (“Why Did Dante Write the Commedia? Dante and the Visionary Tradition,” p. 131)

While in the Inferno it was Virgilio who most often explained the special nature of the journey that he and his charge are undertaking, in speaking to Marco Lombardo Dante is forthright in owning his own exceptionalism.

***

Marco Lombardo tells Dante who he is, leading with the place, Lombardy, whose disintegration absent imperial rule will furnish the topic of discussion in the latter part of Purgatorio 16: “Lombardo fui, e fu’ chiamato Marco” (I was a Lombard and I was called Marco [Purg. 16.46]). He describes himself as one who knew the world and loved virtue, which he calls that “valor toward which today all have slackened the bow”:

del mondo seppi, e quel valore amai al quale ha or ciascun disteso l’arco. (Purg. 16.47-48)

I knew the world’s ways, and I loved those goods for which the bows of all men now grow slack.

Marco’s words, which indicate that virtue is not prized in the world today, couple in the pilgrim’s mind with words previously expressed by Guido del Duca. Given that Guido del Duca’s words are found in Purgatorio 14, Dante here places great demands on his reader: to understand what the pilgrim is saying to Marco Lombardo at this point, the reader is required to remember or to consult the previous passage in Purgatorio 14 and to link it with the discussion in Purgatorio 16.

Dante here fosters a kind of hyper-literacy that, while present in the long history of glossing and commenting on the Bible and certain classical texts, is relatively new to the sphere of vernacular textuality. This is one of the features of the Commedia that is responsible for the immediate flourishing of a commentary tradition, beginning in the fourteenth century.

The pilgrim’s desire to clarify the doubt caused in him by the two statements coupled in his mind, Marco’s with Guido del Duca’s, escalates his need to know. He will burst, he says, if he cannot secure for himself the explanation: “ma io scoppio / dentro ad un dubbio, s’io non me ne spiego (and yet a doubt / will burst in me if it finds no way out [Purg. 16.53-4]).

As we saw, Marco remarked that while alive he loved those values that are no longer valued on earth: that valor toward which no one any longer aims his metaphorical bow. Dante remembers that Guido del Duca had described the Arno valley in similar terms, as a place whose inhabitants flee virtue as though virtue were a snake. Guido had added an either/or corollary to his statement about the inhabitants of the Arno valley, noting that they flee virtue either because of the place being ill-starred or because they have evil habits:

vertù così per nimica si fuga da tutti come biscia, o per sventura del luogo, o per mal uso che li fruga... (Purg. 14.37-39)

virtue is seen as serpent, and all flee from it as if it were an enemy, either because the site is ill-starred or their evil custom goads them so...

The conundrum arises from the unresolved either/or of the above verses: yes, we understand that the inhabitants of the Arno valley flee virtue; but do they do so because the place is ill-fated or because of their own evil customs? Which one of these two possible causes for the decadence of the Arno valley is to be considered correct? The one that is external to the inhabitants, a product of the ill-starred nature of the place, the “sventura / del luogo” (the enjambment at the end of Purg. 14.38 emphasizes the impending “misfortune” that hangs over this luogo), or the one that is internal to the inhabitants, a product of their own evil customs and habits — their “mal uso”?

This is the question that Dante now poses to Marco Lombardo, restating the two terms from Purgatorio 14 in more explicitly astrological terms, so that “sventura / del luogo” becomes “nel cielo” (in heaven) and “mal uso” becomes “qua giù” (down here):

Lo mondo è ben così tutto diserto d’ogne virtute, come tu mi sone, e di malizia gravido e coverto; ma priego che m’addite la cagione, sì ch’i’ la veggia e ch’i’ la mostri altrui; ché nel cielo uno, e un qua giù la pone. (Purg. 16.58-63)

The world indeed has been stripped utterly of every virtue; as you said to me, it cloaks — and is cloaked by — perversity. Some place the cause in heaven, some, below; but I beseech you to define the cause, that, seeing it, I may show it to others.

Is the fault for our lack of virtue to be found in the “stars” (“nel cielo” [63]) or in ourselves, “down here” (“qua giù” [63])? In other words, are we to blame for our sinful behavior? Or is our behavior determined by the stars and therefore not in our control?

The answer, in a Shakespearean nutshell, is that the fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves” (Julius Caesar I, ii, 140-41).

Dante’s answer is rather more prolix and complicated than Shakespeare’s straightforward declarative, for Dante frames Marco Lombardo’s all-important answer as a convoluted conditional contrary-to-fact. The stakes at this point are very high, involving the very integrity of the enterprise of allotting punishment for evil and reward for good.

The answer encompasses the Commedia’s central discourse on free will, a statement of the principles that hold up the entire ideological edifice of the Divine Comedy.

Marco tackles immediately and aggressively the danger of determinism in our thinking about causation in our lives. He claims that humans insist on assigning all their actions to heaven for their causes, as if all motion occurred by necessity (we recall, as discussed in the Appendix on Cecco d’Ascoli in the Commento on Inferno 7, that “necessità” is a code word for determinism). If it were thus, states Marco, then free will would be destroyed in you — in humans. And, if free will were destroyed in humans, then there would be no justice in our receiving happiness for doing good and grief for doing evil:

Voi che vivete ogne cagion recate pur suso al cielo, pur come se tutto movesse seco di necessitate. Se così fosse, in voi fora distrutto libero arbitrio, e non fora giustizia per ben letizia, e per male aver lutto. (Purg. 16.67-72)

You living ones continue to assign to heaven every cause, as if it were the necessary source of every motion. If this were so, then your free will would be destroyed, and there would be no justice in joy for doing good, in grief for evil.

If we were not acting freely, there would be no basis for assigning some souls to Heaven and others to Hell. If we were not acting freely, there would be no possibility of writing a poem like the one in which this discussion is taking place: a poem that is based on the justice — “giustizia” — of apportioning happiness — “letizia” — for good behavior (“per ben”) and grief — “lutto” — for evil behavior (“per male”).

Finally, Dante fills the philosophical void that has been present since the words on Hell’s gate: “Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore” (Justice moved my high maker [Inf. 3.4]). For, indeed, as Marco Lombardo stipulates, there can be no justice without free will: “e non fora giustizia / per ben letizia, e per male aver lutto” (and there would be no justice / in joy for doing good, in grief for evil [Purg. 16.71-2]).

Marco Lombardo’s discourse juxtaposes “libero arbitrio” (free will) with “giustizia” (justice) in verse 71 for good reason: justice can only exist if the will is free. If the will were not free, if we were constrained to flee virtue because of the ill-starred nature of the place where we live, there would be no justice in condemning our actions. The universe would then be arbitrary and capricious.

What are we to make of Dante’s syntax here, of his conditional contrary-to-fact framing of the central ideological premise of his poem and of his universe? He both formulates and staves off the most terrifying of thoughts, namely that the universe may be capricious and arbitrary, that it may not be governed by justice.

Chiavacci Leonardi characterizes Dante’s argument as a reductio ad absurdum: “La dimostrazione è fatta per assurdo (dalla premessa si giunge ad una conclusione assurda, l’ingiustizia di Dio)” (The demonstration is conducted as a reductio ad absurdum: from the premise one arrives at an absurd conclusion, the injustice of God [Purgatorio, p. 475]). But her statement that the injustice of God is an absurd conclusion seems a little too pat, given that Dante has a habit of questioning God’s justice. For instance, in Purgatorio 6, he asks: “son li giusti occhi tuoi rivolti altrove?” (have you turned elsewhere Your just eyes? [Purg. 6.120]). And Paradiso 19 contains a prolonged — and searing — meditation on God’s injustice, leading me to title my Commento on that canto “Injustice on the Banks of the Indus”.

In truth, for Dante the ideological order of the universe demands that it be ruled justly. If it is ruled justly, then those who are making choices within it and whose choices are being evaluated are doing so freely. Here, then, is the unpacking of the words on the gate of Hell in Inferno 3. Hell is just because the will is free. And here too is the reason that there can be no pity in Hell: “Qui vive la pietà quand’è ben morta” (Here pity lives when it is dead [Inf. 20.28]). The presence of pity would signal the presence of injustice.

If there is justice at work in the world, then the will is free. Dante restates this fundamental principle in a remarkable oxymoron that highlights the paradoxical idea of a will that is free but that exists in a world governed by an omnipotent and omniscient God: “liberi soggiacete” (you, who are free, are subject [Purg. 16.80]).

How can we be free if God, for Whom nothing is ever new, knows everything that we are going to do before we do it? We recall that God is “Colui che mai non vide cosa nova” — the One who never saw a new thing (Purg. 10.94) — meaning that He knows everything before it happens. This problem remains to be tackled in Paradiso. For now it is enough to state the paradox: “liberi soggiacete” (Purg. 16.80). The Italian is remarkably condensed. When we unpack, we arrive at formulations like these: You who are free are subject. You are freely subject. You are free and at the same time you are subject to God’s will.

Before leaving this central passage of Purgatorio 16 and the question of free will and the stars, I will return to the story of the astrologer Cecco d’Ascoli’s attack on Inferno 7.89, “necessità la fa esser veloce” (necessity makes her [Fortuna] swift), discussed in my Commento on Inferno 7. Cecco the astrologer accused Dante of subscribing to astral determinism, based on the code word “necessità” in Inferno 7.89. Benvenuto da Imola defended Dante on the basis of Purgatorio 16:

Sed parcat mihi reverentia sua, si fuisset tam bonus poeta ut astrologus erat, non invexisset ita temere contra autorem. Debebat enim imaginari quod autor non contradixisset expresse sibi ipsi, qui dicit Purgatorii cap. XVI: El cielo i vostri movimenti initia, Non dico tutti, ma posto ch’io ’l dica, Dato v’è lume a bene et a malitia.(Benevenuti de Rambaldis de Imola, Comentum super Dantis Aldigherij Comoediam, ed. J. P. Lacaita, Firenze: Barbèra, 1887)

But may his reverence spare me, if he were as good a poet as he was an astrologer, he would not have inveighed so boldly against the author. For he ought to imagine that the author clearly did not contradict himself, who says in chapter XVI of Purgatorio: The heavens initiate your movements; I don’t say all of them, but, were I to say it, you have been given light to discern good and evil. (Translation mine)

There are two points I would like to make in this little coda to the story told in the Commento on Inferno 7. The first is that Dante himself uses “necessità” as a code word for determinism in Purgatorio 16, accusing humans of constantly referring their actions to the heavens as though everything happens “by necessity”: “Voi che vivete ogne cagion recate / pur suso al cielo, pur come se tutto / movesse seco di necessitate” (You living ones continue to assign / to heaven every cause, as if it were / the necessary source of every motion [Purg. 16.67-69]).

The second is that Benvenuto, in furnishing Purgatorio 16 as his answer to Cecco d’Ascoli, does not cite the reductio ad absurdum argument discussed above. Rather he cites the passage that follows, of which Chiavacci Leonardi writes “alla dimostrazione per assurdo, segue la spiegazione di come veramente stanno le cose” (after the reductio ad absurdum, there follows the explanation of how things really stand [Purgatorio, p. 476]). Thus Benvenuto cites the following verses: “Lo cielo i vostri movimenti inizia; / non dico tutti, ma, posto ch’i’ ’l dica, / lume v’è dato a bene e a malizia” (The heavens set your appetites in motion — / not all your appetites, but even if that were the case, / you have received light on good and evil [Purg. 16.73-75]).

The verses cited by Benvenuto are straightforward declarative statements: you have received light that allows you to discern good and evil. Perhaps, like me, Benvenuto thought the convoluted conditional contrary-to-fact that precedes raises as many questions as it resolves.

***

After the discussion of free will and its culmination in “liberi soggiacete” (You who are free are subject [80]), Purgatorio 16 pivots to the question of governance: “Però, se ’l mondo presente disvia, / in voi è la cagione, in voi si cheggia” (Thus, if the present world has gone astray, / in you is the cause, in you it’s to be sought [Purg. 16.82-83]).

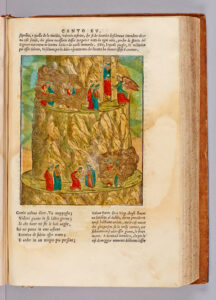

There follows the beautiful description of the newborn soul as a young female child setting forth on the path of life (Purg. 16.85–90), which echoes the voyage parable in Convivio 4.12:

The pilgrim passage of Convivio 4.12 is translated into verse at the very heart of the Purgatorio, in canto 16’s description of the newborn soul which, sent forth by a happy maker upon the path of life — “mossa da lieto fattore” (Purg. 16.89) — willingly turns toward all that brings delight: “volontier torna a ciò che la trastulla” (90). The voyage is perilous, and the simple little soul that knows nothing, “l’anima semplicetta che sa nulla” (Purg. 16.88), is distracted by the very desire that also serves as necessary catalyst and propeller for its forward motion: “Di picciol bene in pria sente sapore; / quivi s’inganna, e dietro ad esso corre, / se guida o fren non torce suo amore” (First the soul tastes the savor of a small good; / there it deceives itself and runs after, / if guide or curb does not twist its love [91-93]). (The Undivine Comedy, p. 104)

The issue of governance leads to the question: where are the institutions — the laws, the rulers — that can guide us toward the towers of the true city? The institutions once existed, indeed there were once (in a bold and wonderful metaphor) “two suns” — Empire and Church — to guide us along our two paths, the path of the world and the path of God: “Soleva Roma, che ’l buon mondo feo, / due soli aver, che l’una e l’altra strada / facean vedere, e del mondo e di Deo” (For Rome, which made the world good, used to have / two suns; and they made visible two paths — / the world’s path and the pathway that is God’s [Purg. 16.106-08]).

The metaphor of the two suns makes the Emperor and the Pope equal, and is a refutation of the typical metaphor used by political theorists at the time, in which the Pope is the sun and the Emperor is the moon, deriving his light from the Pope. This is the metaphor that Dante himself uses at the end of his political treatise, Monarchia.

Returning to Purgatorio 16, we now learn that the institutions of earthly governance have been corrupted. How? By the pernicious intermingling of secular and spiritual, of Empire and Church, a state of affairs for which the Church is primarily to blame:

Dì oggimai che la Chiesa di Roma, per confondere in sé due reggimenti, cade nel fango e sé brutta e la soma. (Purg. 16.127-29)

You can conclude: the Church of Rome confounds two powers in itself; into the filth, it falls and fouls itself and its new burden.

Marco Lombardo’s long speech can be divided thus:

I. Free will (verses 67-84): Human behavior is not determined by the stars. A transitional terzina (verses 82-84): the problem is therefore in humans and may be understood as follows:

II. 1. Humans are created good (verses 85-93): the parable of the birth of the soul and how it then goes astray (see Convivio 4.12).

2. Humans need guidance in order not to go astray (verses 94-114): guidance comes in both spiritual and temporal domains, through the Church and the Emperor. Very important is the metaphor of the “two suns” (“due soli” [107]) that used to light the world before the Church and Empire became enmeshed and corrupted.

III. Marco concludes by offering the example of corruption in Lombardia (verses 115-29): the cause is the Church.

The central canti of the Purgatorio respond to the following queries, which will be tackled in canti 16-18:

- To whom is the blame of the soul’s self-deception, as it chases after the “picciol bene” of Purgatorio 16.91, to be charged, to the stars or to itself?

- And is there any guidance to help it on its way? (canto 16)

- In what different forms can the soul’s self-deception manifest itself, i.e., what forms can misdirected desire assume? (canto 17)

- What is the process whereby such self-deception occurs, i.e., what is the process whereby the soul falls in love? (canto 18)

Return to top

Return to top