In the previous canto Dante poses the question of how it can be just to condemn the perfectly virtuous man born on the banks of the Indus. This hypothetical person is someone whom the message of Christ has not reached, and who is damned by a lack of knowledge that is not his fault and despite his perfect virtue.

The qualities of this man are much like the qualities of Virgilio. However, as discussed in the Commento on Paradiso 19, Dante uses the heaven of justice to transpose the problematic of the virtuous non-Christian from the poem’s dominant temporal or chronological axis focused on pagan antiquity — Virgilio did not know Christ because he was born before Christ — to the spatial or geographical axis of the man born on the banks of the Indus: he does not know Christ because he was born too far away from Christ, outside of the reach of Christ’s word.

In the heaven of justice, where Dante puts the legitimacy of exclusion from grace on the table for discussion, the question of how it can be just that some are damned through no fault of their own is transposed from a temporal to a geographical frame. While clearly evoking the character Virgilio, a pagan who lived and died before the birth of Christ, Dante replaces the temporal framing of the issue with a geographical frame, conjuring not a non-Christian of antiquity but a contemporary born on the banks of the Indus. This switch of frames gives a heightened relevance to a thematic that might seem far from our own concerns today.

In my view, Dante gives both a direct answer to the challenge expressed in Paradiso 19 and an indirect answer. The direct answer is what the eagle of Justice says to the pilgrim: accept your limits as a human and give up trying to understand that which human intellects are not equipped to fathom. The indirect answer takes the form of the suggestion that at the Judgment Day the Ethiopian may be saved whilst many Christians are damned. The Ethiopian of course is a non-Christian on the spatial or geographical axis, and thus belongs to the same category as the man born on the banks of the Indus.

A further indirect answer to the pilgrim’s challenge to God’s injustice comes in Paradiso 20, where Dante returns to the temporal or chronological axis, and offers a spectacular final inclusion to the Commedia’s roster of saved pagans. Delving more deeply into the pagan past than he has ever done before, Dante now features, among the souls of the heaven of justice, a just Trojan named Ripheus.

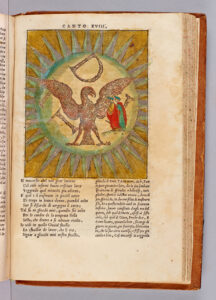

Before focusing on Ripheus, let us go back to verse 31 of Paradiso 20, where the eagle begins to present the souls that form its eye. These souls are like a hypertext linked to the basic issues of the poem, from poetic self-fashioning to virtuous pagans to the relative domains of Church and State (invoked through the presence of the emperor Constantine): “click” on these names and you will connect to core themes in every part of the poem.

The eagle’s pupil, the brightest soul, is David, the biblical king and author of the Psalms. He is a key figure in the second of the three sculpted reliefs of the terrace of pride. David is presented in Paradiso 20 in language that is a precise evocation of Purgatorio 10:

Colui che luce in mezzo per pupilla, fu il cantor de lo Spirito Santo, che l'arca traslatò di villa in villa . . . (Par. 20.37-39)

He who gleams in the center, my eye's pupil — he was the singer of the Holy Spirit, who bore the ark from one town to another . . .

The eagle’s eyebrow is formed of five souls. In order of presentation, they are: Trajan, the Roman emperor; the Biblical Hezekiah; the Roman emperor Constantine; William II of Sicily; and Ripheus the Trojan.

Trajan, like David, is presented in language that is a precise evocation of Purgatorio 10, where he is a key figure of the third sculpted relief. In the heaven of Justice he is described, as he was in the bas-relief, as “colui che . . . la vedovella consolò del figlio” (the one who . . . comforted the widow for her son [Par. 20.44-45]). Trajan is the first saved pagan of Dante’s Paradise. Unlike Constantine, whose conversion to Christianity occurred on the historical record (in other words, it “really happened”), Trajan’s conversion was a matter of legend and popular belief.

The story was that Pope Gregory the Great was so moved by Trajan’s justness that he prayed for him to come back to life. Trajan was duly resurrected, and in that brief moment of Christian experience, he converted, and died a second time as a Christian. Dante alludes to Trajan’s experience of Limbo, the first circle of Hell, when he writes:

ora conosce quanto caro costa non seguir Cristo, per l’esperienza di questa dolce vita e de l’opposta. (Par. 20.46-48)

now he has learned the price one pays for not following Christ, through his experience of this sweet life and of its opposite.

Later in Paradiso 20, in verses 109-17, the eagle offers as explanation of Trajan’s presence in heaven the entire story of Gregory’s prayers and Trajan’s resurrection, conversion, and second death, filling in the brief vignette of verses 46-48 cited above.

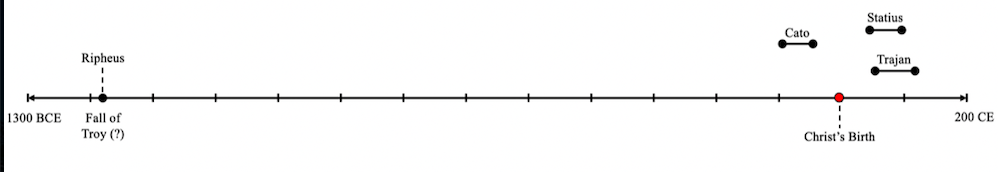

The saved pagans Trajan and Ripheus therefore pose somewhat different cultural and interpretive puzzles, since Trajan’s salvation was a well-established medieval belief by Dante’s time, while Ripheus’s salvation is a totally Dantean invention. Indeed, if we look at Dante’s four saved pagans, we find that three of the four are Dantean inventions (Ripheus, Cato, and Statius), and that only Trajan’s salvation was buttressed by a venerable and authoritative tradition.

Aside from Ripheus the Trojan, the other three saved pagans of the Commedia are all historical figures, of whom only one, Cato, lived before Christ. The Roman epic poet Statius, on the other hand, lived entirely in the Christian era, from 45 to 96 CE. Arranged in a list from earliest to latest, these are the Commedia’s four saved pagans:

- Ripheus the Trojan “dinanzi al battezzar più d’un millesmo” (more than a thousand years before baptizing [Par. 20.129])

- Cato of Utica 95 BCE–46 BCE

- Statius 45 CE–96 CE

- Trajan 53 CE–117 CE

Here is a timeline of the Commedia’s saved pagans, which reveals a curious symmetry: with respect to the souls in Limbo who lived after the birth of Christ, Dante extends his timeline far into the future; with respect to his saved pagans, Dante extends his timeline far into the past:

Despite the pilgrim’s amazement at both the first and fifth souls of the eagle’s eyebrow, the salvation of the pagan Trajan is potentially much less shocking to the informed reader of Paradiso 20, because it is buttressed by the pervasive and authoritative legend of Gregory’s intercession. Moreover, Dante had already signaled his endorsement of the legend in Purgatorio 10, where he writes that Trajan’s worth “had urged on Gregory to his great victory”: “mosse Gregorio a la sua gran vittoria” (Purg. 10.75).

The salvation of the Trojan Ripheus is another matter altogether. Who is Ripheus the Trojan? He is a tiny character in Vergil’s Aeneid, named in all human history only three times in Book 2 of the Aeneid, the book that recounts the fall of Troy. He is described by Vergil as a lover of justice, “Rhipeus, iustissimus unus / qui fuit in Teucris” (Ripheus, the most just among the Trojans [Aen. 2.426-27]):

Ripheus is mentioned three times in Aeneid II, as part of a carefully orchestrated crescendo of events: he is seen first with a group of young Trojan warriors around Aeneas, among whom is Coroebus, in love with Cassandra (II.339); then, at Coroebus’ instigation, they don the weapons of some fallen Greeks and sally forth among their enemies (II.394); finally, still in their Greek spoils, they rush to rescue Cassandra and are killed. Only now does Vergil describe Ripheus, in a way intended to heighten the pathos of his premature death: “cadit et Rhipeus, iustissimus unus / qui fuit in Teucris et servantissimus aequi / (dis aliter visum)” (Ripheus too falls, the most just among the Trojans and most observant of the right — the gods willed otherwise [II.426-428]). (Dante’s Poets, p. 254, note 65)

Dante presents Ripheus differently from the other souls in the eagle’s eyebrow, singling him out by using a rhetorical question, as though to legitimate and indeed to choreograph our readerly amazement and surprise:

Chi crederebbe giù nel mondo errante, che Rifeo Troiano in questo tondo fosse la quinta de le luci sante? (Par. 20.67-69)

Who in the erring world below would hold that he who was the fifth among the lights that formed this circle was the Trojan Ripheus?

Typically in Paradise the pilgrim does not express his own queries, but hears them expressed by the souls he encounters or by Beatrice, and yet here the amazement he experiences is such that the words erupt from his mouth: “Che cose son queste?” (Can such things be? [Par. 20.82]).

Through the medium of the eagle, the question that has formed in the pilgrim’s mind is articulated. It regards in particular the first and fifth souls of the eagle’s eyebrow, Trajan and Ripheus:

La prima vita del ciglio e la quinta ti fa maravigliar, perché ne vedi la region de li angeli dipinta. (Par. 20.100-02)

You were amazed to see the angels’ realm adorned with those who were the first and fifth among the living souls that form my eyebrow.

The poet thus links the two saved pagans, and gives his own invention of Ripheus’s conversion greater legitimacy and authority by connecting it to the story of Trajan. The two stories are presented one after the other. The eagle begins by recounting the story of the “first” soul, explaining the salvation of Trajan through the medium of Pope Gregory, and then it proceeds to recount the story of the “fifth” soul, explaining the salvation of Ripheus.

Dante parses the differences between the first and fifth souls as a temporal issue. Trajan’s salvation is offered as an example of faith in Christ’s past suffering, literally in “the feet that have suffered” (Par. 20.105). This is because Trajan came back to life through Gregory the Great’s intercession (Gregory lived c. 540 – 12 March 604), therefore centuries after the Crucifixion. Ripheus’s salvation instead exemplifies faith in the feet that have yet to suffer:

D’i corpi suoi non uscir, come credi, Gentili, ma Cristiani, in ferma fede quel d’i passuri e quel d’i passi piedi. (Par. 20.103-05)

When these souls left their bodies, they were not Gentiles—as you believe — but Christians, one with firm faith in the Feet that suffered, one in Feet that were to suffer.

Ripheus did not need to be prayed for and resurrected; rather he experienced an extreme of God’s grace while still alive, in Troy. Grace caused him to love justice; through grace his eyes were opened to future redemption:

di grazia in grazia, Dio li aperse l'occhio a la nostra redenzion futura . . . (Par. 20.122-23)

through grace on grace, God granted him the sight of our redemption in the future . . .

Through God’s grace, baptism was given to Ripheus not through the medium of a priest but directly by the three theological virtues, while he was alive in Troy:

Quelle tre donne li fur per battesmo che tu vedesti da la destra rota, dinanzi al battezzar più d’un millesmo. (Par. 20.127-29)

More than a thousand years before baptizing, to baptize him there were the same three women you saw along the chariot’s right-hand side.

These verses, intratextually vertiginous, raise even higher the stakes of Dante’s radical inventio. They take us back mentally to a precise location in the poem: to the allegorical procession of Purgatorio 29. In that procession there is the chariot whose right wheel is referred to in Paradiso 20.128, the chariot on whose right-hand side danced the three theological virtues that — as we learn in Paradio 20 — performed Ripheus’s baptism in Troy. The recounting of the allegorical procession of Purgatorio 29 is also the episode in which Virgilio’s presence is recorded for the last time in the Commedia, when the Roman poet shows his “stupor” at the sights that are unfolding. As I wrote in Dante’s Poets, Dante crafts Ripheus’s presence in heaven in such a way as to draw our attention to the exclusion of Vergil, the very author from whom he learned of Ripheus’s existence.

Paradiso 20 concludes with an apostrophe to divine predestination, which is impenetrable to human understanding:

O predestinazion, quanto remota è la radice tua da quelli aspetti che la prima cagion non veggion tota! (Par. 20.130-32)

How distant, o predestination, is your root from those whose vision does not see the Primal Cause in Its entirety!

Certainly in Paradiso 20 Dante seems to have worked hard to emulate divine impenetrability! He has created a divine tetris puzzle that we can play with ad nauseam and never quite sort out.

On the one hand the salvation of two pagans offers a welcome antidote to the eagle’s rigidity in Paradiso 19, and Ripheus’s salvation in particular has to be viewed as an example of Dante’s atypical willingness to push the envelope. In Dante’s Poets, I note that “the total omission of pagans from Paradise would not have been problematic, since, according to Foster, contemporary theologians tended to ignore the doctrine of implicit grace” (Dante’s Poets, p. 254, note 66). Here is Kenelm Foster:

Catholic theology by and large did not much concern itself with the ultimate destiny, in God’s sight, of the pagan world whether before or since the coming of Christ …. The concept itself of fides implicita was not lacking … but it was hardly a central preoccupation of theologians, nor, in particular, do its implications for an assessment of the spiritual state of the world outside Christendom seem to have been taken very seriously. (“The Two Dantes,” pp. 171-72).

Therefore, Dante’s passionate interest in the doctrine of implicit grace, dramatized in the story of Ripheus, is very much his own contribution and one that makes for a sense of greater openness and possibility in his imagined universe.

On the other hand, Dante picks as his messenger of hope a character who, necessarily, because of his provenance in the Aeneid, brings with him not just hope but complicated feelings of loss and exclusion. Dante manages the story of Ripheus in such a way as to implicate both the author of the Aeneid, Vergil, and the memory of the character, Virgilio, a virtuous but unsaved pagan whom we last saw viewing the very same theological virtues involved in Ripheus’s baptism. The memory of Virgilio certainly complicates and perhaps even diminishes our pleasure at encountering a saved pagan from deepest antiquity now ensconced in heavenly glory.

Return to top

Return to top