The “splendore” (splendor [Purg. 15.11]) with which Purgatorio 15 begins is an introduction to the “luce rifratta” (reflected light [Purg. 15.22]) of Paradise, where all the souls reflect the light of God — literally. Here, the pilgrim is struck so forcefully by the light that he has to look away:

così mi parve da luce rifratta quivi dinanzi a me esser percosso; per che a fuggir la mia vista fu ratta. (Purg. 15.22-24)

so did it seem to me that I had been struck there by light reflected, facing me, at which my eyes turned elsewhere rapidly.

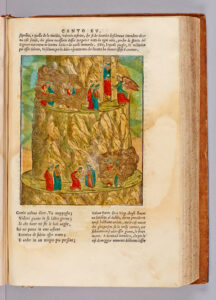

The first segment of Purgatorio 15 is the conclusion of the terrace of envy: the light by which the pilgrim is struck comes from the angel who removes the second “P” from Dante’s brow. There follows the recitation of a Beatitude and the passage upwards to the third terrace, the terrace of anger.

To pass the time while climbing the pilgrim asks his guide in verses 44-45 what the “spirit of Romagna” (Guido del Duca) meant when he used the terms “divieto” and “consorte”:

Che volse dir lo spirto di Romagna, e ‘divieto’ e ‘consorte’ menzionando? (Purg. 15.44-45)

What did the spirit of Romagna mean when he said, ‘Sharing cannot have a part’?

The pilgrim is referring to Guido del Duca’s bitter rhetorical question from the preceding canto:

o gente umana, perché poni ’l core là ’v’è mestier di consorte divieto? (Purg. 14.86-87)

o humankind, why do you set your hearts there where our sharing cannot have a part?

Humans, Virgilio explains, insist on directing their love and desire “there where sharing cannot have a part”. In other words, we humans desire objects that are diminished when shared:

Perché s’appuntano i vostri disiri dove per compagnia parte si scema, invidia move il mantaco a’ sospiri. (Purg. 15.49-51)

For when your longings center on things such that sharing them apportions less to each, then envy stirs the bellows of your sighs.

If only we would direct our longings upward, toward heaven, we would find that there would be no need for envy. This is so because in heaven, the more there are who share (“the more there are who say ‘ours’” [Purg. 15.55]), the more that each one possesses of the good, and the more love there is altogether:

ché, per quanti si dice più lì “nostro”, tanto possiede più di ben ciascuno, e più di caritate arde in quel chiostro. (Purg. 15.55-57)

for there, the more there are who would say “ours,” so much the greater is the good possessed by each—so much more love burns in that cloister.

Guido del Duca’s rather cryptic statement in Purgatorio 14 frames envy as the natural consequence of human desire for earthly goods that are necessarily diminished by sharing. Nor is he wrong, in material terms: as a piece of material pie is diminished if I share it with you, so the metaphoric pie chart used by economists to demonstrate proportional distribution is all about divvying up and thereby diminishing. In Purgatorio 15, Virgilio reframes the issue as a discussion of spiritual goods that are increased by sharing.

Spiritual goods follow a principle of divine multiplication rather than terrestrial division: the more that everyone loves the more love there is to go around.

But the pilgrim is resistant. He restates his skeptical question with even more emphasis on the logical and mathematical certainty that a good divided among many possessors is necessarily distributed into smaller parts than if it were divided among fewer possessors, thus making each possessor less rich:

Com’esser puote ch’un ben, distributo in più posseditor, faccia più ricchi di sé, che se da pochi è posseduto? (Purg. 15.61-63)

How can a good that’s shared by more possessors enable each to be more rich in it than if that good had been possessed by few?

Having formulated the distinction between the material viewpoint and the spiritual viewpoint as clearly and sharply as possible, the poet has Virgilio reconfirm the spiritual calculus, whereby the more souls there are who love each other, the more love there is overall for them to enjoy:

E quanta gente più là sù s’intende, più v’è da bene amare, e più vi s'ama, e come specchio l’uno a l’altro rende. (Purg. 15.73-75)

And when there are more souls above who love, there's more to love well there, and they love more, and, mirror-like, each soul reflects the other.

After the discourse on the distribution of love come the examples of the virtue, gentleness or meekness, that corresponds to the vice of anger. The three examples of gentleness are, as always, taken first from the life of the Virgin Mary, followed by a classical/biblical mix: Mary’s gentleness with her son, the classical Pisistratus’ gentleness with his daughter’s suitor (these two examples are both very interesting as windows into thinking about the family and normative interactions within it), and the biblical St. Stephen’s meek acceptance of his martyrdom.

The examples on the terrace of anger are experienced by Dante not as visual art (the terrace of pride) or sound-bites flying through the air (the terrace of envy) but, remarkably, as “ecstatic visions”: visions that he sees inside his mind but that are not thereby lessened in their truth-value. In this way the author of the Commedia, a great visionary poem, thematizes the visionary experience itself: what it is to be “caught up” like St. Paul (“tratto” in Purgatorio 15.86, analogous to “ratto” in Purgatorio 9.24).

Chapter 7 of The Undivine Comedy tackles the fundamental issue of visionary experience, which Dante thematizes in the Purgatorio: in the three dreams that punctuate his climb up the mountain (Purgatorio 9, Purgatorio 19, Purgatorio 27), in the ecstatic visions of the terrace of wrath at the center of the Commedia (Purgatorio 15 and 17), and in the vision he is afforded of all Christian history at the end of this cantica. The expression “non false errors” of the title of Chapter 7 comes from Purgatorio 15, where Dante describes the ecstatic visions he experiences on the terrace of wrath as “non falsi errori” (117).

As I write in The Undivine Comedy: “The hallmarks of the visionary style are never more in evidence than in the rendering of the apparitions of the terrace of wrath, which appear and disappear like bubbles within water” (p. 151). The section of Purgatorio 15 devoted to the ecstatic visions that afford examples of humility, along with the section of Purgatorio 17 devoted to the ecstatic visions that afford examples of wrath, offer a veritable phenomenology of visionary experience. Here we find the only use of the word “ecstatic” in all Dante’s work:

Ivi mi parve in una visione estatica di sùbito esser tratto e vedere in un tempio più persone . . . (Purg. 15.85-87)

There I seemed, suddenly, to be caught up in an ecstatic vision and to see some people in a temple...

In this “phenonmenology of vision” Dante offers insight into how he perceived visionary experience, an experience that after all underlies the entire Commedia:

Quando l’anima mia tornò di fori a le cose che son fuor di lei vere, io riconobbi i miei non falsi errori. (Purg. 15.115-17)

And when my soul returned outside itself and met the things outside it that are real, I then could recognize my not false errors.

The Undivine Comedy treats the concept of “non falsi errori” from Purgatorio 15.117 as a foundational index of Dante’s overall textual strategies: see Chapter 1, p. 13, and Chapter 7, “Nonfalse Errors and the True Dreams of the Evangelist.” The Evangelist of the chapter title is St. John, writer of the Apocalypse (in Dante’s time the St. John who wrote the Apocalpyse was not distinguished from St. John the Evangelist, who wrote the Gospel of John): the Apocalypse is precisely a “true dream” or “vision”, one that Dante references in Inferno 19 and that is the key intertext of the visionary procession at the end of Purgatorio.

Visionary experience is framed and defined by Dante in the above tercet that coins the idea of “not false errors”: an order of reality that is in error with respect to “ordinary” reality but that is nonetheless not false. A phenomenology of visionary experience is presented via the examples of meekness in Purgatorio 15 and of anger in Purgatorio 17.

Return to top

Return to top