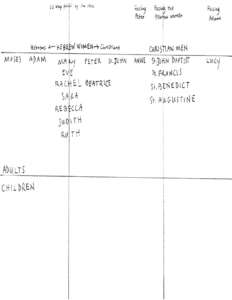

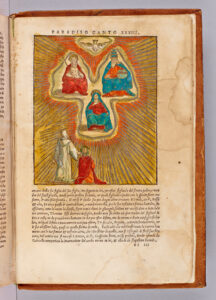

Saint Bernard guides the pilgrim on a visual tour of the rose, pointing out by name some of the great souls whom Dante can now see in their places in the heavenly ranks. Saint Bernard gives not only their names, but also their placement in the divine order, so that we are made cognizant of the ranking or hierarchy of a section of the Empyrean. At the end of this commentary are my flat diagram of the circular rose and the much more elegant diagrams from Giuseppe Di Scipio’s The Symbolic Rose in Dante’s ‘Paradiso’ (Ravenna: Longo, 1984).

The rose turns out to be riddled with difference, with individuality. It is arranged in a vertical hierarchy:

puoi tu veder così di soglia in soglia giù digradar, com’io ch’a proprio nome vo per la rosa giù di foglia in foglia. (Par. 32.13-15)

these you can see, from rank to rank as I, in moving through the Rose, from petal unto petal, give to each her name.

And the rose is divided horizontally as well. Its bottom half contains the souls of innocent children who died before they had power of choice:

ché tutti questi son spiriti asciolti prima ch'avesser vere elezioni. Ben te ne puoi accorger per li volti e anche per le voci puerili, se tu li guardi bene e se li ascolti. (Par. 32.44-48)

for all of these are souls who left their bodies before they had the power of true choice. Indeed, you may perceive this by yourself— their faces, childlike voices, are enough, if you look well at them and hear them sing.

In this section of the rose, therefore, seating is in no way related to one’s individual merit, but depends on the merit of others and also on “certain conditions”:

per nullo proprio merito si siede ma per l’altrui, con certe condizioni . . . (Par. 32.42-43)

sit souls who are there for merits not their own but—with certain conditions—others’ merits . . .

The specific merits of others and specific conditions that have given these infants their seats in the rose will be presented in verses 73-87, where we shall arrive in due course. For now, it is important to know that the merits of others under certain conditions are such as to free these infants from original sin, and therefore to guarantee them salvation. Had they not been saved, the issue of how to arrange them hierarchically in heaven would not have been posed, since infants who have not been exempted from original sin are in Limbo.

So, here, in the rose, despite their lack of merit, the infants are hierarchically arranged, some lower and some higher, some più and some meno. This is the fact that engages the pilgrim in a final bout with a deeply disturbing dubbio, an intellectual uncertainty whose hold on his imagination is indicated by Bernard’s repetition of the verb dubbiare: “Or dubbi tu e dubitando sili” (But now you doubt and, doubting, do not speak [49]).

I find it extremely impressive that Dante manages to have a dubbio, that he can still be dubitando, even this high up in Paradise, at the very threshold of the beatific vision. And what is Dante’s final dubbio? It is a variant of his nagging obsession with fairness and justice, expressed all through Paradise, starting with his asking Piccarda in Paradiso 3 whether she wishes she were higher up, and finding most poignant expression in the heaven of justice, where in Paradiso 19 he voices his concern about the justice that could condemn a perfectly virtuous man born on the banks of the Indus who had no way of knowing about Christ.

His concern in Paradiso 32 relates to the justice inherent in diversity of grace, with respect to placing the infants in a hierarchy: how can it be just to order them hierarchically, when they did not live long enough to have any merit? Let me underscore what is so noteworthy about this issue and its placement here, at the very threshold of the beatific vision, as the final dubbio of Paradiso. There can be no concern about these infants: they are saved, they are blessed, they are with God. So what is Dante so worried about?

The fact that Dante can be so worried even here, about blessed souls, shows us that it is truly the principle that worries him, and not just the outcome. He is made unhappy by the very fact that there are blessed souls who cannot contribute any merit to the equation of merit and grace by which souls are hierarchically arranged, and who yet are placed in paradise in an order.

The final dubbio of the Paradiso is essentially its first, and exhibits the same preoccupation with unequally proportioned grace that has troubled the pilgrim throughout his ascent. But the issue has never been more starkly raised than here, because never before has individual merit been totally excluded from the equation, leaving only the inexplicable variable, the incomprehensible component: God’s grace.

The theological context around this issue is also very interesting, and throws Dante’s anomalous concerns into stark relief. Both Thomas and Bonaventure posit equality in degrees of grace for infants, while Dante differs in positing diversity of grace. As Steven Botterill writes: “for Dante diversity in degrees of grace is the norm — is, indeed, a structural principle in the Empyrean — and to this extent his doctrine clearly differs from that of either of these two predecessors” (Botterill, “Doctrine, Doubt and Certainty: Paradiso XXXII.40-84”, p. 33; for full reference, see Coordinated Reading).

Dante frequently comes to what seems like a radical or at least unusual position simply by following the logic of an argument to its extreme. He follows the logic of diversity of grace to its extreme and thereby extends diversity of grace — and his concerns about that principle — to saved infants. Similarly, he follows the logic of implicit faith to its extreme, and thereby extends salvation to selected virtuous pagans.

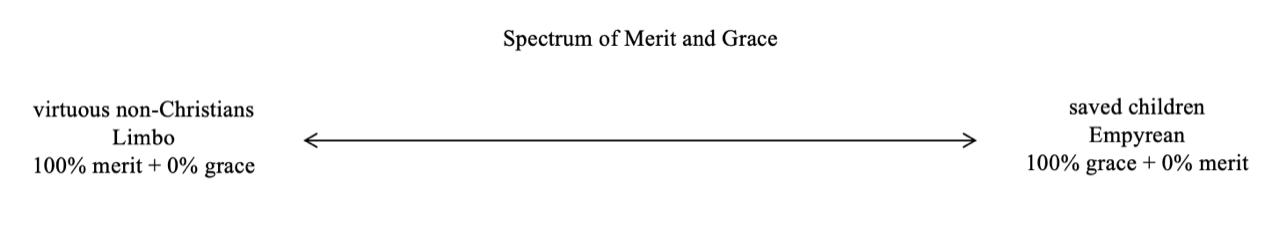

All through Paradiso Dante has emphasized that the formula for salvation is: merit + grace. His concern with the saved infants allows us to see a connection to virtuous non-Christians and to realize that, in fact, Dante has been studying the twin components of beatitude — merit plus grace — from every possible perspective. He found in the virtuous non-Christians and the saved infants an opportunity to ponder the two extreme cases: while a virtuous non-Christian poses an instance of an exceptionally meritorious soul who is lacking in grace, a saved infant presents the opposite configuration, a soul that is lacking merit and possesses only grace.

These two groups constitute the two extreme cases of the implicit spectrum that Dante devises. The two extremes are 100% merit and 0% grace (in the case of the virtuous non-Christians) and 100% grace and 0% merit (in the case of the saved children):

Both these extreme cases claim Dante’s attention because of possible injustice: the injustice of a virtuous person condemned to Limbo is discussed in Paradiso 19, where the pilgrim challenges the justice that condemns those who had no opportunity to know of Christ’s existence. Here, in Paradiso 32, the pilgrim confronts the injustice inherent in any unjustified hierarchy, which in this case is the hierarchy that arranges saved infants entirely based on the grace meted out to them.

A further indication of the link between these two extreme cases lies in the fact that both groups — both the 100% merit group and the 100% grace group — are connected to Limbo. The virtuous pagans who are not saved by grace (compare Ripheus, who was saved by grace in Troy, as described in Paradiso 20) reside in Limbo. And the infants who do not meet the conditions for salvation based on the merits of others, as outlined in Paradiso 32, also reside in Limbo.

Hence, almost all virtuous pagans reside in Limbo. As discussed in the Commento on Inferno 4, the placement of virtuous pagans in Limbo is already a huge and uniquely Dantean concession to the requirements of justice, as Dante sees those requirement.

Limbo is also the home of unbaptized infants: the infants who live after the birth of Christ but are not baptized. This issue is clarified in the list of the conditions whereby infants can be saved based on the merits of others. By the same token, if the conditions are not met, then the infants are damned, and in Limbo.

With respect to the damnation to Limbo of unbaptized infants, Dante is following orthodoxy. With respect to the damnation to Limbo of virtuous pagans, Dante is writing a new theology of Limbo. The coincidence of the two groups in Limbo is uniquely Dantean. And the connection between the two groups that is established by their residence in Limbo draws our attention to a meditation that runs the entire length of the poem.

***

Saint Bernard’s “resolution” of Dante’s dubbio consists of a series of assertions, not proofs. He asserts that within the divine realm no arbitrariness can exist, for in God’s domain nothing can be a matter of chance:

Dentro a l’ampiezza di questo reame casüal punto non puote aver sito . . . (Par. 32.52-53)

Within the ample breadth of this domain, no point can find its place by chance . . .

Having thus stated as fact what he does not prove, Saint Bernard derives as a corollary of his unproven assertion the justness of the children’s collocation. Given that there is no arbitrariness in God’s realm, the children cannot have been arranged arbitrarily, “sine causa” (59). A cause for their being more and less excellent among themselves must therefore exist:

e però questa festinata gente a vera vita non è sine causa intra sé qui più e meno eccellente. (Par. 32.58-60)

and thus these souls who have, precociously, reached the true life do not, among themselves, find places high or low without some cause.

Here Saint Bernard has baldly uttered the issue of great concern, the issue that consumes Dante: the infants are, through no merit of their own, più e meno eccellenti.

One last time, più e meno is the herald of difference, as it was in the first terzina of Paradiso. Now it ushers in a passage that offers the poem’s last use of diversamente, its last use of differente, and its last use of differire:

Lo rege per cui questo regno pausa in tanto amore e in tanto diletto, che nulla volontà è di più ausa, le menti tutte nel suo lieto aspetto creando, a suo piacer di grazia dota diversamente: e qui basti l’effetto. . . . . . . . . . . . . Dunque, sanza mercé di lor costume, locati son per gradi differenti, sol differendo nel primiero acume. (Par. 32.61-66 and 73-75)

The King through whom this kingdom finds content in so much love and so much joyousness that no desire would dare to ask for more, creating every mind in His glad sight, bestows His grace diversely, at His pleasure— and here the fact alone must be enough. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Without, then, any merit in their works, these infants are assigned to different ranks— proclivity at birth, the only difference.

Bernard follows these assertions with an explanation of the conditions that allow for the salvation of infants. As though to manifest the arbitrariness that Bernard just denied, these verses are among the Commedia’s most dogmatic, outlining the historical conditions that govern the salvation of infants. From the time of Adam to Abraham the faith of the parents is required, from the time of Abraham to Jesus circumcision is a prerequisite, and after Christ, in “the time of grace” (82), salvation depends on baptism:

Bastavasi ne’ secoli recenti con l’innocenza, per aver salute, solamente la fede d’i parenti; poi che le prime etadi fuor compiute, convenne ai maschi a l’innocenti penne per circuncidere acquistar virtute; ma poi che ’l tempo de la grazia venne, sanza battesmo perfetto di Cristo tale innocenza là giù si ritenne. (Par. 32.76-84)

In early centuries, their parents’ faith alone, and their own innocence, sufficed for the salvation of the children; when those early times had reached completion, then each male child had to find, through circumcision, the power needed by his innocent member; but then the age of grace arrived, and without perfect baptism in Christ, such innocence was kept below, in Limbo.

Hence, the salvation of infants depends, as we learned at the beginning of this discourse, on “certe condizioni” (43). These conditions seem capricious as justification for exclusion from salvation — much as does birth on the banks of the Indus. Once more Dante has rotated the axis, moving from the geographical axis of Paradiso 19 back to the temporal axis, but now shifting it from pagans of antiquity to children throughout history from antiquity to the present.

If a child lived during the earliest times, the faith of the parents is sufficient justification; beyond those times and before the time of Christ, circumcision is required. While most retain “penne” (feathers) in verse 80 and construe the verse to refer to the “innocent wings” of the infant boys, which must be strengthened by circumcision, the commentator Daniello opted for “pene” (penis). Mandelbaum follows Daniello’s reconstruction in his translation; hence the reference to “member” in Mandelbaum’s translation above.

I do not personally follow Daniello or Mandelbaum, and believe that the more common reading, which takes “penne” or “feathers” as a synecdoche for the wings of these souls, is the more persuasive. Dante will return to the metaphor of our human “wings” in the end of this canto.

In this passage Dante draws attention to the nub of his concern; by laying stress on the apparent arbitrariness of God’s law, as of God’s choice of Jacob over Esau (67-72), Dante confronts his worst nightmare and affirms his belief in a grace that, by eternal law (“etterna legge” [55]), is allotted as justly — “giustamente” (56) — as the ring fits the finger (55-57). God bestows His grace as He pleases, “a suo piacer” (65); on the basis of God’s assignment, which we must assume to be just, and irrespective of any personal merit, we differ among ourselves.

***

Having thus taken care of Dante’s last dubbio, Saint Bernard in verse 85 instructs Dante to look at the Virgin, celebrated by the angel Gabriel, described in courtly language with the terms baldezza and leggiadria (109). In verse 115 Bernard resumes the tour of the rose. Toward the end of the canto Saint Bernard makes a fascinating reference to Dante’s visionary sleep: the verse “perché ’l tempo fugge che t’assonna” (139) and its fraught reception is discussed in detail in The Undivine Comedy, pages 144-47.

Because the time of Dante’s visionary sleep is coming to an end, it is time for him to turn his eyes directly on the “primo amore” (142) and to penetrate the divine light as far as he can with his gaze:

e drizzeremo li occhi al primo amore, sì che, guardando verso lui, penètri quant’è possibil per lo suo fulgore. (Par. 32.142-44)

and turn our vision to the Primal Love, that, gazing at Him, you may penetrate— as far as that can be—His radiance.

Dante will penetrate the radiance “quant’è possibil”, as much as is possible for him. In other words, he will penetrate the divine as much as may be achieved by his specific and eternally differentiated historical self. Here is history again, less stark and dogmatic than in its scansion of the requirements for infant salvation, but rooted in the same principle of ontological difference.

But, in order for the pilgrim to achieve anything at all, they must first pray. Otherwise, if he relies on his own powers — on his own wings — he risks falling back rather than moving beyond: “ne forse tu t’arretri / movendo l’ali tue, credendo oltrarti” (But lest you now fall back when, even as you move your wings, you think that you advance [145-46]). The use of the wing metaphor to refer to Dante’s powers of ascent, in the verses just cited, indicates to my satisfaction that Daniello was wrong to substitute “pene” for “penne” in verse 80.

To avoid falling back, they will pray for help to the one who can help him, the intercessor per eccellenza of Catholic theology, the Virgin Mary. But the prayer to the Virgin itself does not begin until Paradiso 33. And so this canto concludes suspended, the only canto of the Commedia to end with a colon in modern editions. In fact, Paradiso 32 is the only canto in the poem to end without benefit of a conceptual full stop. In the last verse Saint Bernard begins to pray, so that the canto ends thus:

E cominciò questa santa orazione: (Par. 32.151)

And he began this holy supplication:

Canto 32 is enjambed — it jumps!

Return to top

Return to top