The initial two-thirds of Paradiso 14, roughly speaking, comprises the last section devoted to the heaven of the sun. In Paradiso 14.82-84, Dante-pilgrim and his guide transition to the heaven of Mars.

The opening of Paradiso 14, “Dal centro al cerchio, e sì dal cerchio al centro” (1), beautifully recapitulates the dominant image of the heaven of wisdom: that of the wise men who are as points on the circumference of a cerchio, all equidistant from the truth at the centro.

In context, the verse is part of a passage in which the poet compares the speech patterns of Beatrice and St. Thomas to water circling in a vase:

Dal centro al cerchio, e sì dal cerchio al centro movesi l’acqua in un ritondo vaso, secondo ch’è percosso fuori o dentro: ne la mia mente fé sùbito caso questo ch’io dico, sì come si tacque la gloriosa vita di Tommaso, per la similitudine che nacque del suo parlare e di quel di Beatrice . . . (Par. 14.1-8)

From rim to center, center out to rim, so does the water move in a round vessel, as it is struck without, or struck within. What I am saying fell most suddenly into my mind, as soon as Thomas’s glorious living flame fell silent, since between his speech and that of Beatrice, a similarity was born.

The opening of Paradiso 14 is thus a simile — and note the hyper-literary word “similitudine” in verse 7, a hapax in the Commedia — that compares water moving from the circumference of a vase to its center and back again to waves of discourse, to currents of language. It is therefore a perfect mise-en-abyme of the heaven of the sun itself, whose intense meta-narrative focus I discuss in great detail in Chapter 9 of The Undivine Comedy.

Beatrice announces that Dante has another dubbio. He now wants to know about the resurrected body, its degree of luminosity, and how the eyes of the blessed will be able to tolerate it:

Diteli se la luce onde s’infiora vostra sustanza, rimarrà con voi etternalmente sì com’ell’è ora; e se rimane, dite come, poi che sarete visibili rifatti, esser porà ch’al veder non vi nòi. (Par. 14.13-18)

Do tell him if that light with which your soul blossoms will stay with you eternally even as it is now; and if it stays, do tell him how, when you are once again made visible, it will be possible for you to see such light and not be harmed.

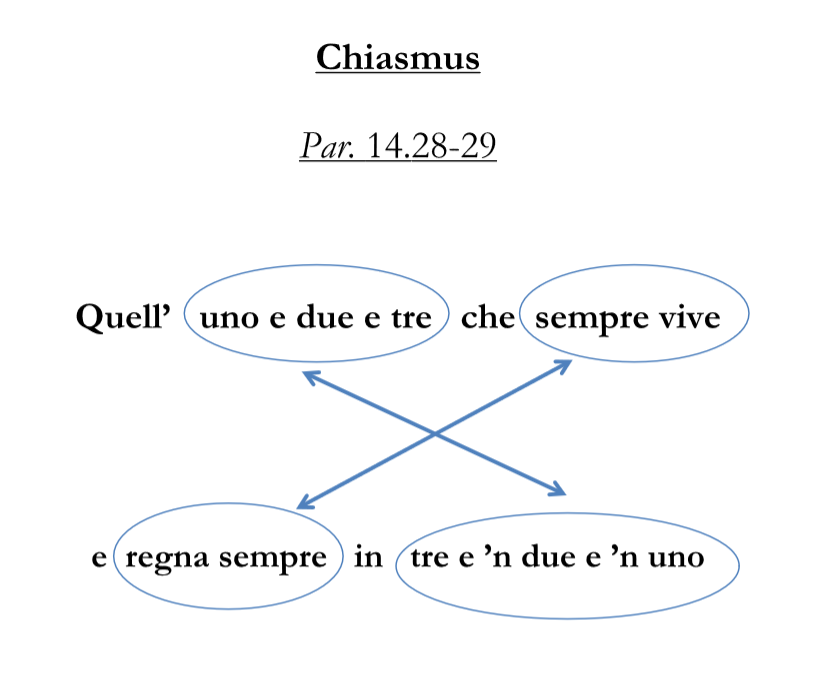

Before an answer is forthcoming, the souls sing together three times of the Trinity, expressed in chiasmic fashion as “Quell’uno e due e tre che sempre vive / e regna sempre in tre e ’n due e ’n uno” (That One and Two and Three who ever lives / and ever reigns in Three and Two and One [Par. 14.28-29]). The chiasmus can be visualized thus:

Solomon, described as the “brightest light in the smaller circle” (Par. 14.34-35), takes the task of answering the pilgrim’s question. This language, like the canto’s opening salvo, is recapitulatory with respect to the “events” of the heaven of the sun. The smaller circle is the first of the two concentric circles that now surround the pilgrim and Beatrice, the one that formed around them first, in Paradiso 10. Solomon’s being the “brightest light” in the first circle takes us back to the pilgrim’s curiosity as to the reason for Solomon’s relative importance: a query that is embedded in the language of St. Thomas in Paradiso 10, articulated by St. Thomas in Paradiso 11, and answered by St. Thomas in Paradiso 13.

Solomon now speaks in “a modest voice” — perhaps, says Dante (it is quite magical, this “forse”), like the voice with which the angel spoke to Mary:

E io udi’ ne la luce più dia del minor cerchio una voce modesta, forse qual fu da l’angelo a Maria . . . (Par. 14.34-36)

And I could hear within the smaller circle’s divinest light a modest voice (perhaps much like the angel's voice in speech to Mary) . . .

This extraordinary moment indicates that Dante had conjured for himself the quality of the angel Gabriel’s voice during the Annunciation. Did he do this while looking at a painting? Dante now shares with us that Solomon speaks with a modest voice, perhaps like the voice with which Gabriel spoke to Mary: “una voce modesta” (Par. 14.35). Later in the Paradiso, Dante will continue his conjuring of the Annunciation, transcribing his version of Gabriel’s song to Mary.

This passage is not only imaginatively resonant but rich with meaning. It reminds us of Christ’s birth, the event that was presaged by the Annunciation. Christ’s birth was discussed in Paradiso 13, in the context of the discussion of the most perfect humans, Christ and Adam. Moreover, the allusion to the Annunciation, the moment in which the angel tells Mary that she will become a mother, prepares us for this canto’s later revelation about mothers and fathers and other beloveds, all of whom we will live more dearly once we are reunited with our resurrected bodies.

The connection between our bodies and our loves is thus already implicit in the verses comparing Solomon’s vocal delivery to that of Gabriel at the Annunciation.

This connection will now be unpacked by Solomon, who explains to Dante that the brightness of a soul in heaven reflects the love that it feels, and that the soul’s love reflects the degree of vision allotted to it, an amount determined by its own merit plus the inscrutable quotient of grace:

La sua chiarezza [A] séguita l’ardore [B];

l’ardor la visione [C], e quella è tanta,

quant’ha di grazia [D] sovra suo valore.

(Par. 14.40-42)

La sua chiarezza [A] séguita l’ardore [B]; l’ardor la visione [C], e quella è tanta, quant’ha di grazia [D] sovra suo valore. (Par. 14.40-42)

Its brightness takes its measure from our ardor, our ardor from our vision, which is measured by what grace each receives beyond his merit.

When the soul is dressed again in its glorified flesh — “carne gloriosa e santa” in verse 43 — every feature of the above formula will be heightened, since (as we learned in Inferno 6 and Inferno 13), we are more perfect when our bodies and souls are united:

Come la carne gloriosa e santa fia rivestita, la nostra persona più grata fia per esser tutta quanta . . . (Par. 14.43-45)

When, glorified and sanctified, the flesh is once again our dress, our persons shall, in being all complete, please all the more . . .

As a result of being more perfect, after the resurrection all the measurements expressed earlier — the degree of brightness, the degree of love, the degree of vision, the degree of grace — will be increased.

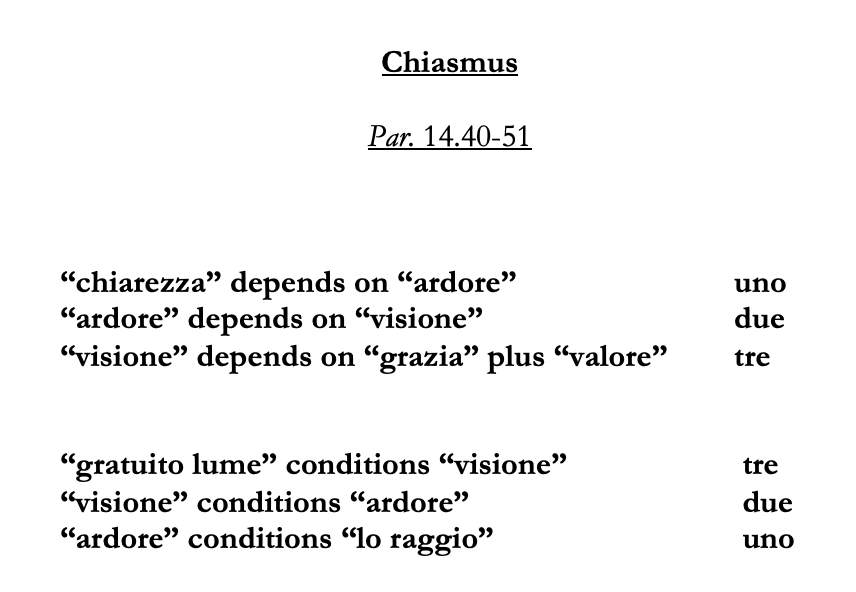

Dante expresses the new post-resurrection reality by reversing the order of verses 40-42, thus creating another chiasmus: ABCD reverses to DCBA. Where first he moved from the soul’s brightness (A) to its love (B) to its vision (C) to its amount of grace (D), now he reverses, moving from the soul’s grace (D) to its vision (C) to its love (B), and thence to its brightness (A):

per che s’accrescerà ciò che ne dona

di gratuito lume [D] il sommo bene,

lume ch’a lui veder ne condiziona;

onde la vision [C] crescer convene,

crescer l’ardor [B] che di quella s’accende,

crescer lo raggio [A] che da esso vene.

(Par. 14.46-51)

per che s’accrescerà ciò che ne dona di gratuito lume [D] il sommo bene, lume ch’a lui veder ne condiziona; onde la vision [C] crescer convene, crescer l’ardor [B] che di quella s’accende, crescer lo raggio [A] che da esso vene. (Par. 14.46-51)

therefore, whatever light gratuitous the Highest Good gives us will be enhanced— the light that will allow us to see Him; that light will cause our vision to increase, the ardor vision kindles to increase, the brightness born of ardor to increase.

There is yet another glorious chiasmus, as verses 40-51 effectively give us a “writ large” version of the uno/due/tre chiasmus in verses 28-29:

At the thought of receiving their resurrected flesh, the souls of the wise men surrounding Dante and Beatrice call out “Amen”, overjoyed that they will be getting their bodies back. Dante specifies that they are happy not just for themselves, but because of their loved ones: their fathers and mothers (“mamme”) and others who were dear to them before they became eternal flames.

Very significant here is the nuance of causality that Dante suggests between the restoration of the flesh and our ability to express and experience love. We know, from Inferno 6 that the restoration of our bodies at the Last Judgment will make a “more perfect union”. In their perfected — completed — state, the damned will suffer more, and the blessed will be more blissful: “quanto la cosa è più perfetta, / più senta il bene, e così la doglienza” (when a thing has more perfection, / so much the greater is its pain or pleasure [Inf. 6.107-8]).

Now Dante suggests that an important feature of the Resurrection, of the recovery of one’s body, is that we will be able to love more perfectly.

These blessed souls, not in the heaven consecrated to love but in the heaven consecrated to wisdom, make manifest their “desire for their dead bodies” (Par. 14.63), and the poet opines that maybe (another magical “forse”) their desire is “not only for themselves”, but for their beloveds:

Tanto mi parver sùbiti e accorti e l’uno e l’altro coro a dicer «Amme!», che ben mostrar disio d’i corpi morti: forse non pur per lor, ma per le mamme, per li padri e per li altri che fuor cari anzi che fosser sempiterne fiamme. (Par. 14.61-66)

One and the other choir seemed to me so quick and keen to say “Amen” that they showed clearly how they longed for their dead bodies— not only for themselves, perhaps, but for their mothers, fathers, and for others dear to them before they were eternal flames.

This is the positive version of what we saw in negative form in Inferno 13. There we saw a disdain for the body that expresses itself ultimately in suicide; here we see a value placed on the body that extends into Paradise. This value includes — so importantly — an acknowledgement that love is an embodied experience.

The idea that love is an embodied experience is built into the story of the transcendent principle taking human form in order to be born as the son, not just of God, but, as we saw earlier, of Mary. The special role of mothers is captured in the stunning use of “mamme”, and in the remarkable rhyme of “mamme” (64) — word of the flesh — with “fiamme” (66) — word of the spirit.

A third circle of souls now forms around the two that we have already encountered, thus completing the Trinitarian resonances of this heaven. These souls will not be named, and Dante transitions to the heaven of Mars in Paradiso 14.83-84.

The heaven of Mars feels very different, right from the start. It is ruddy in color, the color of blood; the language is colored as well, with a kind of military zeal; and the pilgrim is overwhelmed by the sight of a celestial cross in which Christ is flashing: “’n quella croce lampeggiava Cristo” (Par. 14.104).

The ecstatic language includes the Paradiso’s second set of Cristo rhymes, another Trinitarian occurrence, given that there are three rhymes (the first set was in Paradiso 12, in the life of Dominic) and extends to the end of Paradiso 14. This is the heaven of those who fight for Christ, and we encounter on entering Mars a martial quality that befits its name. To understand what Dante experienced, says the poet, the reader too must pick up his cross and follow Christ: “ma chi prende sua croce e segue Cristo” (But he who takes his cross and follows Christ [Par. 14.106]). This is the Church militant.

There are very few crosses in the Commedia. Now that we have finally come upon a cross, and a context — the heaven of Mars — that genuinely reflects Crusade ideology, we are in a position to reflect upon the gross distortion of the attached image. This is the figure of “Dante” as imagined in the recent video game Inferno: the poet, who was born in Florence in 1265, is here portrayed as a Crusader at the siege of Acre in 1181, with a bloody cross sutured to his flesh.

Return to top

Return to top