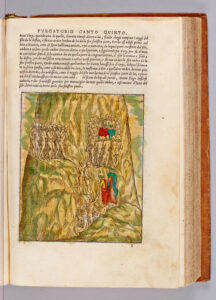

The travelers meet a new group of souls, who are as fast-paced and sharp-edged as the previous group (the lazy) was relaxed and low-key. These new souls seem anxious as they press around Dante, perhaps as a result of their violent deaths and their last-minute barely-achieved-in-time salvations.

One cries out to the others that Dante casts a shadow and that he walks as though alive, but Virgilio, having learned the lesson about no dawdling in purgatory from Cato, forbids Dante to stop and speak to the gawkers. Again, another group notices that Dante’s body blocks the light (he allows “no path for rays of light to cross my body” [Purg. 5.25-26]) and two messengers race over to inquire. Virgilio this time allows an interaction with the souls, in order to confirm what they believe, that they are looking at a living, breathing, fleshly body:

E ’l mio maestro: «Voi potete andarne e ritrarre a color che vi mandaro che ’l corpo di costui è vera carne.» (Purg. 5.31-33)

My master answered them: “You can return and carry this report to those who sent you: in truth, the body of this man is flesh.”

In the verse “’l corpo di costui è vera carne” (Purg. 5.33)—“the body of this man is true flesh”—we find a distillation of the nostalgia for the body that suffuses Ante-Purgatory. The emphasis on the “true flesh” of Dante’s body is particularly apposite for this canto, where three souls will tell of their violent deaths: two in battle, and one at the hands of her husband.

All the souls hanging about on the lower slopes of Mount Purgatory share a still active nostalgia for home: they still yearn for where they lived on earth, the earth that they left behind only quite recently. (We note that the souls we meet in Ante-Purgatory are all roughly contemporaries of Dante; there is no one from antiquity with the exception of the guardian, Cato.) Their nostalgia for home and life on earth is expressed in a continuous interest in the body: our fleshly home while we are alive.

The first to recount his violent death is Iacopo del Cassero, a political figure and warrior, who was assassinated in 1298 by agents of Azzo VIII d’Este, Lord of Ferrara. Iacopo acquired the enmity of Azzo while serving as chief magistrate (podestà) of Bologna, during which time he protected Bologna from Azzo’s expansionist aims.

Azzo subsequently had Iacopo chased down and killed in the territory of Padova, when Iacopo was on his way to serve as podestà in Milano. Iacopo had chosen to go from Fano to Milano by way of Venice precisely to avoid the assassins of Azzo d’ Este, but someone betrayed him.

Assassinated only two years before he meets Dante in Purgatory, Iacopo del Cassero speaks of the “piercing wounds from which there poured the blood where my life lived” (73-74), and describes the pool of blood that forms in the swamp where he dies:

Corsi al palude, e le cannucce e ’l braco m’impigliar sì ch’i’ caddi; e lì vid’io de le mie vene farsi in terra laco. (Purg. 5.82-84)

I hurried to the marsh. The mud, the reeds entangled me; I fell. And there I saw a pool, poured from my veins, form on the ground.

He is saved, and in Purgatory, but Iacopo del Cassero still relives the experience of falling entangled in the mud and reeds of the Paduan swamp, pursued by his successful assassins, and watching the blood pour from his veins onto the ground.

Iacopo’s blood, violently spilled, reminds us of the river of boiling blood, Phlegethon, in which the violent are immersed in Inferno 12. There the tiranni are submerged to their eyebrows, since they exercised violence both with respect to the persons of others and with respect to their possessions. Azzo VIII’s father, Obizzo II d’Este, is immersed in that river, in a passage where Dante suggests that the tyrant was killed by his own son (Inf. 12.110-12). The sympathetic account of Iacopo del Cassero’s bloody death at the hands of Obizzo’s successor is the response of a poet who had written of tiranni that they “plunged their hands in blood and plundering”: “E’ son tiranni / che dier nel sangue e ne l’aver di piglio” (Inf. 12.104-05).

When I read the Commedia, I am always struck by how forcefully Dante communicates historical pain. There is a difference between the metaphoric pain of the afterlife torments and the historical pain communicated by the sad circumstances of Iacopo del Cassero’s death. Dante scholars write about the “sufferings” and “torments” of Hell, but I do not think we respond to those “sufferings” as sufferings. The river of blood of Inferno 12 is not something we feel; it is something we understand. We experience it, in other words, as the metaphor that it is. Our response to Iacopo’s description of watching his blood pool on the ground is very different.

There is certainly physical pain in Hell, but—for me at least—it is not in the contrapassi. It is in the simile that describes the capital punishment meted upon paid assassins, called propagginazione, which consists of burying the criminal head-first in a hole, filling the hole with dirt, and creating death by suffocation (Inferno 19.49-51). Or it is in a form of murder committed on board ships: called mazzerare, this torture consists of putting a living man in a sack with a heavy rock, tying the sack, and throwing it overboard (Inferno 28.80). See the discussion of these forms of historical torture in the Commento on Inferno 27.

The second soul to speak to Dante is Bonconte da Montefeltro, who was a warrior like his father, Guido da Montefeltro (Inferno 27). Bonconte was killed at the battle of Campaldino on 11 June 1289, where he led the Ghibelline cavalry; Dante, who also fought at that battle, was a Guelph and therefore fought on the opposite side. Bonconte, whose body was never found on the battlefield, also recounts his bloody ending, when he was “forato ne la gola, / fuggendo a piede e sanguinando il piano” (my throat was pierced—fleeing on foot and bloodying the plain [Purg. 5.98-99]).

The third soul, the elliptical Pia de’ Tolomei, was killed by her husband. Her story is suppressed, like much domestic violence. She differs in this respect from Francesca da Rimini, who, like Pia, was killed by her husband. Unlike Pia, who offers up so little of her personal story, Francesca tells with gusto her scandalous tale of falling in love with her brother-in-law.

Again, as with Manfredi in Purgatorio 3 (who also died a violent death, at the battle of Benevento), a key theological point is God’s mercy, extended even to those who wait until the “last hour” to “make peace” with Him:

Noi fummo tutti già per forza morti, e peccatori infino a l’ultima ora; quivi lume del ciel ne fece accorti, sì che, pentendo e perdonando, fora di vita uscimmo a Dio pacificati, che del disio di sé veder n’accora. (Purg. 5.52-57)

We all were done to death by violence, and we all sinned until our final hour; then light from Heaven granted understanding, so that, repenting and forgiving, we came forth from life at peace with God, and He instilled in us the longing to see Him.

Bonconte da Montefeltro ends his life with the name of Mary on his lips. How poignant is the comparison with Bonconte’s father, Guido da Montefeltro, who devised a foolproof plan to guarantee salvation, going so far as to become a Franciscan friar. And yet Guido finds himself taken to Hell by a logic-wielding devil at the end of his life. Bonconte gives the opposite account: in the son’s case a devil came for his soul and was rebuffed by an angel. The devil is infuriated that “one little tear”—“una lagrimetta” (Purg. 5.107)—is enough to deprive him of Bonconte’s soul. But so it is.

Return to top

Return to top