Paradiso 2 opens with an address to the readers that may be unique in literary history, in that it is an admonition not to continue reading. Here Dante tells us, his readers, to turn back to our shores rather than to set out on so deep a sea as the text that lies before us. The haunting evocation of a little ship out on the perilous watery deep, alone on the mighty ocean, reverberates to the Commedia’s Ulyssean lexicon, as well of course to the previous canto’s ontological metaphor of the “great sea of being” (Par. 1.113). Dante is transferring the Ulyssean lexicon from the pilgrim to the poet, whose task of recounting the unrecountable is indeed transgressive.

Also very Dantean is the heroic stance of the poet, presented with no ambiguity as the unique and essential conduit to this journey. Putting a “a new spin on the rhetoric of persuasion” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 55), Dante lets his readers know that the task is arduous. If we lose him (“perdendo me”), we will be lost:

O voi che siete in piccioletta barca, desiderosi d’ascoltar, seguiti dietro al mio legno che cantando varca, tornate a riveder li vostri liti: non vi mettete in pelago, ché forse, perdendo me, rimarreste smarriti. (Par. 2.1-6)

O you who are within your little bark, eager to listen, following behind my ship that, singing, crosses to deep seas, turn back to see your shores again: do not attempt to sail the seas I sail; you may, by losing sight of me, be left astray.

As we read, we should work to keep track of the extraordinary repertory of Ovidian characters who populate the Paradiso, like Marsyas and Glaucus in Paradiso 1. Here we don’t get too far into the canto before we arrive at the Argonauts and Jason. Similarly, we need to hang on to the threads of plot-line that the author throws our way. The “story” picks up in Paradiso 2.19, where we learn that Dante and Beatrice are rising; in verse 30 we learn that Dante has been “joined” to the first “star” or heaven:

«Drizza la mente in Dio grata», mi disse, «che n’ha congiunti con la prima stella».(Par. 2.29-30)

“Direct your mind to God in gratefulness,” she said; “He has brought us to the first star.”

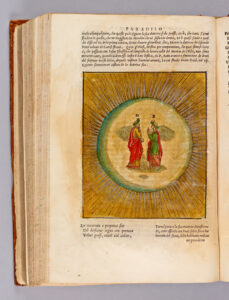

Dante is in the heaven of the moon. The narrator lets us know that the co-penetration of his body (“corpo” in Par. 2.37) with the body of the sphere of the moon is miraculous, and that the question of how two bodies can coexist in the same place at the same time should awaken in us a desire to understand the mystery of Christ, in which our human nature was united with God’s nature:

Per entro sé l’etterna margarita ne ricevette, com’acqua recepe raggio di luce permanendo unita. S’io era corpo, e qui non si concepe com’una dimensione altra patio, ch’esser convien se corpo in corpo repe, accender ne dovrìa più il disio di veder quella essenza in che si vede come nostra natura e Dio s’unio. (Par. 2.34-42)

Into itself, the everlasting pearl received us, just as water will accept a ray of light and yet remain intact. If I was body (and on earth we can not see how things material can share one space—the case, when body enters body), then should our longing be still more inflamed to see that Essence in which we discern how God and human nature were made one.

The co-penetration of bodies, something that cannot happen on earth, in space-time as we know it, can happen in the alternate dimension of reality that Dante has now entered. How can the pilgrim cease to be “other” and become “one” with the moon while both he and it remain themselves? I analyze the rhetorical tropes that Dante uses in the above passage in The Undivine Comedy:

In this passage Dante renders the paradox: difference exists — “una,” “altra,” “corpo,” “corpo” — but it is embraced and resolved into an all-encompassing unity; “unita” introduces the conundrum, while “s’unio” completes it. The verbal repetition, in this case of corpo, later on in the canto of luce (“da luce a luce” in verse 145), initiates a technique that the poet will use frequently in the third canticle, as a way of signifying the paradox of the thing that both is itself and is the other. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 178)

Dante-pilgrim poses a question about the cause of the “dark spots” on the surface of the moon, referring to the popular legend of Cain’s imprisonment there:

che son li segni bui di questo corpo, che là giuso in terra fan di Cain favoleggiare altrui? (Par. 2.49-51)

What are the dark marks on this planet’s body, that there below, on earth, have made men tell the tale of Cain?

This is an issue that Dante cares deeply about, and which he had tackled previously. He had addressed this same question in his philosophical treatise Convivio (circa 1304-1306), where he had espoused the very solution that Beatrice will now discard as mistaken. In effect, then, Paradiso 2 demonstrates the existence of three levels of explanation for the problem of moon spots, and, by extrapolation, for other problems as well: the popular and legendary explanation regarding Cain; the materialist explanation of the Convivio; and the metaphysical explanation of the Commedia.

The question offers the opportunity to “translate” a problem from the material/ corporeal to the immaterial/metaphysical. The “wrong” answer that he had once accepted as correct in the Convivio, and which is based on a material understanding of the substances and issues involved, is that the dark spots are caused by one substance that is disposed in such a way that it is thick in some places and thin in others: “i corpi rari e densi” (Par. 2.60).

To show why the above answer is wrong, Dante suddenly transitions from the moon to what he will explain is a version of the same problem, but in a different location. This version of the problem requires us to transfer to the eighth heaven. This huge jump in the presentation of the argument on moon spots, which suddenly transitions from a discussion of the heaven of the moon to a discussion of the eighth heaven, is the key move that the reader must grasp. Once we realize that Dante has made this huge rhetorical leap in his argument, then his explanation falls nicely into place.

I have mentioned that the Paradiso will often seek to provide its answers from first principles, and this is a good example. Rather than answer the specific query about the moon’s dark spots, Beatrice tackles the problem of difference itself. To do that, she makes the leap to the eighth sphere, because the eighth heaven is the heaven where difference itself originates.

Beatrice explains that the eighth heaven, also known as the heaven of the fixed stars, is the generator of difference in the universe. Each of the different stars in the “spera ottava” (Par. 2.64) embodies substantial difference, difference in essence or form (Par. 2.64-66). The words “essence,” “substance,” and “form” are synonyms in Dante’s Aristotelian usage. In other words, the difference embodied by the different stars of the eighth sphere is not merely apparent (and material), but essential (and metaphysical)

If, as the pilgrim had suggested, difference were but one material substance differently disposed, thicker in some places and thinner in others, then there would be only one substance, one essence, shared by all the stars of the eighth sphere, and that one essence would be differentially distributed, more or less in different locations:

Se raro e denso ciò facesser tanto, una sola virtù sarebbe in tutti, più e men distributa e altrettanto. (Par. 2.67-69)

If rarity and density alone caused this, then all the stars would share one power distributed in lesser, greater, or in equal force.

If “una sola virtù” (Par. 2.68) were shared by all the stars in the heaven of the fixed stars, then all the stars would be essentially the same, the same in essence, just thicker in some places and thinner in others. If all the stars in the heaven of the fixed stars were the same in essence, there would be no true (metaphysical) difference in the cosmos.

The whole point of this exercise is to make the opposite point: that difference is metaphysically real, that it is an “essential” principle of God’s creation. With the term “essential principle” I am replicating Dante’s language: “princìpi formali” in Par. 2.71 and “formal principio” in Par. 2.147. This use of the adjective “formale” to mean “essential” picks up on the word “forma” in Paradiso 1.104 and anticipates “formale” in Paradiso 3.79.

The difference that we see in the universe must be rooted in different essences, different formal principles:

Virtù diverse esser convegnon frutti di princìpi formali, e quei, for ch’uno, seguiterìeno a tua ragion distrutti. (Par. 2.70-72)

But different powers must be fruits of different formal principles; were you correct, one only would be left, the rest destroyed.

Difference must exist as an ontological principle, for it is an integral part of God’s creation. Indeed, God’s creation is the making of difference. In The Undivine Comedy I cite the Thomas’s dictum, “distinctio et multitudo rerum est a Deo”:

The one made the many: “distinctio et multitudo rerum est a Deo” — “the difference and multiplicity of things come from God” (ST 1a.47.1). In the act that we call creation, God made difference, in Thomas’s words, “so that his goodness might be communicated to creatures and re-enacted through them” (ibid; Blackfriars 1967, 8:95). (The Undivine Comedy, p. 174)

This idea is set forth in the great creation discourse that starts in verse 112, whose goal is to emphasize the difference that creates the universe. In this speech Dante starts at the top, in the “heaven of divine peace” — “ciel de la divina pace” (Par. 2.112) — which is the Empyrean heaven where God resides, and from there he makes his way down through the various heavens: to the ninth heaven or Primum Mobile (first moving heaven) in Paradiso 2.113-14, thence to the eighth heaven or heaven of the fixed stars (Par. 2.115-17), and so on down through the lower heavens. At all points Dante is emphasizing the creation of difference: difference as the essential manifestation of God’s creative impulse.

The Emprean heaven is the “heaven of divine peace” (Par. 2.112); it does not move, because it is the transcendent principle, it is the Unmoved Mover. Within the Empyrean revolves the Primo Mobile or First Mover, and here the actualization of being occurs: “Dentro dal ciel de la divina pace/ si gira un corpo ne la cui virtute / l’esser di tutto suo contento giace” (Within the heaven of the godly peace revolves a body in whose power lies the being of all things that it enfolds [Par. 2.112-14]). The heaven that follows — the eighth heaven or heaven of the fixed stars — divides and differentiates the being that is actuated in the Primo Mobile: “Lo ciel seguente, c’ha tante vedute, / quell’ esser parte per diverse essenze, / da lui distratte e da lui contenute” (The sphere that follows, where so much is shown, to varied essences bestows that being, to stars distinct and yet contained in it [Par. 2.115-17]).

The eighth heaven thus initiates the division of the One into the Many that will be further carried out in the seven successive heavens: “Questi organi del mondo così vanno, / come tu vedi omai, di grado in grado, / che di sù prendono e di sotto fanno” (So do these organs of the universe proceed, as you now see, from stage to stage, receiving from above and acting downward [Par. 2.121-23]).

Beatrice’s speeches of Paradiso 1 and 2 — both devoted to illuminating the order of the universe — are complementary, book-ends as it were. The speech on the order of the universe in Paradiso 1 illustrates all of creation returning to the One, whereas the speech on the order of the universe in Paradiso 2 illustrates the One creating the many that will eventually return to the One. The heavens first actualize being and subsequently differentiate it. The process of differentiation begins in the eighth heaven and continues down, ultimately manifesting itself in the dark spots on the moon, the spots that cause the unlearned to speak of Cain.

Return to top

Return to top