- intratextual references to earlier passages in Inferno: Capaneus in Inferno 14 and Centaurs in Inferno 12

- the “Geryon principle” (see Inferno 25.46-48)

- metamorphosis: a process through which essence changes its outward shape

- metamorphosis in this bolgia is used as a means of perverting the most fundamental Christian mysteries and the most natural/biological events constitutive of self: sex and birth

- Metamorphosis 2: in malo Copulation, performed as male-on-male (serpent-on-male) rape, which is also an in malo Incarnation, whereby the mystery of Two Who Become One degrades into Two Who Become No One

- the relationship of the above to the “bi-form” griffin/Christ of Purgatorio 32

- Metamorphosis 3: in malo Embryology, which is also in malo Transubstantiation, whereby Two Exchange Shape & Substance

- this is the negative variant of embryology in Purgatorio 25

- the relevance of the stories of Arethusa and Salmacis from Metamorphoses, stories of rape culture and loss of self: “et se mihi misceat” (that he might mingle with me [Metam. 5.638])

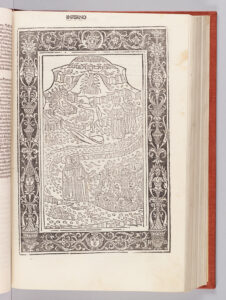

[1] Inferno 25 is the second canto devoted to the seventh bolgia, the home of the fraudulent thieves, all Florentine Black Guelphs. It features changes of shape that are even more spectacular and grotesque than those in Inferno 24.

[2] The beginning sequence of Inferno 25 functions as a conclusion to Inferno 24, which ended with Vanni Fucci’s lacerating political prophecy. Now the thief engages in extreme defiance of God, with his fists raised in an obscene gesture and his speech violent — “Togli, Dio, ch’a te le squadro!” (Take that, God! God; I square them off for you! [Inf. 25.3]) — until he is silenced by the serpents. As a result of the silencing of Vanni Fucci the serpents become “Dante’s friends”: “Da indi in qua mi fuor le serpi amiche” (From that time on, those serpents were my friends [Inf. 25.4]). Given that the serpents will be revealed to be sinners — in this bolgia sinners alternate between their original human shape and the shapes of many and diverse kinds of serpents — the thought of them as “friends” is quite unsettling.

[3] Moreover, the idea of the serpents as friends sets the stage for the socially macabre aspect of this bolgia, part of the dramatic unfolding of Inferno 25: since the serpents are sinners in serpent form, the sinners are attacked by their own erstwhile “friends” and comrades.

[4] There is also a fascinating intratextual component to the opening sequence of Inferno 25. Here Dante employs one part of his text to buttress another part of his text, using his possible world in all its aspects as guarantor of the truth of his account. In Inferno 25, in order to underscore the arrogance of the thief Vanni Fucci, Dante compares him to Capaneus, one of the seven against Thebes and the featured blasphemer of Inferno 14:

Per tutt’ i cerchi de lo ’nferno scuri non vidi spirto in Dio tanto superbo, non quel che cadde a Tebe giù da’ muri. (Inf. 25.13-15)

Throughout the shadowed circles of deep Hell, I saw no soul against God so rebel, not even he who fell from Theban walls.

[5] In all of Hell, Dante says, he saw no soul so arrogant — “tanto superbo” (Inf. 25.14) — as Vanni Fucci, not even the one who fell from the walls of Thebes. The periphrasis for Capaneus, here called “quel che cadde a Tebe giù da’ muri” (he who fell from Theban walls [Inf. 25.15]), evokes the inevitable fall of those who blaspheme against the Highest Power, be that power called “Giove” by Capaneus (Inf. 14.52) or “Dio” by Vanni Fucci (Inf. 25.3). The adjective “superbo” in Inferno 25.14 echoes the noun “superbia” from Virgilio’s impassioned attack on Capaneo in Inferno 14:

O Capaneo, in ciò che non s’ammorza la tua superbia, se’ tu più punito; nullo martiro, fuor che la tua rabbia, sarebbe al tuo furor dolor compito. (Inf. 14.63-6)

O Capaneus, for your arrogance that is not quenched, you’re punished all the more no torture other than your own madness could offer pain enough to match your wrath.

[6] This passage is instructive in terms of the ongoing distinction that Dante establishes between the actual sins that — because never repented — place the sinners in Hell, and the underlying vice that originally prompts a given soul to sin. In the case of Vanni Fucci, as with Capaneo, the underlying vice is superbia, pride. In Capaneo’s case the actual sin is blasphemy, while in Vanni Fucci’s case the actual sin is theft, but in both cases the underlying vice is pride: pride, left unchecked, drove both souls to sin. I discuss the distinction between sin and vice for the first time in the Commento on Inferno 6.

[7] A second intratextual moment occurs slightly further on in Inferno 25, when the author explains why the centaur Cacus does not “ride the same road as his brothers”: “Non va co’ suoi fratei per un cammino” [Inf. 25.28]). In other words, Cacus does not reside with the other centaurs in the first ring of the seventh circle (Inferno 12), the ring that contains the violent against others, in both their selves and in their possessions. As I discussed in the Commento on Inferno 24, Dante uses the reference to the centaurs in Inferno 12 to construct his distinction between violent robbers and fraudulent thieves.

[8] Ultimately, these intratextual moments are always in service of the Commedia’s truth claims: the text buttresses the text, the fiction supports the credibility of the fiction. And indeed the author will shortly apply the rhetorical trope that I call the “Geryon principle” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 60), whereby the more fantastical and in-credible the “maraviglia” that the narrator is called upon to describe, the more he asserts he is telling the truth, using the verb “vidi” (I saw):

Se tu se’ or, lettore, a creder lento ciò ch’io dirò, non sarà maraviglia, ché io che ’l vidi, a pena il mi consento. (Inf. 25.46-48)

If, reader, you are slow now to believe what I shall tell, that is no cause for wonder, for I who saw it hardly can accept it.

[9] For Dante’s construction of his visionary authority through techniques like the “Geryon principle” see The Undivine Comedy, passim; for the first time that Dante applies this trope, in Inferno 16, see pp. 60 and 90.

* * *

[10] As discussed in the Commento on Inferno 24, the seventh bolgia features metamorphoses: processes through which essence changes its outward shape. In Inferno 24 serpents bind one of the sinners, Vanni Fucci, who burns and goes up in smoke, becoming a pile of ash, and then “is reborn” (“rinasce” [Inf. 24.107]) and returns to human form. This metamorphosis is a perverse and in malo version of death and resurrection, and indeed the image of the phoenix (featured in Inferno 24.106-8) was used in Christian iconography to represent the Resurrection of Christ. The perversion of fundamental Christian mysteries continues in Inferno 25, where there are two further metamorphoses.

[11] In the seventh bolgia, Dante uses the concept of metamorphosis, a process through which essence changes its outward shape, as a means of perverting the most fundamental Christian mysteries. He simultaneously perverts the most natural and biological events constitutive of self: sex and birth.

[12] In this way, as he destroys the very foundations of selfhood, Dante indicates that Christianity and its core mysteries support the constitution of the self.

[13] The negation of the constitution of selfhood in the seventh bolgia also has a social dimension. Dante carefully scripts this bolgia in order to deny the sinners their names. Their names are withheld until after they have undergone a change in shape. These souls do not receive that most fundamental marker of selfhood and historicity, their names.

[14] More precisely, these souls do not receive their names until they are no longer the selves to which their names belong. Or better, they receive their names when they no longer appear to be the selves to which their names belong. As we stipulated previously, in the Commento on Inferno 24 (and indeed, as discussed also in the Commento on Inferno 13), Dante’s point (like Ovid’s) is that the self remains, indelible for all eternity, despite being perversely violated and transformed.

[15] In verse 35 of Inferno 25, Dante first tells us that three spirits have appeared. They are directly below Dante and Virgilio, who look down into the seventh bolgia: “e tre spiriti venner sotto noi” (just beneath our ledge, three souls arrived [Inf. 25.35]). From that time on the narrator goes to extraordinary lengths to withhold the names of the three sinners. He never vouchsafes their last names, and we learn that they are Florentines only in the opening apostrophe of Inferno 26.

[16] Social ties are evoked in order to be monstrously violated. Thus, it happens that one sinner names another, an event that Dante introduces with the ambiguous pronouns typical of this canto: “l’un nomar un altro convenette” (one of them called out the other’s name [Inf. 25.42]). The sinner who speaks is asking his comrades where another sinner, Cianfa, has gotten to: “Cianfa dove fia rimaso?” (Where was Cianfa left behind? [Inf. 25.43]). This is such a simple question, the sort that occurs in social units all the time, many times a day. But here the question hides a sinister reality: in this bolgia it behooves one to keep tabs on one’s comrades, for a “friend” who disappears from sight may well resurface as a serpent. And, in fact, the simple “Where has Cianfa gotten to?” heralds a sinister outcome, for the six-footed snake of verse 50 will turn out to be none other than Cianfa.

[17] We learn the identity of the sinner attacked by the serpent of verse 50 — as noted, the serpent is his comrade, Cianfa, now in serpent form — only in the moment of his grotesque transformation: “Omè, Agnel, come ti muti!” (Ah me, Agnello, how you change! [Inf. 25.68]). Buoso, too, is named only after he has become a snake, his name uttered venomously and vindictively by the newly-formed man who has exchanged forms with him: “I’ vo’ che Buoso corra, / com’ho fatt’ io, carpon per questo calle (I want Buoso to run / on all fours down this road, as I have done [Inf. 25.140-41]). Puccio Sciancato is named in verse 148, the only one of the three original souls not to have been changed in the course of the pilgrim’s viewing of this bolgia: “ed era quel che sol, di tre compagni / che venner prima, non era mutato” (the only soul who’d not been changed among / the three companions we had met at first [Inf. 25.149-50]). The last verse of Inferno 25 is devoted to indicating the identity of the final soul, without however stating his name: the opaque apostrophe about making Gaville weep will have to suffice to identify Guercio de’ Cavalcanti.

[18] The social community that forms in the seventh bolgia is decidedly more sinister than, for instance, the community that we glimpse in the fifth bolgia. There Ciampolo offers to betray his fellow grafters to the Malebranche, to use their secret signal to summon his comrades from the safety of the pitch (Inferno 22.103-05) and thereby leave them open to the attacks of the devils. In the seventh bolgia, in contrast, the mediation of violent devils is no longer necessary: one thief directly attacks the other, inflicting on his comrade the transformative abuse that he himself has previously suffered.

[19] When the thieves are in their human shapes, they are victims of their comrades in their serpent shapes. When they are in their serpent shapes, the previous victims are now perpetrators, intent upon victimizing their fellow thieves.

[20] It is difficult to ascertain who is who as we read the canto, for Dante systematically uses pronouns instead of names and blurs identities as he recounts the metamorphoses. Only by careful tracking of the pronouns can we reconstruct a story-line in which the protagonists have names. By giving the last two characters their names only in the very last verses of Inferno 25, only as the text is about to leave them behind, Dante reinforces the loss of selfhood and identity that this bolgia of in malo transformation explores.

[21] In effect, Dante tells the story of the thieves in such a way that each is at risk of becoming “no one” during the course of the action. Analogously, in Inferno 25’s first metamorphosis (the second metamorphosis of the bolgia), a “perverse image” is formed that is “due e nessun”: “two and no one” (Inf. 25.77).

Metamorphosis 2

Two Become One ⇒ Two Become No One:

in malo Copulation and Incarnation

[22] In the first metamorphosis of Inferno 25, a six-footed serpent (the missing Cianfa) takes hold of a sinner and intertwines its body with the man’s body, in a grotesque replay of copulation. Latin “copula” means “bond” or “tie”; all through this bolgia the serpents are seen tying and binding the sinners in their disgusting coils.

[23] Dante here scripts what he dramatizes as obscene sexual intercourse, as obscene copulation. In fact, given the violence of the snake’s assault, this is not sexual intercourse but rape, a violent and degrading physical intimacy imposed by one being upon another.

[24] What occurs in this bolgia is male-on-male — serpent-on-male — rape. The moments of contact, as described in the three metamorphoses, are all violent and all involve compulsion:

- Metamorphosis 1, Inferno 24.97-99: “Ed ecco a un ch’era da nostra proda, / s’avventò un serpente che ’l trafisse / là dove ’l collo a le spalle s’annoda” (And — there! — a serpent sprang with force at one / who stood upon our shore, transfixing him / just where the neck and shoulders form a knot)

- Metamorphosis 2, Inferno 25.49-51: “Com’io tenea levate in lor le ciglia, / e un serpente con sei piè si lancia / dinanzi a l’uno, e tutto a lui s’appiglia” (As I kept my eyes fixed upon those sinners, / a serpent with six feet springs out against / one of the three, and clutches him completely)

- Metamorphosis 3, Inferno 25.83-86: “un serpentello acceso, / livido e nero come gran di pepe; / e quella parte onde prima è preso / nostro alimento, a l’un di lor trafisse” (a blazing little serpent / moving against the bellies of the other two, / as black and livid as a peppercorn. / Attacking one of therm, it pierced right through / the part where we first take our nourishment)

[25] The male-on-male rapes of Inferno 25 (informed by Ovidian heterosexual rapes, as discussed below) give us some insight into what Dante could have done, but most emphatically does not do, in his treatment of sodomy in Inferno 15 and 16. The violent sexual assaults of Inferno 24 and 25, all occurring between men in the forms of men and men in the forms of snakes (men in the forms of phalluses!), show us that Dante is able to conjure graphically sexualized language and comportment in an all-male context. This is precisely the language and imagery that he avoids in Inferno 15-16.

[26] In the seventh bolgia, Dante is depicting the violation of one being by another through an obscene and violent copulation. Stripped of the violence and perversion of this bolgia, copulation is the process whereby two differentiated substances become one through sexual intercourse, while simultaneously remaining two.

[27] If we were to exalt this biological process, the process whereby two become one would be known (as in fact it is, through various media, poetic and philosophical) by the name love. Dante in his canzone Doglia mi reca specifically defines love as the power that can make two essences into one: “di due poter un fare” (of two, [Love has] the power to make one [Doglia mi reca, 14]).

[28] The power to make two into one finds expression in the “rhetorical copulation” that Dante invents in the heaven of Venus (Dante’s Poets, p. 116), where the pronouns “I” and “you” metamorphose into verbs that perform the copulation of the Self and the Other. In the stunning verse “s’io m’intuassi, come tu t’inmii” (if I could in-you myself, as you in-me yourself [Par. 9.81]), the pronouns “io” and “tu” are agents of a transfigured and copulated ontology. It is worth noting that Dante-pilgrim speaks those words to his friend Carlo Martello; in other words, this “rhetorical copulation” of the heaven of Venus does not shy away from male-on-male “intercourse”. For more on this topic, as it relates to the subset of love that we call friendship, see my essay “Amicus eius: Dante and the Semantics of Friendship”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

[29] The process whereby two differentiated substances become one, while simultaneously remaining two, is also applicable, mutatis mutandis, to the idea of Christ. The doctrine of the Incarnation is that Christ is both two and one: fully God and fully human. This is the penultimate mystery of Paradiso 33, dramatized as the second of the three circles at the end of the Commedia: the second circle is the one on which a human image can be individuated, despite being painted in same color as the circle itself. The fact that the human image can be seen is a way of communicating that the image is differentiated, that there are indeed two components to Christ’s nature; the fact that the human image is painted in the same color as the circle itself is a way of communicating that Christ’s nature is undifferentiated, that it is one.

[30] As the first metamorphosis of bolgia seven (in Inferno 24) pantomimes the Resurrection, so the second metamorphosis of bolgia seven pantomimes the Incarnation. Dante’s dramatizations take the form of infernal perversions. We note that “perversion” is Dante’s category, explicitly stated with the label “imagine perversa” (perverse image [Inf. 25.77]), with which he defines the product of the second metamorphosis.

[31] Dante’s second metamorphosis is constructed as an in malo violation of principles of unity, of the binding of two into one, principles that he parses into three different categories:

- Sexual Unity: in malo perversion of copulation

- Psychological Unity: in malo perversion of love

- Metaphysical Unity: in malo perversion of Christ’s Incarnation

[32] In the course of dramatizing the perversion and degradation of the idea of “two becoming one”, Dante produces two formulas regarding the two beings — man and snake — and what they become. The first formula is “neither two nor one”: “Vedi che già non se’ né due né uno” (you are already neither two nor one [Inf. 25.69]). The second formula is “two and no one” in “due e nessun l’imagine perversa / parea” (the perverse image seemed two and no one [Inf. 25.77-78]):

Ogne primaio aspetto ivi era casso: due e nessun l’imagine perversa parea; e tal sen gio con lento passo. (Inf. 25.76-78)

And every former shape was canceled there: that perverse image seemed to share in both — and none; and so, and slowly, it moved on.

[33] The phrase “two and no one” seems to indicate that the monstrous hybrid produced by this metamorphosis is not a new being, but a new non-being and that Dante has set himself the challenge of representing the creation of that which is not. But at the same time his language suggests that it is not possible to create non-being, for the hybrid “imagine perversa” comes into being and exists. In the Appendix below the reader can explore some of the philosophical problems that are raised by Dante’s formulations, in the light of modern philosophy of mind.

[34] In Inferno 25 Dante dramatizes a perversion of the Incarnation. The imagine perversa is a perversion of the fundamental Christian doctrine of Christ’s dual nature, as evoked through the figure of the griffin in the Earthly Paradise. The griffin is “biforme”, literally “bi-form”, possessing two forms: “la biforme fera” (the two-form animal [Purg. 32.96]). The word “biforme”, used uniquely for the griffin/Christ and a hapax in the Commedia, is the in bono Christological variant of the in malo dual hybrids we have seen throughout Inferno: the Centaurs, for instance, possess two forms. Most importantly, the griffin is the in bono reply to the infernal metamorphosis in which a sinner becomes not “two-form” but “no-form”: a kind of existential black hole. Moreover, as I discuss below in the last section of this commentary, the word “biforme” in Purgatorio 32 echoes “forma duplex” from a key Ovidian intertext of these metamorphoses. In the dark Ovidian account of Salmacis’ rape of Hermaphroditus, the two protagonists become a new bi-form, which seems neither and both:

nec duo sunt et forma duplex, nec femina dici nec puer ut possit, neutrumque et utrumque videntur. (Metam. 4.378-79)

No longer two but one — although biform: one could have that shape a woman or a boy: for it seemed neither and it seemed both. (Mandelbaum trans.)

Metamorphosis 3

Two Exchange Shape & Substance:

in malo Embryology and Transubstantiation

[35] In the third metamorphosis of the seventh bolgia (the second of Inferno 25), a serpent and a man exchange shapes. This double metamorphosis figures an obscene — because violent and perverse — embryology. The process as described here is the in malo variant of the generation of the fetus as described in the great discourse on embryology and differentiation of Purgatorio 25.

[36] The attacking “serpentello” of verse 83 pierces a sinner through the navel, described in embryological terms as “the part where we first take our nourishment”: “quella parte onde prima è preso / nostro alimento” (Inf. 25.85-86). It fixes its gaze on the sinner, catching him in a hypnotic snare from which there is no escape: “Elli ’l serpente e quei lui riguardava” (The serpent stared at him, he at the serpent [Inf. 25.91]). Enveloped in a noxious smoke that emanates from the mouth of the attacking snake and from the “wound” in the navel of the thief, and that forms a kind of amniotic sack around the two conjoined figures, a long and revolting process unfolds: body part for body part is exchanged, in a precise and graphic transmutation of man into serpent and serpent into man.

[37] Embryology and birth — the generation of new life — suggest that Dante has shifted from metamorphosis to metousiosis (μετουσίωσις), the Greek term that refers to a change not of shape alone but also of essence or inner reality. Greek metousiosis is the equivalent of Latin transsubstantiatio or transubstantiation, which is the technical term used by theologians for the change by which the bread and the wine used in the sacrament of the Eucharist become in actual reality the body and blood of Christ: “vere, realiter ac substantialiter” (truly, really, and substantially). Not a figure or symbol of Christ’s body and blood, nor merely the outward shape or external form of Christ’s body and blood: the bread and wine become the true substance and reality of Christ’s body and blood. In other words, the substance or essence of the being is changed.

[38] Dante, I suggest, offers here an in malo version of transubstantiation or metousiosis. In this process, not only shape is changed, but essence, indicated by the Aristotelian word “forma” which in scholastic Latin means “essence”:

ché due nature mai a fronte a fronte non trasmutò sì ch’amendue le forme a cambiar lor matera fosser pronte. (Inf. 25.100-2)

He [Ovid] never did transmute two natures, face to face, so that both forms were ready to exchange their matter.

[39] In this creation of new — but horrific — life, all the principles of divine creation are violated. In Inferno 25, creation is an act of violent depredation: of one creature imposed upon another. It is not God’s act of Creation as a manifestation of His infinite love and generosity, as described in Paradiso 7, Paradiso 13, and Paradiso 29. Nor is it the love of the mother for the infant.

[40] The love that is violated in this perverse embryology is God’s love for His Creation and also the love of a mother for the child that gestates within her, the love for the embryo that is created within Self but that differentiates into an Other. Given the hypnotic gaze of the serpentello, the words of the psychologist Daniel Stern about the extraordinary and anomalous gaze exchanged between mother and infant are highly relevant:

The first rule in our culture is that two people do not remain gazing into each other’s eyes (mutual gaze) for long. Mutual gaze is a potent interpersonal event which greatly increases general arousal and evokes strong feelings and potential actions of some kind, depending on the interactants and the situation. It rarely lasts more than several seconds. In fact, two people do not gaze into each other’s eyes without speech for over ten or so seconds unless they are going to fight or make love or already are. Not so with mother and infant. They can remain locked in mutual gaze for thirty seconds or more. (Daniel N. Stern, The First Relationship: Infant and Mother)

[41] In the third metamorphosis we witness the perverse creation of new unities. We can think in terms of the same in malo violation of principles of unity that we saw in the previous metamorphosis, parsed into the same three categories:

- Biological Unity: in malo perversion of embryology, gestation, and birth

- Psychological Unity: in malo perversion of maternal love

- Metaphysical Unity: in malo perversion of the Christian doctrine of Transubstantiation

[42] The verses that detail this obscene embryology have a weird plasticity about them, as though an unseen hand were sculpting the two shapes that emerge:

Quel ch’era dritto, il trasse ver’ le tempie, e di troppa matera ch’ in là venne uscir li orecchi de le gote scempie; ciò che non corse in dietro e si ritenne di quel soverchio, fé naso a la faccia e le labbra ingrossò quanto convenne. (Inf. 25.124-29)

He who stood up drew his back toward the temples, and from the excess matter growing there came ears upon the cheeks that had been bare; whatever had not been pulled back but kept, superfluous, then made his face a nose and thickened out his lips appropriately.

[43] As we read the passage that extends 33 verses (from verse 103 to verse 135), we feel that we are receiving the intense and precise instructions of a demiurge, of a fabbro, of a sculptor of living shapes. If we were to start with two clay figures in front of us, one a serpent and the other a man, we could — I believe — follow the poet’s detailed instructions so that, step by step, the serpent would change into a man and the man would change into a serpent.

[44] This 33-verse description is the reason, Dante says, that he can claim to have done what Ovid never did. For, he says, Ovid in his metamorphoses never demonstrated how two beings simultaneously — “a fronte a fronte” (face to face) — exchange shape and substance (forma):

ché due nature mai a fronte a fronte non trasmutò sì ch’amendue le forme a cambiar lor matera fosser pronte. (Inf. 25.100-2)

He [Ovid] never did transmute two natures, face to face, so that both forms were ready to exchange their matter.

[45] In verses 103 to 135 Dante does precisely what he describes above: he puts the two shapes “a fronte a fronte” and — verse by verse, body part by body part — he transmutes them, changing serpent to man and man to serpent. He culminates with the heads of both creatures, as the man’s lips thicken and the serpent’s tongue becomes unforked, giving it the human gift par excellence, that of speech.

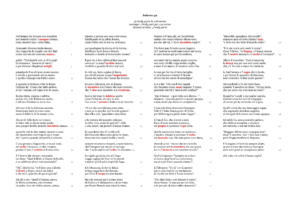

[46] Not surprisingly, Dante has concentrated here the greatest number of body parts in the Inferno. In the chart below, compiled by Grace Delmolino, Inferno 25 (top right) emerges as the canto featuring the densest saturation of words designating body parts. A total of 63 body parts are named in this canto (followed by 41 in Inferno 28, 30 in Inferno 30, and 26 in Inferno 20). This linguistic saturation occurs because Inferno 25 describes a birth — nothing less than a revolting, monstrous birth.

* * *

[47] In the seventh bolgia Dante boasts that he has surpassed both Lucan and Ovid, the classical poets who supply the store of metamorphoses on which he draws. In commanding Lucan and Ovid to be silent, since he has surpassed them, Dante calls out specific metamorphoses recounted by the earlier poets. With respect to Ovid, these are the metamorphoses of Cadmus and Arethusa: “Taccia di Cadmo e d’Aretusa Ovidio” (Let Ovid be silent, where he tells of Cadmus and Arethusa [Inf. 25.97]).

[48] The Ovidian metamorphosis of Cadmus recounts his transformation, with his wife Harmonia, into two loving snakes. Quite the opposite of the violent assaults of Inferno 25, Harmonia desires Cadmus’s touch, even after he is a snake, and asks to join him in serpent conjugality (see Metam. 4.563-603). Serving as a foil to the grotesque copulations of Inferno 25, the Ovidian story of Cadmus and Harmonia depicts two snakes loving each other, in sharp contrast to the terror-filled depredations of the seventh bolgia. Moreover, the reference to Ovid’s Cadmus evokes “li duo serpenti avvolti” (the two entwining serpents [Inf. 20.44]) of the description of Tiresias in Inferno 20.40-45. (See the Appendix on Tiresias in the Commento on Inferno 20.)

[49] The other Ovidian myth evoked in the verse “Taccia di Cadmo e d’Aretusa Ovidio” (Inf. 25.97) is the story of the nymph Arethusa, which is an account of a rape. The nymph runs and runs from the pursuit of the river god Alpheus, who has taken on the form of a man (Metam. 5.572-641). Her struggle is vain, for she turns into a fountain and he resumes his river form in order to merge with her. Struggle as she might to remain individuated, she ends up merged with him as liquid:

sed enim cognoscit amatas amnis aquas positoque viri, quod sumpserat, ore vertitur in proprias, et se mihi misceat, undas. (Metam. 5.636-38)

But in those waters, he, the river-god Alpheus, recognizes me, his love; leaving the likeness he had worn, he once again takes on his river form, that he might mingle with me. (Mandelbaum trans.)

[50] The Latin phrase “et se mihi misceat” (638) — “that he might mingle with me” — is programmatic with respect to the first of the two metamorphoses recounted in Inferno 25.

[51] Similarly programmatic and Ovidian is the reference to fiercely entwining ivy in Inferno 25.58-60, an image that summons another tale of violent sexual assault, that of the nymph Salmacis on the boy Hermaphroditus, as recounted in Metamorphoses 4.274-316. Dante found in Ovid’s account of Salmacis’ rape of Hermaphroditus much to inspire the language and terror of Inferno 25.

[52] Ovid compares Salmacis to an entwining serpent, to ivy as it coils around tree trunks, to an octopus who holds its enemy in its tentacles:

denique nitentem contra elabique volentem inplicat ut serpens, quam regia sustinet ales sublimemque rapit: pendens caput illa pedesque adligat et cauda spatiantes inplicat alas; utve solent hederae longos intexere truncos, utque sub aequoribus deprensum polypus hostem continet ex omni dimissis parte flagellis. (Metam. 4.361-67)

At last, although he strives to slip away, he’s caught, he’s lost; she twines around him like a serpent who’s been snatched and carried upward by the king of birds — and even as the snake hangs from his claws, she wraps her coils around his head and feet, and with her tail, entwines his outspread wings; or like the ivy as it coils around enormous tree trunks; or the octopus that holds its enemy beneath the sea with tentacles, whose vise is tight. (Mandelbaum translation)

[53] Ultimately, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus merge into one new being:

vota suos habuere deos; nam mixta duorum corpora iunguntur, faciesque inducitur illis una. (Metam. 4.373-75)

Her plea is heard; the gods consent; they merge the twining bodies; and the two become one body with a single face and form. (Mandelbaum trans.)

[54] The two become one, a concept Ovid restates in more sinister fashion at the end of the account, noting that the new duplex being is neither the one nor the other:

nec duo sunt et forma duplex, nec femina dici nec puer ut possit, neutrumque et utrumque videntur. (Metam. 4:377-79)

so were these bodies that had joined no longer two but one—although biform: one could have that shape a woman or a boy: for it seemed neither and it seemed both. (Mandelbaum trans.)

[55] The Latin “neutrumque et utrumque videntur” (it seemed neither and it seemed both) is carried over into Dante’s “due e nessun / l’imagine perversa parea” (Inf. 25.77-78).

[56] Ultimately, from Dante’s point of view, the superiority of his metamorphoses to Lucan’s and Ovid’s derives from that which they pervert: not only the most natural and biological events constitutive of self — sex and birth — but the Christian doctrines of the Resurrection, the Incarnation, and the Transubstantiation. As negative versions of Christian mysteries, these metamorphoses perforce, from Dante’s perspective, resonate with a power not available to their classical counterparts. At the same time, Dante continues to find in Ovid’s treatment of sexuality, embodiment, and even violent sexual assault a key to the highest mysteries: for Ovid is the poet whose transformations inform the Paradiso.

Appendix

A Philosopher’s Note

[57] Here follows the fascinating response of a contemporary philosopher of mind to Dante’s first metamorphosis in Inferno 25, the metamorphosis that results in “two and no one”. The author of the below remarks is Dr. Nemira Gasiunas, who recieved her Ph.D. in Philosophy from Columbia University in 2019. Dr. Gasiunas’ dissertation is on the part-whole structure of mental representation. Although distinct from the traditional understanding of the problem of unities (which belongs to the domain of metaphysics rather than to that of philosophy of mind), the topics converge in so far as they are both informed by foundational questions about mereology; that is, the study of the relationship between wholes and their parts.

[58] Nemira Gasiunas’ comments on the metamorphoses of Inferno 25, cited below, illuminate how the issues that Dante is dealing with here are fundamental to philosophy and continue to invite exploration and analysis. And, indeed, her comments also suggest how Dante’s formulations can be challenged.

When Dante describes the perverse intermingling of the snake and the sinner, he describes it first as “two and no-one”, and later as “neither two nor one”. But these are two quite different states of affairs — the first suggests two entities, but no unity; whilst the second suggests something much stronger: that the mixture of the snake and the sinner has brought about a more extreme dissolution whereby not only does there cease to be a unity but the original entities cease to be, also. I think the second scenario is the more interesting one, since it it speaks to the opposite of a unity. We usually think of a unity — for example, as with the holy trinity — as a case where several wholes, coming together, both preserve their wholeness and also make some new entity which is something more than the sum of its parts. Dante’s “neither two nor one” suggests the opposite: a mingling where not only is there no unity, but wholeness of the ‘ingredients’ are themselves dissolved.

In either case, however, the question that arises is: what are Dante’s grounds for distinguishing when a combination is a unity and when it is not? That is, on what basis can he claim that the sinner/snake combination forms a (spatio-temporally continuous) ‘nothing’ rather than a novel (albeit horrific) ‘something’?

I do see how Dante is constrained, in describing the ‘nothing’ that is the snake and the sinner combination, by the need to apply his description to ‘something’ (!). But although it seems in general okay to say that a spatio-temporally continuous entity may nevertheless fail to be a genuinely novel entity — in the sense that the father, the son and the holy ghost make the holy trinity, or in the sense that a pair of lovers might make a love union — the interesting question (it seems to me) is under which circumstances we accept that a combination has produced something new and under which circumstances we claim that it has resulted in a dissolution. In other words, what would Dante say to someone who insisted that the snake/sinner combination forms a (devilish) unity just as much as a union of lovers does?

Perhaps there is no answer to this question. Someone might just hold that whether a new thing is created from a combination is simply a brute fact, about which nothing further can be said. But that would be disappointing, I think, especially for someone with interests in the metaphysical aspects of spirituality, as Dante has. Shouldn’t there be a reason why lovers merge to create something new and better whilst sinners merge to create nothing at all?

Return to top

Return to top