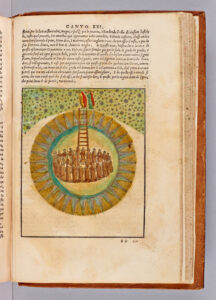

The contemplative souls sweep in a compact swirl upward in Paradiso 22.99 — “poi, come turbo, in sù tutto s’avvolse” (then, like a whirlwind, upward, all were swept) — and, in verse 100, Paradiso 22 shifts gears and begins to transition to the next heaven: the heaven of the fixed stars. This is the famous eighth heaven, “la spera ottava” of Paradiso 2.64: this is the first of the non-planetary heavens, which plays such an important role in the discussion of mandatory difference in Paradiso 2.

Before verse 100, the events of Paradiso 22 are still occurring in the seventh heaven, the heaven of Saturn, devoted to the contemplatives, “contemplanti”:

Questi altri fuochi tutti contemplanti uomini fuoro, accesi di quel caldo che fa nascere i fiori e ’ frutti santi. (Par. 22.46-48)

These other flames were all contemplatives, men who were kindled by that heat which brings to birth the blessed flowers and blessed fruits.

Dante designs the heaven of Saturn to focus on great saints and founders of religious orders. His contemplatives, in other words, are souls who were quite active while alive. He also covers a wide swath of monastic history in the heaven of Saturn, bookending the heaven between two saints whose deaths are separated by half a millennium. Paradiso 21 features an encounter with Saint Peter Damian, who died in 1072, while Paradiso 22 features an encounter with Saint Benedict, founder of the Benedictine order, who died in 543.

There is a history of monasticism traced in the pages of the Commedia, and in this heaven Dante sketches two distinctive and important moments in that history. As did Saint Peter Damian and Saint Thomas and Saint Bonaventure before him, Saint Benedict also speaks pungent words about the current degeneracy of the order that he founded.

Dante engages a wide gamut of saints and religious orders in the Paradiso, from the very early (in the next heaven he will encounter Christ’s own disciples) to the very recent.

The chilliness of Paradiso 21 has dissipated. Peter Damian’s emphatic insistence on lack of affect in his encounter with the pilgrim is reversed by Benedict. The affection of Saint Benedict is such as to open up the pilgrim’s confidence like a rose that is opened by the warmth of the sun:

E io a lui: «L’affetto che dimostri meco parlando, e la buona sembianza ch’io veggio e noto in tutti li ardor vostri, così m’ha dilatata mia fidanza, come ’l sol fa la rosa quando aperta tanto divien quant’ell’ha di possanza.» (Par. 22.52-57)

I answered: “The affection that you show in speech to me, and kindness that I see and note within the flaming of your lights, have given me so much more confidence, just like the sun that makes the rose expand and reach the fullest flowering it can.

The pilgrim’s confidence takes the form of a question that might seem even more presumptuous than the one he put to Peter Damian in the previous canto, but here he is not rebuked. Dante tells Benedict that he wants to see him with his face unveiled, “con imagine scoverta” (60): in other words, in his human body rather than as a living light. Benedict tells him, quite surprisingly, that this wish will be granted to him when he reaches the final sphere:

Frate, il tuo alto disio s’adempierà in su l’ultima spera, ove s’adempion tutti li altri e ’l mio. (Par. 22.61-63)

Brother, your high desire will be fulfilled within the final sphere, as all the other souls’ and my own longing will.

Benedict’s revelation that Dante’s wish to see him in his human form will be fulfilled at the end of his journey, in the Empyrean, is a remarkable concession that Dante-poet makes to Dante-pilgrim, since the souls will only get their bodies back at the Last Judgment. Benedict goes on to define and characterize the Empyrean in verses that stand as one of Dante’s great attempts to describe in language that which is beyond human, and hence linguistic, comprehension:

Ivi è perfetta, matura e intera ciascuna disianza; in quella sola è ogne parte là ove sempr’era, perché non è in loco e non s’impola; e nostra scala infino ad essa varca, onde così dal viso ti s’invola. (Par. 22.64-69)

There, each desire is perfect, ripe, intact; and only there, within that final sphere, is every part where it has always been. That sphere is not in space and has no poles; our ladder reaches up to it, and that is why it now is hidden from your sight.

As noted in the Commento on Paradiso 21, the heaven of Saturn offers many signposts to mark this “place” as the beginning of the end of the pilgrim’s journey. No signpost is more emphatic than the verses of Paradiso 22 cited above, where Benedict talks explicitly about the “ultima spera” (the final sphere [62]) as the no-place of complete fulfillment that is utterly beyond space-time.

The many markers of the beginning of the end in Paradiso 22 include:

- verses 34-35: “Ma perché tu, aspettando, non tarde / all’alto fine” (But lest, by waiting, you be slow to reach the high goal of your seeking);

- verses 61-62: “il tuo alto disio / s’adempierà in su l’ultima spera” (your high desire will be fulfilled within the final sphere);

- verses 64-68: the description of the Empyrean as the place that is “no-place” and where all desire is perfected, and as the place to which the ladder of the heaven of Saturn climbs;

- verse 124, “Tu se’ sì presso l’ultima salute” (You are so near the final blessedness): because he is so near the end of his journey, Beatrice instructs the pilgrim to look back.

Most important of all as a signpost that we are nearing the end of our journey is the requirement that the pilgrim look back at earth.

The pilgrim begins to transition to the heaven of the fixed stars in verses 100-02. He enters the eighth heaven in verses 110-11, and not just anywhere, but specifically at “the sign that follows Taurus”: “io vidi ’l segno / che segue il Tauro e fui dentro da esso” (I saw, and was within, the sign that follows Taurus). The “sign that follows Taurus” is Dante’s natal sign, Gemini. The poet prays to his natal stars for strength in a poignant and deeply personal passage where he refers to his birth as the moment when he first felt the Tuscan air: “quand’io senti’ di prima l’aere tosco” (when I first felt the air of Tuscany [117]).

Beatrice then instructs him, as preparation for the final leg of his journey, to look back at the distance that he has traversed. Beatrice establishes causality between reaching the end and the controlled Orphism that is now required of Dante. Like Orpheus, he must look back; unlike Orpheus, he does so in order to prepare his vision for the ultimate sight.

In The Undivine Comedy I contrasted Beatrice’s instruction in the heaven of the fixed stars to the angel’s instruction as Dante passes through the gate of purgatory:

The controlled Orphism of this experience is a potent indicator of how far we have come from Purgatorio 9, where the angel who guards the portal warned the travelers not to look back, because “di fuor torna chi ’n dietro si guata” (he who looks back returns outside [132]). If now Beatrice issues the contrary order, instructing the pilgrim to do what the angel warned against, it is because he has achieved such perspective that looking back is no longer perilous; by the same token, if the old perils exist no longer, the journey must be almost over. Looking back is no longer a nostalgic lapse, mandated by excessive desire; it is, instead, an action whose paradoxes exemplify the paradoxes of the Paradiso as a written form.

(The Undivine Comedy, p. 223)

There are two occasions in Paradiso when the pilgrim is instructed to look down, at the end of Paradiso 22 and the end of Paradiso 27. The first Orphic moment comes at the beginning of the heaven of the fixed stars and the second at the end of the heaven of the fixed stars. Thus, controlled Orphism frames the eighth heaven, further distinguishing a heaven whose importance as the First Differentiator of being — the very differentiated and multiform being at which the pilgrim is now formally instructed to look back — was discussed as early as Paradiso 2.

The passage at the end of Paradiso 22 details the pilgrim’s gaze down through the seven planetary heavens all the way to the earth, called, with immense sadness, “the little threshing floor that so incites our savagery”: “l’aiuola che ci fa tanto feroci” (151).

Return to top

Return to top