In Purgatorio 24, the encounter with Forese Donati continues. Dante asks his friend the whereabouts of his sister Piccarda. He learns that she is in Paradise, and indeed we will meet her in Paradiso 3. There are only two families whose members appear distributed throughout the three realms of the afterlife. The Donati family is one: Corso Donati is destined for Hell, as we learn in this canto; Forese Donati is in Purgatory, on the sixth terrace (Purgatorio 23-24); and Piccarda Donati is in Paradise, in the first heaven (see Paradiso 3).

The other family that figures in all three realms is that of the emperor Frederick II: the Emperor himself is among the heretics (see Inferno 10); his son Manfredi is among the excommunicates in Ante-Purgatory (see Purgatorio 3); while Manfredi’s mother, the Empress Constance, is with Piccarda Donati in the first heaven of Paradise (see Paradiso 3).

Purgatorio 21 and 22 were intensely focused on epic poetry, poetry with a social mission to record the history of a whole people and transmit their cultural values. Since Purgatorio 23 and the meeting with Forese, the focus has shifted to lyric love poetry: poetry centered on the interiority of one person, the lover/poet. Dante is heir to a vigorous lyric tradition that came to Sicily from Provence, moving up the Italian peninsula from Sicily to Tuscany. Dante now subjects this tradition to scrutiny. Those readers who would like to consult a synthetic overview of this tradition, see my essay “Dante and the Lyric Past”, in Coordinated Reading.

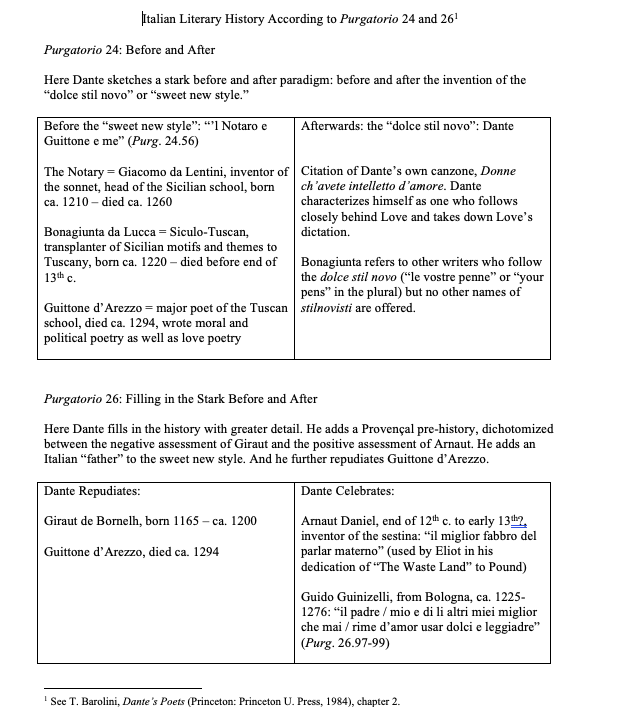

In Purgatorio 24 and Purgatorio 26 Dante writes a historiography of the lyric tradition: what he says about other poets in these canti became the outlines of a literary history that has lasted to this day. You can pick up any history of Italian literature and you will find a chapter devoted to the dolce stil novo, a school of poetry Dante invents and baptizes in Purgatorio 24, verse 57. Dante’s opinions on fellow poets, as expressed in the Vita Nuova, Convivio, De Vulgari Eloquentia, and especially in the Commedia, long ago attained canonic status. Here is a chart in which I distill the major components of this history as expressed in Purgatorio 24 and 26.

Forese introduces the wayfarers to a group of gluttons, including the poet Bonagiunta da Lucca (ca. 1220-1290), a character to whom Dante-poet has assigned the task of recognizing Dante-pilgrim as the originator of the “sweet new style” of lyric love poetry. In other words, Dante has chosen Bonagiunta as the character who will proclaim Dante the revolutionary change agent who will move Italian poetry in a new and infinitely more important and fulfilling direction.

Fascinatingly, Dante has chosen for this role in his afterlife a man who in real life was adverse to the direction in which Dante would take the Italian lyric. The real Bonagiunta belonged to the generation before Dante’s and was a conservative of the old school. He strongly critiqued the beginnings of change already visible in the poetry of Guido Guinizzelli of Bologna (ca. 1225-1276), also of the generation before Dante.

Bonagiunta da Lucca was a poet of the Tuscan school and a follower of Guittone d’Arezzo. He wrote the sonnet Voi ch’avete mutata la mainera (cited in full below), in which he accuses Guido Guinizzelli of Bologna of “changing the manner of pleasing love poetry”. How, in Bonagiunta’s accusation, had Guinizzelli made his deplorable changes to the genre of love poetry? He had, says Bonagiunta, inappropriately imported into the love lyric the philosophical wisdom of Bologna (“’l senno di Bologna” in the penultimate verse):

Voi ch’avete mutata la mainera de li piagenti ditti de l’amore de la forma dell’esser là dov’era, per avansare ogn’altro trovatore, avete fatto como la lumera, ch’a le scure partite dà sprendore, ma non quine ove luce l’alta spera, la quale avansa e passa di chiarore. Così passate voi di sottigliansa, e non si può trovar chi ben ispogna, cotant’è iscura vostra parlatura. Ed è tenuta grave ’nsomilliansa, ancor che ’l senno vegna da Bologna, traier canson per forsa di scritura.

You, who have modified the style of writing pleasant poems of love from how they used to be composed, to best all other lyricists, have acted like a beam of light that fills the darkness with its rays, but not here where the great star flares, which outshines all in brilliancy. Your subtleties are so pronounced that none can make out what you mean, because your speech is so obscure. And it is thought quite fanciful, despite Bologna’s learnedness, to quote theology in verse. (trans. Richard Lansing)

The point of the historical Bonagiunta is that love poetry was more pleasing before poets began to follow the new-fangled fashion of writing poetry that was tinged with philosophy and theology.

Of course, the philosophical and theological trend of the Italian lyric tradition is the trend that leads ultimately to Dante’s idea that the lyric love lady — Beatrice — can lead to God. In other words, it is the trend that leads to the Commedia. So, Dante here casts a poet of the old school, one who was explicitly against the new philosophical ways initiated by Guido Guinizzelli, as the celebrator of a new kind of poetry: the “nove rime” of Purgatorio 24.50.

Bonagiunta asks Dante-pilgrim if he is the author of the canzone Donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore, which he treats as the exemplar of “nove rime” or “new rhymes”. Here Bonagiunta explicitly gives the credit for the beginning of this new style to Dante’s youthful canzone:

Ma dì s’i’ veggio qui colui che fore trasse le nove rime, cominciando “Donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore”. (Purg. 24.49-51)

But tell me if the man whom I see here is he who brought the new rhymes forth, beginning: “Ladies who have intelligence of love.”

The canzone Donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore is the canzone that Dante placed in the Vita Nuova as marker of the breakthrough moment when he leaves behind the tired conventions of desiring a reward from the lady and instead locates his desire only in what he can do for her, and thus in “quelle parole che lodano la donna mia” (“those words that praise my lady”). Donne ch’avete, which you can read with my commentary and in Richard Lansing’s wonderful translation in Dante’s Lyric Poetry, was written when Dante was a young man. In the canzone the young poet already posits a fully theologized figure of the lady.

The wonder of Dante’s Beatrice is that she is both historical, a young woman whom he figures as real and beautiful and known to him, and at the same time she is exalted, mythologized. More precisely she is theologized. For, as Dante writes of Beatrice in Donne ch’avete, she is desired in highest heaven: “Madonna è disiata in sommo cielo” (Donne ch’avete, 29). He is already projecting Beatrice in the place that she temporarily leaves in order to descend to Limbo to summon Virgilio, as recounted in Inferno 2.

In other words, Donne ch’avete is a poem that moves the love lyric in precisely the direction that the historical Bonagiunta da Lucca rejected.

Dante now explains to Bonagiunta that he gets his inspiration directly from love:

E io a lui: “I’ mi son un che, quando Amor mi spira, noto, e a quel modo ch’e’ ditta dentro vo significando”. (Purg. 24.52-54)

I answered: “I am one who, when Love breathes in me, takes note; what he, within, dictates, I, in that way, without, would speak and shape.”

Dante’s self-characterization in the above famous verses is both material and metaphysical. It is material because he is a note-taker, a scribe, and indeed a transcriber: as Love dictates, so does he take note. It is important, moreover, that his action of taking note is immediate: the verb notare is in the present tense (“noto” I take note). Dante is a poet who takes notation as Love dictates — not belatedly, but immediately.

Dante’s self-characterization is metaphyscial because the force that dictates to him while he takes note is Love, and whether that be the Love of the lyric tradition or the transcendent Love that moves the universe with which the Commedia ends, it is not a material but a metaphysical principle.

As a response to the pilgrim’s mystical and metaphysical claim that he writes poetry by following the dictation of love, Bonagiunta replies with a ready-made historiography, somehow intuited from the pilgrim’s opaque remarks:

«O frate, issa vegg’io», diss’elli, «il nodo che ’l Notaro e Guittone e me ritenne di qua dal dolce stil novo ch’i’ odo! (Purg. 24.55-57)

“O brother, now I see,” he said, “the knot that kept the Notary, Guittone, and me short of the sweet new manner that I hear.

Naming three important leaders of previous Italian lyric schools — the “Notary” or Giacomo da Lentini, a Sicilian poet, and the Tuscan poets himself and Guittone d’Arezzo — Bonagiunta declares that all three fell short of the “sweet new style” that he has just heard characterized by Dante. In this way, Dante-narrator follows up the inital declaration of the birth of “nove rime” (the rime that begin with his canzone Donne ch’avete) with a second declaration: Dante is responsible for the dolce stil novo, the sweet new style that takes its dictation directly from Love, dispensing with humdrum earthly intermediaries.

Dante’s historiographic categories in Purgatorio 24 and 26 became Italian literary history; to this day anthologies of Italian literature use Dante’s label dolce stil novo and arrange poets on either side of the great divide — the “nodo” — stipulated by Dante in this passage.

Structurally, the encounter with the Tuscan poet Bonagiunta da Lucca is embedded within the overarching encounter with Dante’s friend (and fellow Florentine) Forese Donati. Therefore, after the encounter with Bonagiunta the narrative returns to Forese, who prophesies the destruction of his own brother Corso Donati. The Donati family is one of the magnate families whose power struggles kept Florence in a constant state of conflict; Corso was a power broker and man of violence. The encounter between Dante and his old friend Forese ends however on an elegiac note, reminiscent of the preceding canto, as Forese reminds Dante that time is precious in purgatory: “che ’l tempo è caro / in questo regno” (for time is dear in this realm [Purg. 24.91-92]). Forese then takes his leave.

In conclusion the travelers come to another inverted tree, like the one we saw toward the end of Purgatorio 22, and this time it is specified that these trees on the terrace of gluttony are grafts from the tree of which Eve ate. In the following terzina the themes of prohibition and transgression — the themes that Dante introduces into his poem as UIyssean — are clearly aligned with the biblical injunction to Adam and Eve not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil:

Trapassate oltre sanza farvi presso: legno è più sù che fu morso da Eva, e questa pianta si levò da esso. (Purg. 24.115-17)

Continue on, but don’t draw close to it; there is a tree above from which Eve ate, and from that tree above, this plant was raised.

Given that the focus is on a “tree above from which Eve ate”, gluttony cannot be simply overeating in a literal sense. The canto ends with the concept of measured and correct hunger: the Beatitude’s refrain “esuriendo sempre quanto è giusto” (“hungering always in just measure” [Purg. 24.154]) hearkens back to the “sacra fame dell’oro” (“sacred hunger for gold”) of Purgatorio 22.40-41.

Dante has found in the trees that he places on the terrace of gluttony a new way to yoke excessive desire for knowledge with the excessive desire purged in the top three terraces. In other words he has found in the trees grafted from the Garden of Eden a new way of figuring the nodo that preoccupies him in these canti: epistemological incontinence.

Return to top

Return to top