Paradiso 23 is a mystical canto. It does not engage in “plot” even in the minimal sense of plot in the Paradiso: there is no encounter with a soul or a dubbio that generates a lengthy discourse on a monastic order or on the papal curia, on good governance or social justice, on Florence or new wealth, on heredity, on the order of the universe, on human obligation and will, or on any of the manifold other topics that Dante has put before us.

There is, rather, an attempt to communicate the substance of the divine, as perceived and experienced in an “immediate” — in its etymological sense of un-mediated — encounter with the divine. This encounter is such that it provokes in Dante an ecstasis menti, literally an ec-stasis, a “standing outside of the mind”: an ecstasy, a raptus, in which “la mente mia . . . fatta più grande, di se stessa uscìo” (my mind, having grown more expansive, went outside of itself [Par. 23.43-44]).

In this canto the pilgrim experiences visions: a vision of the Advent of Christ, a vision of Christ Himself, who appears as a sun and as a man, a vision of the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation. These visions are all interwoven with sublime similes, invocations and prayers to the Transcendent Principle, and claims of poetic insufficiency.

To the degree that there is plot in Paradiso 23, it is provided by these visions, which the pilgrim experiences in this order:

- a vision 0f the Advent of Christ,

- a vision of the Ascension of Christ,

- a vision of the Annunciation to the Virgin,

- a vision of the Assumption of the Virgin.

These visions are thua dechronologized, given that in history the Annunciation of Mary’s pregnancy precedes the Advent of Christ’s birth.

Christ appears in His triumph, surrounded by all the souls whom He has redeemed:

e Beatrice disse: «Ecco le schiere del triunfo di Cristo e tutto ’l frutto ricolto del girar di queste spere!» (Par. 23.19-21)

And Beatrice said: “There you see the troops of the triumphant Christ—and all the fruits ingathered from the turning of these spheres!”

The pilgrim sees a sun that lights one thousand lamps (“un sol che tutte quante l’accendea” [29]), and within that living light he sees an explosive presence: a “glowing substance” — “la lucente sustanza” (32) — so bright that that his gaze cannot sustain it. This explosive presence is Christ:

vid’i’ sopra migliaia di lucerne un sol che tutte quante l’accendea, come fa ’l nostro le viste superne; e per la viva luce trasparea la lucente sustanza tanto chiara nel viso mio, che non la sostenea. (Par. 23.28-33)

I saw a sun above a thousand lamps; it kindled all of them as does our sun kindle the sights above us here on earth; and through its living light the glowing Substance appeared to me with such intensity— my vision lacked the power to sustain it.

The “glowing substance” that Dante sees is Christ in His very self: His substance is His essence is His ontological being and presence in His resurrected body.

This stunning visionary moment of Paradiso 23 is broached again, in a more explanatory fashion, at the end of Paradiso 25, where Saint John explains that the only two souls who went to heaven with their bodies are Christ and Mary. Saint John refers to them, intratextually, as the two lights whom Dante previously saw rise up, thus glossing the vision of Paradiso 23:

Con le due stole nel beato chiostro son le due luci sole che saliro e questo apporterai nel mondo vostro. (Par. 25.127-29)

Only those two lights that ascended wear their double garment in this blessed cloister. And carry this report back to your world.

Because he is looking at the Christ, the pilgrim does not have the power to sustain his gaze. Like the pilgrim’s vision, the poem jumps away, into a non sequitur, in this case into an exclamation: “Oh Beatrice, dolce guida e cara!” (O Beatrice, sweet guide and dear! [34]). The exclamation “Oh Beatrice, dolce guida e cara!” is one of the textual components that Dante uses to fracture the narrative line in Paradiso 23, along with apostrophes, metaphoric language and affective similes.

I write in The Undivine Comedy of the “anti-narrative textual components” that Dante uses in Paradiso 23, in order to prevent a narrative line from forming:

The anti-narrative textual components of Paradiso 23 — apostrophes, exclamations, metaphoric language, and affective similes — are used by the poet to fracture his text; moments of plot are interrupted by an apostrophe, exclamation, or lyrical simile, deployed as a means of preventing a narrative line from forming. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 225)

The above analysis of Paradiso 23 is part of a larger analysis of the narrative texture of the Commedia, which takes its cue from the two versions of Dante’s dream in Purgatorio 9, which are analyzed at the end of chapter 7: one version is straightforward and realistic, the other is mystical and ecstatic. These two accounts are emblematic of the two basic narrative textures of the Commedia, which are allocated throughout the text in different ways:

Looking at the Commedia as a whole, we could say that the Inferno is composed mainly in the straightforward “realistic” manner, with the significant exception of the first part of canto 1; it is important to remember that Dante chooses to begin his narrative journey with a harbinger of alternatives to his dominant mode. The Purgatorio introduces longer “nonrealistic” passages, concentrated in the sections devoted to the dreams, the reliefs, the visions, and so forth; while in the Paradiso the ecstatic visionary mode comes into its own, and the proportion of text devoted to it increases. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 164)

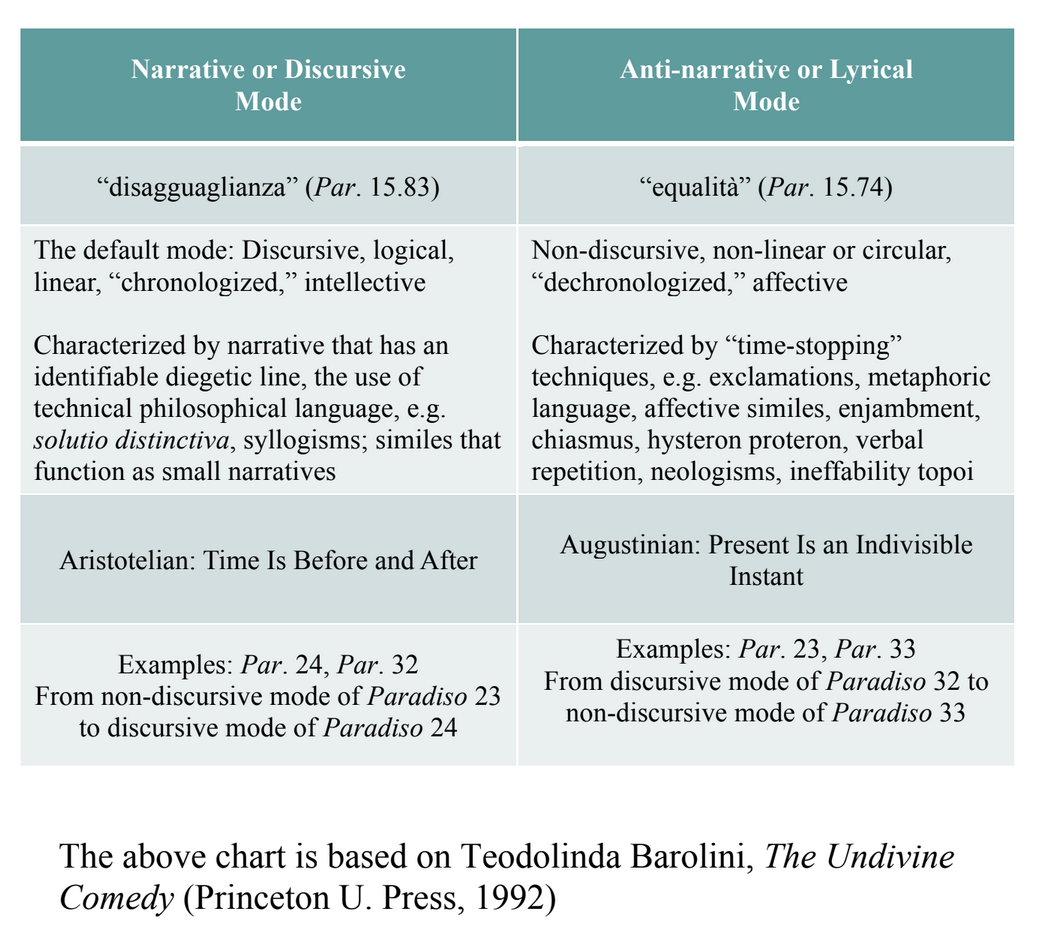

Here is a chart of the Paradiso’s two basic narrative modes, as analyzed in The Undivine Comedy, and as applied to Paradiso:

Along with apostrophes, exclamations, metaphor, and lyrical similes, the other key anti-narrative component is the ineffability topos. To this last category belongs one of the poem’s great metapoetic moments, which falls in the center of Paradiso 23. Dante says that his poem can no longer hold to its course, that it has to swerve, leap, jump, as “one whose path is cut off”:

e così, figurando il paradiso, convien saltar lo sacrato poema, come chi trova suo cammin riciso. (Par. 23.61-63)

And thus, in representing Paradise, the sacred poem has to leap across, as does a man who finds his path cut off.

In other words, the linear narrative cammino of the poem, the narrative line that has been strung together in imitation of the pilgrim’s journey in which he encounters “le vite spiritali ad una ad una” (“the spiritual lives one by one” [Par. 33.24]), is now fractured. The narrative line is no longer sustainable, and so the sacred poem must jump.

In The Undivine Comedy I argue that this jumping discourse — this swerving into deliberate non sequitur — is programmatic, and that it constitutes Dante’s brilliant rhetorical response to the challenge of creating language that is non-differential and non-sequential. Language is always perforce differential and sequential; it must be so, since language exists in time. How then to approximate an impossibility: unified language, equalized language?

With various rhetorical techniques that serve to break the narrative line, and thus to approximate — as best one can in a temporal medium — a circularized discourse. As we are about to see, enjambment will be keep.

The great metapoetic affirmation of poetic inadequacy cleaves Paradiso 23 in two: the vision of the Advent precedes it and the vision of the Annunciation follows it.

Toward the end of the canto Dante transcribes the very song sung by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, calling it a “circulata melodia” (Par. 23.109). In effect, Dante is giving us his own characterization of the “voce modesta / forse qual fu da l’angelo a Maria” (modest voice, perhaps much like the angel’s voice in speech to Mary) of Paradiso 14.35-36.

Gabriel’s song is a supreme example of Dantean apparent simplicity. We notice that four of the six verses that comprise Gabriel’s song (verses 103 to 108) are enjambed: the unenjambed verses are the the verse that ends the angel’s first tercet (verse 105) and the verse that ends the song (verse 108). In other words, verses 103, 104, 106, and 107 are enjambed (I have indicated the final word of an enjambed verse in red):

«Io sono amore angelico, che giro l’alta letizia che spira del ventre che fu albergo del nostro disiro; e girerommi, donna del ciel, mentre che seguirai tuo figlio, e farai dia più la spera suprema perché lì entre». Così la circulata melodia si sigillava, e tutti li altri lumi facean sonare il nome di Maria. (Par. 23.103-11)

“I am angelic love who wheel around that high gladness inspired by the womb that was the dwelling place of our Desire; so shall I circle, Lady of Heaven, until you, following your Son, have made that sphere supreme, still more divine by entering it.” So did the circulating melody, sealing itself, conclude; and all the other lights then resounded with the name of Mary.

Dante here uses enjambment to create the kind of circularized discourse — divine, non-discursive, non-temporalized discourse — that he imagines to be proper to beings who do not use language. Angels of course have no need for language because they know everything in the mind of God and have no need for the form of communication language engages. Dante thus uses enjambment to create what he labels a “circulata melodia” (109), a “circulararized melody”, enjambing the verse that ends with “circulata melodia”: “Così la circulata melodia / si sigillava” (Par. 23.109-10).

In scripting for Gabriel a “circulata melodia”, Dante also gives us an indicator of the kind of divine discursiveness at which he himself aims. In other words, the “circulata melodia” that Dante here creates for Gabriel is an apt descriptor for Paradiso 23 itself. It is also an apt descriptor for the special kind of language that becomes more evident as we come closer to the end of Paradiso.

Enjambment is a rhetorical trope that provides an excellent entry-point for understanding Dante’s linguistic and poetic goals at this point in the poem, for enjambment runs over the unit of verse and thereby unifies it to its successor, while at the same time somewhat compromising the syntax by not acknowledging and closing off the syntactic unit if it falls at the end of the line. As the word “enjambment” itself signifies, a “leg” (French “jambe”) is thrown over from one verse to the next, disabling the clear units of syntax but unifying the verses.

Thus the result of enjambing is effectively to “circularize” or de-narrativize the verse. In this way, enjambment is an analogue to other rhetorical moves that Dante employs in the Paradiso to circularize and de-narrativize his verse, such as hysteron proteron and chiasmus.

The narrative texture of Paradiso 23 can be understood as an example of enjambment writ large. The constant fracturing of the narrative cammino — the constant forcing of the poem to “jump, as one who finds his path cut off” (62-63), the jumping from plot to invocation to apostrophe to simile to some more plot followed by another simile and another apostrophe — results in poetry that has been circularized and de-narrativized.

In fact, Paradiso 23 is in effect a large-scale circulata melodia. Or, to reverse: circulata melodia is the small-scale emblem of the linguistic experiment that is Paradiso 23. For the entire canto is, as I note in The Undivine Comedy, “a kind of macro-enjambment”:

The circulata melodia that describes both the angel’s circling movement and his song is an apt if untranslatable label for the entire canto, itself a “circulated melody.” For the result of fracturing the discourse, of jumping about rhetorically — from plot to invocation to apostrophe to a simile to some more plot followed by another simile and another apostrophe — is, paradoxically enough (in an effect similar to that produced, on a local scale, by enjambment), to create a peculiarly unified or equalized linguistic texture: a texture from which disagguaglianza has been to some degree banished, a circulata melodia. The jumping discourse that governs canto 23 could be seen as a kind of macro-enjambment: enjambment operating not between individual verses but between segments of a canto. The jumping discourse is obtained by way of a poetics of enjambment, by way of a rupture that unifies. Canto 23 is in fact a strangely cohesive text, one that could be plucked entire out of the narrative fabric of the Commedia. Its unity is conferred by its lack of easy divisibility, its defiance of linear narrativity, in a word, by the fact that it jumps. (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 228-29)

What I offer in the next paragraph is my rendering of the broken narrative line of Paradiso 23, the fractured line that results in a de-narrativized and highly lyricized textuality. Every arrow indicates a jump.

Canto 23 begins with lyrical affective Simile number 1, of a mother bird feeding her young (1-15), followed by → A moment of plot: the Advent of Christ in triumph (19-21), which leads to → An expression of poetic inadequacy (22-24) → Another simile: intensely lyrical and destabilized/destabiliizing Simile number 2, in which Trivia (Diana/moon) surrounded by stars is compared to the Sun/Christ lighting up thousands of luminous souls who follow in Christ’s triumph (25-30) → A moment of plot: Dante-pilgrim sees Christ as “lucente sostanza”, in his essence/form/flesh, such that his sight cannot sustain it (31-33) → Nor can discursive language be sustained! → Immediately the text jumps, in the next verse, to an exclamation: “Oh Beatrice dolce guida e cara!” (34) → A moment of plot: Beatrice explains what Dante has just seen (35-39) → Simile number 3, which is also plot, since it tells of the pilgrim’s visionary experience of excessus mentis (the mind exiting from itself): as a lightning bolt is created by expanding until it is unleashed from the cloud and then falls down, so his mind expanded until it exited from itself, in a literal excessus mentis (40-44) → The mystical experience leads to a statement of representational inadequacy, as the narrator tells us that he cannot remember what happened: “e che si fesse rimembrar non sape” (45) → A moment of plot: Beatrice tells Dante to open his eyes, for he has seen things that enable him to tolerate her smile (46-48) → He hears Beatrice’s offer (49-54), and is like one who tries in vain to recall a “visione oblita” (50; see Par. 33 for similar expressions) → The great metapoetic passage that splits the canto (55-69), fully interrupting a text already subjected to continuous interruption, and that simultaneously, while disrupting, theorizes the disruption of the narrative line, with the verse “convien saltar lo sacrato poema” (62) → A moment of plot: Beatrice instructs him to look at the garden flowering under Christ’s rays, where he will see — this is metaphor, not simile — the rose in which the word was made flesh (70-75) → The pilgrim tries again, giving himself again to the “battaglia de’ debili cigli” (76-78) → Simile number 4 (79-84): As a ray of light illuminates a “prato di fiori”, so he sees “turbe di splendori, / folgorate di sù da raggi ardenti, / senza veder principio di folgori” (82-84); in other words, he sees the blessed souls lit from above with burning rays, without seeing the origin of those rays, because the Christ Who led them in triumph has ascended to the Empyrean → Prayer to Christ (86-88), in which Dante thanks Him for ascending so that he (Dante) is able to see the other souls: “su t’essaltasti, per largirmi loco . . .” (86) → He turns his soul entirely to the largest remaining flame, Mary (88-93) → A section of plot in verses 94-111, a section that constitutes the most sustained plot point of the canto: 1) a torch arrives in the form of a circle and begins to sing (94-102); this is the arrival of the angel Gabriel; 2) Gabriel’s performance of the Annunciation, culminating in Gabriel’s song (103-111), a “circulata melodia” (109) that is a rhetorical mise-en-abyme of Paradiso 23 → Dante-pilgrim sees the Primo Mobile far off in the distance (112) → Simile number 5, another simile of intense affect, which circles back to mothers and infants as at the canto’s beginning: now, rather than the mother bird’s desire to feed her young, we have the nursing child’s intense desire for the mother’s milk (121-26) → The conclusion of the canto moves toward discursivity with the introduction of Saint Peter.

The last verse of this canto is a periphrasis referring to Saint Peter, “colui che tien le chiavi di tal gloria” (he who is keeper of the keys of glory [Par. 23.139]), and is already an introduction to the very different tone — the return to linear narrativity and discursivity — that will dominate the “examination cantos” that follow.

Return to top

Return to top