Purgatorio 19 offers us an opportunity to remember the thematic importance of Ulysses in Dante’s Commedia. This importance is reflected in The Undivine Comedy, where Ulysses is a thematic thread who winds through the whole book. Ulysses is unique (with his avatar Nembrot) in being a sinner who is named in each of the three cantiche of the Commedia. Ulysses’ named moment in Purgatorio occurs in Purgatorio 19: the Greek voyager is featured in the pilgrim’s dream that is recounted at the outset of the canto. If you would like to refresh yourself on the Ulyssean thematic, see The Undivine Comedy, Chapter 3, “Geryon, Ulysses, and the Aeronautics of Narrative Transition.” Particularly relevant for the dream of Purgatorio 19 and for the canti of excess desire in Purgatorio (the top three terraces) is Chapter 5 of The Undivine Comedy, “Purgatory as Paradigm,” especially from p. 105 to the end of the chapter.

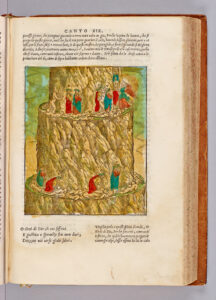

Purgatorio 19 begins with a dream. It is nighttime, the second night that Dante-pilgrim spends on Mount Purgatory.

The first time that Dante falls asleep, in Purgatorio 9, the pilgrim is in a transitional moment, transitioning from Ante-Purgatory to the gate of Purgatory proper. In Purgatorio 9 the pilgrim dreams that he is seized and swept to heaven by a terrifying eagle, as when Ganymede was seized by Jove in the form of an eagle and as St. Paul was “rapt” to the third heaven (2 Corinthians). After his dream, Dante learns from Virgilio that while he was dreaming of raptus, Santa Lucia (Saint Lucy) safely carried him from the Valley of the Princes up to the gate of Purgatory.

Now, in Purgatorio 19, the pilgrim dreams again, and again he has arrived at a transition: the transition from lower Purgatory to upper Purgatory. The third and final dream of Purgatorio will occur in canto 27, where Dante transitions from Purgatory to the garden of Eden, the Earthly Paradise that sits atop Dante’s mountain.

As compared to the first dream, whose language is rich and evocative but whose action is fairly simple (Dante is carried aloft, in a terrifying manner), the dream of Purgatorio 19 recounts a complex drama. First, Dante is seduced by a woman, one who calls herself the very siren who seduced Ulysses. Then, the siren is unmasked by another woman, who rebukes Virgilio for not being more attentive. Thus the drama involves a “bad” woman and a “good” woman, along with three male protagonists: Dante, Ulysses in absentia, and Virgilio. The complexity of the dream can be seen from the following list of five dramatis personae.

Dream of Purgatorio 19: Five Dramatis Personae

- the “femmina balba” (“stuttering female”) of verse 7, a stuttering and deformed figure who is transformed by the dreamer’s gaze into a hyper-articulate, non-stuttering and very charismatic “dolce serena” (sweet siren [19]), who promises complete satisfaction of desire: “sì tutto l’appago!” (so completely do I satisfy him! [Purg. 19.24]). She presents herself as the very siren who sang to Ulysses and turned him from his path: “Io volsi Ulisse del suo cammin vago / al canto mio” (I turned Ulysses from his path with my song [Purg. 19.22-23]);

- the pilgrim himself, whose longing and transformative gaze threatens to get him into trouble (note the connection to the way that love takes root in the soul, through the gaze, as described in Purgatorio 18);

- Ulysses, not present “in person” but featured in the siren’s song; she says that she is the one who sang to Ulysses and turned him from his path, thus literally “se-ducing” him (< Latin sēdūcere, to lead aside, equivalent to sē-+ dūcere, to lead); she thus makes a direct analogy between Ulysses — to whom she sang in the past — and Dante, to whom she sings now;

- the “good” woman who reveals the deceptive nature of the siren, showing her to be not beautiful but rotten and stinking; this is a “donna santa e presta” (a lady alert and saintly [ 19.26]): not a “femmina” (disparaging in Italian) but a “donna” (“lady”, an honorific);

- Virgilio, overtly chastised by the “donna” for having allowed the siren to make such inroads into Dante’s consciousness; he is responsible for “guarding the threshold of assent” (in the metaphor of Purgatorio 18), and is therefore emblematic of reason and free will. In the sonnet Per quella via che la Bellezza corre, reason plays a similar role in defending the self from the incursion of wrong desire.

In the dream the donna santa arrives and dramatically undresses the siren, exposing her stomach and her stench. Never before have we seen misogynistic and physically disparaging language in Dante’s treatment of women. This is because the siren is not a female character with an ontological and historical existence. She is not an esser verace, to use the language of Purgatorio 18.22. She is an entirely abstract and symbolic figure.

Nonetheless, the symbolism is based in a representation of women, and in that respect it is inherently misogynist. Having gone out of my way to insist on Dante’s progressive treatment of women, it is incumbent on me to signal his less progressive moments as well.

Dante has a long history of creating polarities between female figures (for example, the donna gentile of his stilnovist lyrics versus the donna pietra of the rime petrose), he did not, in earlier variants of this scenario, write in such misogynistic and disparaging language of the woman doomed to be defeated. In fact, in his earlier polarities, there is a woman who was loved first and a woman who was loved second, both are “donne” (neither is a “femmina”), and the ethical struggle that ensues involves the legitimacy of transitioning from one love to another. This is the pattern that we observe in the sonnet Per quella via che la Bellezza corre and also the opposition that Dante creates between Beatrice and the donna gentile, first in the Vita Nuova and then in the Convivio. This is the pattern that I believe is dominant in his writing, and that will come to a climax in Beatrice’s rebuke in Purgatorio 30.

The femmina balba of Purgatorio 19, who will shortly be called by Virgilio an “antica strega” (ancient witch [Purg. 19.58]), is in fact an entirely symbolic construct. She is not a historicized object of desire: not an actual woman of flesh and blood whom Dante loved — we remember that Dante was notorious as a lover and slated for the terrace of lussuria by Leonardo Bruni — and later critiqued himself for loving. She does not engage the complex historical forms of signifying, sutured into Dante’s own life and will, that are engaged by Lisetta of Per quella via and by the donna gentile.

The siren is, as Virgilio will in fact tell us, an allegorical figure, of symbolic value. She symbolizes those seductive secondary goods — called by St. Thomas “changeable goods” — that lead the soul astray, and that are characterized as false and misleading at the end of Purgatorio 17:

Altro ben è che non fa l’uom felice; non è felicità, non è la buona essenza, d’ogne ben frutto e radice. (Purg. 17.133-35)

There is a different good, which does not make men glad; it is not happiness, is not true essence, fruit and root of every good.

These false goods, like the femmina balba/dolce serena/antica strega, claim to be able to completely satisfy us but can never do so. In the above terzina, the poet’s emphasis is on what these goods cannot do: they cannot make us happy, much as they promise to do so, because only the Primary Good — that which, in Augustine’s and Aquinas’s language, will never change — can truly satisfy our desires.

Virgilio proceeds to explain the dream of the siren as in Purgatorio 9 he previously explained the dream of the eagle. He explains that Dante saw “quell’antica strega / che sola sovra noi omai si piagne”: “that ancient witch who alone causes the weeping above us” (Purg. 19.58-59). Virgilio here explicitly aligns the dolce serena with the vices that are purged “sovra noi” — “above us” — which is to say, with the vices of the top three terraces. He explicitly equates the siren — first beautiful and alluring, then revealed as grotesque and revolting — with the false allurements of avarice, gluttony, and lust.

Dante, in having Virgilio gloss the dream of the siren in this way, thus also lets us know that the top three terraces of Purgatory are of special interest to him. To start with, he unifies them, explicitly classifying them as a unit in verse 59. Moreover, he has prepared us for for this unity by placing a dream-transition at the beginning of Purgatorio 19. But why should there be a transition here, specifically? We traditionally gloss the transition as the passage to Upper Purgatory, but that is a somewhat thoughtless gloss. Where are we precisely?

To answer that question we need to go back to the taxonomy of the seven vices offered by Virgilio in the pause of Purgatorio 17. That taxonomy divides the seven vices into two categories: the first category, consisting of the first three terraces, comprises the vices that involve love for the wrong object (pride, envy, anger); the second category, consisting of the top four terraces, comprises the vices that involve love for the right object but that is expressed in the wrong way, with too little vigor (sloth), or with too much vigor (avarice, gluttony, lust).

If the seven terraces needed to be divided between “lower” and “upper”, the obvious place to mark a separation is between the two large categories created by Virgilio’s taxonomy, and thus between the first three terraces and the subsequent four terraces.

Instead, Dante puts his transition before the top three categories, in effect cordoning off the sins of incontinence: avarice, gluttony, and lust. Doing so, he shows us his passionate interest in incontinence, in excess, in “troppo di vigore”. His interest is such that he effectively creates a composite super-vice out of the top three terraces, that which ”alone causes weeping above us” (59). Indeed, as we shall see, he takes steps at a linguistic level as well to blend the vices of the top three terraces.

Another way to say this is to use the language of Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas defines two elements of sin: “aversion, the turning away from the changeless good” (aversio ab incommutabili bono) and “conversion, the disordered turning toward a changeable good” (inordinata conversio ad commutabile bonum). See ST 1a2ae.87.4; Blackfriars 1974, 27:24–25; cited in “Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell,” p. 112.

The symbolic female figure of the dream of Purgatorio 19 is the embodiment of St. Thomas’s negative conversio, of “disordered turning toward a changeable good”: hence the siren says “volsi,” “I turned him,” in Purgatorio 19.22. If false and changeable goods could come to life and literally beckon to us and turn us from the right path, they would speak with the voice of the dolce serena. And they would smell, when we have had our full and have realized our error, with the stench of the unclothed femmina balba.

Yet another way to say this is to use the language of the parable of Convivio 4.12, where the pilgrim-soul goes along the road of life looking for the albergo and is constantly deceived, thinking it has found a place of rest (an unchangeable good) when in fact it has found only more changeable goods, in which it can never rest.

In Purgatorio 19, Dante has greatly complicated his dramatization of seduction by false goods by 1) suggesting a connection with the way the lover of the courtly tradition gazes at and configures his beloved; 2) rendering the embodiment of false goods in such misogynistic language and creating a seductive drama of “bad female” versus “saintly lady”; 3) transposing the parable of the traveling soul from land to sea, and recasting it in the terms of his personal mythography, through the invocation of Ulysses.

Indeed, Dante goes out of his way to place at the threshold of the sins of incontinence the figures of Ulysses and the siren, thus reminding us of Cicero’s praise for the hero who was so consumed by the “discendi cupiditas” — the desire to learn — that he caused himself to be bound to the mast so that he could hear the sirens sing.

In other words, we as critical readers need to ask: Why does the siren who signifies attraction to fraudulent secondary goods say that she sang to Ulysses? This is the question that I pose on p. 105 of Undivine Comedy. The answer is that Dante seeks to expand our understanding of what is at stake for him in the concept of excess desire. By naming “Ulisse” he seeks to transition us from considering excess desire only in the context of material goods to considering the “Ulyssean” — i.e. Dantean — issue of excess desire for knowledge.

The invocation of Ulysses by the siren is a way of bringing a more expansive form of incontinence into focus. Dante is indicating that the top three terraces of purgatory deal with more than excess desire for material goods. They deal, as I show in The Undivine Comedy, with epistemological or intellectual incontinence.

In the second half of Purgatorio 19, Dante and Virgilio come to the fifth terrace, the terrace that we presume to be (following the order of the seven capital vices) the terrace of avarice. Dante speaks to a soul who is purging his avarice and who was a pope: Pope Adrian V. Elected pope in 1276, Adrian V died after only 38 days.

The Commedia certainly associates the clergy with avarice, and Dante does not shy away from associating even popes with a sin that he thought corrupted the Church, as we saw in Inferno 7 and again in Inferno 19. However, in the encounter with Pope Adrian, Dante treats avarice in a more metaphorical than literal way, as lust for power, more than lust for gold. Adrian V talks not about money but about his temporal ambition, and gives a remarkable account of how temporal ambition can take a man all the way to the papacy:

La mia conversione, omè!, fu tarda; ma, come fatto fui roman pastore, così scopersi la vita bugiarda. Vidi che lì non s’acquetava il core, né più salir potiesi in quella vita; per che di questa in me s’accese amore. (Purg. 19.106-11)

Alas, how tardy my conversion was! But when I had been named the Roman shepherd, then I discovered the deceit of life. I saw that there the heart was not at rest, nor could I, in that life, ascend more high; so that, in me, love for this life was kindled.

Adrian V explains that his desire for power and position — the particular dolce serena that he is pursuing — is slaked only when he reaches the very highest point of the pinnacle that he is climbing. The voyage metaphor has mutated from a sea-voyage to a steep climb, but the principle is the same and poses the same question: are you traveling on the right path? Are you traveling on the path toward the right?

Only when Adrian V has reached the very highest temporal goal that a man in holy orders could possibly covet, only when he has become pope (“Roman shepherd” [107]), does he have the realization that will lead him to salvation. He has reached the very highest peak — there is nowhere remaining for his ambition to climb, just as there was nowhere remaining in the inhabited earth that Ulysses could still sail — and yet he is still not at peace, he is still not happy. In this way Adrian discovers that he is pursuing changeable goods that are deceitful and that will never give him peace. And, in that moment of discovery, he “converts”: his “conversion” is, as he says, late.

He converts, that is, away from secondary goods, even the highest, and toward the Primary Good. In Aquinas’ language, he turns away from what he had been turning toward: he turns away from that “disordered turning toward changeable goods” that had been driving him (“inordinata conversio ad commutabile bonum”). He converts away from secondary goods and converts toward the Primary Good.

The idea of a Pope who “converts” to God is really quite remarkable.

In this extraordinary passage, Dante indicts those who seek holy office as mere careerists like the rest of us. And what would have happened to Adrian V had he never reached the top? Would he never have understood his error? In this canto it becomes clear that for Dante, “avarice” ultimately goes beyond excess desire for gold to become excess desire of position and power. We have to take seriously the way that Adrian’s account transposes “avarice” from the literal to the metaphoric domains.

In Adrian’s surprising story we can see how Dante picks up on the metaphorizing of excess desire that is already implied by the name “Ulisse” in the dream, a name that moves excess desire toward intellectual incontinence, and we also see how he continues to push for a more metaphorical than literal treatment of the top three terraces.

Return to top

Return to top