In the concluding section of Paradiso 4, Beatrice’s “resolution” of the pilgrim’s dubbio gives way to a divinely eroticized paean to his beloved. On this note of saintly eros, Paradiso 4 ends and Paradiso 5 begins.

Intertwined with the hot language used in this passage for Beatrice (for example, the “faville d’amor così divine” in Beatrice’s eyes in Par. 4.140) is the much cooler — indeed economic — language of a new dubbio, introduced at the end of Paradiso 4. Dante, still meditating on Piccarda’s life story as recounted to him in Paradiso 3, wants to know whether it is possible to “satisfy” (as in “to satisfy a debt” or “to satisfy a creditor”) a broken vow with some other good than the one originally promised:

Io vo’ saper se l’uom può sodisfarvi ai voti manchi sì con altri beni, ch’a la vostra statera non sien parvi. (Par. 4.136-38)

I want to know if, in your eyes, one can amend for unkept vows with other acts— good works your balance will not find too scant.

Beatrice restates the pilgrim’s question in Paradiso 5, again emphasizing the economic, contractual, and even litigious/legal aspects of failing to maintain a vow:

Tu vuo’ saper se con altro servigio, per manco voto, si può render tanto che l’anima sicuri di letigio. (Par. 5.13-15)

You wish to know if, through a righteous act, one can repair a promise unfulfilled, so that the soul and God are reconciled.

Beatrice then launches into her replay with explanation. Before looking at what she says, I will give you some context. The Old Testament deals with the “economics” of the vows made by humans to God in Leviticus 27. The following breakdown of Leviticus 27 and definition of vows within the Old Testament are taken from a Bible-study website (it is but a portion of a much fuller analysis):

Source: http://bible.org/seriespage/value-vow-leviticus-27 (as accessed in 2014)

The Structure of Leviticus 27

The key to the structure of chapter 27 is to be found by the categories of things which are vowed as offerings to God:

- Vows of people—vv. 1-8

- Vows of animals—vv. 9-13

- Vowed houses—vv. 14-15

- Vowed inheritance (family land) vv. 16-21

- Vowed (non-family) land—vv. 22-25

- Illicit vows—vv. 26-33

- Conclusion—v. 34

The Definition of a Vow

Simply viewed, offering a vow is practicing a kind of “credit card” act of worship. It is a promise to worship God with a certain offering in the future, motivated by gratitude for God’s grace in the life of the offerer. The reason for the delay in making the offering was that the offerer was not able, at that moment, to make the offering. The vow was made, promising to offer something to God if God would intervene on behalf of the individual, making the offering possible. In many instances, the vow was made in a time of great danger or need. The Rabbis believed that the gifts which were vowed in Leviticus 27 were to be used for the maintenance of the Temple.

The Unique Contribution of Leviticus 27

While the teaching of Leviticus is consistent with that of the Old Testament as a whole, it makes some unique contributions. There are three principal lessons to be learned from the legislation of Leviticus 27, which set this chapter apart in its emphasis and methods. Let us consider each of these.

Leviticus 27 teaches men to be cautious about the vows they make, but in a different way than elsewhere. There are three principal ways in which the people of God are cautioned about making vows hastily, and without due consideration. First, there is the method of teaching. In the Law there are clear statements of warning and instruction about hasty vows, as we see above. Second, one can use examples and illustrations to teach. The Old Testament gives us several examples of men who made foolish vows, the most notable example being Jephthah, who vowed so generally that his daughter became the offering to the Lord (Judg. 11:29-40). Thirdly, you can teach men to do what is right by making disobedience painful and costly. In Leviticus 27 the Israelites are taught the folly of hasty commitments by specifying that some vows cannot be reversed, and that in those cases which can be redemption of that which was vowed will be costly. This third method, the method of Leviticus 27, we might call “economic sanctions.”

Beatrice’s “Version of Leviticus 27”

Particularly interesting in the above analysis is the continuity of economic language from the Old Testament to the Middle Ages to our own time (“ a kind of ‘credit card’ act of worship”).

In the above summary we find the notion of “economic sanctions” imposed by God in order to redeem a broken vow. In Leviticus the economic sanctions take the form of a 20% additional penalty for redeeming a broken vow. In Paradiso 5 we learn that to redeem a broken vow the old offering must be to the new offering as 4 is to 6 (verse 60). Thus a 50% penalty is imposed.

The passage on the technical or contractual nature of the pledge given to God runs from verses 19 to 63 of Paradiso 5. What follows is an overview of this section of the canto.

Of all the gifts that God gave to humans, the greatest is free will (Par. 5.19-22). When we make a pledge to God, we willingly make a sacrificial victim of our free will (Par. 5.29). As a result — given that free will is by definition the greatest good there is — we find ourselves in a situation where we have no greater good to offer in the event that we want to redeem our pledge. In the divine accounting, there is no good as great as free will that we can offer in recompense.

One could think of this issue in terms of a pawnshop. If God were running a pawnshop, and we had traded in our free will, there would be no way to redeem what we had traded in, because nothing is worth as much.

But it will turn out that there is a way. To make it possible to redeem the vow, Dante once more has recourse, as we saw in the previous canto, to solutio distinctiva. He creates a distinction, and then uses the distinction to resolve the impasse, which in this case regards how to redeem a vow.

The distinction that Dante creates is between the form or essence of a vow and the matter of the vow. The form of the vow is the contract of itself, and the matter of the vow is the thing that one has promised (e.g. poverty, chastity, etc). Here Dante effectively applies the principle of hylomorphism (forma + materia) to the definition of a vow: “Due cose si convegnono a l’essenza / di questo sacrificio: l’una è quella / di che si fa; l’altr’ è la convenenza” (Two things are of the essence when one vows / a sacrifice: the matter of the pledge / and then the formal compact one accepts [Par. 5.43-45]).

The contract itself — the “convenenza” of the above tercet — is sealed with of our free will. Hence the form of the vow, its “principio formal” or formal principle (to return to the language of Paradiso 2, which is constitutive of so much of Paradiso), can never be redeemed.

On the other hand, Beatrice continues, although it is impossible to redeem a good as precious as contract sealed with our free will, we can redeem the thing that we promised, as long as in exchange we offer God a new good that is 50% greater than the old one.

This contractual language, betokening a divinity both legalistic and fiscally severe, seems at odds with the divine principle that governs Dante’s heaven: the “amor che ’l ciel governi” (love that governs heaven) to Whom Dante addresses himself in Paradiso 1.74. What, we wonder, is at stake here for Dante?

Of primary importance for Dante, already in evidence in his story of the donna gentile in the Vita Nuova, is controlling the mutability of the will. In my essay “Errancy: A Brief History of Lo ferm voler,” cited in Coordinated Reading, I treat the issue of mutability of will as a major theme running through all of Dante’s work. In “Errancy,” I note that this issue extends from the donna gentile episode to Paradiso 5 and indeed to the end of the poem:

Dante never ceases to consider the mutability of the will. The will directed “elsewhere” from where it should be directed is a theme throughout Paradiso. The great meditation on constancy of Paradiso 5 opens with an acknowledgment of inconstancy: “s’altra cosa vostro amor seduce” (if another thing should seduce your love [Par. 5.10]). At the very end of Paradiso Dante is still conjuring the will and its consent, telling us that it is impossible not to consent to the divine light: “è impossibil che mai si consenta” (Par. 33.102). (“Errancy: A Brief History of Lo ferm voler,” p. 578)

In the same essay I also note the importance of Paradiso 5 with respect to the trajectory of the verb consentire in Dante’s work: “He uses the verb consentire for the first time in the donna gentile sonnet Gentil pensero, while in the Commedia it is concentrated in the expansive treatment of vows and the will in Paradiso 4 and 5” (“Errancy,” p. 565). And indeed, Paradiso 5 offers the only double use of consentire in the poem. The value of a vow depends on “its being made in such a way that God consents when man consents”: “s’è sì fatto / che Dio consenta quando tu consenti (Par. 5.26-7).

In sum, Paradiso 5 brings Dante back to the issues of mutability of will that he had thought about as a love poet and that he now considers within a religious context. Mutatis mutandis, the issues at core are fundamentally the same: errancy versus constancy, infidelity versus fidelity, changeability versus steadiness of purpose. In Paradiso 5 Dante stipulates all the contractual difficulties of keeping a pledge to God in order to exhort us not to make such pledges frivolously, and to be faithful: “Non prendan li mortali il voto a ciancia; / siate fedeli” (Let mortals never take a vow in jest; be faithful [Par. 5.65-65]).

Another goal for Dante in this passage is more broadly cultural or sociological, and it is to trace a genealogy of economies of faith. His purpose is to delineate the place of a Christian/New Testament economy within that genealogy.

In this canto Dante shows himself to be extremely conscious about this genealogy. Paradiso 5 is clearly engaged in a dialogue with Leviticus 27, which it echoes in many respects. Christians are held by him to an even higher standard (hence the 50% penalty) because they have greater guidance. This guidance and this support system are a source of enormous pride to Dante. Christians have the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Church to guide them:

Avete il novo e ’l vecchio Testamento, e ’l pastor de la Chiesa che vi guida; questo vi basti a vostro salvamento.(Par. 5.76-78)

You have both Testaments, the Old and New, you have the shepherd of the Church to guide you; you need no more than this for your salvation.

In Paradiso 5.81, Beatrice offers a disconcerting exhortation to Christians. She begins by telling them not to be led astray by “mala cupidigia” (evil cupidity [Par. 5.79]), thereby stating clearly that pledges can be made — and are made — for wrong and corrupt reasons. Beatrice then suggests that Jews will mock Christians who, with all the special providential assistance that is at their disposal, still fail to make their vows to God in an upright and holy fashion:

Se mala cupidigia altro vi grida, uomini siate, e non pecore matte, sì che ’l Giudeo di voi tra voi non rida! (Par. 5.79-81)

If evil greed would summon you elsewhere, be men, and not like sheep gone mad, so that the Jew who lives among you not deride you!

As her way of incentivizing Christians to achieve upright behavior and ultimately salvation, Beatrice here suggests the desire to avoid being mocked by Jews. Here Dante seems to establish a kind of unsavory “competition” within the genealogy that he has delineated from Leviticus 27 to Paradiso 5: rather than positing a conflict-free continuity with the Jewish tradition, here he establishes a somewhat rivalrous continuity, exhorting the Christians not to fall behind the Jews.

On the one hand Dante implies that the Christian economy of devotion requires higher sacrifice and commitment. On the other hand he suggests that a Jew who strictly observes the law of the Old Testament may do better than a Christian who wantonly makes vows and commutes them. And he suggests that Christians who fail with respect to Jews have much to be ashamed of.

Most of all, we need to remember that institutional devotion in human history always involves an economic and legislative dimension and the possibilities of corruption that inevitably attach to such a dimension. With respect to the Catholic Church, the corruption within its economy of faith ultimately offered Martin Luther ample ammunition in his call for reform. In Paradiso 5 Dante alludes to the very policies of annulment and commutation of vows that would later cause much scandal in the form of “dispensations”: “ma perché Santa Chiesa in ciò dispensa” (but since the Holy Church gives dispensations [Par. 5.35]).

Although stated in passing in Paradiso 5.81, we cannot ignore Dante’s harsh assessment with respect to the Jews in this canto: they are viewed not as progenitors but rather as rivals within a narrative of how best to institutionalize and negotiate with the divine. The harsh implications of Paradiso 5.81 will be picked up in Paradiso 6 and Paradiso 7, where Dante restates the charge of deicide against the Jews. This arc of canti, Paradiso 5-7, contains Dante’s most negative assessment of Jews.

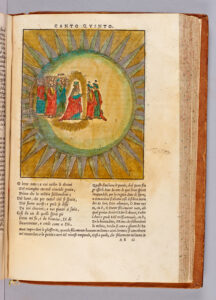

In Paradiso 5.93 the transition occurs to the second heaven. Dante is surrounded by souls and he speaks to one, asking who he is and why he is in this heaven. The soul begins to speak and speaks for the entirety of the following canto. This is Justinian, Emperor and lawmaker.

Return to top

Return to top