- Dante’s technique of rapid revisionism, here applied to Francesca’s story from Inferno 5

- An emblematic announcement of the “poetics of the new” in the opening verses of Inferno 6

- Florence is the true protagonist of Inferno 6, not Ciacco, the unknown Florentine with whom the pilgrim here speaks

- Florence and its “gluttony” for dominion and power: in Inferno 6 we see Dante engaged in the metaphorizing of sin

- The literal gluttony of Florence is invoked in the phrase traboccare il sacco in verse 50, where Florence “already overflows its sack” (Inf. 6.50)

- But the verse moves far beyond literal gluttony, as Dante signals by linking traboccare to envy: “La tua città, ch’è piena / d’invidia sì che già trabocca il sacco” (Your city, one so full / of envy that its sack has always spilled [Inf. 6.49-50])

- Why does Dante introduce the vice of envy into his discussion of gluttony?

- In this canto Dante introduces the important distinction between sinful act and underlying vice

- Florence and factional violence: Dante’s own exile from Florence in 1302 is prophesied by Ciacco

- The shame and dishonor of exile were already powerfully described by Dante in his philosophical treatise, Convivio

- The lexicon of exile and dishonor: from Boethius’ exile invoked in the Convivio as “la perpetuale infamia del suo essilio” (the perpetual infamy of his exile [Conv. 1.2.13]) to the shame (”onta”) of the exiled White Guelphs in Inferno 6

- The “divided city” of verse 61 and its implications culminate in Inferno 28, where we find the last member of this canto’s catalogue of famous Florentine citizens, all denizens of Hell: Farinata, Tegghiaio, Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo, and Mosca

- Dante’s analysis casts a net over a century of Florentine history: from the killing of Buondelmonte in 1216 to the time of Dante’s own exile in 1302

- At the end of the canto, Dante discusses the resurrection of the body, using language and doctrine that merge Aristotelianism with Christianity

- Appendix on Dante’s canzone Poscia ch’Amor (circa 1295): the canzone’s social analysis of apparently virtuous citizens who are in fact vicious is a source of Inferno 6

[1] Inferno 6 begins with an example of the poet’s technique of rapid moral recontextualization, here applied to Francesca and her lover. Employing a technique of lightning revisionism that challenges our ability to have learned from previous encounters, Dante-poet brusquely brushes aside the lush romantic aura that suffuses the encounter with Francesca, as she and Paolo are bluntly revised and reframed with new language, as “i due cognati” (Inf. 6.2). The courtly protagonists of the romantic drama depicted in Inferno 5 have been drastically revised: they are now “the two in-laws,” and it is clear that a new tone has been set.

[2] The new tone gains momentum in an emblematic announcement of the Commedia’s “poetics of the new,” as discussed in chapter 2 of The Undivine Comedy. For Dante-pilgrim alone, in Hell, there are the “novi tormenti e novi tormentati” (new sufferings and new sufferers) of Inf. 6.4. For the sinners, instead — as for the angels, but for opposite reasons, and with opposite results — there is no change, nothing is ever new. Thus the narrator states categorically in Inferno 6.9 that in Hell “measure and quality are never new”: “regola e qualità mai non l’è nova” (Inf. 6.9).

[3] As I write in The Undivine Comedy:

The pilgrim and the narrator are both committed to forward motion, to the new. Analogous to the pilgrim’s experience of “novi tormenti e novi tormentati” is the narrator’s task to “ben manifestar le cose nove” (manifest well the new things [14.7]), recalled later in his statement that “Di nova pena mi conven far versi” (Of new pain I must make verses [20.1]). In contrast to the motion of the pilgrim who, by dint of continually “passing beyond” (Noi passamm’ oltre [27.133]), will keep meeting new things until one day hell will be a memory, confined to the past absolute — “quando ti gioverà dicere «I’ fui» (when it will please you to say «I was» [16.84]) — stand both the deathly stasis of hell and the vital quies of heaven. God is “Colui che mai non vide cosa nova” (Purg. 10.94), a periphrasis whose emphatic negation echoes the description of hell where ”regola e qualità mai non l‘è nova”. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 24)

[4] Moreover, this expression of the “poetics of the new” echoes the language of Dante’s primo amico, the poet Guido Cavalcanti, who uses the phrase “La nova qualità” in his great canzone Donna me prega (49). Dante thus recapitulates the trajectory of growth beyond his lyric past as written into the discursive choices of Inferno 5:

What is interesting, in our present context, about these classic verses of comedic upward mobility is that they are derived from Guido Cavalcanti, the poet of zero mobility: Contini points out the echo of Cavalcanti’s ‘‘una paura di novi tormenti,’’ from the sonnet Perchè non fuoro a me gli occhi dispenti. So Dante has reworked Guido’s fear — his friend’s paralyzing ‘‘paura di novi tormenti’’ (fear of new sufferings) — into his own relentless forward motion; after all, the ‘‘novi tormenti’’ of canto 6 have a positive connotation for the protagonist, not being his. Rather, he revels in the resurgent strength of that unbridled present tense, used in five verbs in three verses culminating in the resounding ‘‘Io sono’’: ‘‘mi veggio intorno, come ch’io mi mova / e ch’io mi volga, e come che io guati. / Io sono al terzo cerchio . . .’’ (Inf. 6.5-7). He is not stuck with Francesca, stuck with the ‘‘novi tormenti,’’ in the space of canto 5, the space of love and death, anymore than he will be stuck with anyone else he meets along the way. And, perhaps, there is a final Cavalcantian echo, not picked up by Contini: the verse that describes the deathly stasis of hell, ‘‘regola e qualità mai non l’è nova,’’ seems to me imprinted on a periphrasis for love in Donna me prega, where love is ‘‘La nova qualità’’ (the new quality [Donna me prega 49]). If so, then — in a transformation that accurately sums up Dante’s thoughts on what Guido had to say in his great canzone — Cavalcanti’s love has become Dante’s hell. (“Dante and Cavalcanti [On Making Distinctions in Matters of Love]: Inferno 5 in Its Lyric and Autobiographical Context,” p. 99)

[5] Inferno 6 is ostentatiously different from Inferno 5. As compared to the “high” courtly and romantic lyricism of the latter half of Inferno 5, Inferno 6 is a “low” and plebeian canto, in its tone and stylistic register and even with respect to the form of punishment. The sinners of the circle of gluttony are constantly pelted by filthy and stinking rain, hail, and snow. Addressing the dismal torment of the circle of gluttony, the pilgrim notes, in a verse that is trenchantly emblematic of the transition to Inferno 6, that there is no pain more disgusting: “che, s’altra [pena] è maggio, nulla è sì spiacente” (if other pain is greater, none is more disgusting [Inf. 6.48]).

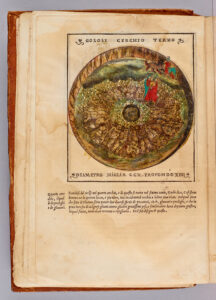

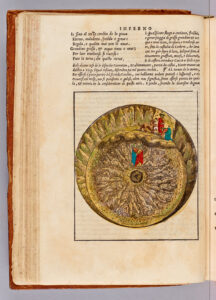

[6] Dante tells us that he has arrived in the third circle — “Io sono al terzo cerchio” (I am in the third circle [Inf. 6.7]) — where he finds the souls of the gluttons and where his interlocutor is Ciacco, whose name itself is lowly and plebeian. (in comparison, Francesca’s name is redolent of the great feudal courts of France where French romances like the Lancelot were consumed.) Most importantly, Ciacco is a Florentine who addresses Dante as a fellow Florentine.

[7] Florence here enters the Commedia. Indeed, Florence — the city-state — is effectively the main protagonist of Inferno 6, looming over the pallid and uncommunicative figure of the unknown Ciacco. The conversation between the Florentines Ciacco and Dante thus features words like “città” (city) and “cittadini” (citizens):

Ed elli a me: “La tua città, ch’è piena d’invidia sì che già trabocca il sacco, seco mi tenne in la vita serena. Voi cittadini mi chiamaste Ciacco... (Inf. 6.49-52)

And he to me: “Your city — one so full of envy that its sack has always spilled — that city held me in the sunlit life. The name you citizens gave me was Ciacco . . .

[8] By making Florence, the city, the true protagonist of Inferno 6, the canto devoted to the circle of gluttony, Dante also creates for himself an opportunity to think about sin in a metaphorical way. In what way can we say that the city of Florence is connected to gluttony? We get a sense of Dante’s metaphorical move in Ciacco’s words cited above, where he characterizes Florence as “so full of envy that its sack is already overflowing”: “piena / d’invidia sì che già trabocca il sacco” (Inf. 6.49-50]).

[9] Here we see Dante’s penchant for widening the reach of a particular sin, allowing it to “overflow the sack” of that to which it literally refers. In Inferno 5 we already saw Dante’s interest in widening the reach of the sin of lust: thus, in treating lust he ends up considering the moral failings of the code called courtly love, whose ideology permeates love poetry and romances, as well as the responsibilities of both the authors of those works and their readers. Similarly, in Inferno 6 Dante pays little if any attention to literal gluttony, which is touched on briefly in the treatment of the monstrous three-headed canine Cerberus: Virgilio throws a fistful of earth (“terra” in verse 26) into the three-headed guardian’s “bramose canne” (famished jaws [Inf. 6.27]).

[10] There follows a simile comparing Cerberus to a hungry dog who falls silent when he eats his meal, so intent is he on devouring it: “Qual è quel cane ch’abbaiando agogna, / e si racqueta poi che ’l pasto morde, / ché solo a divorarlo intende e pugna” (Just as a dog that barks with greedy hunger / will then fall quiet when he gnaws his food, / intent and straining hard to cram it in [Inf. 6.28-30]). These verses contain the canto’s only significant lexicon of excessive desire for food and its consumption, culminating in the verb divorare (devour) in verse 30. The image of Cerberus, totally engaged in devouring the clump of earth thrown by Virgilio, to the exclusion of all else, offers the canto’s only real lexical and thematic ties to the traditional sin of gluttony, defined as over-indulgence in food and drink.

[11] Instead of focusing on literal gluttony, Dante moves from literal gluttony to metaphorical gluttony. Thus, from literal gluttony he moves to the lust for wealth and power that is at the root of the factional politics that divide and destroy his city. The city’s metaphoric gluttony, quickened by envy and other vices, becomes more than gluttony: it becomes the spur to the divisive factional rivalries that were destroying the city of Florence.

[12] On multiple occasions later in the Commedia, Dante will make clear his view of Florence’s metaphorical gluttony. One such occasion is the scathing apostrophe that opens Inferno 26, where Dante indicts Florence’s gluttony for dominion and power:

Godi, Fiorenza, poi che se’ sì grande che per mare e per terra batti l’ali, e per lo ’nferno tuo nome si spande! (Inf. 26.1-3)

Be joyous, Florence, you are great indeed, for over sea and land you beat your wings; through every part of Hell your name extends!

[13] The characterization of Florence as an organism “che già trabocca il sacco” (that already overflows its sack [Inf. 6.50]) beautifully crystallizes Dante’s capacity to manage a seamless transition from the literal to the metaphorical. Literal gluttony is invoked in the verb traboccare (to spill out of, literally to spill out of the mouth of), with its root bocca (mouth). But at the same time the verse moves far beyond literal gluttony, as Dante signals by introducing a new concept into his analysis, which occurs when he tells us that Florence is “full of envy”: “La tua città, ch’è piena / d’invidia sì che già trabocca il sacco” (Your city — one so full / of envy that its sack has always spilled [Inf. 6.49-50]).

[14] Why does Dante introduce the vice of envy into his presentation of his third circle, devoted to the sin of gluttony?

[15] To answer the above question, let me begin by noting that the word invidia in verse 50 of Inferno 6 is repeated in verse 74, where envy is combined with two more vices, pride and avarice, to form the trio “superbia, Invidia e avarizia” (74). Here Dante, quite remarkably, invokes three of the seven capital vices, adding pride and avarice to the already summoned vice of envy, and letting us know that pride, envy, and avarice are composite instigators of the troubles that beset his city. The three vices are the “three sparks” that have “inflamed the hearts” of Florentines: “superbia, invidia e avarizia sono / le tre faville c’hanno i cuori accesi” (Three sparks that set on fire every heart /are envy, pride, and avariciousness [Inf. 6.74-5]).

[16] Telling us that “superbia, invidia e avarizia” — pride, envy, and avarice — are the three sparks that have inflamed the hearts of the Florentines against each other, Dante is introducing his readers to the relation of vice to sin. Sin involves the commission of a specific sinful act, which can lead to damnation if the sinner does not repent. With respect to this circle, the sinful acts for which these souls are damned are theoretically acts of gluttony, acts that are not however discussed or exemplified in Inferno 6 (Cerberus’ devouring of the mud-cake is the last example of technical gluttony offered in this canto). On the other hand, vice is not about action but about human inclinations to sinful action: it is the disposition of the soul that inclines it toward a given sin.

[17] In a kind of early behavioral psychology, Christian thinkers had identified seven capital vices (known popularly but incorrectly as the seven deadly sins): they are pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lust. Here a key point of clarification is in order: we must bear in mind that five of the seven vices — anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lust — are also the names of sins. Because we use the same words, we must be careful to distinguish: lust as a sin involves the commission of a specific sinful act (for instance, having sexual relations with one’s brother-in-law, in the case of Francesca da Rimini). The specific sinful act of adultery is triggered by the soul’s inclination to lustful behavior; that inclination is lust, the vice. The same word, “lust”, thus applies to both the sinful acts of the circle of lust and to the vice that inclines the soul toward those acts.

[18] In Inferno 6 Dante teaches us about the distinction between the sinful act and the underlying vice by telling us that, with respect to the city of Florence and its gluttony for wealth and power, there are three underlying vices: pride, envy, and avarice. Dante deploys his language with extraordinary analytic precision: as he says in verses 74-75, the vices are the sparks—“faville”—that inflame humans and cause them to act sinfully. In Dante’s metaphor, the vices are the sparks that lead to the fire, while the sins are the flames themselves.

[19] This distinction between the disposition toward the sinful act (the sparks) and the sinful act in itself (the flames) is the fundamental distinction between the organizational template of Dante’s Hell and the organizational template of Dante’s Purgatory. Hell is a place for souls who have committed sins and never repented. Purgatory, on the other hand, is a place for souls who, before dying, repented of the specific sins they committed in life, sins to which they were driven by their vices. Dante structures his Purgatory as a mountain of seven terraces, in which each of the terraces corresponds to one of the seven “deadly” vices that drive souls to sin. Thus, Dante invents an organizational template for his Purgatory that reflects the fundamental relation between vice and sin, a relation first introduced in the metaphor of sparks and flames of Inferno 6: the seven vices, purged on Mount Purgatory, are the sparks that inflame living souls to commit sinful acts.

* * *

[20] Testing the prophetic capacities of the damned, Dante-pilgrim asks Ciacco for an account of the future. He articulates his request as a three-part question about Florence:

- 1) “a che verrano / li cittadin de la città partita” (what end awaits / the citizens of that divided city? [Inf. 6.60-61]);

- 2) “s’alcun v’è giusto” (is any just man there? [Inf. 6.62]);

- 3) “la cagione / per che l’ha tanta discordia assalita” (the reason why it has been assailed by so much schism [Inf. 6.62-63]).

[21] For Dante the political thinker, the negative analysis of Florence is implicit in the lexicon of divisiveness and schism: “the divided city” — “la città partita” — of verse 61 and the “discord” — “discordia”—that assaults the city in verse 63. As we will see in the Commento on Inferno 28, which contains the bolgia of the schismatics, the highest of political values for Dante are concord and unity, while their opposites — division and discord — spell political disaster. These values are made explicit in Dante’s political treatise Monarchia, of which apposite passages are cited in the Commento on Inferno 28.

[22] In Dante’s time Florence was not a “city” in our sense, but a state, and the references to the “city” are references to the state that Dante had served as a citizen-politician and by which he was unjustly exiled. The circumstances that led to the condemnations of January and March 1302 that changed Dante’s life are rehearsed in Inferno 6 and all the major protagonists of the political dramas that savaged the city are introduced, albeit in cryptic language: the White party (pro-imperial), the Black party (pro-papal), and Pope Boniface VIII.

[23] In the fiction of the poem, in which Dante’s voyage to the afterlife takes place in spring of 1300, the condemnations of 1302 have not yet occurred. Hence Ciacco’s speech in Inferno 6 is, necessarily, presented as “prophetic”. Given that what Ciacco says in Inferno 6 is presented as literal “news” to Dante-pilgrim, his speech permits Dante-poet to choreograph a moment of great personal drama: here Dante-poet stages the experience in which Dante-pilgrim first learns that he will be exiled from his city. Dante-poet in this way narrativizes the personal pain caused by his exile from his beloved Florence, importing a biographical node of upheaval and suffering that becomes a leit-motif of his poem. He signals as well that his exile is a continuing source of pain, many years after the condemnations.

[24] To be exiled in Italy in 1300 is to be stateless: a vagabond, shamed, and dishonored. Dante had declared as much in his political treatise Convivio (written circa 1304-1307), a work in which he writes powerfully about his own condition as outcast beggar:

Ahi, piaciuto fosse al dispensatore de l’universo che la cagione de la mia scusa mai non fosse stata! ché né altri contra me avria fallato, né io sofferto avria pena ingiustamente, pena, dico, d’essilio e di povertate. 4. Poi che fu piacere de li cittadini de la bellissima e famosissima figlia di Roma, Fiorenza, di gittarmi fuori del suo dolce seno — nel quale nato e nutrito fui in fino al colmo de la vita mia, e nel quale, con buona pace di quella, desidero con tutto lo cuore di riposare l’animo stancato e terminare lo tempo che m’è dato —, per le parti quasi tutte a le quali questa lingua si stende, peregrino, quasi mendicando, sono andato, mostrando contra mia voglia la piaga de la fortuna, che suole ingiustamente al piagato molte volte essere imputata. 5. Veramente io sono stato legno sanza vela e sanza governo, portato a diversi porti e foci e liti dal vento secco che vapora la dolorosa povertade; e sono apparito a li occhi a molti che forseché per alcuna fama in altra forma m’aveano imaginato, nel conspetto de’ quali non solamente mia persona invilio, ma di minor pregio si fece ogni opera, sì già fatta, come quella che fosse a fare. (Convivio 1.3.3-5)

Ah, if only it had pleased the Maker of the Universe that the cause of my apology had never existed, for then neither would others have sinned against me, nor would I have suffered punishment unjustly–the punishment, I mean, of exile and poverty. Since it was the pleasure of the citizens of the most beautiful and famous daughter of Rome, Florence, to cast me out of her sweet bosom — where I was born and bred up to the pinnacle of my life, and where, with her good will, I desire with all my heart to rest my weary mind and to complete the span of time that is given to me — I have traveled like a stranger, almost like a beggar, through virtually all the regions to which this tongue of ours extends, displaying against my will the wound of fortune for which the wounded one is often unjustly accustomed to be held accountable. Truly I have been a ship without sail or rudder, brought to different ports, inlets, and shores by the dry wind that painful poverty blows. And I have appeared before the eyes of many who perhaps because of some report had imagined me in another form. In their sight not only was my person held cheap, but each of my works was less valued, those already completed as much as those yet to come. (Convivio 1,3-3-5, trans. Richard Lansing, on Digital Dante)

[25] In the Inferno (begun circa 1308), Dante intertwines the personal theme of his bitter exile with a moral indictment of Florence. While in the above passage from the Convivio Dante writes with resignation of the will of the Florentine citizens to cast him out — “Poi che fu piacere de li cittadini de la bellissima e famosissima figlia di Roma, Fiorenza, di gittarmi fuori del suo dolce seno“ (Since it was the pleasure of the citizens of the most beautiful and famous daughter of Rome, Florence, to cast me out of her sweet bosom) — in the Commedia those Florentine citizens are not let off the moral hook so easily. Rather they are subjected to a rigorous examination and their moral failures are unsparingly registered.

[26] Over the years, Dante elaborated a lexicon of exile. In the Convivio he cites the example of the unjust exile of Boethius. Unjust as it was, it was a cause of infamy to Boethius: “la perpetuale infamia del suo essilio” (the perpetual infamy of his exile [1.2.13]).

[27] In Inferno 6, Dante’s language for the disgraced Whites is a significant contribution to his lexicon of exile. This is the group to which he belonged and to whose fortunes he remained bound for some years after leaving Florence, before he famously turned away from all party alliances. In Inferno 6 the Whites are said to weep and take offense, experiencing shame and indignation. As a result of their treatment at the hands of the Blacks, the Whites feel “onta”, shame: “come che di ciò pianga o che n’aonti” (however much they weep and feel ashamed [Inf. 6.72]). The verb “aonti” in verse 72 is from adontarsi (in antiquity aontarsi), to feel onta.

[28] Onta, the shame and dishonor that results from social and civic injury, is a sentiment that will recur in the Commedia, for instance in the Geri del Bello episode of Inferno 29. See the Commento on Inferno 29 for a detailed discussion of onta in the context of Florentine factional violence and the practice of vendetta. The word onta is deeply sutured into the psyche of Italian communal life, as we can see by following its lexical traces in the Commedia.

[29] Fascinatingly, if we follow onta we come to the passage in Purgatorio 17 in which Dante defines each of the seven deadly vices. With respect to anger, he signals that ira is an impulse triggered by the particular cultural nexus that consists of 1) shame, 2) taking offense, and 3) consequent vengeance: onta and vendetta. Dante’s periphrasis for a generically irascible man is therefore not generic at all, but embedded in his particular culture and in the particular psychic pathology induced by his culture’s norms.

[30] Thus, Dante’s definition of ira in Purgatorio 17 includes both the verb aontare (to take offense as a result of onta, shame; the same verb used for the disgraced Whites in Inf. 6.72 cited above) and the noun vendetta. In this succinct but telling definition of anger, an angry man is one who has been injured and who — ashamed as a result of the injury received — craves vengeance:

ed è chi per ingiuria par ch’aonti, sì che si fa de la vendetta ghiotto, e tal convien che ’l male altrui impronti. (Purg. 17.121-23)

And there is he who, over injury received, resentful, for revenge grows greedy and, angrily, seeks out another’s harm.

[31] In order to express the desire for vengeance that overcomes a man who has been injured and ashamed as a result of civil unrest and violence, Dante says that “si fa della vendetta ghiotto” (Purg. 17.122): literally, such a man becomes gluttonous for vengeance. In this way, the definition of anger in Purgatorio 17 leads us back to Inferno 6 and to Hell’s circle of gluttony. Moreover, the phrase “della vendetta ghiotto” — “gluttonous for vengeance” — confirms the idea of metaphorical gluttony, of gluttony for something other than food and drink, that Dante introduces to the poem in his treatment of Florence in Inferno 6.

[32] Anger in Purgatorio 17 is defined as injury that triggers shame and offense, which in turn triggers desire for vengeance. Dante’s definition of a vice, anger, that afflicts all humanity could thus not be more profoundly and precisely embedded in Florentine culture.

[33] Much of what went wrong in Florence, what led to its being a “divided city” — “città partita” (Inf. 6.61) — can be inferred from the description of anger in Purgatorio 17. We can also formulate in reverse: in defining ira in Purgatorio 17, Dante is so deeply scarred by the cultural norms of his place and time that he extrapolates the definition of anger from the factional violence and bitter blood feuds that tore apart his own city.

[34] The moral indictment of Florence and its citizens continues in the next part of the dialogue, where Dante asks Ciacco to tell him of the whereabouts in the afterlife of specific great Florentine citizens of the generation before his: “Farinata e ’l Tegghiaio, che fuor sì degni, / Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo e ’l Mosca” (Farinata and Tegghiaio, who were so worthy, Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo, and Mosca [Inf. 6.79-80]). These are citizens whom Dante-pilgrim here describes as having had “minds bent toward the good”: “ch’a ben far puoser li ’ngegni” (Inf. 6.81).

[35] Shockingly, Dante-pilgrim is wrong in his assessment of his fellow citizens, for Ciacco replies that these Florentines are among the blackest souls of hell: “Ei son tra l’anime più nere” (They are among the blackest souls [Inf. 6.85]). Ciacco’s condemnation of citizens whom the pilgrim considers exemplary of good work — “ben far” in verse 81 — is a stunning confirmation of the moral depravity of Florence.

[36] The term “ben far” will recur as a description of Dante’s own contributions to Florence in another canto that deals with Florentine civic virtue, or the lack thereof, the canto of Brunetto Latini, Inferno 15. Brunetto tells Dante that he would have supported Dante’s “opera” (work [Inf. 15.60]) had he lived, and he characterizes Dante’s own actions with the same phrase, “ben far”, that in Inferno 6 is used for the great but damned Florentines: “ti si farà, per tuo ben far, nimico” ([the Florentine people] for your good deeds, will be your enemy [Inf. 15.64]). But whereas Dante remembers and honors the ben far of the previous generation, his own ben far will be rejected by his fellow citizens in his lifetime.

[37] Ciacco tells Dante that he will be able to see the souls of the great Florentines of the preceding generation as he proceeds through the infernal regions, and the reader should likewise pay attention to this directive. All the souls on this list of Florentines from Inferno 6 will reappear in Inferno with the exception of “Arrigo”, of whose identity we are unsure. We encounter Farinata degli Uberti in Inferno 10, among the heretics, and Tegghiaio Aldobrandi and Iacopo Rusticucci in Inferno 16, among the sodomites.

[38] The last soul on this list, Mosca dei Lamberti, who died in 1242, appears in Inferno 28, among the sowers of discord: he is blamed for having sown the division and hatred among the Florentines that led to factional division and strife in the city. The city’s factional discord was believed to have originated in the murder of Buondelmonte de’ Buondelmonti in 1216, a murder that was precipitated by Buondelmonte’s jilting of a woman of the Amidei family in favor of a Donati. Mosca’s sin was to have counseled the Amidei to take their revenge not in the form of a beating or a mutilation, but to kill Buondelmonte outright and have done with it, an act “which was the seed of evil for the Tuscans”: “che fu mal seme per la gente tosca” (Inf. 28.108).

[39] This canto’s catalogue of Florentine citizens who did bad rather than good — Farinata, Tegghiaio, Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo, and Mosca — thus will eventually culminate in Inferno 28 in a revelation about the consequent suffering of the citizenry as a whole. Mosca dei Lamberti’s act of factional violence is “mal fare” not “ben fare”; it is vicious behavior, not virtuous behavior. It is the “evil seed” that bore evil fruit for the entire Tuscan populace: “fu mal seme per la gente tosca” (the seed of evil for the Tuscan people [Inf. 28.108]).

[40] Dante’s analysis of the ills that affect “la gente tosca” thus casts a net over almost a century of evil action: he goes back to the killing of Buondelmonte in 1216 and comes forward to the time of his own exile in 1302. He includes the factional violence precipitated by Mosca de’ Lamberti in 1216 (Inferno 28) and later manifested in the warfare undertaken by Farinata, Ghibelline commander at the battle of Montaperti in 1260 (Inferno 10).

[41] All this taken together, all this nefarious and vicious behavior over many generations of Florentines, results in the “divided city” that Dante deplores in Inferno 6. In effect, Dante starts the history of Florence in Inferno 6 with the situation of contemporary Florence: the city from which he was exiled in 1302. He then works backward through time throughout the Inferno, ultimately coming in Inferno 28 to the “evil seed” that bears the bitter fruit of Inferno 6.

[42] In this first presentation of Florence in the Commedia, Dante is thus profoundly historical, laying the groundwork for showing, as he will do throughout the Commedia, that the factional violence of his day has its roots in a century of wrong-doing.

[43] Moreover, Dante’s engagement with this historical analysis is itself of long duration in his own poetic career, first tackled in the moral canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor. In Poscia ch’Amor, Dante’s analysis of the vicious behavior of Florentines includes the motif of citizens who are thought by their fellows to do good for their city, but who are in fact motivated only by desire for self-aggrandizement. This is the same motif dramatized in Inferno 6 by the pilgrim’s naïve query about the whereabouts of Florentines known for their “ben far”, and the reply that those very Florentines are deep in Hell. The Appendix contains an excerpt from an essay that treats this theme in Poscia ch’Amor and its reworking in Inferno 6.

***

[44] Finally, Inferno 6 features an important installment in the ongoing topic of Dante’s thinking on the body. This moment functions too as an installment in Dante’s stout and explicit Aristotelianism, his adherence to the philosophical tenets of the great Greek philosopher and his fascinating attempts to wed Aristotelianism to Christian eschatological beliefs.

[45] Aristotle is among the shades in Limbo, where he is accorded a remarkable honorific: he is “’l maestro di color che sanno” (the master of those who know) in Inferno 4.131. Toward the end of Inferno 6 Dante asks his guide whether the torments of Hell will be greater or lesser after the Last Judgment (Inf. 6.103-105). In reply, Virgilio instructs him to “return to your science”: “ritorna a tua scienza” (Inf. 6.106). By “tua scienza” Virgilio refers to Aristotelian philosophy and specifically to a passage in Nicomachean Ethics 10.5 on the pleasures that “perfect” and “complete” us.

[46] According to Christian theology, the human soul will reach “perfection” in the afterlife only after the resurrection of the body, when body is reunited with soul at the Last Judgment. At that point, when souls have achieved their “perfezion” (Inf. 6.110) — perfection, i.e. completion — only then will each soul experience his or her maximum of pleasure or maximum of pain:

Ed elli a me: “Ritorna a tua scienza, che vuol, quanto la cosa è più perfetta, più senta il bene, e così la doglienza. Tutto che questa gente maladetta in vera perfezion già mai non vada, di là più che di qua essere aspetta.” (Inf. 6.106-11)

And he to me: “Remember now your science, which says that when a thing has more perfection, so much the greater is its pain or pleasure. Though these accursed sinners never shall attain the true perfection, yet they can expect to be more perfect then than now.”

[47] The merging of Aristotelian principles with subsequent scholastic elaboration results in the doctrine that souls in the eschaton (after the end of time), a period that in Christian theology will be heralded by the Last Judgment, will experience more pleasure in Heaven and more pain in Hell.

[48] This passage is of great importance for a host of issues that constellate around the body and what it means to be embodied, in life and in eternity.

[49] Very important is the recognition that we are only completed, from a Christian and theological perspective, once we have been reunited to our bodies. Ultimately the belief first stated here, at the end of Inferno 6, will issue into one of Dante’s most remarkable “inventions” with respect to his journey: the idea, expressed in Paradiso, that he is graced in his vision to see the blessed in their bodies, as they will be after the Last Judgment.

[50] The recognition of the irreducible status of the body also informs some of Dante’s most extraordinary poetry, for instance Paradiso 14’s beautiful cadences on the blessed souls’ desire for their dead bodies:

Tanto mi parver sùbiti e accorti e l’uno e l’altro coro a dicer «Amme!», che ben mostrar disio d’i corpi morti: forse non pur per lor, ma per le mamme, per li padri e per li altri che fuor cari anzi che fosser sempiterne fiamme. (Par. 14.61-66)

One and the other choir seemed to me so quick and keen to say “Amen’ that they showed clearly how they longed for their dead bodies— not only for themselves, perhaps, but for their mothers, fathers, and for others dear to them before they were eternal flames.

[51] By the time we reach Inferno 6, Dante has already begun to thematize the body with respect to its status in otherworld journeys, for instance in Inferno 2’s reference to Aeneas journeying to Hades “sensibilmente”, i.e. “in the body” (Inf. 2.15). Now the poet begins to treat the issue of the “bodies” of the souls, their lack of corporeality combined with their ability to feel (in Inferno 6, the question raised is whether they will feel more pain or pleasure after the Last Judgment). All this will be an ongoing theme of the Commedia. See the Commento on Inferno 10, Inferno 13, and Inferno 25 for further discussion of the theme of the body in the Inferno.

[52] The topic of the resurrection of the body as introduced at the end of Inferno 6 thus connects to the poet’s creation of virtual bodies for his afterlife. The creation and nature of these virtual bodies are finally revealed only in Purgatorio 25, but the questions around their existence are first mooted in this canto.

[53] In Inferno 6 the travelers walk on the incorporeal shades: “e ponavam le piante / sovra lor vanità che par persona” (and set our soles upon / their empty images that seem like persons [Inf. 6.35-36]). These incorporeal shades — “vanità” as Dante calls them in Inferno 6. 36 — will seem to become quite substantial later on in the journey through Hell, especially in the encounter with the sinner whose hair Dante pulls in Inferno 32 (traitor Bocca degli Abati). We should be aware that Dante manipulates the representation of the souls’ substantiality to doctrinal effect: thus, the sinful materiality (pondus) of lower Hell gives way to the failed attempt to embrace Casella in the realm of sublimation (Purgatorio 2).

[54] Most of all, Inferno 6’s referencing of the Last Judgment and the resurrection of the body reminds us that, for Dante as for Catholic theology of the resurrection, the body is essential: not a husk to be discarded (as per the suicides of Inferno 13), but an integral part of the completed and “perfected” human being.

[55] For Dante, we only become perfect when we are reunited with our flesh.

Appendix

On Dante’s canzone Poscia ch’Amor and Inferno 6

(From: “Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia: From the Moral Canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor through Convivio to Inferno 6 and 7”)

[56] Stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor has moved in the direction of a social specificity that is absent from Le dolci rime and that is critical not only to Inferno 7, as we have seen, but also to Inferno 6, the canto of Florence. Those who throw away their wealth in stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor, like those who tenaciously cling to it, are embedded not only within an abstract Aristotelian framework but also within a civic and social world. The social world that Dante evokes is that of Florence, where the rich vie with each other to show their virtue in the form of donations to social and cultural institutions of value (much as they do at charity dinners in New York today). Doing so, their names win renown and their virtue becomes part of cultural memory, residing «là dove li boni stanno / che dopo morte fanno / riparo nella mente» (Poscia ch’Amor, 20-24).

[57] The question that Dante poses in stanza 2 of Poscia ch’Amor is the line between virtuous giving — in Aristotelian terms, liberality — and the vice of prodigality, the «gittar via del loro avere» that he condemns. In our day we have made that line easier to patrol by taking legal steps to make distinctions between social and political virtue. But that line is always somewhat permeable. Dante’s point is that it is possible, by throwing away wealth profligately, to buy virtue. In this way, he claims, we can buy a place in civic cultural memory. We can, by throwing away wealth, purchase a place among the good citizens — «li boni» — who remain in our collective memory («fanno / riparo nella mente») after their deaths («dopo morte») : «Sono che per gittar via loro avere / credon potere / capere là dove li boni stanno / che dopo morte fanno / riparo nella mente» (Poscia ch’Amor, 20-24). As nobility is mistakenly believed to be the province of those who have «antica possession d’avere» in Le dolci rime, so in Poscia ch’Amor virtue is for sale in this world, bought and sold in the «mercato d’i non saggi» (35).

[58] The construction of an afterlife is a tried-and-true method of revealing the hypocrisies of society, and in Inferno 6 Dante finds a way to scratch the itch that so irks him in the second stanza of Poscia ch’Amor. He meets a Florentine and asks three questions: 1) «a che verrano / li cittadin de la città partita» (Inf. 6.60-61); 2) «s’alcun v’è giusto» (Inf. 6.62); 3) «la cagione / per che l’ha tanta discordia assalita» (Inf. 6.62-63). After answering question 1 with an account of future events that include Dante’s own exile from his native city, Ciacco explains that there are only two just men in Florence and that they are not understood (as Dante himself, exiled, was not understood), adding that the vices that inflame Florentine hearts are «superbia, invidia» and, of course, «avarizia» (Inf. 6.74).

[59] The pilgrim then asks the whereabouts of specific great Florentine citizens whom he first names and then labels as belonging with «li altri ch’a ben far puoser li ’ngegni» (Inf. 6.81). He is inquiring as to the moral standing of men, cittadini in the language of this canto, who, he says, in life turned their ingegni toward ben far. The dead citizens whom Dante lists for Ciacco by name are citizens whose names repose in his memory. He remembers them — they live on in his memory — in a precise dramatization of the life after death sought by the profligates of Poscia ch’Amor. In Inferno 6 Dante-poet dramatizes himself remembering fellow Florentines and he dramatizes himself conferring upon those Florentines the very life after death in civic memory that the profligates of Poscia ch’Amor attempt to purchase. Perhaps they have succeeded in obtaining what they desired ?

[60] Hell has its compensations, and the Florentine citizens whom Dante naively remembers as do-gooders are revealed by Ciacco to be damned: «Ei son tra l’anime più nere» (Inf. 6.85). Thus the Florentines whom the pilgrim remembers for their ben far do not deserve to be remembered. While the non-virtuous are remembered and honored as virtuous, the virtuous are not remembered and are not honored. Maybe indeed the virtuous are exiled, as Dante was. For Florentines do not recognize the two just men who live among them : «Giusti son due, e non vi sono intesi» (Inf. 6.73).

[61] The lapidary indictment of Inferno 6, «Giusti son due, e non vi sono intesi» (73), has deep roots in Poscia ch’Amor. It accords with the sentiment of a canzone in which the poet does not know to whom to tell the truth about the courtly virtue leggiadria («tratterò il ver di lei, ma non so cui» [Poscia ch’Amor, 69]), fearing he would not be inteso. Most of all, the verse «Giusti son due, e non vi sono intesi» accords with the sentiment of a canzone that has no congedo, an absence that is a wordless testament to the absence of virtue in the community. The poet of Poscia ch’Amor has no addressees to whom to write the traditional last stanza, no one to understand his truth, for none of Dante’s fellow citizens live according to the tenets of leggiadria. All of them — «tutti» — live contrary to the teachings of leggiadria: «Color che vivon fanno tutti contra» (Poscia ch’Amor, 133). The striking last word of Poscia ch’Amor, «contra», reminds us of the similar claim in Convivio, where Dante writes that, far from being cultivators of cortesia, the courts of contemporary Italy are places where everyone practices «lo contrario» : «sì come oggi s’usa lo contrario» (Conv. 2.10.8).

[62] When Dante wrote Poscia ch’Amor and deprived it of a congedo, because «oggi s’usa lo contrario», he implicitly depicts himself as not inteso, the inhabitant of a society in which no one is capable of understanding him. In Inferno 6 he expands the Florentine circle of virtue from one to two: he moves from «Color che vivon fanno tutti contra» (Poscia ch’Amor, 133) , a formulation that carves out only the author of the canzone as one who lives according to the tenets of leggiadria, to «Giusti son due e non vi sono intesi» (Inf. 6.73), a formulation that adds one other person.

[63] After Inferno 6 and 7, the next great installment of the issues treated by Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor occurs in Inferno 15, 16, and 17. In Inferno 15 Dante meets Brunetto Latini, who translated Aristotle’s Ethics and who died in 1294, just as Dante was beginning to tackle the Aristotelian canzone Le dolci rime and the issues of citizenship treated by his mentor. The next canto introduces the Florentines Tegghiaio and Iacopo Rusticucci, two of the souls on Inferno 6’s list of apparently virtuous Florentine citizens who turn out to be damned. And Inferno 17 features Florentine usurers of the Gianfigliazzi, Obriachi, and Becchi families.

[64] Again we feel the presence of Poscia ch’Amor’s last verse, «Color che vivon fanno tutti contra». Indeed, we could say that the Florentine citizens named in these canti, along with those named in canto 6, constitute an eschatological congedo, in malo, that is now appended to the canzone Poscia ch’Amor. A virtual congedo is conjured by these names. But this virtual congedo is written in malo, because these souls are in hell. They are in hell for their failure to enact the ben far for which they nonetheless achieved renown that lives in the memories of their fellow citizens, renown that Dante-pilgrim performs and that Dante-narrator debunks. Dante-narrator scripts the pilgrim’s naïve query regarding the whereabouts of «li altri ch’a ben far puoser li ’ngegni» (Inf. 6.81), but also Ciacco’s reply that pronounces them damned. Here in hell is the reason that Poscia ch’Amor has no congedo.

Return to top

Return to top