Dante has two pressing doubts (“dubbi”) that he needs to have resolved; they press on him equally and as a result he is paralyzed and cannot proceed. In the opening sequence of Paradiso 4, Dante dramatizes his paralysis, faced with two questions that he equally desires to ask, by figuring himself as caught in the dilemma of “Buridan’s ass”: an ass that is poised between two equally distant and equally appetizing bales of hay will starve to death because reason provides no grounds for choosing one over the other. This is an ancient philosophical dilemma, already in Aristotle, which has come down to us with the name of the French philosopher Jean Buridan (c. 1301 – c. 1359/62).

The dilemma of Buridan’s ass challenges the idea of free will and is discussed by philosophers in the context of debates on free will versus determinism. Dante’s reference to it at the opening of Paradiso 4, in order to dramatize his own paralysis when faced with two equally pressing doubts, also anticipates the issue of determinism that will shortly be raised by one of these two doubts. He is curious as to whether, as suggested by the presence of souls in the heaven of the Moon, the souls in Heaven return — deterministically — to their natal stars.

Beatrice ends the paralysis — and in effect “solves” the dilemma by showing how free will can be used to choose one issue over the other — by prioritizing the pilgrim’s two dubbi, indicating which one is more dangerous and must therefore be answered first. The solution is to introduce hierarchy, thus prioritizing one doubt over the other.

The two dubbi to be discussed both derive from Paradiso 3.

It is typical of the narrative progress of Paradiso to have the discussion spurred by the pilgrim’s doubts and concerns, a method that links to the discussions of previous canti. This narrative rhythm creates a kind of terza rima writ large: in the same way that the rhyme scheme that Dante invented, terza rima, features backward glances interwoven into forward motion, so the thematic content both looks back and then moves on. We saw a similar technique in Purgatorio 15 and Purgatorio 16, in both of which a dubbio remaining in the pilgrim’s mind from Purgatorio 14 takes center stage.

Beatrice articulates the pilgrim’s two perplexities, the dubbi that fuel Paradiso 4, in verses 16-27. They are, in order of Beatrice’s articulation of them, as follows:

1. Why are the souls of the heaven of the moon held responsible for their broken vows, given that those vows were broken because of the violence to which these souls were subjected? In other words, why should the violence inflicted by someone else cause a a blessed soul to be accorded a diminished degree of beatitude in Paradise? The question is first posed thus:

Tu argomenti: “Se ’l buon voler dura, la violenza altrui per qual ragione di meritar mi scema la misura?” (Par. 4.19-21)

You reason: “If my will to good persists, why should the violence of others cause the measure of my merit to be less?”

Later in the canto Beatrice elaborates on Dante’s concern, which also involves an apparent contradiction between her words and Piccarda’s. Piccarda had indicated that the Empress Costanza always remained faithful to her monastic vows, while Beatrice observed that the commitment of the souls in the heaven of the moon was not total. Which of these two ladies — Piccarda or Beatrice — is lying? The strong verb “to lie”, mentire, is Dante’s own, in Paradiso 4.95.

The pilgrim’s second doubt, in Beatrice’s ordering, regards the issue of whether the souls of Paradise have “returned to their natal stars”. Expressed as a question about a doctrine of Plato from the Timaeus, the great Greek philosopher is here named for the only time in the Commedia:

2. Is Plato’s doctrine, which holds that souls return to the stars, true?

Ancor di dubitar ti dà cagione parer tornarsi l’anime a le stelle, secondo la sentenza di Platone. (Par. 4.22-24)

And you are also led to doubt because the doctrine Plato taught would find support by souls’ appearing to return to the stars.

Plato’s work was not yet available in the West in Dante’s time. The exception is the Timaeus, the only one of the philosopher’s dialogues to be continuously if partially available in Latin translation, with the commentary of Calcidius.

In this passage Dante is referring to the doctrine from the Timaeus according to which souls are governed by their natal stars, to which they return in between earthly incarnations. Having seen souls who were “relegated” (Par. 3.30) to the ”slowest sphere” (Par. 3.52), Dante has naturally jumped to the conclusion that souls return to the stars that determined their earthly inclinations: thus, he suspects that inconstant souls return to the moon, erotically inclined souls to Venus, martially inclined souls to Mars, and so forth.

Now we come to the question of how Beatrice resolves the impasse between the two dubbi that equally assail the pilgrim. She answers the second question first because, she says, it has more venom in it. Plato’s doctrine, she says, if taken literally, could lead to the dangerous and heretical belief in astral determinism.

Perhaps the narrator deliberately arranges to express the two dubbi in an order that will need to be rearranged in the answering. In this way, he can dramatize the need to prioritize intellectual issues on the basis of the gravity of the problem that they pose.

Returning to the second dubbio regarding astral determinism, let me offer some context with respect to the willingness of the authorities to condemn as heretics those who believe that the stars determine our choices, I give the example of the astrologer and medical doctor Cecco d’Ascoli, who was burned for heresy in Florence in 1327 (six years after Dante’s death). Although Cecco repeatedly states that he does not hold with astral determinism, the inquisitors found that he did (or pretended, for political reasons, to find that he did), and sentenced him. For further discussion of determinism, see the Commento on Inferno 7, Inferno 20, and Purgatorio 26.

Beatrice’s answer to the second dubbio is fascinating in many ways. Again, as with the discourse on the order of the universe in Paradiso 1, Beatrice’s reply begins with a question that is local and specific, and then moves to a conceptual place that much precedes it, back to first principles. And, as she did in the discussion of moon spots in Paradiso 2, Beatrice begins by shifting from the material to the immaterial, from the physical heavens to the metaphysical state of being beyond space-time that is eternity with God.

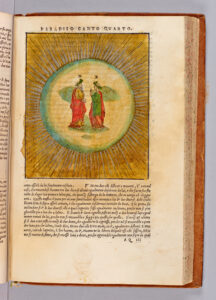

In order to make the lack of causal linkage between souls and stars crystal-clear, Beatrice explains that the souls are not really in these material heavens. They only appear in the various heavens for the sake of the pilgrim. In reality, all the souls of Paradise — from Piccarda to the highest Seraph — are together in the Empyrean:

D’i Serafin colui che più s’india, Moisè, Samuel, e quel Giovanni che prender vuoli, io dico, non Maria, non hanno in altro cielo i loro scanni che questi spirti che mo t’appariro, né hanno a l’esser lor più o meno anni; ma tutti fanno bello il primo giro, e differentemente han dolce vita per sentir più e men l’etterno spiro. (Par. 4.28-36)

Neither the Seraph closest unto God, nor Moses, Samuel, nor either John— whichever one you will—nor Mary has, I say, their place in any other heaven than that which houses those souls you just saw, nor will their blessedness last any longer. But all those souls grace the Empyrean; and each of them has gentle life—though some sense the Eternal Spirit more, some less.

So all the blessed are united in the Empyrean: “ma tutti fanno bello il primo giro.” Is there then no difference between them? Has difference been truly eliminated? Of course not. As I wrote in The Undivine Comedy: “There is no difference in paradise, but then again, as wonderfully signified by the conquering adverb ‘differentemente’, whose six syllables (five with elision) spread over most of the pivotal verse in which it is situated, there is” (p. 186).

Difference still exists; it has moved from the external to the internal, from the physical to the metaphysical. The heavens are a fiction that allows Dante to grasp what he would otherwise not be able to understand, namely the difference in spiritual attainment of each individual soul:

e differentemente han dolce vita per sentir più e men l’etterno spiro. (Par. 4.35-36)

and differently each has gentle life: some sense the Eternal Spirit more, some less.

The lesson here is: the physical differentiation that Dante sees is not real. But that does not mean that difference itself is not real. We learned in Paradiso 2 that difference is baked into the universe as a “formal principle” (“principio formal” in Par. 2.71 and 147): an essential component of reality. So, difference is real. It does not take the physical form of souls who are literally assigned to various heavens, but it takes metaphysical form as a spiritual differentiation based on the degree of the soul’s capacity to experience the divine.

Beatrice now moves in a “meta” direction, tackling representation itself. In the same way, she says, that the Bible condescends to our lowly human faculties, attributing hands and feet to God when it really is signifying something altogether different, so the Church similarly represents angels with human faces, when really angels are pure spirit:

e Santa Chiesa con aspetto umano Gabriel e Michel vi rappresenta, e l’altro che Tobia rifece sano. (Par. 4.46-48)

And Gabriel and Michael and the angel who healed the eyes of Tobit are portrayed by Holy Church with human visages.

This is a remarkable passage, because it is the straight truth: angels don’t really have human faces, but painters represent them as though they do. Similarly, a poet who has the task of representing Paradise is able, for representational purposes, to take recourse in the convenient fiction of the heavens.

Beatrice concludes her reply to the second dubbio by circling back to Plato. She explains that Plato’s doctrine has a kind of limited truth, but only as a metaphor for the influence that the stars do indeed have on humans: not determining what humans do, because humans have free will with which to resist (as we already learned from Marco Lombardo in Purgatorio 16), but influencing what we do. Understood thus, Plato’s doctrine can be understood as a way of expressing the influence that our natal stars have upon our dispositions: “S’elli intende tornare a queste ruote / l’onor de la influenza e ’l biasmo, forse / in alcun vero suo arco percuote” (If to these spheres he wanted to attribute / honor and blame for what they influence, / perhaps his arrow reaches something true [Par. 4.58-60]).

The second dubbio, the one about compulsion and the will, leads Beatrice to make a logical distinction. This turns out to be a frequent move in Paradise: when faced with an insoluble problem, she will frequently introduce a distinction in order to “solve” it. Dante uses the tool solutio distinctiva from Aristotelian logic throughout Paradiso, as I explain in the essay “Dante Squares the Circle: Textual and Philosophical Affinities of Monarchia and Paradiso (Solutio Distinctiva in Mon. 3.4.17 and Par. 4.94-114),” cited in Coordinated Reading. The essay has a particular bearing on Paradiso 4 because in the Monarchia Dante formulates solutio distinctiva as a tool for winning an argument without calling one’s opponent a liar — precisely the situation that Dante dramatizes between Piccarda and Beatrice in this canto.

In Paradiso 4 the distinction that is introduced in order to resolve the impasse between the positions of Piccarda and Beatrice is between absolute will and conditioned will (a will that is conditioned by circumstances): absolute will never consents to coercive force (and it was to absolute will that Piccarda referred when she said that Costanza never wavered in her vows), while conditioned will does consent (and it is to conditioned will that Beatrice referred when she claimed that the souls in the heaven of the moon faltered). As a result of the distinction between absolute and conditioned will, there is no contradiction between the claims of Piccarda and Beatrice after all. Both ladies are telling the truth: “sì che ver diciamo insieme” (Par. 4.114).

Just like the heavens in which the souls were only apparently arranged in a hierarchy, but really are all together and unified in the Empyrean, so the contradictory statements of Piccarda and Beatrice are revealed to be only apparently in contradiction. Conflict is avoided, just as the Monarchia theorizes will be the outcome if one uses solutio distinctiva in logical argumentation.

Conflict is nonetheless a constant presence in these canti, through the issue of violence, present in the tales of violent abduction told by Piccarda in Paradiso 3 and reinforced in Paradiso 4 by the examples of those who were able to stay absolutely constant: St. Lawrence on the grill and Mucius Scaevola who thrust his own hand into a burning fire and held it there (Par. 4.83-84; note the alternating biblical and classical examples as in Purgatorio). Paradiso 5 will offer examples of violence committed as a result of keeping a wicked vow: the biblical Jephthan and the classical Agamemnon both killed their daughters.

Fewer themes are of deeper ethical and social consequence than that of violence. Dante’s position, as staked in Paradiso 4, is unnervingly absolute, unacceptable from a modern perspective, as it is unacceptable to hold Piccarda in any way to blame for the violence inflicted upon her by her brother. Beatrice instructs the pilgrim that a will that does not wish to be overcome will never give in: “volontà, se non vuol, non s’ammorza” (will, if it wills not, is never spent [Par. 4.76]). This is a harsh doctrine, which suggests that Dante — while not condoning violent behavior — refuses to accept the status of victim of violence.

There are many absolutes in this canto, and in conclusion let us pass from the harsh absolute of “volontà, se non vuol, non s’ammorza” to the great epistemological affirmation that we find at the end of Paradiso 4.

Dante insists on the capacity of the intellect to comprehend ontological reality, the “great sea of being”: “lo gran mar dell’essere” (Par. 1.113). In the beautiful metaphor that he adopts at the end of Paradiso 4, he insists that our intellect (“nostro intelletto” of verse 125) can “repose in the truth” like a wild beast in its lair: “Posasi in esso, come fera in lustra” (our intellect reposes in it, as a wild beast in its lair [Par. 4.127]). in other words, we can indeed arrive at the comprehension of reality:

Posasi in esso, come fera in lustra, tosto che giunto l’ha; e giugner puollo: se non, ciascun disio sarebbe frustra. (Par. 4.127-129)

Mind, reaching that truth, rests within it as a beast within its lair; mind can attain that truth— if not, all our desires were vain.

To fully grasp the extraordinary force of Dante’s affirmation of our ability to reach the truth, note the syntax of the Italian. The intellect rests in the truth “as soon as it has reached it [the truth]” — “tosto che giunto l’ha” (128) — to which Dante adds “and it CAN reach it [the truth]”: “e giugner puollo” (127). The affirmation is absolute and it insists: our intellect can reach the truth.

And yet . . . The last verse of the above tercet states that, if we could not reach the truth, then all human desire would be vain. We see here the intellectual honesty that Dante cannot resist. He tells us candidly that his great affirmation must be true, because the alternative — which he has thought about, which he has allowed to enter his mind — is unacceptable.

Return to top

Return to top