Chapter 10 of The Undivine Comedy begins with two epigraphs. One is a very witty definition and performance of the rhetorical trope of enjambment, written by the poet John Hollander:

An end-stopped line is one—as you'll have guessed— Whose syntax comes, just at its end, to rest. But when the walking sentence needs to keep On going, the enjambment makes a leap Across a line-end (here, a rhyming close). (John Hollander, Rhyme’s Reason)

The other is the even more witty passage from the end of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, in which the great novelist writes that:

my readers . . . will see in the tell-tale compression of the pages before them, that we are all hastening together to perfect felicity.

Chapter 10 of The Undivine Comedy attempts to apply Austen’s insight regarding the material and mechanical dimensions of writing, in this case of ending, to a text that has persuaded generations of readers that it does not participate in mere textual strategies and that it does not have to find methods for dealing with the laws of time and narrative. But, of course, it does, and “the tell-tale compression of the pages before [us]” provided at least as much of a challenge for Dante as it did for Austen. The stakes involved for Dante are higher, given that his task is to describe the perfect felicity of beatific vision rather than the perfect felicity of romantic love.

There is much to learn, however, from Austen’s astringent comment: Dante, like Austen, was wrestling with the problems of a severely over-determined text, in which the reader knows perfectly well that “we are all hastening together to perfect felicity”. Consider the difficulty of ending a very long poem whose ending in “perfect felicity” is completely discounted and expected!

Dante evolved brilliant methods — rhetorical methods, because he is a writer, like Jane Austen — to deal with the problem of ending his severely over-determined text.

We have discussed, for instance, the Paradiso’s great ontological metaphors, which offer Dante some traction in the ongoing problem of portraying unity. Similarly, Dante develops techniques for ending the Commedia. In considering how Dante approaches the problem of ending, we will look at his reliance on the technique of the “jumping” text, a category that includes enjambment. Hence the title of Chapter 10, “The Sacred Poem is Forced to Jump”: indeed, the text “jumps” more and more as it approaches the end.

***

Where shall we posit the beginning of the end of the Commedia? I write as follows in The Undivine Comedy:

Although theoretically the beginning of the end of the poem could be located at any point along the diegetic line, including the first verse, we will begin our study of the end’s beginning rather further along, in the heaven of Saturn. (p. 221)

There are significant narrative “firsts” in the heaven of Saturn that make it a convenient point at which to begin a discussion of the beginning of the end of the Commedia.

At the beginning of Paradiso 21 Beatrice does not smile, for her smile would consume Dante. By the same token, it turns out that in this sphere “la dolce sinfonia di paradiso” (the sweet symphony of paradise [59]) has fallen silent.

Thus the pilgrim’s rising up to the “settimo splendore” (seventh splendor [13]) is marked in a new way: the absent smile and silenced symphony make this transition unlike the previous transitions.

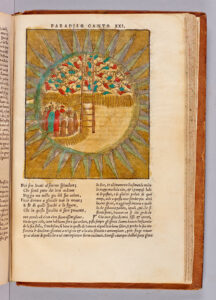

Dante sees a golden staircase leading upwards out of his sight. While a ladder is a geometric shape, composed of lines at right angles like a cross, this ladder is profoundly different from the circumscribed shapes that we have encountered in the previous heavens. The geometric circles of the heaven of the sun are circumscribed by the heaven of the sun, and the Greek cross of the heaven of Mars is also so circumscribed, by the heaven of Mars. The eagle of the heaven of Jupiter, the first pictorial rather than geometric shape to appear in Paradiso, is also circumscribed by the heaven of Justice.

But the ladder of the heaven of Saturn leads somewhere; it goes to some place that is beyond the pilgrim’s field of vision, out of his sight, out of his ken. It thus indicates a path toward a telos — to an ending — that is not implicit in the previous heavenly figurations.

In this way too the ladder is a clear marker of the beginning of the end, the end being that which we cannot see but to which this ladder leads. Up and down this ladder move the souls of the contemplatives who belong to the heaven of Saturn, and one of these souls approaches Dante.

Dante asks the soul two questions. The questions seem straightforward and not at all problematic, but the first, especially, will be cause for alarm.

- Why is it that this soul, this particular soul out of all the souls in Saturn, has chosen to draw near to Dante: “la cagion che sì presso mi t’ha posta” (literally: the reason that placed you so near to me [Par. 21.57])?

- What has caused the cessation of the music of paradise, not a previous occurrence, given that the music “giù per l’altre [rote] suona sì divota” (sounds devotedly through the other spheres [Par. 21.60]).

The soul, not yet identified, explains that it does not draw near to Dante out of any particular affect, for he feels no greater love for Dante than is felt by any other soul in this heaven:

né più amor mi fece esser più presta; ché più e tanto amor quinci sù ferve, sì come il fiammeggiar ti manifesta. (Par. 21.67-69)

The love that prompted me is not supreme; above, is love that equals or exceeds my own, as spirit-flames will let you see.

Verse 67, “né più amor mi fece esser più presta” (literally: nor did more love make me more eager), gives the measure of how far this heaven is from the affectively laden and deeply personal heaven of Mars, where Cacciaguida, full of “ardente affetto” (Par. 15.43), approached the pilgrim precisely because he does feel “più amor” (Par. 21.67) for him. Nor does Cacciaguida dissemble as to why he feels “più amor” for this particular visitor to heaven: he belongs to the same bloodline and awakens in Cacciaguida deep affective bonds as his kin and descendant.

In sharp contrast, the soul who greets Dante here in Saturn swats away all possibility of affect.

Dante then reformulates his question in a manner that is less personal, hoping to make amends for any unintended effrontery. But he makes matters worse, for the reformulation is theologically loaded in a manner that will be labeled presumptuous.

Why, the pilgrim asks, was this soul alone and specifically predestined to approach him? Noting the word “predestinata” (Par. 21.77), and remembering the apostrophe to unfathomable divine predestination at the end of the previous canto, we sense that the pilgrim is on shaky ground:

ma questo è quel ch’a cerner mi par forte, perché predestinata fosti sola a questo officio tra le tue consorte. (Par. 21.76-78)

but this seems difficult for me to grasp: why you alone, of those who form these ranks, were he who was predestined to this task.

We had just learned at the end of Paradiso 20 that divine predestination cannot be plumbed by human intellect:

O predestinazion, quanto remota è la radice tua da quelli aspetti che la prima cagion non veggion tota! (Par. 20.130-32)

How distant, o predestination, is your root from those whose vision does not see the Primal Cause in Its entirety!

In light of the above, it is not surprising that the question put by the pilgrim, as to why this soul alone was predestined to approach him, is completely off limits. As the soul, who will turn out to be the monastic contemplative Saint Peter Damian, explains: not even the highest of the seraphim would be able to satisfy Dante’s desire on this score.

Ma quell’alma nel ciel che più si schiara, quel serafin che ’n Dio più l’occhio ha fisso, a la dimanda tua non satisfara, però che sì s’innoltra ne lo abisso de l’etterno statuto quel che chiedi, che da ogne creata vista è scisso. (Par. 21.91-96)

But even Heaven’s most enlightened soul, that Seraph with his eye most set on God, could not provide the why, not satisfy what you have asked; for deep in the abyss of the Eternal Ordinance, it is cut off from all created beings’ vision.

The rhyme abisso/scisso (in bold above) has been used before, in a context that is also about testing the limits of how far humans can go in challenging the divine will and in trying to see into the “abyss” of divine predestination. Dante used the same rhyme in his desperate apostrophe to God (“Jove”) of Purgatorio 6, in which he dares to wonder whether God’s just eyes are turned away from the tragedies unfolding in Italy:

E se licito m’è, o sommo Giove che fosti in terra per noi crucifisso, son li giusti occhi tuoi rivolti altrove? O è preparazion che ne l’abisso del tuo consiglio fai per alcun bene in tutto de l’accorger nostro scisso? (Purg. 6.118-23)

And if I am allowed, o highest Jove, to ask: You who on earth were crucified for us—have You turned elsewhere Your just eyes? Or are You, in Your judgment’s depth, devising a good that we cannot foresee, completely dissevered from our way of understanding?

Now Saint Peter Damian explicitly instructs the pilgrim to take back to the mortal world the message that no one should presume to trespass as he just did:

E al mondo mortal, quando tu riedi, questo rapporta, sì che non presumma a tanto segno più mover li piedi. (Par. 21.97-99)

And to the mortal world, when you return, tell this, lest men continue to trespass and set their steps toward such a reachless goal.

Thus the poet makes a “social encounter” between the pilgrim and a soul in the heaven of Saturn into an opportunity to use the Ulyssean lexicon of trespass (“sì che non presumma / a tanto segno più mover li piedi”) and to indict human “presumption” through the use of the verb presumere. Dante’s exploitation for ideological ends of the small elements of plot that are available to him in Paradiso are notable. Here he uses the encounter between Dante and Peter Damian to engage the issue of predestination, as in the heaven of the Moon he uses the disagreement between Piccarda and Beatrice to engage the issue of absolute versus conditioned will.

The soul’s words are so prescriptive, they “prescribe” the pilgrim’s line of inquiry to such a degree, that Dante now retreats humbly to the question of simple identity:

Sì mi prescrisser le parole sue, ch’io lasciai la quistione e mi ritrassi a dimandarla umilmente chi fue. (Par. 21.103-05)

His words so curbed my query that I left behind my questioning; and I drew back and humbly asked that spirit who he was.

The humble posing of the question “chi fue” — who he was — is acceptable, and the remainder of Paradiso 21 is devoted to the introduction of the reforming Italian saint, Peter Damian.

Peter Damian now tells his story, expressing in the first person motifs that we associate with the heroic biographies of Francis and Dominic from the heaven of the sun (where however they were narrated by someone other than the protagonist of the story).

As in the discussions of the Franciscans and the Dominicans in Paradiso 11 and Paradiso 12, here in Paradiso 21 Saint Peter Damian engages the history of monasticism, moving from his life-story into the condemnation of the corruption that now infects his order.

Return to top

Return to top