Purgatorio 8 is the last canto of Ante-Purgatory, the last full canto devoted to this elegiac, nostalgic waiting place. Purgatorio 8 begins with a passage that fully captures the backward-turning affect-laden tonality of this section of Purgatorio. In order to say that it is dusk the poet says that it is that time of day that makes travelers think of home, and that makes them turn their thoughts back to the day when they bid farewell to their sweet friends. The melancholy sweetness, the sweet melancholia, of these verses is palpable:

Era già l’ora che volge il disio ai navicanti e ’ntenerisce il core lo dì c’han detto ai dolci amici addio; e che lo novo peregrin d’amore punge, se ode squilla di lontano che paia il giorno pianger che si more...(Purg. 8.1-6)

It was the hour that turns seafarers’ longings homeward—the hour that makes their hearts grow tender upon the day they bid sweet friends farewell; the hour that pierces the new traveler with love when he has heard, far off, the bell that seems to mourn the dying of the day...

The narrator then moves on to recount a ritual event in which the temptation of Adam and Eve (“la prima gente” of Purgatorio 1.24) is performed for the saved souls in the Valley of Princes. There is, however, a radically different outcome to this ritual from that which originally occurred in the Garden of Eden: angels appear with swords and drive away the tempter snake.

The angels’ garments are the color of “leaves just-now-born” (“fogliette pur mo nate”), a color that we can try very hard to see in the early spring, before the leaves darken, as they begin to do almost immediately:

Verdi come fogliette pur mo nate erano in veste, che da verdi penne percosse traean dietro e ventilate. (Purg. 8.28-30)

Their garments, just as green as newborn leaves, were agitated, fanned by their green wings, and trailed behind them.

I call this performance a ritual event because it occurs, as far as we can tell, every evening, affording these souls an opportunity to meditate continuously on the temptation that they were able to defeat. It is, effectively, a kind of evening Mass that reminds the souls what they overcame to achieve salvation. Binding the pilgrim with a reed at the foot of Mount Purgatory in Purgatorio 1 is also ritualistic behavior, but it is focused on an individual. This is a ritual that, like a Mass in church, is engaged in by a group at the same time every day.

The inclusion of a ritual is important: it underscores the ecclesiastical nature of Dante’s Purgatory and it also constitutes a narratological challenge for the poet. How is a poet to narrate ritual action that repeats, in the same format, over and over in time? The ritual is signposted by the poet with an address to the reader (Purg. 8.19-21). For some of the narrative complexities raised by the representation of this ritual, see The Undivine Comedy, pp. 85-86.

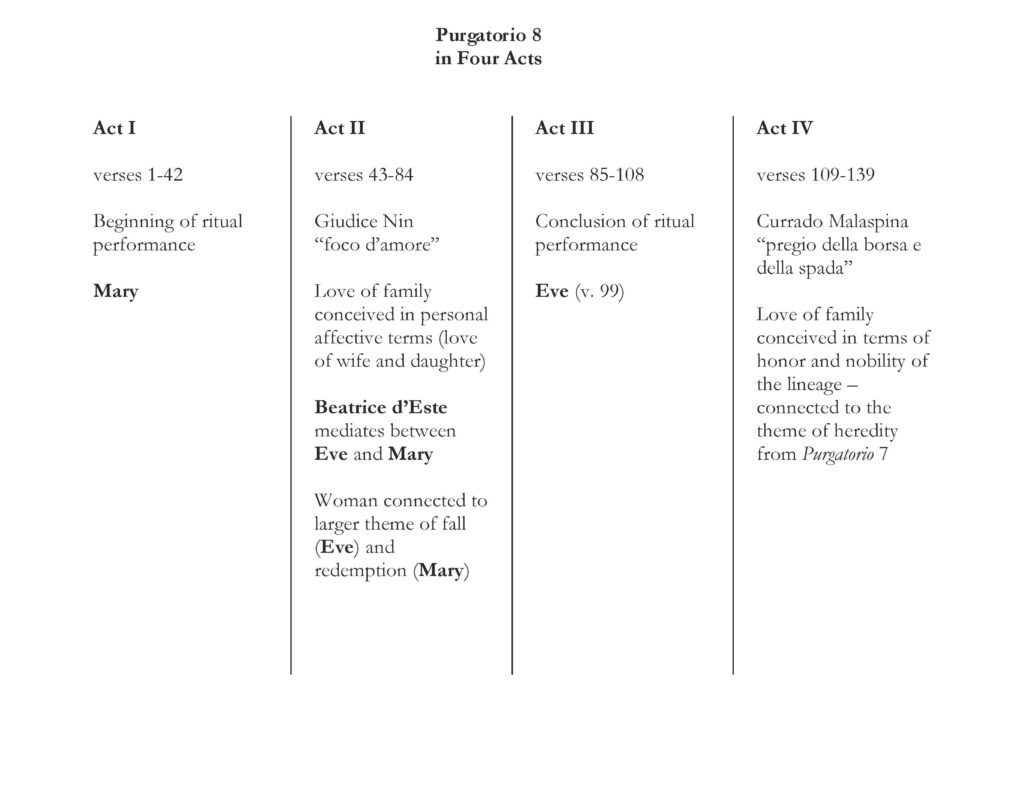

The complex narrative structure of Purgatorio 8 interweaves the ritual of the angels and the snake with two encounters: an encounter with Nino Visconti and an encounter with Currado Malaspina. The narrator begins to recount the ritual, focusing on the angels who guard the Valley (Purg. 8.1-42); he then interrupts to narrate the meeting between Dante and his friend “Giudice Nin” (43-84); he then returns to the account of the ritual and completes the story (85-108); and finally he narrates the meeting of Dante with Currado Malaspina (109-39). We could outline the canto in the following manner:

Nino Visconti, grandson of Ugolino della Gherardesca, hailed by Dante as “giudice Nin gentil” (Purg. 8.53) — “Noble Judge Nino” — is another in the fraternity of friends whom Dante meets in Purgatory. As occurred when Dante met Belacqua, Dante signals his relief at his friend’s salvation:

Ver’ me si fece, e io ver’ lui mi fei: giudice Nin gentil, quanto mi piacque quando ti vidi non esser tra ’ rei! (Purg. 8.52-54)

He moved toward me, and I advanced toward him. Noble Judge Nino—what delight was mine when I saw you were not among the damned!

In the above outline of the canto’s four narrative sections, I have added only the basic thematic connectors between sections; there are many other thematic recalls between the four narrative building blocks.

Women and gender issues abound in this canto, on a spectrum that runs from Mary to Eve. Featured, in between those extremes, are the female relatives of Nino Visconti, in particular his remarried wife Beatrice d’Este. Nino indulges in essentializing regret for the fickleness of females, who forget a man once he is no longer present to touch her:

Per lei assai di lieve si comprende quanto in femmina foco d’amor dura, se l’occhio o ’l tatto spesso non l’accende. (Purg. 8.76-78)

Through her, one understands so easily how brief, in woman, is love's fire—when not rekindled frequently by eye or touch.

In response one could cite Shakespeare’s “Sigh No More” from Much Ado About Nothing (“Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more, / Men were deceivers ever”) as well as Anne Elliot’s speech on the greater fidelity of women at the end of Jane Austen’s great novel, Persuasion.

The question of what we inherit from our parents — and what makes us noble — is kept alive in this canto, having been initiated in the previous canto. It now finds expression in a discussion of the noble traits of the Malaspina family.

The encounter with Currado Malaspina highlights Dante’s abiding interest in the virtues of cortesia. Dante praises the Malaspina family, which will host him during his exile, saying that they possess the two great chivalric virtues, demonstrating both “the glory of the purse and of the sword”: “[il] pregio de la borsa e de la spada” (Purg. 8.129). Dante’s celebration of the Malaspina family shows us his nostalgic entertainment of the idea of a certain kind of feudal nobility, endowed with chivalric pregio (Occitan pretz) as displayed by their liberality and courage. The Malaspina family embodies pregio not only as warriors but in their liberality — in their enlightened handling of their wealth. See the Commento on Inferno 16 for Dante’s evolving ideas on society and wealth management, and also the essay “Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

The Malaspina family come by their virtues as a result of the good offices of both “habit” and “nature”: “Uso e natura sì la privilegia” (Habit and nature so privileges them [Purg. 8.130]). In other words, they have good habits and are also well disposed by nature, through heredity. Dante is in this way engaging in a version of what we would call a Nature versus Nurture (habit) debate. Through the distinction between uso and natura, Dante touches on the theme of heredity broached in the previous canto, and gives us an example of the “rare” passing on of virtue from father to son.

Return to top

Return to top