Purgatorio 18 is a very important canto, particularly to those readers who cherish Dante’s origins as a lyric poet, which Dante-poet here evokes in loving detail. He not only evokes his lyric origins, but makes clear once more — as he already had in Inferno 5 — that the lyric tradition is ethically challenged in one absolutely fundamental tenet. Love is not an irresistible force that removes our free will, as love poets have claimed since time immemorial: think of Vergil’s Eclogue 10 with its “omnia vincit amor, et nos cedamus amori” (love conquers all things, and we too succumb to love).

This view is the default view of the lyric tradition that Dante embraced in his youth, and it is a view that he himself expressed. One famous example of Dante’s expression of the deterministic position with respect to love is the late sonnet Io sono stato con Amore insieme, written circa 1306. Here the poet declares that in the arena of Love, free will is never free, and counsel is vain: “Però nel cerchio della sua palestra / libero albitrio già mai non fu franco, / sì che consiglio invan vi si balestra” (Thus within his arena’s bounds free will was never free, so that counsel looses its shafts in vain there [Io sono stato, 9-11; Foster-Boyde trans.). The “consiglio” (counsel) of verse 11, which in the context of the sonnet Io sono stato is completely ineffective, will become in Purgatorio 18 the “power that gives counsel”, namely free will: “innata v’è la virtù che consiglia” (innate in you is the power that gives counsel [Purg. 18.62]).

Reiterating the lesson learned in the previous canto, whereby love is the root cause of all human behavior, of all our actions and works (“operare” in Purgatorio 18.15), both good and evil, Dante-pilgrim now asks Virgilio to explain love:

Però ti prego, dolce padre caro, che mi dimostri amore, a cui reduce ogne buono operare e ’l suo contraro. (Purg. 18.13-15)

Therefore, I pray you, gentle father dear, to teach me what love is: you have reduced to love both each good and its opposite.

The question is “che mi dimostri amore”: show me what love is, teach me about love. There is no better primer on the subject of love than the one provided by the great tradition of the courtly love lyric, a tradition that is seriously explored in the Commedia, and particularly in Purgatorio. The classical Roman Virgilio therefore offers an explanation of love that is rooted in the vernacular lyric tradition that began with the Occitan poets in the South of France and moved to Italy via the Sicilian poets in the court of Frederic II. This is a tradition that we first encounter in this commentary in glossing Inferno 2 and Inferno 5 and that Dante will feature in high relief in Purgatorio 24 and Purgatorio 26.

Virgilio explains as follows. The soul is created quick to love — “creato ad amar presto” (19) — and is susceptible to that pleasure — “piacere” (21) — that awakens within it the capacity to love, thus moving the soul from potency (with respect to love) to act: “atto” (21). As soon as it is activated, the soul responds to that which pleases it:

L’animo, ch’è creato ad amar presto, ad ogne cosa è mobile che piace, tosto che dal piacere in atto è desto. (Purg. 18.19-21)

The soul, which is created quick to love, responds to everything that pleases, just as soon as beauty wakens it to act.

In the above tercet, the Italian translated as “the soul responds to everything that pleases” is “ad ogne cosa è mobile che piace” (20): literally, Dante is saying that the soul “is mobile with respect to (“è mobile a”) everything that pleases it. The choice of the expression “è mobile a” tells us that the soul that is activated to love moves toward — “is mobile with respect to” — all things that please it. In other words, there is spiritual motion involved in the act of love.

I stress the construction “è mobile a” to remind the reader that, for Dante, motion is essential to love: “amor mi mosse” (Love moved me) says Beatrice in Inferno 2, verse 72. And he is about to gloss that earlier statement by telling us that desire is spiritual motion, “moto spiritale” (Purg. 18.32).

Let us return to Dante’s explanation of the process of “falling in love”. In the next tercet, the poet describes how our cognitive faculty (“apprensiva” [22]) takes the image (“intenzione” [23]) of a “true being” — “esser verace” (22) — and unfolds that image within the soul: “dentro a voi la spiega” (23).

Very important is the fact that the image of the beloved that we unfold within ourselves is the image of an “esser verace”: a “true being”, a real ontological being that exists in the external world, independent of our ability to know it or desire it. An entire ethics is unleashed from the recognition that the beloved has ontological status and is not merely, as she is in much lyric poetry, a narcissistic mirage in the image of the lover. Dante’s “ethical turn”, his infusion of ethics into the lyric, a move that I have discussed at length in my commentary on his early lyrics and in later essays like “Errancy: A Brief History of Lo Ferm Voler”, is signalled in the phrase “esser verace”.

We return again to the process of falling in love. Effectively, our cognitive faculty “takes a picture” of a pleasurable object and then posts that image on an internal memory board, recreating the object internally:

Vostra apprensiva da esser verace tragge intenzione, e dentro a voi la spiega, sì che l’animo ad essa volger face (Purg. 18.22-24)

Your apprehension draws an image from a real object and expands upon that object until soul has turned toward it

The apprensiva acts in three distinct ways in the above terzina, and is the subject of three distinct verbs: “tragge”, “spiega”, and “face”. The three actions of the apprensiva are: 1) it draws an image from a real object; 2) it unfolds that image within the soul; 3) it causes the soul to turn toward that image. This third action describes motion of the soul and thus picks up on “mobile” in the previous tercet, now exchanging mobile (from muovere) to volgere: “sì che l’animo ad essa volger face” (so that it causes the soul to turn toward it [24]).

The verb volgere, “to turn”, will be picked up and amplified in the past participle “rivolto”, “to have turned”, in the next terzina. Volgere is a verb of motion, specifically of turning toward an object, hence of conversion. It is important to understand that, in the fundamental sense of the word, one can “convert” to the wrong object, as well as to the Right One.

The next two steps in the behavior of the soul as it “falls in love” are very precisely delineated, and involve 1) the turning of the soul, an action already stipulated in verse 24, and now repeated and confirmed as having occurred by the past participle “rivolto” of verse 25; and 2) the bending or inclining of the soul. We know that the animo/soul of verse 24 has “turned” toward the image: “volger” in verse 24. That turning is a prerequisite of such importance that the poet repeats it in the past tense — “rivolto” (25) — before moving on to the next step in his analysis. If, having turned toward the image of the pleasing object, the animo/soul should incline toward it, then that inclination — “quel piegare” (26) — is love:

e se, rivolto, inver’ di lei si piega, quel piegare è amor, quell’è natura che per piacer di novo in voi si lega. (Purg. 18.25-27)

and if, so turned, the soul tends steadfastly, then that propensity is love — it’s nature that joins the soul in you, anew, through beauty.

Love is thus the soul’s inclination toward another ontologically real being.

The soul has now, in this manner described above, been seized by love: it is taken, “preso” in verse 31. The past participle preso in Purgatorio 18.31 is a quintessentially lyric word, used in the incipit of Dante’s sonnet Ciascun’alma presa e gentil core and by Francesca da Rimini, echoing the lyric usage, in Inferno 5. The past participle of prendere, to take, preso means “taken”. It is a word that signals determinism, compulsion, lack of free will: if the soul is “taken”, does it act freely? This is a question that is not dealt with immediately, but it is signalled by the word preso, and we will come to it in due course.

Seized by love, conquered by love, the soul enters on a quest of desire. Desire, Dante tells us, is spiritual motion: “disire, / ch’è moto spiritale” (Purg. 18.31-32). The soul sets off on its quest to possess the beloved, and never rests until the beloved object gives it joy:

così l’animo preso entra in disire, ch’è moto spiritale, e mai non posa fin che la cosa amata il fa gioire. (Purg. 18.31-33)

so does the soul, when seized, move into longing, a motion of the spirit, never resting till the beloved thing has made it joyous.

This definition of desire as spiritual motion, as that which moves us along the path of our life (the “cammin di nostra vita” in the first verse of the Commedia), is the bedrock of the analysis of The Undivine Comedy, as you can see from the opening section of Chapter 2, culminating on page 26.

But the pilgrim has a rejoinder for his guide. Primed by the lesson that he recently learned from Marco Lombardo on the freedom of the will, he sees a pitfall in the description of the soul in motion, pursuing the beloved object until it gives the soul joy. If love is a natural response to something that is proffered to us from outside, how can there be merit in choosing a good or bad object of desire (Purg. 18.43-45)? In other words, how can we be blamed if we choose to love a bad object?

Here we see the lyric tradition collide with ethics: what happens if we incline in love toward something bad? Are we justified in saying that love forced us (as Francesa says)? Or do we still have a choice, even in what Dante — in the deterministic sonnet Io sono stato — calls the “palestra d’amore” (Love’s arena)? Is love deterministic, as poets have averred forever? Does determinism therefore exist? Is the fault really in our stars after all?

The collision that Dante dramatizes in Purgatorio 18 is one that he lived over the course of his youth as a poet, as he worked out the ethical implications inherent in the courtly love lyric. The story of how he moved from the answer that he gives to Dante da Maiano in the early 1280s, when he says that there is no way to oppose love, to the poet who can dramatize the problem itself in Purgatorio 18 is the story that I tell in my commentary on his lyric poetry. This is not an issue that Dante ethicizes only now, in the Commedia, for the first time.

Rather, Dante here dramatizes the process of bringing an ethically-attuned philosophical mind into confrontation with the lyric tradition, an experience at the heart of his own intellectual formation.

The pilgrim’s question leads to a discussion of free will (see Marco Lombardo’s discourse in Purgatorio 16). Virgilio uses the beautiful metaphor of free will as that which guards the threshold of assent:

Or perché a questa ogn’altra si raccoglia, innata v’è la virtù che consiglia, e de l’assenso de’ tener la soglia. (Purg. 18.61-63)

Now, that all other longings may conform to this first will, there is in you, inborn, the power that counsels, keeper of the threshold of your assent.

As in the sonnet Per quella via che la Bellezza corre (circa 1292), free will metaphorically stands guard at the doorway of the mansion of the soul and prevents a wrong desire from entering. It follows that, if a wrong desire should cross the threshold of the door of the soul and gain entry, our free will has failed to deploy and to combat it.

This passage also leads to one of Virgilio’s confessions of his limitations as guide, and to his conjuring of Beatrice as the one who can better answer Dante’s query:

La nobile virtù Beatrice intende per lo libero arbitrio, e però guarda che l’abbi a mente, s’a parlar ten prende. (Purg. 18.73-75)

This noble power is what Beatrice means by free will; therefore, remember it, if she should ever speak of it to you.

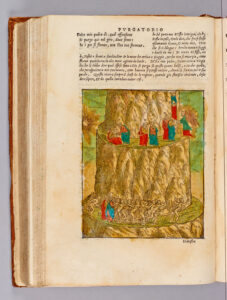

The latter half of Purgatorio 18 is devoted to the accidiosi, those whose sin is accidia: a kind of moral sloth, despair, lack of commitment to the good. Remarkably, Dante compresses the whole fourth terrace into half a canto. The baseline measure for a terrace is provided by the first terrace, pride, which takes up three canti: Purgatorio 10-12.

The compressed narrative is a textual analogue to the “holy haste” that motivates the once negligent and tardy souls on this terrace. No longer slow and torpid in their pursuit of love of the good, they are so busy running that they cannot stop to talk to Dante. The souls call out the examples of zeal and of its opposite, moral torpor, as they run by. The result is that there are no encounters with souls, no conversations that require textual expenditure, and the poet “runs through” the terrace of sloth.

Return to top

Return to top