Purgatory consists of seven ledges or terraces carved into the rockface of the mountain, each of which is devoted to purging one of the seven capital vices: pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, lust. I refer to “vices” rather than “sins” because, properly speaking, vices are the inclinations that spur humans to engage in sinful action (see the discussion in the Commento on Inferno 12). In other words, vices are psychological inclinations of a given soul, the personality traits that goad us to sin, whereas sins are specific actions. Sin, unrepented, is punished in Hell. Purgatory is the realm where souls who have repented their sins and are saved now purge themselves of the inclinations that caused the sins for which they repented, thus gaining admittance to this place and to this process.

In the Commento on Purgatorio 1, I discuss the fact that Purgatory was a relatively recent doctrinal acquisition compared to Heaven and Hell and therefore much less developed in both theological and popular conception. As a result, Dante enjoyed great freedom in creating his Purgatory. We have already seen that he devotes the first nine canti of Purgatorio to a waiting area where souls who are not yet ready to begin the process of purgation on the seven terraces prepare themselves.

Once we reach the terraces of “Purgatory proper”, Dante has new inventions for us. He makes the experience of reading Purgatorio markedly different from the experience of reading Inferno by creating a uniform template that is imposed onto each of the seven terraces.

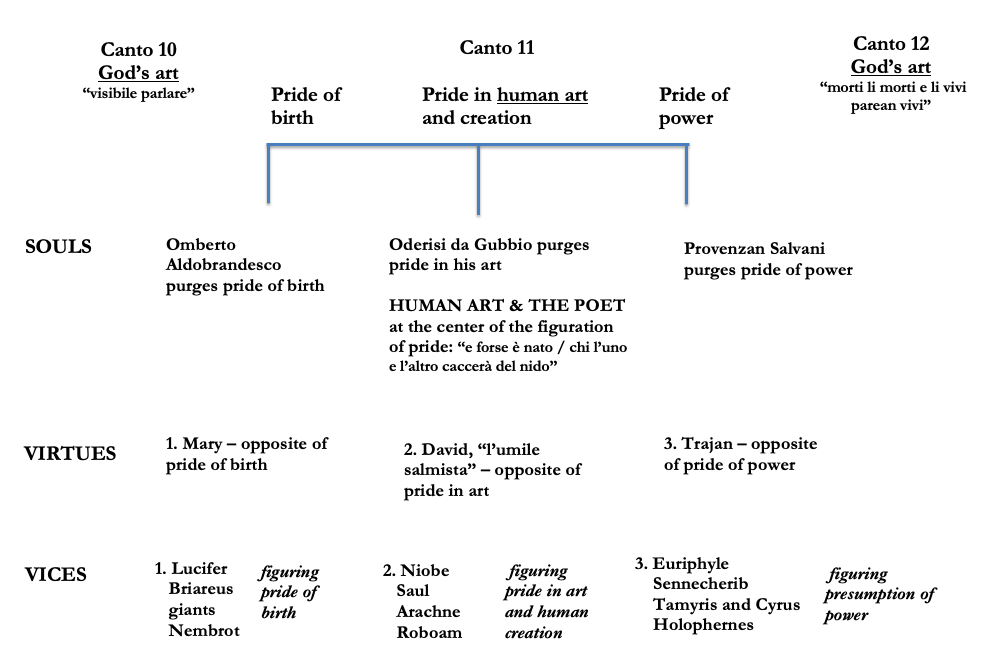

Dante treats the first terrace of Mount Purgatory, the terrace of pride, as a formal teaching tool. He divides his major narrative building blocks by canto, thus making them discrete and recognizable: the biblical and classical examples of humility, the virtue that corresponds to the vice being purged, are allocated to Purgatorio 10; the encounters with purging prideful souls are allocated to Purgatorio 11; the biblical and classical examples of the vice being purged, followed by the components that consistently signal departure from a terrace (the encounter with an angel who removes a P from Dante’s brow and the recitation of a Beatitude), are allocated to Purgatorio 12.

As we progress in Purgatorio, these narrative elements, common to each of the seven terraces, will not again be so neatly and usefully segregated. A narrative feature that aligns with the beginning of a terrace (the examples of the virtue) may be situated at the end of a canto (e.g., the examples of meekness in Purgatorio 15), while a narrative feature that aligns with the end of a terrace (the encounter with the angel) may be situated toward a canto’s beginning (e.g. the angel in Purgatorio 17).

Dante’s implied message to the reader suggests that we take the lay-out of the first terrace as a reference-point: we should get our bearings here, he seems to be telling us, where the purgatorial terrace is parsed by the canto delimiters in such a way as to render its narrative elements and their sequential unfolding extremely clear. We need to hold on to that reference-point as we navigate the subsequent six terraces, where the same liturgically repetitive narrative building blocks are artfully, and at times confusingly, arranged.

As noted above, the template for each terrace of Dante’s Purgatory involves: 1) examples of the virtue that corresponds to the vice being purged (these examples of virtue always begin with a story from the life of Mary, followed by biblical and classical vignettes); 2) encounters with souls; 3) examples of the vice being purged; 4) the recitation of a Beatitude and an angel who takes a “P” off the pilgrim’s brow at the end of each terrace and speeds him on his way:

We remember the straightforward quality of the first circles of Hell, with a canto assigned to each circle: one canto for Limbo (Inferno 4), one canto for lust (Inferno 5), and one canto for gluttony (Inferno 6). In the same way, on the first terrace of Purgatory the components of the template are arranged in the clearest possible way, one component to a canto: examples of the corresponding virtue (humility) in Purgatorio 10, encounters with souls in Purgatorio 11, and examples of the vice being purged (pride) in Purgatorio 12. Below is a chart of the structural components of Purgatorio 10-12.

As he moves on from the first terrace, Dante finds ways to create variatio around this fixed template, and thus to create a reading experience that is particular to Purgatorio. The repetition of the template confers a repetitive, ritualistic, and liturgical nature to the narration of Purgatorio, absent from the narration of Inferno. The anchoring effect of the repeated template is especially interesting and valuable in Purgatorio, the one cantica where everyone is on the move, thus adding a sense of reliability and steadiness to a domain that otherwise is all fluidity.

***

The travelers enter through the “porta / che ’l mal amor dell’anime disusa” (Purg. 10.1-2): literally, the “gate that the evil love of the souls dis-uses”, the gate that the souls’ evil love — “mal amor” — renders less used than it should be. In other words, our evil love, our propensity to love the wrong things, to love aberrantly, causes us humans to fail to use this gate, to fail to reach Purgatory. And, in the third verse of the opening tercet, we learn that this happens because our evil love is capable of making the twisted way seem like the straight way: “perché fa parer dritta la via torta” (Purg. 10.3).

The first issue that we need to unpack is the concept of “evil love”: “mal amor”. Augustine provides the language of bonus amor versus malus amor that is so important for Dante’s Purgatorio, the most Augustinian of Dante’s three realms. For instance, in City of God 14.7 Augustine writes that “a right will is good love and a wrong will is bad love”: “recta itaque voluntas est bonus amor et voluntas perversa malus amor”. The concept of malus amor points forward to Dante’s analysis of vice in Purgatorio 17, where he shows that all human behavior — good or evil — is rooted in love. Bad behavior can be rooted in love because we can love in the wrong way, or love the wrong objects.

We come back to the issue of human errancy and to the very beginning of the Commedia: at the beginning the pilgrim finds himself in a dark wood, where the “straight way” (“dritta via” in the poem’s third verse) is lost. Now we learn that our misplaced love causes the non-straight way, the twisted way — the “via torta” of Purgatorio 10.3 — to appear to be straight. This concept, that we can mislead ourselves into believing that the twisted way is the straight way, will be a theme of Purgatorio, most dramatically reprised in the dream of the Siren in Purgatorio 19.

The second issue that we need to unpack is the verb disusare, which forcefully communicates the importance of habit — uso for Dante — in the pursuit of virtue. Evil love dishabituates us from following the straight path. Our habits need to be retrained. Purgatory is the place where humans are rehabituated to the straight path. Once they finish the process of purgation, the crooked path will never again be confused with the straight path.

The entrance to the gate of Purgatory, the beginning of “Purgatory proper”, is thus inaugurated with a tercet that reprises the most fundamental themes of the Commedia.

* * *

Dante and Virgilio climb onto the first terrace of Purgatory, the terrace of pride, where they are confronted with marvelous artwork in the form of engravings sculpted into the mountain.

Much of the terrace of pride will consist of Dante’s descriptions of the artwork that he sees. These descriptions are lengthy ekphrases: ekphrasis is the rhetorical trope whereby one form of representation, such as poetry or verbal representation, reproduces another, in this case sculpted engravings. Ekphrasis is an inherently metapoetic trope, in that it is a trope that enacts a meditation on representation itself, as one form of representation is charged with the attempt to reproduce another form of representation.

The intensely metapoetic nature of the terrace of pride is analyzed at length in Chapter 6 of The Undivine Comedy; indeed, Purgatorio‘s terrace of pride is one of only two units to receive a chapter to itself in a book that is a metapoetic analysis of the Commedia (the other is chapter 9, on the metapoetic implications of the biographies of Saint Francis and Saint Dominic). In Chapter 6, “Re-Presenting What God Presented: The Arachnean Art of the Terrace of Pride,” I consider the paradoxes inherent in putting oneself in the position of “re-presenting” God’s art in one’s human language. What does it mean for the poet to rival God as artifex in the context of a treatment of humility?

Onto the marble sides of the mountain are engraved three scenes, re-presented so wondrously that they seem not “re-presented” but “presented”: in other words, they seem not art but life. They are so lifelike that not only the greatest of classical sculptors, Polycletus, would have been defeated by their artistry, but nature herself would be put to scorn:

esser di marmo candido e addorno d’intagli sì, che non pur Policleto, ma la natura lì avrebbe scorno. (Purg. 10.31-33)

was of white marble and adorned with carvings so accurate — not only Polycletus but even Nature, there, would feel defeated.

Dante instructed us with respect to the hierarchy of mimesis/imitation at the end of Inferno 11, where we learned that God is Artifex, that nature imitates God, and that human art imitates nature. Therefore, Dante has already informed us indirectly that these engravings are God’s work, since only God is a superior artist to nature.

Dante comes back to defining the miraculous nature of the engravings later in Purgatorio 10, where he states explicitly that they are God’s handiwork, and gives them the wonderful label “visibile parlare”: visible speech (Purg. 10.95). Dante has effectively come up with the idea of “moving pictures”, as cinema was called in its early days. These engravings are so lifelike that they are capable of making speech itself visible to the onlooker. Only God, it turns out, can produce “esto visibile parlare”, this visible speech:

Colui che mai non vide cosa nova produsse esto visibile parlare, novello a noi perché qui non si trova. (Purg. 10.94-96)

This was the speech made visible by One within whose sight no thing is new — but we, who lack its likeness here, find novelty.

These engravings depict three examples of humility: the virtue that is the antithesis of the vice being purged on this terrace. The first example is from the life of Mary, and recounts the Annunciation; the second, also biblical, is the story of King David, “the humble psalmist” of Purg. 10.65, who dances before the Ark of the Covenant and scandalizes his proud wife; the third example is classical and recounts how the emperor Trajan is moved by the needs of a poor widow to interrupt his campaign. See The Undivine Comedy, pp. 123-26, for the narrative techniques used in representing these representations.

These examples spur the purging souls to emulate humility, and in this way — as announced in the canto’s second verse — the examples work to “dishabituate” the souls from the “evil love” of pride. How pride can be considered a perverted form of love is something we will learn in Purgatorio 17.

Toward the end of Purgatorio 10 the pilgrim sees shapes coming toward him bent over under grievous weights. These are the purging prideful. Now that we are in Purgatory proper each vice is punished not just by the duration of time that is spent purging it but also by a specific physical torment: the prideful souls on this terrace are bent over beneath heavy stones, whose weight is greater or lesser depending on the degree of pride to be purged.

Once more pride is connected to artistry, as the bent souls are compared to sculpted caryatids, stone figures on medieval cathedrals whose knees are drawn up to their chests (Purg. 10.130-32).

Return to top

Return to top