Paradiso 12 begins with a great example of the “anti-narrative”/“lyrical” language that Dante deploys in Paradiso in opposition to his discursive/logical/“narrative” language. I describe the narrative texture of Paradiso as the poet’s careful and considered oscillation between these two modes in The Undivine Comedy (pp. 207-8):

The openings of both cantos 12 and 13 are lyrical explosions dedicated to impressing upon us the unity of the two circles, a unity that has just been shattered by the preceding biographies, with their relentless privileging — and denial — of difference. When Dante tells us that difference does not exist, as in the introductory sections of the vite, he creates it; when he wholeheartedly wishes to create the illusion of lack of difference, he resorts not to statements about its presence or absence but to another kind of writing, one that does not (insofar as is humanly possible) make distinctions. In these passages, the text becomes an incandescent swirl of language, as the poet layers simile within simile, intending thus to disconnect the logical connectors of discourse à la St. Thomas.

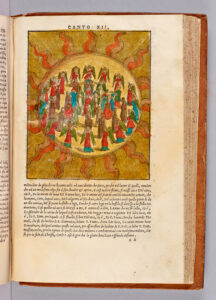

The above analysis then offers as example of the anti-narrative mode the verses (Par. 12.10-21) that describe the joyous dance of the second circle of wise men, which now appears:

Come si volgon per tenera nube due archi paralelli e concolori, quando Iunone a sua ancella iube, nascendo di quel d’entro quel di fori, a guisa del parlar di quella vaga ch’amor consunse come sol vapori . . . . . . . . . . . . . così di quelle sempiterne rose volgiensi circa noi le due ghirlande, e sì l'estrema all'intima rispuose. (Par. 12.10-15, 19-21)

Just as, concentric, like in color, two rainbows will curve their way through a thin cloud when Juno has commanded her handmaid, the outer rainbow echoing the inner, much like the voice of one—the wandering nymph— whom love consumed as sun consumes the mist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . so the two garlands of those everlasting roses circled around us, and so did the outer circle mime the inner ring.

The lead soul of the second circle begins to speak in verse 31 and explains that the previous eulogy of St. Francis calls for a corresponding celebration of St. Dominic. He therefore eulogizes the life of Saint Dominic, the founder of the Dominican order. The speaker will turn out to be Saint Bonaventure, a great Franciscan mystic known as the Dottore Serafico. So, following the chiasmic structure already seen in the preceding canto, where the great Dominican Saint Thomas praises Saint Francis and denounces Dominican corruption, here a great Franciscan praises Saint Dominic and then concludes by denouncing Franciscan corruption.

The vita of St. Dominic in Paradiso 12 is a precise rhetorical counterpart to the vita of St. Francis in Paradiso 11. The two eulogies are constructed according to a rigorous system of compensatory rhetoric, as shown in the rhetorical breakdown included below.

The life of St. Dominic, although recounted in less linear and more metaphoric fashion than the life of St. Francis, nonetheless captures his historical importance as a warrior for the church and as a great scholar, who accomplished his studies in record time: “in picciol tempo gran dottor si feo” (Par. 12.85). Picking up the theme of the “insensata cura de’ mortali” — the senseless pursuit of careers like law and medicine and politics — from the beginning of Paradiso 11, Dominic is said to have turned from “the world”, “lo mondo” (82), and from law and medicine (professions exemplified by “Ostiense” and “Taddeo” in Par. 12.83). Motivated not by worldly ambition, but by “his love of the true manna” (Par. 12.84), Saint Dominic becomes a theologian.

So armed, Saint Dominic began the work of overseeing God’s vineyard, a metaphoric reference to the Christian faithful who require constant pruning and ministration in order to thrive:

Non per lo mondo, per cui mo s’affanna di retro ad Ostiense e a Taddeo, ma per amor de la verace manna in picciol tempo gran dottor si feo; tal che si mise a circuir la vigna che tosto imbianca, se ’l vignaio è reo. (Par. 12.82-87)

Not for the world, for which men now travail behind Taddeo or Hostiensis, but through his love of the true manna, he became, in a brief time, so great a teacher that he began to oversee the vineyard that withers when neglected by its keeper.

The supervision and maintenance of God’s vineyard required St. Dominic to use “both his learning and his zeal” — “con dottrina e con volere insieme” (Par. 12.97) — to prosecute the heretics of southern France, in the so-called Albigensian crusade. The Albigensians were the same heretics whom Folquet de Marselha worked to destroy when he was Bishop of Toulouse (see Paradiso 9):

Poi, con dottrina e con volere insieme, con l’officio appostolico si mosse quasi torrente ch’alta vena preme; e ne li sterpi eretici percosse l’impeto suo, più vivamente quivi dove le resistenze eran più grosse. (Par. 12.97-102)

Then he, with both his learning and his zeal, and with his apostolic office, like a torrent hurtled from a mountain source, coursed, and his impetus, with greatest force, struck where the thickets of the heretics offered the most resistance.

We see here how emphatically Dante embraces the Church militant, praising its work in rooting out heresy under the leadership of figures like the Bishop of Toulouse and the founder of the Dominican order.

The balancing and unifying chiasmus that governs Dante’s treatment of the two great mendicant orders is reflected in the very different narrative textures of the two hagiographies. Here is my description of the two divergent narrative approaches from The Undivine Comedy:

The biographies of Francis and Dominic present the methods available to their author declaratively, as well as through their own formal choices. Naive readers, those reading the cantos for the first time who have not yet learned to see the poet’s balancing of structure and rhetoric, experience the two stories as very different, and they usually prefer the story of Francis. In fact, although the two vite are superficially similar, “due archi paralelli e concolori”, in the ways we discussed before, they are — with respect not to structure or imagery but narrative mode — profoundly different. Simply put, Dante tells the life of Francis as a story, adopting an explicitly narrative vein to which readers easily respond; we all love a story. The saint is born, he becomes a youth and falls in love, confronts his father for the sake of his love — it matters not to the seductive narrative line that the lady is called Poverty — attracts disciples, obtains papal approval for his order, preaches in the East, returns to Italy, receives the stigmata, and dies. This is narrative at its most graspable and most pleasurable. By contrast, the infant Dominic in his mother’s womb is the subject of arcane visions and etymological discussions that retard what narrative line there is, and there is very little: although we learn that the saint became a great doctor and fought the heretics, his life is told not by way of a story line proceeding from birth to death but by way of a multitude of similes and metaphors that creates for the reader not the comfortable linearity of canto 11 but rather a pastiche of elusive impressions. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 216)

The large narrative chiasmus that bridges Paradiso 11 and Paradiso 12 requires that St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan, not only praise St. Dominic, but also that he critique the Franciscans.

The coda on the corruption of the current Franciscan order begins in Paradiso 12.106. It is of particular importance because in it Dante engages the controversial history of the Franciscan order, riven since Francis’ death by contending currents, referred to here as those who would “flee” the rule of St. Francis, and those who would “rigidify” it: “ch’uno la fugge, e altro la coarta” (Par. 12.126).

In this dichotomy between those who flee the order and those who rigidify it, we have Dante’s own characterization of the historically debated controversies that led to the splintering of the “Spiritual Franciscans” into a protest movement that was eventually persecuted and condemned. After Francis’s death in 1226, as more and more property began to be amassed by the Franciscan order, a rift formed between the moderates who approved of the accession of property and wealth (known as “Conventuals”) and those who resisted and wanted to preserve the order as Francis had made it (the “Spirituals”).

Dante names representatives of each of the two opposing camps of Franciscans in Paradiso 12.124: on the one hand is Matteo d’Acquasparta, the Minister General of the Franciscan order from 1287 and cardinal from 1288, who steered a moderate course, “fleeing Francis’ rule” in Dante’s phrase (“ch’uno la fugge” in verse 126); and on the other hand is Ubertino da Casale, the Spiritualist, a prolific Franciscan mystic and zealot who, according to Dante, “rigidifies Francis’ rule” (“e altro la coarta” in verse 126).

In the dilemma of fuggire versus coartare Dante neatly captures the problems that erupted after the death of the charismatic leader, Saint Francis, regarding the best way to practice the usus pauperi. The Franciscans were riven by problems of interpretation, divided by the opposing claims of how to read and interpret Francis’s Rule: the “scrittura” of verse 125.

Dante’s “meditation on narrative” in the heaven of the sun (as in the title of chapter 9 of The Undivine Comedy), his focusing on scrittura itself and the complexities of interpretation that perforce accompany any scrittura, thus finds its historical correlative in the controversies surrounding the Rule of the Franciscan order.

We are still wrestling with the complexities of interpreting Dante’s own leanings with respect to the Franciscan order and its controversies. The scholarly community tends to link Dante more to the Spiritualist wing of the Franciscans, given the Commedia’s attacks on avaricious prelates, which begin in Inferno 7, and, even more importantly, his indictment of the Donation of Constantine and the wealth of the Roman Church, a theme that is first deployed in savage fashion in Inferno 19. Nevertheless, it is important to note that in Paradiso 12, Bonaventure condemns equally the two men whom he names: the reformer and leader of the Spiritual wing of the order, Ubertino da Casale, and Matteo di Acquasparta, the cardinal who was associated with the Conventual wing.

Finally, the speaker announces that he is St. Bonaventure:

Io son la vita di Bonaventura da Bagnoregio, che ne’ grandi office sempre pospuosi la sinistra cura. (Par. 12.127-29)

I am the living light of Bonaventure of Bagnorea; in high offices I always put the left-hand interests last.

Bonaventure then introduces the other eleven souls in his circle (the names of the souls who make up the two circles are on the document below). As he goes around the circumference, he comes eventually to the soul next to him, who is the Calabrian prophet Joachim of Flora:

il calavrese abate Giovacchino, di spirito profetico dotato. (Par. 12.140-41)

at my side shines the Calabrian Abbot Joachim, who had the gift of the prophetic spirit.

Joachim is to Bonaventure much as Sigier of Brabant is to Saint Thomas: a more radical and extreme version of himself, with whose positions while alive he emphatically disagreed. Joachim’s mystical and apocalyptic vision of history was championed by some extreme elements of the Franciscan order. Here, in the heaven of wisdom, the two very different men are equidistant from the truth.

Like the previous two canti, Paradiso 12 has been of great interest to historians. There are many names in these canti, and each of these names belongs to a man who played a significant role in intellectual history, political history, and/or religious history. The only exceptions are the two early followers of St. Francis, Illuminato and Augustino, whose lights adorn the second circle and of whom we know next to nothing.

Besides the twenty-four souls who make up the two “crowns” of wise men, there are also the names of Francis and Dominic themselves, as well as many others who participate in the various histories related in these canti: for instance, the two Popes, Innocent III and Honorius III, who gave preliminary and then final approval to Francis’ order in Paradiso 11.92 and 98; the Sultan before whom Francis, an early missionary, preached Christ in Paradiso 11.101-02; and the Franciscans involved in the controversies that overtook the order, creating division and fracture, in Paradiso 12.124.

These names signify here, as they do in Dante’s Limbo (Inferno 4), the dense fabric of the history of ideas woven by Dante in the heaven of the sun.

Return to top

Return to top