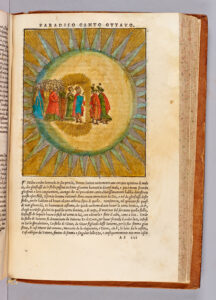

As a prelude to Paradiso 8 and 9, let us note that we are now in the heaven of Venus, named after the classical goddess of love and eros. In some ways Dante’s treatment of this heaven might seem anticlimactic, and certainly I wish that Boccaccio’s Esposizioni alla Comedia di Dante had reached Paradiso 9, so that we might possess the account of Cunizza da Romano’s loves that the great novella writer might have offered us. Dante’s Cunizza refers to her loves, but she talks to us only about politics. Something detailed and embroidered about her amours from Boccaccio, like the fanciful story he tells about Francesca da Rimini in his Esposizioni’s commentary on Inferno 5, would have been delightful. But the absence of a romantic story-line does not signify the absence of love in this heaven.

Indeed, Dante offers a typology of many kinds of human love in this heaven. Let us count the ways:

- eros: “il folle amor” that is featured at the beginning of this canto, in Paradiso 8.2; the irrational and erotic love of the vernacular courtly lyric, originating in Provence; also, as stated here, of classical inspiration;

- classical eros, as in Vergil’s Eclogue 10, “omnia vincit amor, et nos cedamus amori” (love conquers all, and we too yield to love); “la bella Ciprigna” (Par. 8.2), an alternate name for Venus and another alternate, “Dione” (Par. 8.7); see also references to Cupid, Dido, Phyllis, and Hercules as lovers;

- love poets and lovers: Dante (poet of the canzone Voi che ’ntendendo, cited in this canto ), Cunizza da Romano (lover of Sordello), Folchetto (= the Occitan troubadour Folquet de Marselha), Raab (the biblical prostitute Rahab);

- friendship: Dante’s friendship with Carlo Martello, announced by Carlo in Paradiso 8:

Assai m’amasti, e avesti ben onde; che s’io fossi giù stato, io ti mostrava di mio amor più oltre che le fronde. (Par. 8.55-57)

You loved me much and had good cause for that; for had I stayed below, I should have showed you more of my love than the leaves alone.

- marital love: Dante insinuates marital love by the use of the affectionate pronoun “tuo” in “Carlo tuo”, in the apostrophe to Carlo’s wife, ”bella Clemenza”, from the beginning of Paradiso 9:

Da poi che Carlo tuo, bella Clemenza, m’ebbe chiarito, mi narrò li ’nganni che ricever dovea la sua semenza . . . (Par. 9.1-3)

Fair Clemence, after I had been enlightened by your dear Charles, he told me how his seed would be defrauded . . .

- rhetorical copulation: in Paradiso 9 mystical union and co-penentration is expressed in coinages based on pronouns, like inluiare, intuare, inmiare (Par. 9.72 and 81). For the importance of pronouns in Dante’s lexicon of love and unity, see my essay “Amicus eius: Dante and the Semantics of Friendship,” cited in Coordinated Reading.

However, although studded with many references to love of all sorts — beginning with the seductive and promising “folle amore” of Paradiso 8.2 — the heaven of Venus is in fact far more devoted to civic life and politics.

Charles Martel (1271-1294) discusses his family, the French house of Anjou, and refers to his brother, Robert of Anjou, King of Naples (1277-1343), in Paradiso 8.76. This is the very Re Roberto of whose Neapolitan court both Petrarca and Boccaccio make complimentary mention. Petrarch calls King Robert the “only ornament of our age” — “unicum seculi nostri decus” — in Familiarium rerum libri 1.2.9. But in Paradiso 8 Charles, whom we will call Carlo along with Dante, is not complimentary, accusing his brother of miserliness.

The issue of King Robert’s miserliness is of thematic importance, because it is the cue that prompts the key discussion of Paradiso 8. Given that Robert descended from a lineage of generous ancestors, and (as we know from Dante) his brother Carlo is generous, how can the King have turned out to be stingy? This question leads to a lengthy and complex discourse on heredity and human nature. In this discourse Dante makes the case for difference as a prerequisite for a healthy society.

The observation that King Robert’s “natura . . . di larga parca discese” (his nature descended from generous ancestors [Par. 8.82-83]) prompts the question posed in Paradiso 8.93: “Com’esser può, di dolce seme, amaro?” (How can a bitter fruit come from a sweet seed?). Carlo’s reply is another question, but it is rhetorical, intended to lead the pilgrim through dialectical reasoning to an understanding of the need for differentiation:

Ond’elli ancora: «Or di’: sarebbe il peggio per l’omo in terra, se non fosse cive?» «Sì», rispuos’io; «e qui ragion non cheggio». (Par. 8.115-17)

He added: “Tell me, would a man on earth be worse if he were not a citizen?” “Yes,” I replied, “and here I need no proof.”

“Would it be worse for man on earth if he were not a citizen?” is a question that hearkens back to Aristotle, Politics I.1.2: “homo natura civile animal est” (Man is by nature a social animal). From this principle flows the corollary that difference is required in the social sphere as it is in the metaphysical.

We see that the philosophical pendulum of Paradiso has swung from the Augustinian focus of Paradiso 7 back to Aristotle in Paradiso 8.

The question that follows is: can man be a citizen — in other words, can he live a full life as a member of a social group — if there are not different ways of living in society, requiring different talents and duties?

«E puot’elli esser, se giù non si vive diversamente per diversi offici? Non, se ’l maestro vostro ben vi scrive». (Par. 8.118-20)

“Can there be citizens if men below are not diverse, with diverse duties? No, if what your master writes is accurate.”

The answer is that we need difference in the social sphere, and therefore men are born with different dispositions and talents.

Sì venne deducendo infino a quici; poscia conchiuse: «Dunque esser diverse convien di vostri effetti le radici: per ch’un nasce Solone e altro Serse, altro Melchisedèch e altro quello che, volando per l’aere, il figlio perse.» (Par. 8.121-26)

Until this point that shade went on, deducing; then he concluded: "Thus, the roots from which your tasks proceed must needs be different: so, one is born a Solon, one a Xerxes, and one a Melchizedek, and another, he who flew through the air and lost his son.”

One man is born with a disposition for law and governance (Solon), another with the disposition to be a warrior (Xerxes), another has inborn talents that lead him to be a priest (Melchisidech), and, finally, there is one who is born an artist, prone to reckless and daring creativity (Daedalus).

As an aside, let me note that Dante in Paradiso 8.125-26 gives us a second perspective on the myth of Icarus and Daedalus, complementing the vignette of Inferno 17.109-11. There Icarus feels his wax wings unfeathering, and his father Daedalus desperately warns his son “Mala via tieni!” — “You’re going the wrong way!” (Inf. 17.111). In both passages the focus is more on the father than the son, here even more than in Inferno 17. In Paradiso 8 the story is telescoped into the paternal drama of a father who failed to sufficiently protect his son, and consequently lost him: “e altro quello / che, volando per l’aere, il figlio perse” (he who flew through the air and lost his son [Par. 8.125-26]).

Dante’s theme is humans in society: just as we saw that the creation of the universe requires differentiation in Paradiso 2, now we see that the creation of society requires difference as well. The answer to the question about citizenship — “Can there be citizens if men below are not diverse, with diverse duties?” — confirms that the pendulum has swung back.

From stressing the tragedy of our lost similitude with the One in Paradiso 7, Dante has returned to praise of necessary difference in Paradiso 8.

Carlo explains that providence has to correct nature, which if left unguided would turn out children who were exact replicas of their parents. Providence has to intervene to make sure that we are not all identical to our parents:

Natura generata il suo cammino simil farebbe sempre a’ generanti, se non vincesse il proveder divino. (Par. 8.133-35)

Engendered natures would forever take the path of those who had engendered them, did not Divine provision intervene.

Thus Providence corrects nature in order to ensure difference, guaranteeing that we not be like our parents. And yet society is coercive, and tries to force a man to comply with a predetermined idea of what he should be, thus producing terrible results:

Ma voi torcete a la religione tal che fia nato a cignersi la spada, e fate re di tal ch’è da sermone; onde la traccia vostra è fuor di strada. (Par. 8.145-48)

But you twist to religion one whose birth made him more fit to gird a sword, and make a king of one more fit for sermoning, so that the track you take is off the road.

In other words, human beings act against their best interests and against the requirements of a healthy society. God makes sure that we are all different, and yet we try to force our sons into the pathways of their fathers.

Here now is an extended analysis of the discourse summarized above, extending from verse 93 to the canto’s end.

Paradiso 8: Carlo Martello’s Speech

The question is posed in verse 93: “com’esser può, di dolce seme, amaro” (how from a sweet seed, bitter fruit derives)?

This question will be answered thus. The heavens, which impress different characteristics on different human beings, do not distinguish in doing so between one “home” (“ostello” in verse 129) — i.e. one family of birth — and another. As a result, the members of a family can be, indeed are likely to be, completely different. As proof, he cites the example of the biblical twins Jacob and Esau (130-1): twins are as much part of the same family as it is possible to be, since they are born in the same womb, and yet they can be, like Jacob and Esau, completely different.

In effect, Dante is going back to principles about heredity stated in Purgatorio 7 and 8, and before that in his canzone Le dolci rime, where he discusses the nature of nobility and argues that it does not depend on lineage and family. Here he is expanding on the idea that virtue is not passed down through a lineage, as stated in Purgatorio 7.121-3: God does not allow virtue to be passed by blood. Moreover, He impedes this “genetic” transmission deliberately, in order that we humans might know that virtue is given to an individual directly by Him.

The answer to the question posed in verse 93 comes to its conclusion in verse 135 (which marks the conclusion by circling back to the beginning of the discourse with its emphasis on providence: “proveder divino”). What follows, from 136 to the end, is a corollary that explains that what goes wrong happens not because the heavens do their work badly but because of humans, who of their own free will (not stated but always implied) force their family members to go in a direction that does not accord with their natural inclination.

I now offer a more lexically precise breakdown of Carlo’s speech, which brings in many issues before answering the question posed in verse 93. Dante specifically labels this speech an example of deductive reasoning: “Si venne deducendo infine a quivi” in verse 121.

Verse 93: “com’esser può, di dolce seme, amaro” (how from a sweet seed, bitter fruit derives?)

The above question picks up from verses 82-83 about Carlo’s brother, King Robert: ”La sua natura, che di larga para / discese” (His miserly nature is descended from a nature that was generous [Par. 7.82-3])

I. Verses 94-114:

The heavens operate under the guidance of divine providence — note repetition of “provedenza” (99), “le nature provedute” (100), “proveduto fine” (104) — four repetitions that are echoed at the end of the discourse in verse 135: “proveder divino”.

If the heavens were not guided by providence, they would create not order but chaos and ruination (verse 108), and this cannot be (argument per absurdum). This fact, that the heavens operate well but need the guidance of providence in order not to make a mess (“ruine”), will come back in verses 127-35.

II. Verses 115-126:

Introduction of Aristotle on whether man is a “cive”, citizen, and what is required for man to be a citizen in a well-regulated society. In effect, in this passage where Dante invokes Aristotle, he is constructing a syllogism, a form of deductive reasoning that moves from a major premise to a minor premise and hence to a conclusion: to be happy, man must be a citizen; to be a citizen requires different duties; therefore difference is necessary. In conclusion, difference is necessary: men cannot be citizens if they do not live “diversamente per diversi offici” (diversely, with different duties [119]). And “diversi offici” — different offices and duties in society — require different roots, i.e. different origins and births. This is stated in verses 122-3: “Dunque esser diverse / convien di vostri effetti le radici”, to be construed thus: “diverse radici” — different roots — are required, in order to produce “vostri effetti”, namely your [different] effects.

Because this necessary difference is instituted in society by divine providence, we have a Solon, a Xerxes, a Melchesidech, and a Daedalus: all offices are represented, in that we have a governor, a warrior, a priest, and an artist.

III. Verses 127-135

Two key points are made here:

1) verses 127-132: “circular natura” (the heavens), in impressing a particular inclination on “cera mortal” (human wax) does not distinguish between one home and another: “non distingue l’un dall’altro ostello” (129). The heavens do not distinguish between family/lineage. This is why the members of a family can be completely different, like Jacob and Esau, and (the plot premise of this discourse) like Carlo and Roberto.

Let me add that this is also why a person’s birth in a noble family does not guarantee a noble nature. In Dante’s youthful canzone Le dolci rime, he argues (also syllogistically) that noble lineage does not confer nobility.

2) verses 133-135: to achieve this necessary difference (this is the key premise, not stated but carried over from the previous verses), divine providence overrides nature, since left to its own devices the nature that is generated would always reproduce the generator: sons would be like fathers. Which, as has already been shown, providence does not want.

IV. Verses 136-148: Corollary

Here Dante pits natura — what the heavens, with the guidance of providence, have imprinted on each individual mortal — versus fortuna: the social position into which we are born and the pressures caused by that social situation. Nature will always yield poor results if it finds fortuna discordant to it. If we on earth were to pay attention to the “fondamento che natura pone” (143), to the inclination imposed by nature on a given individual, and if we were to follow that inclination (144), then we would have “buona gente” (144), good people: society would have good results, we would flourish.

But instead we, and here we have the implicit presence of free will, with which we freely choose to go in the wrong direction, twist (“torcete”) people against their inclination, making a person who should be a warrior into a priest (forcing a Xerxes to become a Melchesidech), and making a person who should be a priest into a king (forcing a Melchesidech to become a Solon). Therefore we — our society — go off the path!

* * *

I will conclude this commentary by turning to Dante’s canzone Voi che ’ntendendo il terzo ciel movete, cited by Carlo Martello in Paradiso 8.37.

Judging from the dialogue between the pilgrim and Carlo Martello, there was a friendship between them that could only have been kindled during Carlo’s brief visit to Florence in 1294. One of the ways that Carlo shows his intimacy with the pilgrim is by citing Dante’s early canzone Voi che ’ntendendo il terzo ciel movete, written, according to Dante in the Convivio, in 1293. Carlo declares his whereabouts — the third heaven — by citing his friend’s canzone, appropriately addressed to the angelic intelligences of this very third heaven:

Noi ci volgiam coi principi celesti d’un giro e d’un girare e d’una sete, ai quali tu del mondo già dicesti: ‘Voi che 'ntendendo il terzo ciel movete’ . . . (Par. 8.34-37)

One circle and one circling and one thirst are ours as we revolve with the celestial Princes whom, from the world, you once invoked ‘You who, through understanding, move the third heaven’ . . .

One might wonder why Dante would cite here a canzone, Voi che ’ntendendo il terzo ciel movete, in which he turns away from Beatrice to another love. This is a complex question which I first attempted to unravel in the first chapter of Dante’s Poets, dedicated to the Commedia’s autocitations. More recently, I have returned to the problem, which I now frame within the discourse on compulsion and determinism — astral influence — that is so prominent a topic in the early canti of Paradiso.

Return to top

Return to top