- adding a new technique of verisimilitude to his roster, Dante begins Inferno 21 with the tantalizing news that he omits information from his account of Hell, and that there is therefore more to his possible world than he chooses to share: “altro parlando / che la mia comedìa cantar non cura” (talking of things my Comedy is not / concerned to sing [Inf. 21.1-2])

- the rough “tavern humor” and plebeian lexicon adds to the narrative variatio and innovation of lower Hell

- here begins a novella in four acts, with a beffa; it extends from Inferno 21 through the first third of Inferno 23

- a small society comes into focus, with a complex and stratified social order

- this canto offers a major installment in the ongoing Virgilio narrative

- Malacoda’s “truthful lie” vs. Dante’s “lying truth” (the phrases are based on “ver c’ha faccia di menzogna” from Inf. 16.124)

A Novella in Four Acts:

Act 1. Inferno 21, verses 4-57

Act 2. Inferno 21, verses 58-end, and Inferno 22, verses 1-30

Act 3. Inferno 22, verse 31-end;

Act 4. Inferno 23, verses 1-57 Act 4. Inferno 23, verses 1-57

[1] The first tercet of Inferno 21 features the Commedia’s second and last use of the noun — “comedìa” — that gave the poem its title:

Così di ponte in ponte, altro parlando che la mia comedìa cantar non cura, venimmo . . . (Inf. 21.1-3)

We came along from one bridge to another, talking of things my Comedy is not concerned to sing . . .

[2] In this tercet Dante lets us know that, although comedìa tells truth, it does not tell everything: it tells only what has been deemed necessary and important for its readers. Dante here lets us know that he has curated his account of his voyage, having omitted many things that he saw but chooses not to relate.

[3] By claiming to omit some of what he saw, Dante adds to his text’s quotient of realism. He gives life to the text by casually insisting on the life outside the text.

[4] This is one of the many remarkably effective subliminal techniques for garnering verisimilitude of which the Commedia is full. This particular technique, that of putting emphasis on what he is not going to tell us, goes back to Inferno 4, where Dante spells out the power of the poet to withhold information. After the pilgrim joins the bella scola of classical poets and is welcomed as “sixth among such wisdom” (Inf. 4.102), Dante tells us that the group of poets discussed many things, but he does not specify what they were; in fact, he actively omits that information. Rather, he concocts a rather aggressive formula to emphasize the value of such omission, saying that they spoke of matters of which it is as beautiful now to be silent as it was then beautiful to speak: “parlando cose che ’l tacere è bello, / sì com’ era ’l parlar colà dov’ era” (talking of things about which silence here / is just as seemly as our speech was there [Inf. 4.104-5]).

[5] The two travelers have left behind the twisted forms of the diviners in the fourth bolgia. In the second tercet of Inferno 21 they pause at the top of the arched bridge to look down into the next “fessura” — cleft or ditch (4) — which is “mirabilmente oscura” (wonderfully dark [Inf. 21.6]). The reason for the darkness of the fifth bolgia will turn out to be that it is filled with boiling pitch of the sort used to mend ships. All this is explained by way of a famous and detailed comparison between the pitch that is prepared during the winter by the Venetians in their arsenal — “Quale ne l’arzanà de’ Viniziani” (As in the Venetian arsenal [Inf. 21.7]) — and the material prepared in the fifth bolgia, “not by fire, but by the art of God”: “non per foco, ma per divin’ arte” (Inf. 21.16).

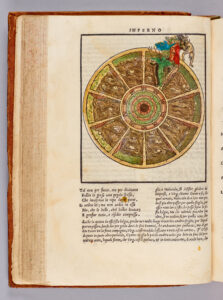

[6] The fifth bolgia of the ten bolge of the circle of fraud holds the barattieri, as specified in Inferno 21.41: “ogn’uom v’è barattier” (there, everyone’s a grafter). Baratteria is a medieval term no longer in use, which signifies fraud committed to obtain illicit gain to the detriment of one’s community; such fraud includes selling influence, taking bribes and kickbacks, and in general corrupting public office and civic life. There is an archaic use of “barratry” in English with a similar, but more localized meaning: fraud or gross negligence of a ship’s master or crew at the expense of its owners or users. For Dante, baratteria is the corruption of the state as simony is the corruption of the Church. Since the term “barratry” is well nigh meaningless in English, I will use the Italian or refer to graft or public corruption.

[7] As a technical and legal matter, baratteria was the crime typically used in Dante’s day as the juridical pretext of those newly come to power for exiling their adversaries. As such it was leveled against Dante and other “Bianchi” (the White party, to which Dante belonged) when the “Neri” (the Blacks) came to power. See Inferno 6 and Inferno 10 for the struggles between the two factions and the ultimate wresting of power from the Bianchi by the Neri, resulting in Dante’s exile. It must have been particularly galling for one such as Dante, deeply committed to the study of ethics and to living an ethical life, to find himself formally accused of baratteria.

[8] Baratteria is the corruption of civic governance, and the result is the corruption of the social order. Hence, in the canti devoted to graft, Dante will create the contours of a small society that is deeply corrupted by mutual and absolute lack of trust.

[9] The treatment of the fifth bolgia is unusually extended (perhaps, some have speculated, because of the autobiographical importance of baratteria as the crime used to justify Dante’s exile). It embraces roughly two and one-third canti: canto 21, canto 22, and the first 57 verses of canto 23. In order to parse the drama’s linear unfolding, I have divided the drama into four narrative blocks or “acts”. If, on the other hand, we consider the narrative materia of this bolgia not as it unfolds in linear time, but structurally, we see that the fifth bolgia boasts two story-arcs, a primary story-arc that extends over the whole bolgia and a secondary story-arc that is inserted into the first:

- Inferno 21.4 – Inferno 23.57: the primary story-arc recounts what happens between Dante and Virgilio and the devils who are the guardians of this bolgia; this story-arc extends all the way from the beginning of Inferno 21 to Inferno 23.57.

- Inferno 22.31 – Inferno 22.151: the secondary story-arc is confined to canto 22 and is the story of what happens between a particular sinner and the devils who capture him; this story-arc begins in Inferno 22.31 and concludes at the end of the canto 22.

[10] We saw this same narrative procedure of a briefer story-arc embedded within a longer one when Dante and Virgilio last encountered devils, at the gates of Dis (Inferno 8-9). There the encounter with Filippo Argenti (Inferno 8) is embedded within the story of the devils’ recalcitrance and unwillingness to open the gate. The opposition of the devils is dealt with by the arrival of the angelic messenger who sweeps everything out of his way.

[11] I will present the events of this bolgia as a “novella in 4 acts” that unfolds over two and one-third canti. The drama involves both sinners and devils; the devils are the guardians of this bolgia, whose job it is to fork the sinners and stick them back under the boiling pitch whenever they try to come up for relief. A devil is described in verses 29-33, where we learn that he is black and fierce, with wings spread wide: “con l’ali aperte e sovra i piè leggero!” (His wings were open and his feet were lithe [Inf. 21.33]).

[12] As the above description of a devil suggests, this is the bolgia that conforms most explicitly to the popular medieval conception of Hell.

[13] Those of you who have read the Decameron can also think of the parallels between the story-line of these canti and the many novelle in which we see the theme of the “beffator beffato”: the trickster who is tricked in turn by someone even cleverer than he. The beffa or deceitful trick is a staple of the novella tradition: in Boccaccio’s hands it is a form of trickery and deceit that has an active and physical component, that is not simply verbal deceit. The beffa will play a major role in this bolgia, particularly in canto 22.

[14] Everyone in this bolgia — including both grafter-prisoners and devil-guards — is tricky and deceitful, and everyone is trying to deceive everyone else. This is Dante’s representation of civic governance.

[15] Military themes and lexicon are featured in Inferno 21 and 22. These themes have the effect of focusing on the state and its citizenry and the weighty responsibilities of those who govern, the very responsibilities that are abused by the grafters. The simile of the Venetian arsenal at the beginning of Inferno 21 emphasizes civic industry and collaboration. Likewise, the autobiographical reference to the battle of Caprona in Inferno 21.95 serves to remind us of Dante’s own civic engagement: as a citizen of Florence he was also perforce a member of the militia and had the responsibility to take part in battle, a responsibility that he fulfilled.

Act 1. Inferno 21, verses 4-57

[16] After the introductory sequence describing the features of the fifth bolgia, Dante begins the action with the arrival of a devil. The first devil calls out to his fellow devils, “O Malebranche” (37), thus giving us for the first time an appellation for the diabolic denizens of this realm. We are in a place that, as we learned in Inferno 18, is “detto Malebolge” (called Malebolge [Inf. 18.1]); we recall that Malebolge means “evil sacks” or “evil ditches”. We now learn that the diabolic guradians of this evil ditch are the “Malebranche” (Inf. 21.37) or “evil claws”; we will learn further on that their leader is named “Malacoda” (Inf. 21.76) or “evil tail”. The society of devils who inhabit the fifth bolgia is coming into focus.

[17] The first unidentified devil carries an “anziano” (Inf. 21.38): a magistrate, holder of public office, the equivalent of prior in Florence. Through the reference to the local cult of “Santa Zita” (Inf. 21.38) it is stipulated that this magistrate is from Lucca. The focus on Lucca, a Tuscan city, highlights the theme of civic graft as part of the urban fabric in city-states like Lucca and Florence.

[18] As I mentioned above, this bolgia conforms to the popular conception of Hell. Along with its popular infernal iconography of devils armed with prongs and hooks, it also features popular diction and humor. Carrying the sinners by the ankles, slung over their shoulders in the way that butchers carry carcasses (34-36), the devils are compared to cooks who order their scullery-urchins to force the meat in the pot back down under the broth, so that it does not float:

Non altrimenti i cuoci a’ lor vassalli fanno attuffare in mezzo la caldai la carne con li uncin, perché non galli. (Inf. 21.55-57)

The demons did the same as any cook who has his urchins force the meat with hooks deep down into the pot, that it not float.

[19] In the precision of “cuoci” and their “vassalli” we see an emblem of the stratified social order that emerges from these canti. If we begin to form in our minds the image of a huge kitchen in a castle, populated by cooks and scullery-urchins and enormous pots of boiling broth, that image will be in keeping with the sinner whom we meet in the next canto. The action of Inferno 22 revolves around an unnamed petty embezzler who lived on the seedy fringes of life in the castle of King Thibaut II of Navarre.

[20] Dante will come back to this image of meat floating in a pot of boiling broth at the end of Inferno 21, where the sinners are called “li lessi dolenti” (the sorrowful boiled ones [Inf. 21.135]). The adjective lesso conjures boiled meat, as in the current usage “carne lessa” or meat that has been cooked in boiling water.

Act 2. Inferno 21, verses 58-end, and Inferno 22, verses 1-30

[21] Now begin the interactions and negotiations between Dante, Virgilio, and a troop of devils bearing evocative names and led by Malacoda. For the first time in their journey together Virgilio orders Dante to hide. At the same time that Virgilio demonstrates concern, he also attempts to be reassuring. He tells his charge not to fear, for he knows how to handle devils, having dealt with them on a previous occasion:

e per nulla offension che mi sia fatta, non temer tu, ch’i’ ho le cose conte, perch’ altra volta fui a tal baratta. (Inf. 21.61-63)

No matter what offense they offer me, don’t be afraid; I know how these things go— I’ve had to face such fracases before.

[22] Virgilio’s reminder that he has been here before, intended to reassure, is not very reassuring when we consider the two possible referents for “altra volta” in verse 63. The phrase refers to the “other”, or previous, occasion on which Virgilio was faced with such a fracas. The “altra volta” can refer to the time, long before this journey, when Virgilio went to the pit of Hell conjured by the sorceress Erichtho (see Inferno 9), or it can refer to the time, within the parameters of this journey, when he attempted to negotiate with the devils at the gate of Dis (see Inferno 8 and 9). The first occasion is tainted because of its association with black magic and coercion by the forces of evil. The second occasion too is less than reassuring because Virgilio’s negotiations with the devils at the gate of Dis did not result in success.

[23] We know that the pilgrim will not find a reminder of the events at the gate of Dis reassuring because he has already stated clearly, to Virgilio, that he knows his guide failed on that occasion. In Inferno 14 the pilgrim tellingly addresses his guide as “you who can defeat / all things except for those tenacious demons / who tried to block us at the entryway”:

Maestro, tu che vinci tutte le cose, fuor che ’ demon duri ch’a l’intrar de la porta incontra uscinci (Inf. 14.43-45)

[24] Despite his previous failure, and despite the pilgrim’s obvious awareness of that failure, Virgilio remains touchingly confident in his abilities. And yet he is facing a greater challenge than the one he faced in Inferno 8-9.

[25] At the gate of Dis Virgilio negotiates with devils who remain anonymous. They are truculent and defiant. They sing in only one key: that of resistance and opposition. Effectively, what they communicate is: “no, you may not pass, we are committed to blocking your passage”.

[26] Malacoda, an individualized devil with a name and personality, has many more arrows in his quiver. Instead of being overtly truculent and overtly defiant, he is suavely charming and apparently helpful. In other words, Malacoda is a master of deceit.

[27] With the addition of much more color and detail, and with a baroque and burlesque unfolding of diabolic names that correspond to varying diabolic personalities — Malacoda, Alichino, Calcabrina, Cagnazzo, Barbariccia, Libicocco, Draghignazzo, Ciriatto, Graffiacane, Farfarello, Rubicante —, the scene from Inferno 8 is now reprised and modulated, replayed not in the key of defiance but in the key of malice and deceit.

[28] Virgilio explains to Malacoda that his mission as guide to someone — an unspecified someone, for Dante is still in hiding — through the infernal regions is willed by God. Malacoda replies with a resignation that is likely feigned but that immediately results in Virgilio summoning Dante from his hiding place. The suggestion is that Virgilio is too trusting in the power of reason.

[29] The narrator compares the fear that he feels on coming forth from hiding to the fear of the conquered Pisan soldiers whom he personally saw exit the castle of Caprona after the battle of August 1289. A pact was struck at Caprona, whereby the Pisans, having surrendered, would be allowed to exit the castle with guarantee of safe-passage. Similarly, a pact has been struck here, in the fith bolgia, between Virgilio and Malacoda. But Dante-pilgrim fears that the pact cannot be trusted, and of course he is right.

[30] Throughout this drawn-out encounter with devils, the pilgrim is not as trusting as his guide. The pilgrim resists Malacoda’s offer of an escort and continues to consider the devils hostile in verses 127-32. Virgilio is wrong when he states categorically toward the canto’s end (verses 133-5) that Dante has nothing to fear. Reasonable Virgilio is deceived by Malacoda’s reasonable demeanor.

[31] Malacoda weaves truth with falsehood into a perfectly designed trap, giving instructions and information that seem straightforward and helpful to Virgilio but that his troops can decode as deceitful and hostile. We can parse Malacoda’s speech, labeling its sections true or false. In this way we can see how cleverly the devil weaves falsehoods with truths to create a fabric of deceit:

- Verses 106-8: “Più oltre andar per questo / iscoglio non si può, però che giace / tutto spezzato al fondo l’arco sesto” (You can go no farther / on this ridge, because the sixth bridge / lies smashed to bits at the bottom there) TRUE

- Verses 109-11: “E se l’andare avante pur vi piace, / andatevene su per questa grotta; / presso è un altro scoglio che via face” (Yet if you two still want to go ahead, / move up and walk along this rocky edge; / nearby, another ridge will form a path) FALSE

- Verses 112-14: “Ier, più oltre cinqu’ ore che quest’otta, / mille dugento con sessanta sei / anni compié che qui la via fu rotta” (Five hours from this hour yesterday, / one thousand and two hundred sixty-six / years passed since that roadway was shattered here) TRUE

[32] More succinctly, Malacoda’s three declarations can be labeled thus:

- It is TRUE that the way forward is obstructed because the sixth bridge lies smashed to bits on the floor of Hell.

- It is FALSE that they will eventually find an unbroken bridge over the bolgia.

- It is TRUE that the shattering of the bridge occurred precisely 1266 years ago (plus one day minus five hours).

[33] The falsehood of an intact bridge that the travelers will access further on is successfully packaged as truth, by being sandwiched between the truthful statements on either side of it.

[34] In verses 115-26 Malacoda orders his troop to set out on a reconnaissance mission; they are to check on sinners who have exited the pitch and simultaneously to accompany the travelers to the next bridge. He concludes with a clear signal that the travelers are fair game, for they are to be kept safe until they arrive at the next intact crossing-point: “costor sian salvi infino a l’altro scheggio / che tutto intero va sovra le tane” (keep these two safe and sound till the next ridge / that rises without break across the dens [Inf. 21.125-26]).

[35] However, there is no bridge that crosses over the next bolgia intact — “tutto intero” (all whole [Inf. 21.126]) — since all the bridges over the sixth bolgia were shattered at the same time. Hence Malacoda’s instruction to his fellow-devils to guide Dante and Virgilio and to keep them safe until (“infino a”) they reach the next intact bridge is a covert instruction to attack them. Malacoda’s safe-passage is a fraud.

[36] Malacoda correctly informs the travelers that the broken bridge was shattered 1266 years ago (plus one day minus five hours), in other words, he correctly informs them that the bridge fell during the earthquake that accompanied Christ’s Crucifixion. However, he omits the information that at that time all the bridges over the sixth bolgia crumbled and fell in ruins to the floor of Hell. There is thus no intact bridge over the sixth bolgia.

[37] The devil embeds his lie about the bridges over the sixth bolgia of Malebolge into his truthful account of the earthquake that accompanied the Crucifixion. The larger truth to which he attaches his falsehood makes his lie compelling and assures the success of his deceit. Malacoda’s account is so truthful, so “historical,” that he dates Dante’s journey by telling us the precise number of years that have passed since Christ harrowed Hell and so caused the infernal “ruine” to be formed (for the ruine, see Inferno 12):

Ier, più oltre cinqu’ore che quest’otta, mille dugento con sessanta sei anni compié che qui la via fu rotta. (Inf. 21.112-114)

Five hours from this hour yesterday, one thousand and two hundred sixty-six years passed since that roadway was shattered here.

[38] The earthquake occurred in the year 34 CE at noon of Good Friday. It is now 1266 years plus one day minus 5 hours later: in other words, it is now 7 AM of Holy Saturday in the year 1300. In order to deceive Virgilio and Dante, Malacoda offers true and precise information with which we can date the pilgrim’s journey. Indeed, Malacoda’s reference is so important that all our critical discussions as to precise dates and times within the Divine Comedy begin from the information that Malacoda provides us in Inferno 21.

[39] Malacoda dates Dante’s journey. He does so by stipulating the precise amount of time that has elapsed — in years, days, and even hours — since the Crucifixion.

[40] Malacoda is able to deceive Virgilio because he accompanies his lie with a great truth: the date of the death of Christ. Moreover, Dante fashions a backstory that is chronologically very subtle and precise. Malacoda is able to deceive Virgilio about the state of the bridges over this bolgia because the Roman poet does not know that the bridges have fallen: when he was previously here, the bridges were still intact. In other words, Virgilio’s first trip to lower Hell antedates the earthquake caused by Christ’s Harrowing of Hell; it antedates the earthquake that caused these bridges to crumble and the other ruine to form. Virgilio indeed tells us as much in Inferno 12. With respect to the ruina that marks the entrance to the seventh circle, Virgilio informs the pilgrim that the great landslide was not present when he journeyed this way before: “Or vo’ che sappi che l’altra fïata / ch’i’ discesi qua giù nel basso inferno, / questa roccia non era ancor cascata” [Now I would have you know: the other time / that I descended into lower Hell, / this mass of boulders had not yet collapsed [Inf. 12.34-6]).

[41] Let us reconstruct the chronology. We have just learned from Malacoda that the bridges over the sixth bolgia fell as a result of the Harrowing of Hell. In Inferno 9, Virgilio tells Dante that he was newly stripped of his flesh — newly dead — when Erichtho summoned him: “Di poco era di me la carne nuda” (My flesh had not been long stripped off [Inf. 9.25]). Therefore, Erichtho caused Virgilio to journey to lower Hell in the window of 54 years that transpired between the Latin poet’s death in 19 BCE and Christ’s arrival in Limbo in 34 CE. The fashioning of so precise a backstory adds psychological density and realism to Dante’s Virgilio-narrative.

[42] Malacoda’s truthful lie — in effect, a falsehood that appears true — is the precise inverse of comedìa, a truth that appears false. When Dante first uses the term comedìa in the context of Geryon’s arrival in the final verses of Inferno 16, he defines it as a “truth that has the face of a lie”: “ver c’ha faccia di menzogna” (Inf. 16.124). In other words, Dante defines comedìa as a truth that may at times appear false: “a comedia is that truth which has the appearance of a lie but which is nonetheless always a truth” (Dante’s Poets, p. 214).

[43] Inferno 21 ends with a burlesque treatment of military behavior as practiced by devils in Hell and with a famous instance of the low “tavern humor” that characterizes this bolgia. The devils signal to their leader that they have understood his instructions by pressing their tongues between their teeth. He in turn signals them to depart on their mission with a trumpet blast from his ass:

ma prima avea ciascun la lingua stretta coi denti, verso lor duca, per cenno; ed elli avea del cul fatto trombetta. (Inf. 21.137-39)

But first each pressed his tongue between his teeth as signal for their leader. And he had made a trumpet of his ass.

[44] A comedìa necessarily embraces and meditates on all forms of semiosis, because it embraces and meditates on all forms of reality.

Return to top

Return to top