- Dante’s personal and anomalous re-conceptualization of Limbo: Dante’s idea of including virtuous pagans in this space is radical, making his Limbo different from all others in the history of this religious idea

- In the Commedia Dante creates two categories of virtuous pagans, focusing more attention on the first:

- those who are excluded from the Christian dispensation temporally, being born before the birth of Christ;

- those who are excluded from the Christian dispensation geographically, being born after the birth of Christ, but in non-Christian lands

- Limbo as Dante conceives it houses not only the traditional unbaptized children but also virtuous pagans of classical antiquity who lived before Christianity: these pagans include great poets (e.g., Homer, Vergil, Horace, Ovid, Lucan) and philosophers (e.g., Aristotle, Socrates, Plato)

- Dante’s Limbo also houses a few contemporary virtuous non-Christians, notably three Muslims: a general and Sultan of Egypt, Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn), and two philosophers, Avicenna (Ibn-Sīnā) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd)

- The issue of virtuous non-Christians involves Dante’s guide Virgilio and will be complicated by the presence in the Commedia of saved pagans, starting with Cato of Utica in Purgatorio 1 and culminating with Ripheus the Trojan in Paradiso 20

- The issue of exclusion with its enormous consequences leads directly to Dante’s investment in cultural transmission: textual and oral transmission carries ideas across cultural boundaries and allows access to Christian teachings

- The document “The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized”, published by the International Theological Commission in January 2007, effectively constitutes a second Harrowing of Hell — this time releasing unbaptized children from Limbo

- Appendix on the historiography of Limbo

[1] Inferno 4 treats the first circle of Dante’s Hell, dedicated to the space that theologians call “Limbo”. As I will explain in this commentary, Dante’s treatment of Limbo is anomalous within the history of this idea. Dante’s way of conceiving Limbo is personal and original: it is a radical re-conceptualization, different from all others in the history of the idea of Limbo. On this issue, see my essay “Dante’s Limbo and Equity of Access: Non-Christians, Children, and Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion, from Inferno 4 to Paradiso 32”, listed in Coordinated Reading; the historiographic analysis from my essay is excerpted in the Appendix below.

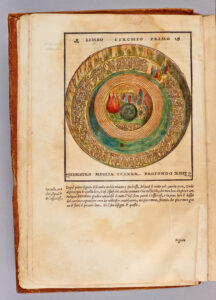

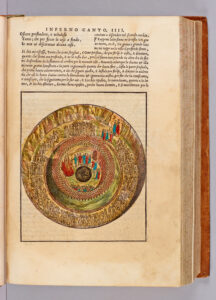

[2] The word Limbo means “edge” or “hem”, as in the hem of an article of clothing. Limbo was imagined by theologians to be a privileged zone on the very margin of Hell where the only punishment is deprivation. These souls are deprived of God and of heaven. These souls are deprived of God and of heaven, but are spared physical torment, experiencing “duol senza martìri” (sorrow without torment [Inf. 4.28]).

[3] Limbo was imagined as palliative and consolatory; within the Catholic imaginary, to be placed in Limbo is to be granted favored status. Essentially, the idea of Limbo reveals the cultural punctum dolens that requires consolation: for Catholics throughout history the thought of unmitigated damnation for unbaptized babies has required the consolation offered by Limbo. Dante pushes the concept of Limbo in an unprecedented direction, proposing it as a space for the mitigation of damnation for virtuous non-Christians.

[4] Dante stands alone in the history of the idea of Limbo in opening this palliative space to virtuous non-Christians, to adults of non-Christian faiths. We cannot overstate what this move tells us about the boldness of his cultural and moral imagination.

[5] Because there is never any physical torment in Limbo, as traditionally conceived, and because Dante in particular emphasizes the special status of the souls whom he places in his non-traditional Limbo, some commentators and readers of Inferno 4 over the years have resisted the idea that Limbo is the first circle of Dante’s Hell. However, Dante is explicit on this score, telling us that we have entered “nel primo cerchio che l’abisso cigne” (in the first circle girding the abyss [Inf. 4.24]).

[6] Dante in fact exploits the tension between the special status that he accords the souls of his Limbo and the reality that this is the first circle of his Hell. As I write in The Undivine Comedy:

Locating it with numerical precision, Dante has distinguished Limbo in a way that seems straightforward, clear, and not susceptible to confusion: it is the first circle of Hell. And yet, master of the manipulation of narrative — i.e., textual time — to create dialectical perspectives, Dante will dedicate the rest of canto 4 to making us disbelieve this simple fact, and indeed, how many readers “forget” that Limbo is Hell’s first circle! (The Undivine Comedy, p. 37)

[7] The Catholic religion posited a limbus patrum (“Limbo of the fathers”), the temporary condition of Old Testament saints as they awaited their liberation by Christ, and the limbus infantum or limbus puerorum (“Limbo of infants” or “Limbo of children”), the permanent condition of infants and children who died prior to baptism, hence not washed of original sin. Traditionally, therefore, theologians placed two groups of souls in Limbo, the Biblical righteous of the Old Testament and infants who die unbaptized.

[8] The Biblical righteous were liberated from Limbo by Christ when he harrowed Hell, according to Dante in 34 CE (this is the date for the Harrowing of Hell that Dante supplies in Inferno 21). Therefore, by the time of Dante’s journey in 1300 CE, the Hebrew patriarchs and matriarchs were long removed from Hell and lodged in Paradise. In fact, in 1300, a theologically orthodox Limbo should house only unbaptized infants. After the removal of the Biblical righteous, there should be no adults whatsoever.

[9] Dante’s divergence from orthodoxy is immediately signalled by the description of the crowds of souls gathered in Limbo, composed “of infants and of women and of men”: “d’infanti e di femmine e di viri” (Inf. 4.30). Of the three groups of souls here specified, only infants belong in a theologically correct Limbo. The presence of adults here indicates that Dante has gone in a different and idiosyncratic direction.

[10] Who are these adults in Dante’s Limbo? They are the souls of great non-Christians who lived lives of extreme moral virtue and intellectual accomplishment. Dante’s idiosyncratic handling of Limbo, his deviation from theological orthodoxy, thus becomes an index with which we can measure his passionate reverence for towering humanistic achievement, irrespective of the faith from which such achievement springs.

[11] In Virgilio’s explanation, these are the souls of those who committed no personal sin of their own but who were not baptized, hence not released from original sin, the “umana colpa” (human sin) of Purgatorio 7.33. Virgilio is very clear that the souls in Limbo did not sin: “ch’ei non peccaro; e s’elli hanno mercedi, / non basta, perché non ebber battesmo” (they did not sin; and yet, though they have merits, / that’s not enough, because they lacked baptism [Inf. 4.34-5]). According to this account, the failure of these souls to worship Christ is due simply and only to their having lived prior to Christ’s birth: “dinanzi al cristianesmo” (before Christianity [Inf. 4.37]).

[12] Virgilio tells Dante that he himself belongs to this group of pagans who lived “dinanzi al cristianesmo” — “e di questi cotai son io medesmo” (and of such spirits I myself am one [Inf. 4.39]) — and restates categorically that the only “defects” of the souls of Limbo are the ones named above: “Per tai difetti, non per altro rio, / semo perduti” (For these defects, and for no other evil, / we now are lost [Inf. 4.40-1]). Their “defects” are thus that they were not baptized and that they failed to worship Christ. Their failure, according to this narrative, occurred through no fault of their own, but because of the unfortunate timing of their birth.

* * *

[13] Having reconfigured Limbo as a space that houses virtuous non-Christians, Dante now alters the landscape of Hell as a further means of indicating the special status of these souls.

[14] At the beginning of Inferno 4, he had already stipulated the darkness of the abyss: “Oscura e profonda era e nebulosa” (dark and deep and filled with mist [Inf. 4.10]). Now he designates for the first circle of Hell a light that conquers the darkness: “io vidi un foco / ch’emisperio di tenebre vincia” (I beheld a fire / that carved out a hemisphere from the shadows [Inf. 4.68-9]). This fire is the only light in Hell. Moving towards this light, he finds a “nobile castello” (noble castle [Inf. 4.106]), surrounded by a “bel fiumicello” (beautiful little river [Inf. 4.108]), and a “prato di fresca verdura“ (fresh green meadow [Inf. 4.111]). Here the honorable souls — the poets, philosophers, and heroes — are assembled: “in loco aperto, luminoso e alto, / sì che veder si potien tutti quanti” (an open place both high and filled with light, / so we could see all those who were assembled [Inf. 4.116-17]).

[15] The pilgrim poses a query based on his perception that these souls are treated differently from other souls: ‘‘questi chi son c’hanno cotanta onranza, / che dal modo de li altri li diparte’’ (who are these souls whose dignity has kept / their way of being, separate from the rest? [Inf. 4.74-5]). The remarkable answer is that the honor these souls accrued while alive was such as to win them grace from heaven:

E quelli a me: “L’onrata nominanza, che di lor suona sù ne la tua vita, grazia acquista in ciel che sì li avanza”. (Inf. 4.76-8)

And he to me: “The honor of their name which echoes up above within your life, gains Heaven’s grace, and that advances them”.

[16] We note the word “nominanza”, derived from “nome” (name). While the names of the cowardly souls in the previous canto are erased from memory, the names of the virtuous pagans live on, winning them glory on earth and even, says Dante — displaying his humanistic values — a special status in Hell.

[17] The names of the virtuous pagans live on, because texts record them. Therefore, if the lists of names in Inferno 4 seem somewhat tedious to read, we can literally “enliven” them. We need only consider that these names are the talismans of well-lived lives that are also well recorded in books: each name summons much cultural history and cultural memory, for which the name stands as a synecdoche.

[18] We remember that the “catalogue of ships” is an epic trope from the Iliad (a trope that Dante knew from the Aeneid’s catalogues, modeled on Homer’s), and that for Homer, as for Vergil and for Dante, the lists of names testify to the responsibility of the epic poet to preserve a society and a culture. Names thwart time and defy oblivion. Dante himself, who will be embraced by the great poets of antiquity as one of their group, “the sixth among such intellects” — “sesto tra cotanto senno” (Inf. 4.102) — will carry out this epic mission through the Florentine and Italian names recorded in the Commedia, most explicitly in “the Florentine phonebook” of Paradiso 16.

[19] The word “nominanza” is important to Dante, as we will confirm in Purgatorio 11. It hearkens back always to its first use here in Inferno 4, and thus to the deserved fame and special worth of the virtuous non-Christians whose names are recorded here. Moreover, the lists of names, which include both historical and literary figures, are fascinating in their multiculturalism. There are names of Hebrews, Romans, Greeks, Egyptians, and Muslims. The Hebrews are: Adam, Abel, Noah, Moses, Abraham, David, Jacob, Isaac, Jacob’s sons, Rachel. The Greeks are: Homer, Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Democritus, Diogenes, Anaxagoras, Thales, Empedocles, Heraclitus, Zeno, Dioscorides, Euclid, Hippocrates, Galen. The Romans are: Vergil, Horace, Ovid, Lucan, Aeneas, Caesar, Latinus, Lavinia, Brutus, Lucretia, Julia, Marcia, Cornelia, Cicero, Seneca. The Egyptians are: Ptolemy, Saladin. The Muslims are: Avicenna, Averroes, Saladin.

[20] Not only does Dante reverence what the men and women of Inferno 4 accomplished while alive, he believes them to be perfectly good, sinful only in their culturally-induced failure to believe. Dante’s extreme awareness of the cultural barriers to belief in Christ is articulated in the heaven of justice, where the pilgrim asks how it can be just to exclude from heaven a perfectly just man who happens to be born on the banks of the river Indus:

ché tu dicevi: “Un uom nasce a la riva de l’Indo, e quivi non è chi ragioni di Cristo né chi legga né chi scriva; e tutti suoi voleri e atti buoni sono, quanto ragione umana vede, sanza peccato in vita o in sermoni. Muore non battezzato e sanza fede: ov’è questa giustizia che ’l condanna? ov’è la colpa sua, se ei non crede?” (Par. 19.70-78)

For you would say: “A man is born along the shoreline of the Indus River; none is there to speak or teach or write of Christ. And he, as far as human reason sees, in all he seeks and all he does is good: there is no sin within his life or speech. And that man dies unbaptized, without faith. Where is this justice then that would condemn him? Where is his sin if he does not believe?”

[21] The souls whom Dante places in Limbo pose a challenge to justice similar to that of the “man born on the banks of the Indus” of Paradiso 19. How can it be just, the poet wonders in Paradiso 19, to condemn a person who lived with perfect virtue, just because the circumstances of his birth denied him the knowledge of Christianity? The language that describes the man born on the banks of the Indus — “there is no sin within his life or speech” ((Par. 19.73) — can be transposed to Virgilio, and the language that describes the virtuous non-Christians of Inferno 4 —“they did not sin” (Inf. 4.34) — can be transposed to the man born on the banks of the Indus.

[22] The overlap occurs because Dante creates two categories of virtuous exclusion in the Commedia: 1) the first category contains those who are excluded from the Christian dispensation temporally, being born before the birth of Christ; 2) the second category contains those who are excluded geographically, being born after the birth of Christ, but in non-Christian lands. The first category leads to the remarkable invention of Dante’s Limbo, and the second category yields the remarkable critique of the justice that could exclude from salvation the contemporary man born on the banks of the Indus, who has no access to knowledge of Christ.

[23] Here we encounter Dante’s great sensitivity to the issue of exclusion and its inequity, connected to the cognate issue of access to knowledge and thus to cultural and textual transmission. The virtuous man of Paradiso 19 lives in a place where there is “no one to speak or teach or write of Christ” (Par. 19.71-2). He requires knowledge of Christ, orally or textually transmitted, in order to be saved, but such knowledge is not available, adding to the injustice of his damnation. In the same vein, in Purgatorio 22 Statius explains that he was saved because of the knowledge of Christ that he received from the texts of the Gospels and (with terrible irony) from the texts of his revered Vergil. As the testimony of Statius in Purgatorio 22 and the case of the man born on the banks of the Indus of Paradiso 19 testify, knowledge is necessary for salvation.

[24] Dante had poignantly analyzed the importance of one’s place of birth already in the Convivio, where he considers the disadvantages that accrue to someone who has no access to a University or to educated people: “L’altra è lo difetto del luogo dove la persona è nata e nutrita, che tal ora sarà da ogni studio non solamente privato, ma da gente studiosa lontano” (The other is the handicap that derives from the place where a person is born and bred, which at times will not only lack a university but be far removed from the company of educated persons [Conv. 1.1.4]). He had the advantage of being born in Florence. Dante’s keen awareness of the structural importance of equity of access to knowledge informs all his thinking on virtuous non-Christians.

Appendix

Giorgio Padoan (1969) and Chiara Franceschini (2017) on Limbo

Excerpt from:

Teodolinda Barolini, “Dante’s Limbo and Equity of Access: Non-Christians, Children, and Criteria of Inclusion and Exclusion, from Inferno 4 to Paradiso 32” (in Dante’s Multitudes: History, Philosophy, Method [South Bend: Notre Dame UP], 2022, pp. 58-81)

In 1969, Giorgio Padoan published “Il Limbo dantesco,” a groundbreaking essay that affirms and documents the radical tenor of Dante’s Limbo. Padoan points to Dante’s inclusion of adults in his Limbo, the virtuous pagans of antiquity and even some contemporary Muslims, as a massive deviation from the contemporary theology of Limbo. He points also to the failure of Dante scholarship to evaluate the significance of Dante’s deviation, although Dante’s deviation amounts to an unparalleled intervention into the history of this particular theological idea. Padoan is explicit about the remarkable anomaly of including adults in Limbo, claiming, correctly, that Dante “si oppone drasticamente a tutta la tradizione teologica del suo tempo (ed anche successiva) dichiarando che nel Limbo si trovano non solo bimbi morti in tenerissima età ma anche adulti” (Dante drastically opposes the entire theological tradition of his time, and the successive tradition as well, when he declares that Limbo holds not only babies who died as infants but also adults).[i] Very important here, and prophetic with respect to recent changes in church doctrine on Limbo, is Padoan’s note that only in the twentieth century were adults added to Limbo, referring explicitly to those who are intellectually or culturally disabled: “Solo agli inizi del nostro secolo la teologia cattolica ha ammesso che nel Limbo accanto ai bimbi possano essere anche degli adulti: ma in tal caso si tratterebbe di persone intellettualmente ritardate, o dell’età preistorica o di tribù primitive, e simili” (Only at the beginning of our century did Catholic theology admit that next to the infants there could also be adults: but in this case they were people who were intellectually retarded, or from prehistoric times or primitive tribes, or the like).[ii]

With respect to the state of Dante scholarship on Limbo, Padoan notes that, instead of historicizing and thereby measuring Dante’s deviations from the theology of Limbo, “modern commentaries” (by which he means commentaries written before the time of his writing, in the late 1960s) minimize the differences between the poet and the theological tradition:

I commenti moderni hanno sottolineato, giustamente, soprattutto la viva ammirazione che Dante qui esterna con ogni evidenza per il mondo antico, anzi per le virtù intellettuali, civili e morali dell’uomo; ma, tranne qualche rapido cenno, peraltro non posto risolutamente al centro del discorso e quindi non sviluppato conseguentemente, non hanno affrontato il problema sul versante strettamente teologico; e quelli che più, per i loro interessi ideologici, avrebbero dovuto sentirsi impegnati a misurare precisamente il divario che distacca qui l’Alighieri dalle concezioni teologiche correnti nel suo tempo si sono invece sentiti in dovere, cedendo forse a sollecitazioni agiografiche, di minimizzare le diversità tentando di ricondurre il poeta entro i binari bonaventuriani e tomisti: come se tacere o minimizzare o addirittura falsare i termini di un problema, qual che esso sia, serva a qualcosa.[iii]

[Modern commentaries have underlined, correctly, the strong admiration for antiquity that Dante here makes manifest, especially for its intellectual, civic, and moral virtues. However, but for an occasional remark, not central or developed, these critics did not confront the issue from a strictly theological perspective; and those critics who could best have engaged in measuring with precision the distance that here separates Dante from contemporary theological belief instead felt obligated, perhaps yielding to the solicitations of hagiography, to minimize those differences. They tried to situate Dante within Bonaventurian and Thomistic paradigms, as though it could be useful to silence, minimize, or indeed to falsify the terms of the debate.]

Padoan’s 1969 essay does the work of measuring the distance that separates Dante from theological orthodoxy with respect to Limbo. His rigorous and creative scholarship offered me, as a graduate student in the 1970s, my first insight into the immense gains of historicizing in the field of Dante studies: in this case, the gains of historicizing the idea of Limbo. By historicizing Limbo, Padoan opens our eyes to the radical nature of Dante’s thought; he was the first critic to show me that Dante is capable of — even sometimes inclined to — radical thought. Padoan does not exaggerate when he writes, in the conclusion of “Il Limbo dantesco,” that Dante’s treatment of Limbo constitutes a conscious violation of theological thought: “è una violazione consapevole e risoluta di quanto al proposito aveva elaborato l’investigazione teologica” (it is a conscious and resolute violation of what had been proposed by theological investigation).[iv]

However, scholarly commentaries that accumulate over many centuries are slow to progress, and Padoan’s masterful historical contextualization of Dante’s Limbo has still to be fully integrated into the reception of Inferno 4. Most unfortunately, the recent Storia del limbo of 2017 by Chiara Franceschini does not register the existence of Padoan’s essay.[v] A comprehensive study of this sort, more than two-thirds of it devoted to the post-medieval period, cannot of course be expected to master every individual bibliography. But Dante’s Limbo is, literally, an exceptional case, and therefore a better understanding of the historiography with respect to Dante is essential. The author’s treatment of the ancient commentators is more useful and balanced than her treatment of contemporary historiography, although with respect to the ancients too we would profit from a greater ability to contextualize a given commentator: for instance, Boccaccio is consistently more squeamish about any sign of heterodoxy than, say, Benvenuto da Imola. In fact, Boccaccio’s sensitivity to church doctrine leads him to be particularly acute on Inferno 4 and therefore to figure prominently in this essay.[vi] Franceschini’s treatment of modern scholarship on Dante’s Limbo is scattershot. She both dignifies hypotheses that have not achieved any critical traction — for instance, Montanelli’s hypothesis that Dante moves away from the radical nature of his Limbo over the course of the three cantiche — and ignores fundamental contributions like Padoan’s. And, at the end of her analysis, Franceschini arrives at perplexity: a perplexity based on an unwillingness to countenance Dante’s exceptionalism.

Perhaps because of a methodology founded on demonstrating iron-clad transmission, Franceschini finds it difficult to accept that Dante invented the idea of putting adult virtuous pagans in Limbo. Her chapter 3, “Dante e il limbo dei pagani,” thus devotes itself to searching for the missing precursor. While she critiques Dante scholars for referring to “una supposta ‘norma,’ una cosiddetta ‘dottrina tradizionale’” (a supposed “norm,” a so-called “traditional doctrine”), Franceschini herself confirms the existence of just such a doctrine and such a norm and is stymied by Dante’s anomalous deviation from it.[vii] Murky as the traditional doctrine may be, it is in fact very clear in not admitting adults to Limbo.

Franceschini’s account of Inferno 4, “Dante e il limbo dei pagani,” although titled in such a way as to indicate precise awareness of the newness of Dante’s conception, nonetheless focuses on an unsatisfactory search for a theological precursor, which she attempts to locate in Augustine’s Contra Iulianum.[viii] Padoan had discussed the same text, pointing out that Dante takes as his the position that Augustine discredits.Iulianum.[ix] Emblematic of Franceschini’s resistance to the reality of Dante’s exceptionalism is the conclusion that follows:

Ma è difficile stabilire fino a che punto il limbo descritto nel canto IV, e in particolare l’associazione tra un nutrito gruppo di pagani virtuosi e il limbo, sia sostanzialmente un’invenzione letteraria di Dante o se sia basato su qualche precedente testuale che può essere individuato con certezza (e che sarebbe importante per noi, in quanto attesterebbe una circolazione più ampia dell’idea del limbo dei pagani). (Franceschini, Storia del limbo, p. 87)[x]

[But it is difficult to establish up to what point the Limbo described in canto 4, and in particular the association of a sizable group of virtuous pagans with Limbo, is substantially a literary invention of Dante’s or whether it is based on a textual precedent that we can identify with certainty (and which would be important for us, in as much as it would testify to a more ample circulation of the idea of the Limbo of pagans).]

Franceschini’s clinging to the hope of a textual precedent that has not yet been identified is a feature of Dantean historiography over the centuries: I think, for instance, of the scholars who have expressed the hope that we will find incontrovertible archival “proof” of Brunetto Latini’s homosexuality. Always misplaced as a way of dealing with Dante (who is willing to transform his precursors even when he does have them), in the case of Limbo the hope for a precedent is further belied by Franceschini’s own investigative zeal and precision. Failing to turn up any precedent to Dante’s “invenzione letteraria,” Franceschini’s concluding statement testifies to an unwillingness to credit the role of outsized imagination in the history of ideas.

[i] Giorgio Padoan, “Il Limbo dantesco,” orig. 1969, repr. in Il pio Enea, l’empio Ulisse (Ravenna: Longo, 1977), pp. 101-24, citation p. 105. Translations mine.

[ii] Padoan, “Il Limbo dantesco,” p. 105, note 9.

[iii] Padoan, “Il Limbo dantesco,” pp. 103–4.

[iv] Padoan, “Il Limbo dantesco,” p. 124.

[v] Chiara Franceschini, Storia del limbo (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2017), pp. 76-94.

[vi] In “Contemporaries Who Found Heterodoxy in Dante: Cecco d’Ascoli, Boccaccio, and Benvenuto da Imola on Fortuna and Inferno 7.89,” I analyze the accusation of determinism that Cecco d’Ascoli lodges against Dante vis-à-vis Fortuna, comparing Benvenuto’s robust defense of Dante to Boccaccio’s timid response, in which he deferentially leaves the matter to be decided by the Church.

[vii] “È abbastanza curioso come, di fronte del compito di interpretare le parti della Commedia dedicate al limbo, molti dei lettori, sia antichi sia moderni, abbiano fatto riferimento a una supposta ‘norma,’ una cosiddetta ‘dottrina tradizionale’ che in realtà, come abbiamo visto, era di per sé molto problematica” (Franceschini, Storia del limbo, 78).

[viii] Franceschini, Storia del limbo, p. 87.

[ix] Padoan, “Il Limbo dantesco,” pp. 106-7.

[x] Franceschini, Storia del limbo, p. 87.

Return to top

Return to top