Paradiso 11 begins with an apostrophe to the senseless cares of mortals from which Dante has now been released. In the apostrophe Dante lists the senseless cares that grip men’s souls:

O insensata cura de’ mortali, quanto son difettivi silogismi quei che ti fanno in basso batter l’ali! Chi dietro a iura, e chi ad amforismi sen giva, e chi seguendo sacerdozio, e chi regnar per forza o per sofismi, e chi rubare, e chi civil negozio, chi nel diletto de la carne involto s’affaticava e chi si dava a l’ozio, quando, da tutte queste cose sciolto, con Beatrice m’era suso in cielo cotanto gloriosamente accolto. (Par. 11.1-12)

O senseless cares of mortals, how deceiving are syllogistic reasonings that bring your wings to flight so low, to earthly things! One studied law and one the Aphorisms of the physicians; one was set on priesthood and one, through force or fraud, on rulership; one meant to plunder, one to politick; one labored, tangled in delights of flesh, and one was fully bent on indolence; while I, delivered from our servitude to all these things, was in the height of heaven with Beatrice, so gloriously welcomed.

This passage lists all the forms of professional attainment to which a man could then aspire (a list that has changed remarkably little; what has changed is the membership of the caste of aspirants): the law, medicine, priesthood, rulership, business and politics. The list is framed negatively from the outset, by being placed under the rubric “insensata cura de’ mortali” (senseless cares of mortals). Moreover, a negative spin enters the catalogue of professions when we reach the word “rubare” (to plunder) in verse 7 and continues in the next two verses, which describe delights of the flesh and indolence.

Nonetheless, despite the negative framing, the opening of Paradiso 11 does in fact provide a run-through of the various professions available to the educated male elite of Dante’s day. In this way the poet offers a fascinating contrast to Paradiso 8, where professional attainment is viewed not negatively — as a mortal care from which to be released — but positively, as the glue of the life of the polis.

In Paradiso 8 the context is Aristotelian, and Carlo Martello explicitly refers to Aristotle’s Politics. “Would it be worse for man on earth if he were not a citizen?” in Paradiso 8.115-16 is a question that hearkens back to Aristotle, Politics I.1.2: “homo natura civile animal est” (“Man is by nature a social animal”). In Paradiso 8, the question that follows is: can man be a citizen if there are not different ways of living in society, requiring different talents and duties? The answer is that we need difference in the social sphere, and therefore men are born with different dispositions and talents:

«E puot’ elli esser, se giù non si vive diversamente per diversi offici? Non, se ’l maestro vostro ben vi scrive». (Par. 8.118-20)

“Can there be citizens if men below are not diverse, with diverse duties? No, if what your master writes is accurate.”

Paradiso 8 offers a celebration of different types of professional attainment, while Paradiso 11 views the same professional aspirations as burdensome concerns and celebrates the pilgrim’s release from all such cares.

There is, however, one aspiration that Paradiso 11 will view kindly: to live a life of militant and indeed transformational poverty, in the mode of St. Francis of Assisi. It is to that aspiration and to that lifestyle that this canto now transitions, in the form of a hagiographical tribute to St. Francis and to his “marriage” with Lady Poverty. The metaphor of Francis as the groom of Poverty, his bride, governs the story of his life, as Dante tells it in Paradiso 11.

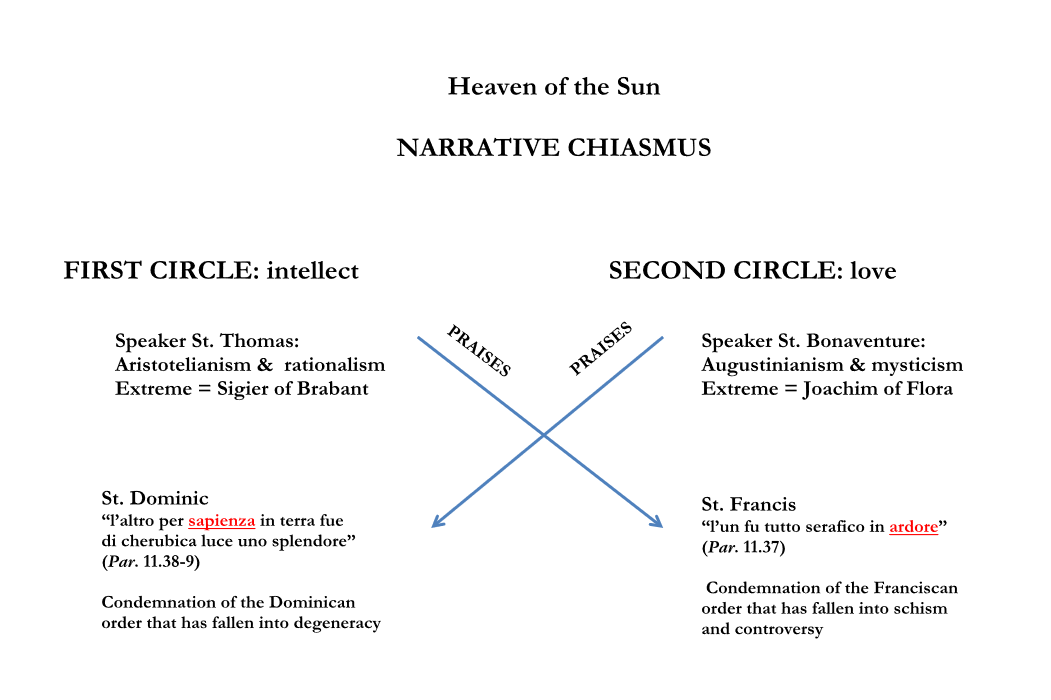

The account of the life of St. Francis is part of the overarching narrative chiasmus that governs the heaven of the sun, as depicted in the following chart:

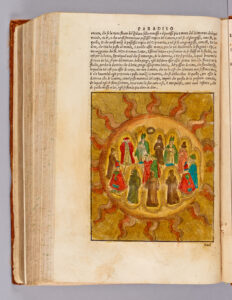

Paradiso 11 offers a great tribute to St. Francis, lover of poverty and founder of the Franciscan order, while Paradiso 12 offers a great tribute to St. Dominic, scholar-warrior and founder of the Dominican order. Neither Francis nor Dominic is present in the heaven of the sun. Rather, two renowned and exemplary members of the orders that they founded, St. Thomas the Dominican and St. Bonaventure the Franciscan, are present and each speaks to the pilgrim. In the chiastic fashion that is typical of the circularized discourse of this heaven, St. Thomas the Dominican will celebrate the life of St. Francis and condemn the degeneracy of the Dominicans (in Paradiso 11), and St. Bonaventure the Franciscan will celebrate the life of St. Dominic and condemn the fracture of the Franciscans (in Paradiso 12).

The “plot” moves forward, as is typical in Paradiso, by way of the articulation of the pilgrim’s uncertainties or “doubts” (“dubbio” in Italian). The hyper-literariness of this heaven, as discussed in Chapter 9 of The Undivine Comedy, is evident from St. Thomas’s presentation of the pilgrim’s queries in the form of verbatim citations of his (Thomas’s) own previous discourse as recorded in Paradiso 10.

Dante’s dubbi take the form of confusion over two obscure statements from St. Thomas’s previous discourse. The first question regards the meaning of the cryptic phrase “U’ ben s’impingua” (where they fatten well) from Paradiso 10.96, here repeated verbatim in Paradiso 11.25. The second question regards the meaning of “Non surse il secondo” (There never rose a second) from Paradiso 10.114:

Tu dubbi, e hai voler che si ricerna in sì aperta e ’n sì distesa lingua lo dicer mio, ch’al tuo sentir si sterna, ove dinanzi dissi “U’ ben s’impingua”, e là u’ dissi “Non nacque il secondo”; e qui è uopo che ben si distingua. (Par. 11.22-27)

You are in doubt; you want an explanation in language that is open and expanded, so clear that it contents your understanding of two points where I said, “They fatten well,” and where I said, “No other ever rose”— and here one has to make a clear distinction.

The second dubbio as expressed above, “Non nacque il secondo” (A second was never born [Par. 11.26]), is a slight variation on Paradiso 10.114, where we found “surse” rather than “nacque”: “a veder tanto non surse il secondo” (a second never rose with so much vision). The second dubbio will not be addressed until Paradiso 13, so we will put it aside and address “U’ ben s’impingua” (where they fatten well).

The replies of the Paradiso frequently range quite far into pre-history before focusing on the target question. In this case the answer to the first dubbio takes the form of a history of the two great orders founded in the thirteenth century, the Franciscans and the Dominicans. We should bear in mind that, when Dante is writing, these two orders are still new among the great religious orders. The Franciscan order was founded in 1209, in which year St. Francis obtained from Pope Innocent III an unwritten approbation of his rule. The Order of Preachers (also known as the Dominican order) was approved in 1216.

The two great mendicant orders, founded recently and contemporaneously, were important rivals in the fabric of urban life in Dante’s time. We think of Florence: on one side of the Duomo is Santa Maria Novella, the Dominican church, and on the other side is Santa Croce, the Franciscan church. The heaven of the sun offers a testimonial to the importance of these orders in cultural terms, an importance that causes Dante to respond to their histories at great length. St. Thomas explains that God ordained two saints to support His church. Embarking on the theme of the equality of these two saints, St. Thomas says that he will speak of Francis, with the understanding however that to praise one of the two great saints is tantamount to praising both:

De l’un dirò, però che d’amendue si dice l’un pregiando, qual ch’om prende, perch’ad un fine fur l’opere sue. (Par. 11.40-42)

I shall devote my tale to one, because in praising either prince one praises both: the labors of the two were toward one goal.

Chapter 9 of The Undivine Comedy analyzes the metanarrative themes of this heaven, which are devoted to problematizing narrative and language: the canti of this heaven explore the impossibility of the trope “to speak of one is to speak of both”. Due to the inescapable temporality of narrative it is not possible to speak of the two saints simultaneously or in the same language; they must be praised sequentially and in different language.

Thus, Dante allocates rhetorical tropes in the life of Francis and the life of Dominic according to a complex compensatory system of “checks and balances”:

If the geographical periphrasis introducing Francis’s birthplace points to the east, “Orïente,” Dominic’s periphrasis points west; if there is etymological wordplay regarding Assisi in canto 11, canto 12 refers to the etymologies of the names of Dominic, his father, and his mother; if Francis’s birthplace is a rising sun, an “orto” (11.55), Dominic is the cultivator of Christ’s garden, Christ’s “orto” (12.72, 104). This same principle of balance informs the metaphors that govern the vite : if Francis is portrayed chiefly as a lover and a husband, and if we think of his life in terms of the mystical marriage to Poverty, nonetheless Dominic’s baptism is characterized as an espousal of faith and he is “l’amoroso drudo / de la fede cristiana” (“the amorous lover of the Christian faith” [12.55-56]); if Francis’s life is modeled on Christ’s, nonetheless the poem’s first triple rhyme on “Cristo” belongs to the life of Dominic (12.71, 73, 75). In writing the life of Dominic, Dante seems to have been intent on picking up the rhetorical and metaphorical components of the life of Francis: if Francis is an “archimandrita” (11.99), a prince of shepherds in an ecclesiastical Greek locution, Dominic is not only “nostro patrïarca” (11.121), a term that displays the same linguistic provenance, but also a “pastor” (11.131), whose sheep are wandering from the fold. Although we think of Dominic as the more military, and of Francis as the more loving, in fact Francis is a campione as well as Dominic, and Dominic is a lover as well as Francis. Even the agricultural images of Dominic as the keeper of Christ’s vineyard and as a torrent sent to root out heretical weeds are anticipated by Francis’s return “al frutto de l’italica erba” (to the harvest of the Italian fields [11.105]) and reprised in the image of the Franciscans as tares that will be excluded from the harvest bin. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 199)

Below is a chart that breaks down the eulogies to Francis and to Dominic (this chart is p. 217 of The Undivine Comedy), showing how carefully Dante orchestrates the rhetorical balancing of the two saints. There are also two outlines of the heaven of the sun, showing the complex interplay of these elements: the presentations of the two circles of souls, the pilgrim’s queries and the replies, the hagiographies followed by the critiques.

The life of St. Francis parses the major milestones of the saint’s life as Dante construes them: Francis’s birth in Assisi, his break from his father due to his “marriage” with Lady Poverty, his first followers, Pope Innocent III’s oral approval of the Order of Friars Minor, the further formal approval of Pope Honorius III, the “quest for martyrdom” that prompted him to attempt to convert the Sultan of Egypt, and finally his receipt of the stigmata two years before his death. Dante’s account stresses the Saint’s passionate love affair with Lady Poverty.

It is worth noting that the Sultan at whose court Saint Francis attempted to carry out his missionary work, al-Malik al Kamil (1179-1238), was the son of the brother of Saladin, the general and first Sultan of Egypt and Syria (c. 1137 – 4 March 1193). Dante places Saladin among the virtuous pagans in his Limbo.

The hagiography of Francis is followed by a coda on the decadence of the Dominican order, which will finally address directly the pilgrim’s dubbio (“U’ ben s’impingua” in Par. 10.96 and Par. 11.25). The answer to Dante’s uncertainty: Dominicans used to “fatten” when they were good sheep, before they began to stray.

Return to top

Return to top