- how to tell time in Purgatory: by relating it to time on earth

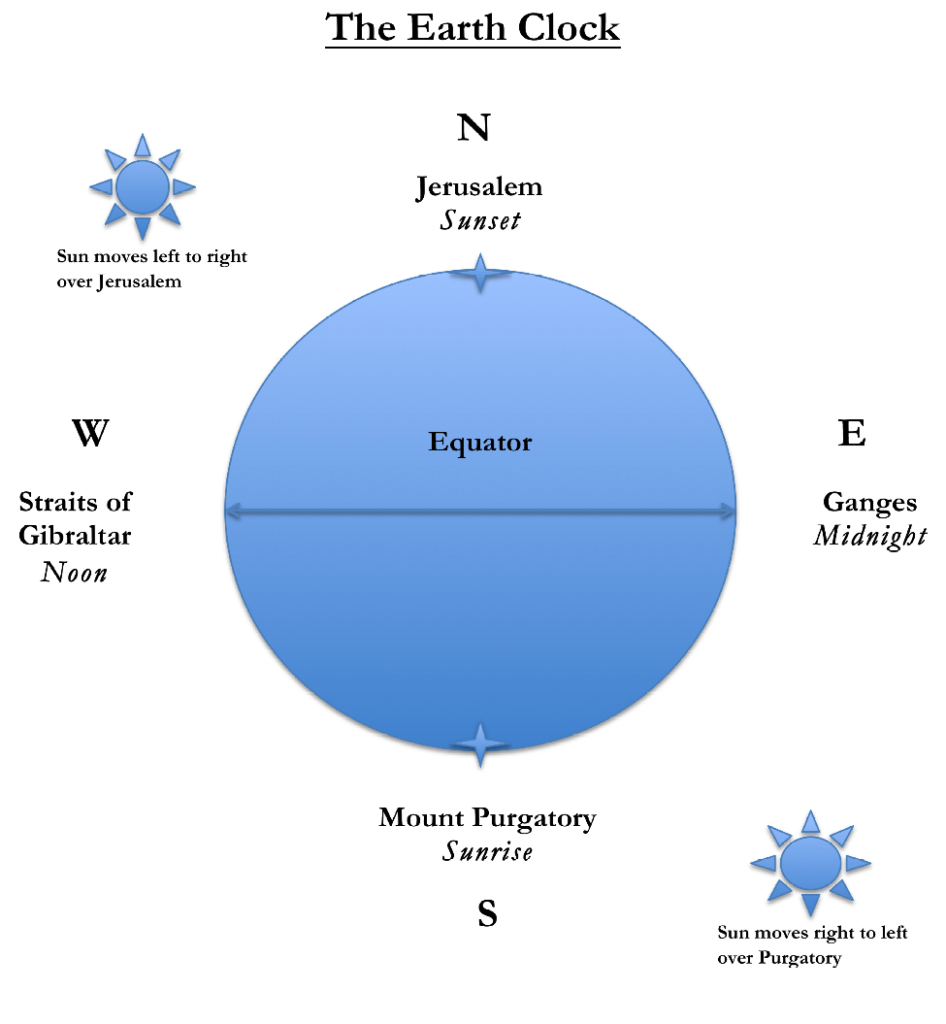

The astronomical periphrasis at the beginning of Purgatorio 2 introduces us to the “earth clock” (see the below chart). Dante-poet tells time in Purgatory always in relation to the time at different points on the earth’s circumference: sunrise in Purgatory is noon at the Straits of Gibraltar, sunset in Jerusalem, and midnight at the river Ganges. In this way, Dante positions the action of Purgatorio with respect to time on earth, always reminding us that Purgatory is earth-like in a way that is not true of the other two realms.

Unlike Hell and Heaven, which are eternal, Purgatory is located on the earth, in the southern hemisphere, and exists in time, just like the lands of the northern hemisphere. By the same token, Purgatory will cease to exist at the end of time. At the Last Judgment all the souls who travel through Purgatory on their way to Paradise will be saved, and there will be no further need of a place in which saved souls must work to purify themselves before ascending to beatitude.

As discussed in the Commento on Purgatorio 1, the apparently triune structure of this afterworld thus overlays a fundamentally binary structure: at the end of time, after the Last Judgment, all souls will be either damned and in Hell for all eternity, or they will be saved and in Paradise for all eternity. No one will any longer be making use of the (temporary) services of Purgatory.

Let me state again: everyone who arrives in Purgatory is already saved. However many thousands of years a given soul might require for its purgation — for although there are particular sufferings coordinated to particular vices, the true currency of Purgatory is time spent in the second realm — every soul who comes to this place will be saved when time comes to an end.

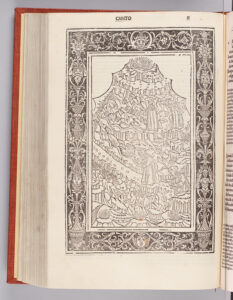

Purgatory is a way-station for saved souls, a place and a condition in which an already saved soul works to be completely freed from the underlying impulses that lead to sin. By means of its journey up the mountain, a soul that is saved when it arrives in Purgatory is made, as in the last verse of Purgatorio, “pure and prepared to climb unto the stars”: “puro e disposto a salire alle stelle” (Purg. 33.145).

All of these fundamental principles are implied by the simple narrative expedient of telling time on Purgatory in a way that always coordinates with the time on earth.

We living humans share both space and time with the dead souls of Purgatory. Spatially, living humans dwell in the land-filled northern hemisphere of the globe that we share with Purgatory. The mountain of Purgatory is located in the watery southern hemisphere, at the antipodes of Jerusalem, which is at the center of the northern hemisphere.

The air we breathe on earth is the same air that the souls of Purgatory no longer need to breathe.

Both northern and southern hemispheres exist in time. The long astronomical periphrasis that opens this canto is a way of communicating that time is a constituent feature of this realm — just as it is on earth.

Most of all, in terms of the melancholy sweetness that suffuses the second realm, especially in the opening canti, the earth clock is a punctual reminder of the umbilical cord that connects the souls of Purgatory to those they left behind on earth.

The early canti of Purgatorio are awash in nostalgia for our humanity as experienced on earth: non-sublimated, corporeal, of the living.

Hence we encounter, in this canto, a dead soul who seeks to behave as though he were alive. And, in canto after canto, the dead souls whom we encounter on the lower shoulders of Mount Purgatory — in the first eight canti of Purgatorio — remember and virtually caress their human bodies with palpable nostalgia and affection.

* * *

Purgatorio 2 is a canto of intense intertextuality, focused on two very different songs: one a biblical Psalm, the other a contemporary Italian canzone. Dante refers to the two songs in question by citing their incipits or first verses (the word “incipit” means “it begins” in Latin). The incipit or first verse of a poem functioned as a title in Dante’s time.

The two poems, both sung, that are cited through their incipits in Purgatorio 2 are: first the biblical Psalm In exitu Israel de Aegypto and next the vernacular love poem Amor che nella mente mi ragiona, written by Dante himself.

The psalm is sung by souls who are being sailed to purgatory by an angel-helmsman. Dante’s friend Casella will explain later in the canto that all souls bound for Purgatory gather and are picked up by the angelic craft at the mouth of the Tiber (Purg. 2.100-05). The psalm’s theme of the Exodus, the flight of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt, clearly resonates to the theme of Purgatory as a quest to leave bondage for freedom.

Among the souls who disembark on the shore of Purgatory is Dante’s friend Casella. A strong Vergilian intertextuality suffuses the encounter with Casella. The poignant language of Dante’s attempt to embrace his friend only to find that he is an intangible shade is based on the melancholy passages of Aeneid 6 in which Aeneas tries to embrace his lost loved ones:

Ohi ombre vane, fuor che ne l’aspetto! tre volte dietro a lei le mani avvinsi, e tante mi tornai con esse al petto. (Purg. 2.79-81)

O shades — in all except appearance — empty! Three times I clasped my hands behind him and as often brought them back against my chest.

The pilgrim asks Casella to sing for him an “amoroso canto” (a song of love [Purg. 2.107]), as was his wont on earth, and Casella complies by singing the first verse of a canzone: “Amor che ne la mente mi ragiona” (Love that discourses to me in my mind [Purg. 2.112]). The canzone Amor che nella mente is a love canzone that Dante had previously placed in his philosophical treatise Convivio, where he claims that the lady addressed is Lady Philosophy; it is the first of three of his own canzoni that Dante inserts into the Commedia. The first chapter of Dante’s Poets, “Autocitation and Autobiography,” is an interpretation of what Dante means to signify with the three self-citations or “autocitations” of his own canzoni in the Commedia. In “Autocitation and Autobiography”, I attempt to decode both what is intended by the choice of canzoni and what is intended by their placement within the overall narrative structure.

Through the figure of Casella, the poet introduces to the Purgatorio the great theme of friendship: there is no theme that has deeper roots in Dante’s poetry than that of male friendship, particularly friendship among poets and artists (see the sonnet Guido, i’ vorrei che tu e Lapo ed io and my commentary in Dante’s Lyric Poetry: Poems of Youth and of the Vita Nuova). The theme of friendship in Purgatorio is tightly linked to the enduring connection that the souls still feel to their bodies. Casella beautifully expresses this connection, when he tells Dante that the love that he felt for him “within my mortal flesh” — “nel mortal corpo” (Purg. 2.89) — is what he feels for Dante now, “freed from his body”:

Rispuosemi: «Così com’io t’amai nel mortal corpo, così t’amo sciolta: però m’arresto; ma tu perché vai?». (Purg. 2.88-90)

He answered: “As I loved you when I was within my mortal flesh, so, freed, I love you: therefore I stay. But you, why do you journey?”

But the real connection between the two men does not mean that Dante can embrace his friend. When he tries, his attempt is thwarted, for Casella’s body is an insubstantial image that cannot be embraced. Why is Dante able to pull the hair of Bocca degli Abati in Inferno 32 but not able to embrace Casella in Purgatorio 2? In Inferno 32 Dante is functioning as a deliverer of infernal torment, a minister of divine justice, and his ability to touch Bocca is purely instrumental. The attempt to embrace Casella, in contrast, reveals the inability to express human love in a human fashion — in embodied fashion — once past the threshold of death.

Those who stop to listen to Casella sing are lulled by the beauty of the song, until Cato breaks in upon the reverie at canto’s end with a sharp rebuke:

qual negligenza, quale stare è questo? Correte al monte a spogliarvi lo scoglio ch’esser non lascia a voi Dio manifesto. (Purg. 2.121-23)

What negligence, what lingering is this? Quick, to the mountain to cast off the slough that will not let you see God show Himself!

This will be the dynamic of Purgatorio: the love of the two friends who embrace each other, only to find their hands come up empty; the beauty of the love song that the souls linger to listen to, only to find that they are late for their appointment with paradise. Here we see the failures and the corrections of attempts to embrace the human: this is Purgatory after all, and there is a job to do. But before the failure and the correction, Dante employs beautiful language to describe and indeed caress the warmth of human affection and the beauty of human art. In this language resides the special bitter-sweet music of Purgatorio: its music dwells precisely in its embrace of the human, caressed in this cantica as nowhere else in Dante’s poem.

Return to top

Return to top