- Inferno 19 boasts a high style marked by many apostrophes — including the canto opening — and much metaphoric language

- the prostituting of the Church-bride by her Pope-bridegroom picks up and metaphorizes the sexualized language of Inferno 18

- reference to the capital punishment of propaginazzione in verses 49-51; see the Commento on Inferno 27 for discussion of the historical tortures and punishments referenced in the Commedia

- the intense dialogic quality recalls Inferno 10, where too dialogue is a font of pain and misunderstanding

- Dante manufactures a way to signal Boniface VIII’s damnation before his death in 1303, thus effectively disregarding the theology of repentance (see Inferno 20, Inferno 27, and Purgatorio 5)

- Dante thereby comes close to a deterministic position, eliding Boniface’s ability to exercise his free will

- St. John, author of the Apocalpyse?

- the Donation of Constantine and its eventual debunking by the philologist Lorenzo Valla: one of the great examples of the importance of philology, the discipline of the historicized understanding of language

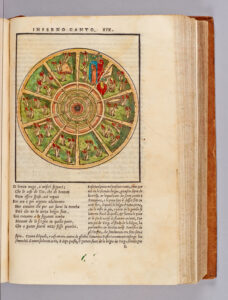

[1] Inferno 19 is the Commedia’s first full-fledged indictment of the Church, picking up on some earlier indications that Dante links the clerical establishment with the sin of avarice. We remember especially the following verses from Inferno 7, where Dante says that he sees cardinals and popes among the misers in the fourth circle:

Questi fuor cherci, che non han coperchio piloso al capo, e papi e cardinali, in cui usa avarizia il suo soperchio. (Inf. 7.46-48)

These to the left—their heads bereft of hair— were clergymen, and popes and cardinals, within whom avarice works its excess.

[2] The third bolgia is devoted to the type of fraud called simony, in which spiritual things (“le cose di Dio” or “things of God” of verse 2) are sold or exchanged for temporal things:

Simony is usually defined “a deliberate intention of buying or selling for a temporal price such things as are spiritual or annexed unto spirituals”. While this definition only speaks of purchase and sale, any exchange of spiritual for temporal things is simoniacal. Nor is the giving of the temporal as the price of the spiritual required for the existence of simony; according to a proposition condemned by Innocent XI (Denzinger-Bannwart, no. 1195) it suffices that the determining motive of the action of one party be the obtaining of compensation from the other. (“Simony,” from The Catholic Encyclopedia, accessed 10/27/2015)

[3] Simon Magus, from whom simony gets its name, is a figure in the New Testament. Acts 8:9-24 recounts Simon’s attempt to buy from St. Peter the power to grant the Holy Spirit through the laying on of hands:

Simon, seeing that the Holy Spirit was granted through the imposition of the apostles’ hands, offered them money; let me too, he said, have such powers that when I lay my hands on anyone he will receive the Holy Spirit. Whereupon Peter said to him, take thy wealth with thee to perdition, thou who hast told thyself that God’s free gift can be bought with money. (Acts 8:18-20)

[4] Inferno 19 is a stunning canto, metaphorically and dramatically elaborate. It begins explosively, with a dramatic apostrophe to Simon Magus and his followers, all those who prostitute for gold and silver the “things of God, that ought to be the brides of righteousness”:

O Simon mago, o miseri seguaci che le cose di Dio, che di bontate deon essere spose, e voi rapaci per oro e per argento avolterate, or convien che per voi suoni la tromba, però che ne la terza bolgia state. (Inf. 19.1-6)

O Simon Magus! O his sad disciples! Rapacious ones, who take the things of God, that ought to be the brides of Righteousness, and make them fornicate for gold and silver! The time has come to let the trumpet sound for you; your place is here in this third pouch.

[5] Here, at the beginning of Inferno 19, Dante inaugurates the key theme of innocence that is wantonly corrupted by its alleged protectors: the metaphor of a bride who is prostituted by her bridegroom runs throughout the canto. Here the “things of God” that should be “brides of righteousness” are not protected by those charged to protect them, the men of the Church. Rather, “the things of God / that ought to be the brides of Righteousness” — “le cose di Dio, che di bontate / deon essere spose” (Inf. 19.2-3) — are prostituted: sold for money, debased, and corrupted.

[6] Because this opening is couched as an apostrophe to Simon Magus and his followers, as direct address, the indictment rings out in the second person plural: “e voi rapaci / per oro e per argento avolterate” (and you rapacious ones / prostitute them for gold and silver [Inf. 19.3-4]). The second person plural pronoun “voi” is repeated in verse 5, where the poet tells the simonists that his trumpet sounds for them, the inhabitants of his third bolgia: “or convien che per voi suoni la tromba, / però che ne la terza bolgia state” (The time has come to let the trumpet sound / for you; your place is here in this third pouch [Inf. 19.5-6]). The repeated voi initiates the intensely dialogic nature of Inferno 19.

[7] Ultimately, in this canto, the “spose” will cease to be plural and generic “brides of righteousness” and will become a singular bride: the Church, prostituted not by generic simonists, but by her very own bridegroom, the Pope. Dante thus uses the bolgia of simony to indict the Church in its very pinnacle of power and authority: the papacy. By putting two popes into the bolgia of simony, one who speaks to Dante and another whose coming is foretold, Dante indicts the papacy itself.

[8] Moreover, the metaphor of the Church as a bride prostituted by her Pope-bridegroom is all the more effective coming as it does after the prostituted sister (Ghisolabella, prostituted by her brother Venedico Caccianemico) and the pregnant abandoned bride (Hypsipyle, seduced and abandoned by Jason) of Inferno 18.

[9] In The Undivine Comedy I discuss the progression from the relatively plain and unadorned language of Inferno 18 (“puttana” in Inf. 18.133 refers to the literal “whore” Thaïs) to the densely metaphoric fabric of Inferno 19 (“puttaneggiar coi regi” in Inf. 19.108 refers to the whoring of the Church):

Again, the point is the stylistic discrepancy between the two cantos: from the relatively simple, unadorned, plain style of canto 18 to the rhetorical profusion of canto 19. The transition from a literal and rhetorically unelaborated style to a language of great metaphorical density finds its emblem in the transition from the literal “puttana” of 18.133, Thaïs, to the metaphorical “puttaneggiar coi regi” (whoring with kings [19.108]) of the Church on behalf of the pimping popes. The back-to-back use of puttana and puttaneggiar (the former used only twice more, both times in Purgatorio 32 for the Church, the latter a hapax), underscores the transition from literal to metaphorical whoring and thus the rhetorical differences between cantos: the straightforward narrative of Inferno 18 contrasts sharply with the grandiloquence of Inferno 19, a canto that contains three apostrophes, that indeed opens with the apostrophic trumpet blast directed at Simon Magus and his fellow prostituters of “the things of God.” (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 77-8)

* * *

[10] In this canto of high drama as well as of high language, Dante does not simply view the sinners in their respective bolgie but participates in an animated dialogic encounter with Pope Nicholas III, who mistakes Dante for a later pontiff, Boniface VIII. Nicholas III, the Roman nobleman Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, Pope from 1277 to 1280, is now in the bolgia of simony, head-first in a cleft in the rock floor, only his feet visible. Since he is buried head-first, Nicholas III cannot see the figure standing above him and as a result he mistakes Dante for the man whom he expects, whose arrival will push him further into the rock and who will take his place as the upper-most of the upside-down popes wedged deeply into the very floor of Hell.

[11] The narrator describes his own posture during the colloquy with Nicholas III. He stands above the soul who is wedged into the rock floor of Hell and compares himself to “’l frate che confessa” (the friar who confesses), the friar who stands above a man who is condemned to death by propagginazione. This is the ghastly torture of being buried alive, head down, resulting in the suffocation of the condemned:

Io stava come ’l frate che confessa lo perfido assessin, che, poi ch’è fitto, richiama lui per che la morte cessa. (Inf.19.49-51)

I stood as does the friar who confesses the foul assassin who, fixed fast, head down, calls back the friar, and so delays his death.

[12] The torture of propagginazione will be discussed in the context of other references to contemporary capital punishment in the Commedia in the Commento on Inferno 27.

[13] The successor pope to whom Nicholas III thinks he is speaking is Pope Boniface VIII, born Benedetto Caetani. Boniface VIII became pope fourteen years after the death of Nicholas III, in 1294, and remained head of the Holy See until his death in 1303. Boniface VIII succeeded the holy hermit, Pietro da Morrone, who was Pope Celestine V for five months in 1294 before he became the first pope to resign his office. Many, like the Franciscan poet Jacopone da Todi, hoped that the pious and humble Celestine V would be erhable to reform the Church, a cause that was set back by the “usurpation” of the papacy by the worldly Boniface VIII. On Celestine V and his candidacy to be the unnamed soul “che fece per viltade il gran rifiuto” (who made, through cowardice, the great refusal [Inf. 3.60]), see the Commento on Inferno 3.

[14] Nicholas III indicates his great surprise at what he considers Boniface VIII’s premature arrival to the bolgia of simony, agitatedly asking “are you already here” — “Se’ tu già costì ritto, / se’ tu già costì ritto, Bonifazio?” (Are you already standing, / already standing there, o Boniface? [Inf. 19.52-3]) — and then adding that the book of the future has lied to him by several years: “Di parecchi anni mi mentì lo scritto” (The book has lied to me by several years [Inf. 19.54]). Nicholas’ amazement at thinking Boniface is present is legitimate: this scene takes place in April 1300, and Boniface does not die until October 1303. Perhaps Nicholas should have known better: the “writing” — “lo scritto” of verse 54 — in which he read the true date of Boniface’s death is God’s writing, and the book of God’s Providence cannot lie. On the other hand, we learned in Inferno 10 that the sinners see the future only dimly, “come quei c’ha mala luce” (like those who have poor light [Inf. 10.100]), that their ability to see the future decreases as the event draws nearer, and that they cease to see altogether when it becomes the present (Inf. 10.100-105).

[15] Nicholas III proceeds to speak mordantly to the man standing above him, whom he mistakenly believes to be Boniface VIII, accusing him of having deceived the Church and then prostituted her. In the following verses, the Church is the “beautiful lady” — “la bella donna” of verse 57 — whom Boniface VIII (according to the accusation of Nicholas III) first “took by deceit” (“tòrre a ’nganno” = togliere con l’inganno) and then violated (fare strazio di):

Se’ tu sì tosto di quell’aver sazio per lo qual non temesti tòrre a ’nganno la bella donna, e poi di farne strazio? (Inf. 19.55-57)

Are you so quickly sated with the riches for which you did not fear to take by guile the Lovely Lady, then to violate her?

[16] In Nicholas III’s denunciation, Boniface VIII becomes the metaphoric conflation of two sinners from Inferno 18. In the Boniface VIII who is evoked and described by Nicholas III, we find metaphorized and blended the sins of Jason and Venedico Caccianemico:

- Boniface VIII first deceives his bride, taking her by deceit (“tòrre a ’nganno” in verse 56), like Jason, whose seduction of Hypsipyle is characterized by the same deceit, inganno (“Ivi con segni e con parole ornate / Isifile ingannò” [Inf. 18.91-2]).

- Boniface VIII then prostitutes her, like Venedico Caccianemico, who prostituted his sister Ghisolabella, whose very name “Ghisolabella” is echoed in the description of the Church as “la bella donna” in verse 57.

[17] The dialogue between Nicholas III and the pilgrim provides, first, a stunning accusation directed by one simoniac Pope (present and stuffed into the ground) at another simoniac Pope (mistakenly deemed to be present and standing above him). The accusation leveled by Nicholas III picks up on the canto’s opening salvo against those who prostitute “le cose di Dio” for gold and silver and indicts Boniface on two counts: he took the Church by force and he prostituted her, violating her purity.

[18] The dialogue between the soul of Nicholas III and the man he believes is Boniface VIII is also part of an extraordinary dramatic conceit concocted by the narrator in order to damn a Pope who was still alive in 1300.

[19] Boniface VIII did not die until 1303, while — as we know — the fictive date of the pilgrim’s journey into Hell is April 1300. Dante, writing this canto years after Boniface’s death on 11 October 1303, wants to find a way to indicate that Boniface’s abode is Hell, while not committing the error as author. The solution is that Nicholas III, who is stuck head-first into the rock and cannot see, mistakenly identifies the pilgrim as Boniface VIII and addresses him by name, using direct discourse: “Se’ tu già costì ritto, / se’ tu già costì ritto, Bonifazio?” (Are you already standing, / already standing there, o Boniface? [Inf. 19.52-3]). Dante-poet thus “covers” himself by having Nicholas be the one to indicate his surprise at Boniface’s premature arrival in Hell:

Ed el gridò: “Se’ tu già costì ritto, se’ tu già costì ritto, Bonifazio? Di parecchi anni mi mentì lo scritto.” (Inf. 19.52-54)

And he cried out: “Are you already standing, already standing there, o Boniface? The book has lied to me by several years.”

[20] Later in Inferno 19 Dante-pilgrim worries that he might have been “troppo folle” (too rash [Inf. 19.88]) in the outburst that he directs at Nicholas III. This is a good example of the poet defusing his own boldness by projecting it onto the pilgrim. For the truly rash act of Inferno 19 is the one executed by Dante-poet, who effectively reserves a place in Hell for Boniface VIII.

[21] In damning Boniface VIII, Dante sets aside the theology of repentance, which holds that sinners can delay repentance until the very last moment of life and still be saved. Dante is highly aware of this doctrine and indeed dramatizes late repentance and consequent salvation in Purgatorio 5. By damning Boniface before he died in 1303, Dante effectively denies him the possibility of repentance in extremis; indeed, he denies him the use of the last three years of his life. Most important, he denies Boniface’s free will, the agency gifted by God that allows sinners to repent and convert to the good throughout life, as long as one is alive.

[22] Within a poem whose premise of knowing the afterlife is by definition deterministic, Dante flirts here — through the trope of damning Boniface three years before his historical death in 1303 — with a more specific and technical determinism: that practiced by astrologers and diviners. This more technically construed determinism is precisely the topic of Inferno 20. For further discussion of Boniface VIII in this context, see the Commento on Inferno 20 and Inferno 27. For Cecco d’Ascoli’s imputation of the sin of determinism to Dante, his accusation that Dante did not sufficiently prize free will, see the Commento on Inferno 7.

[23] In “pre-damning” Boniface VIII to Hell, Dante sets aside the theology of repentance and comes perilously close to a deterministic position, eliding from the picture Boniface’s ability to exercise his free will in order to repent.

* * *

[24] We have seen that the capacity of words to wound or to misrepresent is a feature of dialogue in Inferno: dialogue is essential to all human interaction, but it can therefore also be a source of misunderstanding and hurt. In Inferno 10 Cavalcanti père misconstrues the pilgrim’s past absolute “ebbe” in verse 63 (“forse cui Guido vostro ebbe a disdegno”), taking the tense of the verb as a sign that his son Guido is dead: “Come? / dicesti ‘elli ebbe’? non viv’elli ancora?” (What’s that? / He ‘did disdain’? He is not still alive? [Inf. 10.67-8]).

[25] The pilgrim hesitates in responding to the father in Inferno 10, because he doesn’t understand how Cavalcanti senior had arrived at his mistaken assumption. Here too, in Inferno 19, the pilgrim hesitates in responding to Nicholas III. After all, it’s not every day in Hell that one is mistaken for a Pope! His hesitation is sufficiently prolonged that Virgilio intervenes, telling Dante precisely what to say to Nicholas: “Dilli tosto: / ‘Non son colui, non son colui che credi’” (Tell this to him at once: / ‘I am not he — not who you think I am’ [Inf. 19.61-2]).

[26] The dialogic nature of this canto and of this encounter is distilled in these verses, in which the narrator does not permit the pilgrim to simply respond to Nicholas. Rather the narrator briefly stops the dialogue, creating an urgent pause, and then has Virgilio present to Dante, in embedded direct discourse, the very words that he should speak to Nicholas III. The poet does not write “Tell him that you are not the one he thinks you are”, employing indirect discourse (Tell him that . . .), but rather “Tell him: ‘I am not he — not the one you think I am’”, employing direct discourse. The rhythm of this passage, the excited cadence of Nicholas III who thinks he is addressing Boniface VIII, the pilgrim’s confused pause, the urgency of Virgilio’s instruction so as to preclude further misunderstanding — all these features testify to Dante’s brilliance as a stager of dialogue and to his continuing meditation on the interstices and complexities of human communication. For a similar dialogic moment, see the Commento on Inferno 9 on the opening of that canto.

[27] When the pilgrim realizes that he is speaking to the very custodian of the Church-bride, to her Pope-bridegroom, he is emboldened to speak harsh words of censure to Pope Nicholas, beginning in Inferno 19.90. We remember that, in the simile of verses 49-51, the narrator describes himself as like the “friar who confesses” in his posture toward this sinner. All the more appropriate, then, that the pilgrim appropriates biblical language for his harsh reproof, at a certain point in his tirade citing the New Testament and specifically the visions of the Apocalypse:

Di voi pastor s’accorse il Vangelista, quando colei che siede sopra l’acque puttaneggiar coi regi a lui fu vista... (Inf. 19.106-108)

You, shepherds, the Evangelist had noticed when he saw her who sits upon the waters and realized she fornicates with kings...

[28] In the above passage Dante calls the author of the Apocalypse “the Evangelist” or writer of the Gospel: “il Vangelista” (Inf. 19.106). Dante is not confused; rather he is showing lack of historical knowledge. In Dante’s time John the Evangelist was believed to be the author of the Apocalypse, as well as the author of the Gospel of John. There was as yet no knowledge of John of Patmos.

[29] John’s visions in the King James version of the Bible include the following: “I will shew unto thee the judgment of the great whore that sitteth upon many waters: With whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication” (Revelation 17:1-2). Dante invokes this passage from the Apocalypse (also known as Revelation), telling Nicholas that the Evangelist had become aware of “pastors” like him when he saw “the whore who sits upon the waters” engaged in “fornicating with kings”: “quando colei che siede sopra l’acque / puttaneggiar coi regi a lui fu vista” (Inf. 19.107-8).

[30] The “meretrix magna” of Apocalypse 17:1-3 was interpreted in antiquity as a reference to Rome. John of Patmos, in other words, was attacking Rome with the slur “the great whore that sitteth upon many waters”. However, medieval Christians, especially in the milieu of reformers like the spiritual Franciscans, interpreted the whore who sits upon the waters as a reference to the corrupt and wealthy Church. The extraordinary verb puttaneggiare of verse 108 (“puttaneggiar coi regi” — “whoring with kings”) thus concludes the traslatio from literal pimps and whores in Inferno 18 to metaphorical pimps and whores in Inferno 19: from Venedico Caccianemico, the pimp of his sister, and Thaïs, the “puttana” of Inferno 18.133, to the pimping Popes who make the Church a whore engaged in “puttaneggiar coi regi” in Inferno 19.108.

[31] Dante-pilgrim concludes his tirade with an apostrophe to the Emperor Constantine, beginning in Inferno 19.115:

Ahi, Costantin, di quanto mal fu matre, non la tua conversion, ma quella dote che da te prese il primo ricco patre! (Inf. 19.115-17)

Ah, Constantine, what wickedness was born— and not from your conversion—from the dower that you bestowed upon the first rich father!

[32] Here initiates another long and critically important thematic thread of the Commedia: the idea that the corruption of the Church began when Emperor Constantine, who ruled from 306 to 337 CE, departed for Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). It was believed that Emperor Constantine, having been cured by Pope Sylvester of leprosy, in gratitude bequeathed the Western Roman Empire to the Church, as a parting “dowry” for the Church (“dote” in verse 116, continuing the canto’s bridal metaphor). According to this view of history, current in Dante’s time, Pope Sylvester thus received from Constantine on behalf of the Papacy a vast empire and a vast fortune.

[33] The Papal claim to temporal power was based on the so-called Donation of Constantine. This document, which purports to bequeath Rome and its empire to the Church, was held in Dante’s time to be a legal document written in Constantine’s court. In reality it was written in the papal curia centuries after Constantine’s time and ultimately became known as “the most important forgery of the Middle Ages”:

Donation of Constantine, Latin Donatio Constantini and Constitutum Constantini, the best-known and most important forgery of the Middle Ages, the document purporting to record the Roman emperor Constantine the Great’s bestowal of vast territory and spiritual and temporal power on Pope Sylvester I (reigned 314–335) and his successors. Based on legends that date back to the 5th century, the Donation was composed by an unknown writer in the 8th century. Although it had only limited impact at the time of its compilation, it had great influence on political and religious affairs in medieval Europe until it was clearly demonstrated to be a forgery by Lorenzo Valla in the 15th century.

(“Donation of Constantine,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 10/27/2015; the fresco shows Sylvester [left] receiving the purported donation from Constantine [right], in Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome, 13th century)

[34] Dante deplores the Donation of Constantine, believing that the corruption of the Church and its inability to follow in the footsteps of Christ and live according to His mandate of evangelical purity are the result of the enormous temptations and mistaken priorities generated by so vast a material gift. In Dante’s view, the Donation of Constantine corrupted the Church: the dowry corrupted the bride.

[35] In Dante’s view the Church was effectively submerged by earthly goods and by the pernicious desire to possess those goods, as a direct consequence of Constantine’s well-intentioned but maleficent gift. Dante makes his views known throughout the Commedia:

- In Purgatorio 32, a canto that is in effect Dante’s personal version of the Apocalypse, he has a vision of the Church as a chariot that is submerged in eagle’s feathers (Purg. 32.124-29). The feathers represent the corrupting material goods that came to the Church via the imperial eagle and through the Donation of Constantine.

- In Paradiso 6, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, who reigned from 527 to 565, tells the story of the Roman Empire, and he refers to Constantine’s transferral of the seat of the Roman Empire from Rome to Constantinople in 330 as going “contr’al corso del ciel” — “counter to heaven’s course”: “Poscia che Costantin l’aquila volse / contr’ al corso del ciel” (After Constantine had turned the Eagle / counter to heaven’s course [Par. 6.1-2]).

- At the same time, Constantine’s good intentions will be specifically vindicated in Paradiso 20 when the pilgrim sees the soul of the Emperor twinkling among the lights of the eagle of justice. The eagle will describe Constantine as the one “whose good intention bore evil fruit”: “L’altro che segue, con le leggi e meco, / sotto buona intenzion che fé mal frutto, / per cedere al pastor si fece greco” (The next who follows — one whose good intention / bore evil fruit — to give place to the Shepherd, / with both the laws and me, made himself Greek (Par. 20.55-7).

[36] The skills and knowledge that eventually debunked the centuries-long conspiracy that is the Donation of Constantine were rooted in a new ability to historicize language acquired by the humanists of the Quattrocento. If Dante had lived a few centuries later, he would have witnessed the great Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla (1407-1457) use newly acquired philological knowledge to attack the authenticity of the Donation of Constantine. Lorenzo showed that the Latin of the Donation of Constantine was not the Latin of Emperor Constantine’s fourth century. The Donation of Constantine was a forgery written in the papal court circa 750-800 CE, long after the reign of Emperor Constantine.

[37] Valla conclusively debunked the document on which the Church’s claims to temporal rule in the West were based. This heroic undertaking was enabled by the new discipline of philology: a discipline based on a historicized understanding of language that was not yet fully evolved in Dante’s time.

[38] Dante, having no basis to believe the document fraudulent and illegal, could only kick and scream against its contents.

![Donation of Constantine [Credit: ]](https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/130676-004-3A865E17-300x217.jpg)

Return to top

Return to top