- detheologizing clears the way for historicizing

- the role of the family in dynastic politics: in Inferno we move from Francesca, a dynastic wife, to Ugolino, a dynastic wolf

- the Ugolino episode highlights the toxic effects of subordinating love to the demands of power

- Dante defies the social order, claiming that Ugolino’s children are not guilty by association with their father

- Sardinia in the Inferno: from the barraters of Inferno 22 to the traitors of Inferno 33

- language and consolation

- the theologically unorthodox category of zombies, the “undead”: Dante again flirts with the determinism of which Cecco d’Ascoli accused him

- the zombie concept is based in popular culture and a non-theological dualistic stance toward body and soul (the soul is in Hell while the body remains on earth)

- the theme of animated death looks forward to Lucifer and Inferno 34

- the use of the undead category to manipulate the suspension of disbelief

[1] While writing the pages on Ugolino della Gherardesca in The Undivine Comedy (1992), my analytical lens shifted from the meta-narrative to include more historicist material (see pp. 96-97). In retrospect I realize that writing these pages was perhaps the first time I experienced in practice how detheologizing clears the way for historicizing, long before I understood in theoretical terms how this is in fact the case. In making my case for historicizing, I do not mean to suggest that history has not been amply used in considerations of the Commedia, but to indicate that we can see the possibilities for historicist readings in a fresh light once we are less blinkered by an overdetermined hermeneutic template engineered by the author to prescribe our readings.

[2] Thus, in the essay “Only Historicize” (2009), I give the example of what was then the still under-explored historical context of Ugolino, stressing the Ugolino episode as the Inferno’s most painful exploration of the role of family in politics: “Dante’s thinking on the role of the casato as a key to the tragedy of Italian history is an unexplored feature of the Ugolino episode” (“Only Historicize,” p. 17).

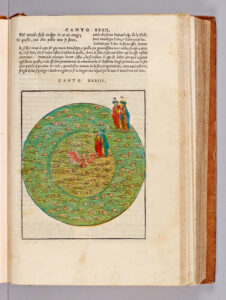

[3] Inferno 33 and the Ugolino episode are steeped in history: in the people and events that shaped Ugolino’s politics. A central node of Pisan politics (and therefore of Ugolino’s politics) was the island of Sardinia, a Pisan possession. I rehearse some of the elements of Ugolino’s Sardinian politics in The Undivine Comedy, connecting Inferno 33 to the Sardinian grafters in Inferno 22 (for whom, see the Commento on Inferno 22):

Ugolino was the Sardinian vicar of Re Enzo, son of Frederic II; Ugolino’s son Guelfo married Elena, Enzo’s daughter, and Ugolino’s grandchildren inherited Enzo’s Sardinian possessions. Ugolino’s son-in-law, Giovanni Visconti, was also a power on the island as judge of Gallura, as was Giovanni’s son, Ugolino’s grandson, Nino Visconti, whom Dante hails in the valley of the princes by his Sardinian title: “giudice Nin” (Purg. 8.53). These connections begin to manifest themselves in Inferno 33 when Ugolino says that Ruggieri appeared to him, in his dream, as “maestro e donno” (Inf. 33.28]): donno is a Sardinianism that occurs only here and in Inferno 22, where it is used in the description of the Sardinian barraters. One is friar Gomita of Gallura (“frate Gomita, / quel di Gallura” [Inf. 22.81-2]), vicar of Nino Visconti, the lord or donno whose enemies he freed for money. The other is “donno Michel Zanche / di Logodoro” (Inf. 22.88-9), a Sardinian noble who originally sided with Genova rather than Pisa; he was killed by his Genovese son-in-law Branca Doria, either out of greed for his Sardinian holdings or because of his later leanings toward Pisa. Sardinia as a catalyst of greed figures in all these dramas, and indeed frate Gomita, betrayer of Nino Visconti, and Michel Zanche, betrayed by Branca Doria, talk of Sardinia in the bolgia of barratry: “e a dir di Sardigna / le lingue lor non si sentono stanche” (in talking of Sardinia their tongues do not grow weary [Inf. 22.89-90]). Sardinia unites all these sinners as the object of their greed and strife, and Ugolino was as rapacious a player (not for nothing does he see himself as a wolf in his dream) as the others. (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 96-7)

[4] The Guelph Visconti and Ghibelline Gherardesca families, traditionally opposed, became allies to protect their Sardinian holdings. Their alliance led to the ill-fated shared magistracy of Ugolino and his grandson Nino Visconti, the same Nino whom Dante hails as a personal friend in Purgatory’s Valley of Princes, calling him by his Sardinian title “giudice Nin gentil” (Purg. 8.53; Nino’s title is “giudice” because the provinces of Sardinia were called “giudicati”).

[5] Ugolino’s career was marked by continuous switching back and forth of party allegiance. Originally Ghibelline, Ugolino was exiled from Ghibelline Pisa in 1275. He returned with the help of Florentine Guelphs. In 1284 he became podestà of Pisa. To protect Pisa from Guelph threats he negotiated with Florence and Lucca and ceded three castles to them, an incident that Dante notes in ambiguous fashion:

Che se ’l conte Ugolino aveva voce d’aver tradita te de le castella, non dovei tu i figliuoi porre a tal croce. (Inf. 33.85-7)

For if Count Ugolino was reputed to have betrayed your fortresses, there was no need to have his sons endure such torment.

[6] In 1285 Ugolino’s grandson, Guelph Nino Visconti, was called to share the office of chief magistrate with his Ghibelline grandfather. However, as well summarized by Guy Raffa, Ugolino apparently “connived with the Pisan Ghibellines, led by the Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini; Ugolino agreed to Ghibelline demands that his grandson Nino be driven from the city, an order that was carried out — with Ugolino purposefully absent from the city — in 1288”. The Archbishop then turned on his co-conspirator: “upon Ugolino’s return to Pisa, Ruggieri incited the public against him (by cleverly exploiting Ugolino’s previous ‘betrayal of the castles’) and had the count — along with two sons (Gaddo and Uguiccione) and two grandsons (Anselmo and Brigata) — arrested and imprisoned”(http://danteworlds.laits.utexas.edu/circle9.html#ugolino).

[7] We cannot be entirely sure which particular perfidious action Dante has in mind. Nassime Chida, the author of “Kinship and Local Power in Dante’s Inferno” (Columbia U. dissertation, 2019), and an expert on the historical circumstances that inform the Inferno (see Chida’s Digital Dante tabulation of divergences between leading biographers of Dante) has studied Ugolino and reviewed all the historical literature. She elegantly clarifies the murkiness of the situation:

The sin that puts Ugolino in Antenora is not specified by Dante; this may or may not be because his sin was obvious to contemporary readers, for the early commentators do not all agree on what the sin might be. Ugolino was more of a diplomat than a warrior and his achievements can easily be construed as betrayals: for example the ceding of the castles, a gesture designed to break the alliance between Pisa’s enemies, was in fact a successful act of diplomacy. In other cases, his “betrayal” may seem much more obvious to modern readers if not contemporaries, for example when he went to war against the city of Pisa as head of a group of noble “fuoriusciti” and won (like Farinata). Finally: would his “conversion” to the parte guelfa be considered a political betrayal? It is not clear.

According to all the historical accounts I have read, including relatively recent research (Il conte Ugolino della Gherardesca tra antropologia e storia, ed. Francesco Mallegni and Maria Luisa Lemut, Pisa 2003), Ugolino cannot be said to have “led” the Pisan forces, although he did participate in the battle. However he was later and often blamed for the defeat, considered to be the start of Pisa’s permanent decline. Furthermore, Ugolino was elected because of this defeat, not in spite of it, precisely because the election of a known Guelph would appease Pisa’s Guelph enemies and provide a suitable interlocutor with whom they could negotiate the terms of peace.

There was a rift between Ugolino and Nino, because supporters of the Gherardesca faction and the Visconti faction seem to have come to blows. However, the reasons for the rift, to my knowledge, cannot be established for sure since we lack the testimony of the parties involved. It could be because of the ceded castles, but it could also be because of the failed negotiations involving the return of Pisa’s prisoners of war, held captive in Genoa, who happened to include Ugolino’s eldest son. As for his responsibility for Nino’s expulsion from the city, while all the historians I have read do suspect it, and such an expulsion would have been difficult or impossible without Ugolino’s complicity, the details are also difficult to confirm. Nino Visconti in any case did not hold it against Ugolino, whom he tried unsuccessfully to rescue after his downfall. The toppling of the regime of the due signori (Ugolino and Nino) was a Ghibelline coup and it involved the manipulation of the Pisan crowds. (Nassime Chida, email to Teodolinda Barolini, dated 11/16/2015)

[8] Chiavacci Leonardi writes that Ugolino’s true betrayal — from Dante’s perspective — was not the ceding of the castles but more likely his betrayal of his grandson, Nino Visconti: “Ma il vero tradimento per cui egli sta nell’ultimo cerchio non sembra poter essere questo, se era solo una voce. Si tratta più probabilmente del suo improvviso voltafaccia quando era signore della città, per cui tradì Nino Visconti accordandosi con l’arcivescovo Ubaldini, secondo una versione da Dante seguita” (The true betrayal committed by Ugolino, for which he is placed in the lowest circle, is most likely not this [the ceding of the castles], given that this was only a rumor. Most likely it was his sudden about-turn when, as lord of the city, he betrayed Nino Visconti and allied himself with Archbishop Ubaldini, according to the version of events that Dante followed [Chiavacci Leonardi commentary to Inferno 33, v. 86, my trans.]).

[9] I agree that the behavior likely of greatest interest to Dante is Ugolino’s treatment of his grandson Nino Visconti, during the period in which the two men shared power in Pisa. There are two features of Dante’s account that are unambiguous and that I believe are linked. One is the importance of Ugolino’s children in Dante’s telling. (They are two sons, Gaddo and Uguiccione, and two grandsons, Anselmo and Brigata, but Dante’s Ugolino refers to them collectively and repeatedly as “figliuoli”, “sons”.) The other is the unexpected presence of Nino Visconti in Purgatorio 8 and the great affection that Dante displays for Nino (an affection for which we have no independent verification). Dante’s concerns in this story center on love and affection: on the nature of the ties that bind us as family members and as friends. Family members should never be reduced to political players and political pawns.

[10] In Dante’s view, Ugolino used and abused his family members in securing and consolidating power over Pisa. However murky the politics and history of the Ugolino episode, the story as Dante tells it is devastatingly clear: it portrays the exploitation of family bonds for political ends. This form of exploitation, while taken to the extreme in Ugolino’s case, was systemic in Dante’s society. Such exploitation is built into the dynastic model: family members are expressions of power to be leveraged for the maintenance and survival of the dynasty.

[11] The Inferno is full of dynastic families, discussed as a historical phenomenon in the Commento on Inferno 5, Inferno 12, and Inferno 27. We saw the exploitation of women for dynastic purposes in Inferno 5: Francesca da Polenta was married to Gianciotto Malatesta as a dynastic pawn, for the mutual advantage of the ruling Polenta family of Ravenna and the ruling Malatesta family of Rimini. In Inferno 33 Dante is again reminding us that all members of a powerful family are exploitable, including children, and that all family members, including children, will suffer.

[12] Technically, Antenora is reserved for political traitors while Caina is for traitors of family, but Dante’s point is that the boundary between the two types of betrayal is blurred. The story of Ugolino and his “figliuoli”, like that of Francesca da Rimini, indicts dynastic politics for not distinguishing between the political unit and the family unit.

* * *

[13] Dante’s account of Ugolino della Gherardesca dramatizes the subordination of love to power. In this encounter with the last great charismatic sinner of Inferno, as with the first, we come back to love, albeit paternal rather than romantic. As occurs in Inferno 5, which moves from its topic (love) to its meta-topic (reading and writing about love), so also Inferno 33 moves from its topic, the family/power nexus, to the meta-topic that Dante proposes: our responsibility as humans to use language to console. We have an obligation to comfort each other with words. Specifically, in this instance a father has a moral obligation to comfort his children, who are dying in inexpressibly grim circumstances.

[14] At stake for Dante in the story of the deaths of Ugolino and his figliuoli is the absence of the paternal word: the father’s failure to speak. The Ugolino episode is an in malo expression of the following principle, passionately held by the author of the Commedia: we have an obligation to speak our love and solidarity, a sacred responsibility to use our human birthright of language to sustain, guide, help and console each other. Language used to comfort and console is a major theme of the Commedia, discussed in the Commento on Inferno 2, “Beatrix loquax and Consolation”. In order to aid Dante, Beatrice is compelled, by love, to speak: “Amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (Love prompted me, that Love which makes me speak [Inf. 2.72]). Ugolino is the opposite: he is not compelled by love, he does not speak. For further discussion of language and consolation, see my essay “A Philosophy of Consolation: The Place of the Other in Life’s Transactions”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

[15] Before discussing Ugolino’s responsibility to his children, we must stipulate that there is good reason for the long tradition of sympathy for Ugolino as father, a tradition to which the commentary tradition eloquently testifies. It is difficult to sit in judgment upon Ugolino, for he is not exaggerating when he tells the pilgrim that no one can know how cruel his death was:

però quel che non puoi avere inteso, cioè come la morte mia fu cruda, udirai, e saprai s’e’ m’ha offeso. (Inf.33.19-21)

however, that which you cannot have heard — that is, the cruel death devised for me — you now shall hear and know if he has wronged me.

[16] Ugolino narrates to Dante the tortured days of imprisonment in the tower and his death by starvation, a death that takes him only after he has witnessed the deaths by starvation one by one of the children and grandchildren. Faced with such a story (the only story in Inferno that focuses at great length on the manner of death), a certain moral pudor on the part of the reader seems advisable; after all, we have not experienced such circumstances. But the rules of Dante’s parlor game involve responding to what we learn, in imitation of the pilgrim. In this case, the pilgrim responds with silence to Ugolino — as Ugolino responded with silence to his children. Dante models the “correct” response to Ugolino, showing the Count no sympathy and leaving him without a word.

[17] In Dante’s view, humans are gifted by their maker with reason and hence with the ability to create language. (There are, of course, some stumbles along the way: see the story of the Tower of Babel, discussed in the Commento on Inferno 31.) In this scheme of things, language is our fundamental privilege and our fundamental responsibility. As Dante feels obliged to seek heroically to use language to describe the indescribable in the exordium of Inferno 32, so Ugolino was — in Dante’s view — obliged to seek heroically to use language to console the inconsolable.

[18] Instead, Ugolino’s heart turns to stone — “sì dentro impetrai” (within, I turned to stone [Inf. 33.49]) — and his tongue dries up, as Dante fears his own tongue will do when he first addresses him (Inf. 32.139). The verb impetrare, to turn to stone, echoes the rima petrosa that informs Inferno 32, signalling again that the cold and love-denying ethos of the petrose prevails. Ugolino’s children weep, but the father does not weep; Ugolino’s sons query him, but the father does not answer.

[19] How talkative Ugolino is now, to the pilgrim, how willing to communicate his point of view and his sense of his own pain, and how he failed utterly to offer a word of consolation to his dying children! Dante revises the historical record, making Ugolino’s grown sons and grandsons into children at the time of imprisonment, thus generating pathos and underscoring the stony-heartedness of the father. The children offer more comfort to the father — they speak more words to him — than the father does to them.

[20] Ugolino’s discourse to Dante is polished, rhetorically well structured, and deeply manipulative, as Bàrberi Squarotti showed in his classic essay “L’orazione del conte Ugolino” (cited in Coordinated Reading). I find most chilling the logical connectors with which Ugolino suggests that he had no choice but to keep silent: “Perciò non lagrimai né rispuos’ io” (Therefore I shed no tears and did not answer [Inf. 33.52]), and “Queta’mi allor per non farli più tristi” (Then I became silent, so that I not make them more sad [Inf. 33.64]). But why would words make his children more sad? They are humans, not the wolf-cubs of Ugolino’s dream.

[21] Ugolino sees himself in dream as a wolf being hunted with its cubs: he is ‘‘il lupo’’ with its ‘‘lupicini’’ (Inf. 33.29). The wolf holds a particular place in Dante’s imagination: by characterizing the Count as a wolf, Dante signals that Ugolino is a figure of rapacious greed, in whom hunger for power was paramount. The lupa (she-wolf) of Inferno 1 is a fearsome figure of lack and insatiable cupidigia. As the masculine variant of the lupa, Ugolino is the father who inflicts on his sons fearsome lack: material lack and starvation in the tower, but also spiritual deprivation with respect to language and comfort and consolation.

[22] Ugolino’s speech is geared to the solicitation of pity. He exploits his children as oratorical pawns in his infernal narrative — as in life they were political pawns in his quest for power. He asks Dante a rhetorical question — “e se non piangi, di che pianger suoli?” (and if you don’t weep now, when would you weep? [Inf. 33.42]) — that is in effect an exhortation to weep for him. And yet, by his own telling, he did not weep for or with his children, as he did not reply to the question that “Anselmiuccio mio” addressed to him:

Io non piangëa, sì dentro impetrai: piangevan elli; e Anselmuccio mio disse: “Tu guardi sì, padre! che hai?”. Perciò non lagrimai ne rispuos’ io ... (Inf. 33.49-52)

I did not weep; within, I turned to stone. They wept; and my poor little Anselm said: ‘Father, you look so . . . What is wrong with you?’ Therefore I shed no tears and did not answer . . .

[23] Ugolino recounts Gaddo’s last words before dying, which are a request for help. He too, like Anselmuccio, speaks in the form of a question, the syntactic unit that requires a reply: “Padre mio, ché non m’aiuti?’” (Father, why do you not help me? [Inf. 33.69]). But Ugolino records no reply. Gaddo’s words hang in space; they receive no answer.

[24] Dante-pilgrim refuses Ugolino’s direct invitation to weep for him. He gives him as response only silence. Dante-narrator, on the other hand, explodes into an apostrophe to Pisa, wishing for Pisa’s destruction and excoriating the city for having tortured the innocent sons, who deserved to be treated with compassion:

Ahi Pisa, vituperio de le genti del bel paese là dove ’l sì suona, poi che i vicini a te punir son lenti, muovasi la Capraia e la Gorgona, e faccian siepe ad Arno in su la foce, sì ch’elli annieghi in te ogne persona! Ché se ’l conte Ugolino aveva voce d’aver tradita te de le castella, non dovei tu i figliuoi porre a tal croce. Innocenti facea l’età novella, novella Tebe, Uguiccione e ’l Brigata e li altri due che ’l canto suso appella. (Inf. 33.79-90)

Ah, Pisa, you the scandal of the peoples of that fair land where sì is heard, because your neighbors are so slow to punish you, may, then, Caprara and Gorgona move and build a hedge across the Arno's mouth, so that it may drown every soul in you! For if Count Ugolino was reputed to have betrayed your fortresses, there was no need to have his sons endure such torment. O Thebes renewed, their years were innocent and young — Brigata, Uguiccione, and the other two my song has named above!

[25] Dante insists on the innocence of youth: “Innocenti facea l’età novella” (their youth made them innocent [Inf. 33.88]). Once again, as in the Geri del Bello episode in Inferno 29, Dante resists violence whose justification is kinship. In Inferno 29 he rejects the logic whereby he himself was obliged to become a killer to avenge the violent death of his cousin Geri del Bello. In Inferno 33 he rejects the logic whereby Ugolino della Gherardesca’s male descendants are killed along with their father. Ugolino’s sins should not have been visited upon his male descendants. Dante counters the logic of tribe and family and insists that youth guarantees innocence. In a society where dynastic politics inevitably leads to the imprisonment and murder of children, this is a radical statement.

[26] Dante will eventually offer the theoretical basis for his position, claiming in Purgatorio 7 that virtue is given by God and does not flow down the branches of a family tree from father to son (Purg. 7.121-23). By the same token that virtue does not pass down genealogically, neither does sin: Guido da Montefeltro is damned (see Inferno 27), while his son Bonconte is saved (see Purgatorio 5). Similarly, Ugolino is damned, while his grandson Nino Visconti is saved.

* * *

[27] After his bitter apostrophe to Pisa, Dante turns his back on Ugolino, and the narrator moves onward. The travelers come to Tolomea, the third zone of Cocytus, reserved for traitors of guests. Here Dante meets Alberigo dei Manfredi, whose family returned from exile to Faenza with the aid of the traitor Tebaldello de’ Zambrasi, another resident of the ninth circle (see Inferno 32, paragraph 22, for Tebaldello’s connection to Gianciotto Malatesta). Alberigo introduces himself as “Frate Alberigo” (118), referring to his status as a frate godente or jovial friar (for the lay order of Frati Godenti, see the hypocrites Catalano and Loderingo, Inferno 23, paragraph 37). Frate Alberigo explains that the souls of Tolomea have a special distinction: they die in the very moment that they commit their heinous act of betrayal, and their bodies, now inhabited by devils, only appear to be still alive on earth. Thus, Dante is amazed that Frate Alberigo (who is thought to have died circa 1307) is already dead: “‘Oh’, diss’ io lui, ‘or se’ tu ancor morto?’” (“But then,” I said, “are you already dead?” [Inf. 33.121]).

[28] The sinners of Tolomea are medieval versions of the modern “zombie”: an undead being created through the animation of a corpse. Dante shows interest in this idea already in Inferno 9, where Virgilio describes the sorceress Erichtho as a maker of animated death: “quella Eritón cruda / che richiamava l’ombre a’ corpi sui” (that savage witch Erichtho, she who called the shades back to their bodies [Inf. 9.23-4]). The theme of animated death governs the last canti of Inferno, and anticipates Dante’s conception of Lucifer.

[29] Frate Alberigo’s language plays up the ambiguous “undead” status of these souls. On the one hand, at the moment of the act of betrayal the soul vacates the body and falls to Hell, and the body is inhabited by a devil (Inf. 33.124-35). On the other, Atropos has not yet pushed the soul away — “innanzi ch’Atropòs mossa le dea” (it has not yet been thrust away by Atropos [126]), cutting the thread of life. Thus the devil takes over the body “until its years have run their course completely”: “mentre che ’l tempo suo tutto sia vòlto” (Inf. 33.132). We infer that the body has a temporal “set-point”, and that the violence of the sin is sufficient to disrupt the fore0rdained life span, a life span that yet cannot be fully deleted.

[30] There are a number of fascinating issues here. With respect to body/soul issues, in this Commentary I have noted Dante’s continual insistence on the unity of body and soul, a unity that holds even when the individual tried to sunder that unity, as in the case of the suicides. My commentary on Inferno 13 is in fact titled “Non-Dualism: Our Bodies, Our Selves”. In elaborating the concept of a zombie, a body on earth that seems alive but is not really alive because the soul is already in Hell, Dante is playing with dualistic elements of popular culture. At the same time, the underlying reality is that these persons are dead, while their bodies “seem alive” on earth: “e in corpo par vivo ancor di sopra” (and up above appears alive, in body [Inf. 33.157]).

[31] Moreover, Dante ventures onto theologically thin ice when he damns folks who have not yet died. He has gone in this dangerous direction before. We noted the flagrant case of Pope Boniface VIII, whose arrival in the bolgia of simony after his death in 1303 is predicted in an encounter with Pope Nicholas III in Inferno 19. There is also the case of Fra Dolcino, the heretic who died in 1307 and whose arrival in the bolgia of the schismatics is predicted by Mohammed in Inferno 28.

[32] In his treatment of Tolomea in Inferno 33, Dante is effectively saying that the gravity of this sin causes the sinner to be damned while still alive, despite a theology of repentance that holds that there is never a day before death when salvation is beyond our grasp. Dante thus has deprived the souls of Tolomea — as he had done to Boniface VIII and Fra Dolcino — of the fundamental “right”, inherent in the theology of repentance, to repent for their sins up to the last moment of life. As I have noted previously in this commentary, Dante here flirts with the very determinism of which Cecco d’Ascoli accused him. See the discussion of Cecco d’Ascoli in the Appendix to Inferno 7 and also the discussion of determinism in the Commento on Inferno 20.

[33] At the end of this canto, the zombie/undead category allows the poet another opportunity to manipulate our suspension of disbelief, offering him yet another way to use the unbelievable to command belief. Frate Alberigo now points to the sinner behind him, and tells Dante that he likely knows him: “Tu ’l dei saper, se tu vien pur mo giuso: / elli è ser Branca Doria” (you must know him, if you’ve just come down; he is Ser Branca Doria [Inf. 33.136-37]). Dante must have known Branca, says Alberigo, given that Dante is a recent arrival in Hell. In fact, we too know of Branca, for Branca is already inscribed into the text of Inferno: Branca Doria is a Genovese nobleman condemned for the murder of his father-in-law, Michele Zanche, a Sardinian whom Dante placed among the grafters in Inferno 22.

[34] At this, the poet stages the bewilderment of the pilgrim, who accuses Frate Alberigo of deceiving him (as per the Geryon principle). The pilgrim is incredulous. Alberigo must be lying, for Branca “eats and drinks and sleeps and puts on clothes”: “‘Io credo’, diss’io lui, ‘che tu m’inganni; / ché Branca Doria non morì unquanche, / e mangia e bee e dorme e veste panni’” (I said to him: “I think that you deceive me, for Branca Doria is not yet dead; he eats and drinks and sleeps and puts on clothes” [Inf. 33.139-41]). Here the stress on the bodily features that normally indicate “life” — Branca after all eats and drinks and sleeps and puts on clothes — underscores the apparent fissure between the body on earth and the soul in Hell. But, in the alternate reality that Dante is inventing, Branca’s body is inhabited by a devil, so it is not in fact alive. Nor, if we think about it, is it “his” body. The dualism is therefore only apparent.

[35] In real reality, the reality of history as compared to Dante’s reality, Branca Doria was indeed still alive. He died in 1325. And, although the theological risk that Dante courts in putting a man in Hell who is not yet dead is the same for Boniface VIII who died in 1303 as for Branca Doria who died in 1325, the notable difference in life spans emphasizes Dante’s audacity. The Inferno, which was not yet written when Boniface was alive, had been circulating for years when Branca Doria died in 1325, four years after Dante’s own death in 1321.

[36] A legend grew up, according to which Branca Doria took revenge on the poet for putting him in Hell while he was still alive by having him beaten (see The Undivine Comedy, p. 297, note 45). The coming into existence of this legend shows that Dante’s early readers were at some level aware of the particular outrageousness — from a theological perspective — of Branca’s case. Reader response generated the legend of the poet’s comeuppance.

[37] The question of truth claims thus comes to the fore. In creating the category of the undead in the final episode of Inferno 33, Dante tropes his master fiction, as I explain in The Undivine Comedy. He offers us dead living people in the place of his customary living dead people: “Dante is here troping his master fiction: instead of living dead people, we now must contend with the idea of dead living people. As the outlines of the fiction become harder to hold onto, we succumb to it more readily, especially when the text reproduces our relation to it within itself” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 94).

[38] In order to counter the pilgrim’s disbelief, Frate Alberigo, the fictional character, appeals to the “reality” of the virtual world that Dante-poet has created: he refers to the contents of Dante’s Inferno. Alberigo describes in detail the bolgia of baratteria in Inferno 22, referring to the Malebranche, Michel Zanche, and the “tenace pece” in which the grafters are immersed:

«Nel fosso sù», diss’el, «de’ Malebranche, là dove bolle la tenace pece, non era ancor giunto Michel Zanche che questi lasciò il diavolo in sua vece nel corpo suo, ed un suo prossimano che ’l tradimento insieme con lui fece. (Inf. 33.142-47)

“There in the Malebranche’s ditch above, where sticky pitch boils up, Michele Zanche had still not come,” he said to me, “when this one — together with a kinsman, who had done the treachery together with him — left a devil in his stead inside his body.”

[39] I analyze this extraordinary truth claim in The Undivine Comedy, noting that “the pilgrim is now in the reader’s position, faced with an unbelievable truth, a ‘ver c’ha faccia di menzogna’ (as earlier, in canto 28’s version of this mirror game, the sinners played the reader’s role)” (p. 94). As we saw, Alberigo persuades the pilgrim to believe him by appealing to “reality”, namely the fiction to which he himself belongs. Alberigo’s reply is one of the most remarkable intratextual moments within the Commedia, as the text buttresses the text, the fiction supports the credibility of the fiction. By way of Alberigo’s references to the text of Inferno 22 — to the Malebranche and to the boiling pitch of the bolgia of baratteria — the pilgrim is convinced.

[40] The poet, who has mirrored and thereby mounted a sneak attack on the reader’s reluctance to believe, concludes Inferno 33 by stating as simple fact what he learned from Frate Alberigo. In this place, says the poet, he found — “trovai” (I found [Inf. 33.155) — a spirit whose soul was in Cocytus, while his body was on earth. The last verse of Inferno 33 repeats as fact the canto’s most startling assertion. There are souls in Hell whose bodies appear alive on earth: “e in corpo par vivo ancor di sopra” (and up above appears alive, in body [Inf. 33.157]).

[41] We see Dante’s willingness to embrace theologically unorthodox concepts that derive from popular culture — here the concept of the undead — bending those concepts to his needs: the idea of animate death is fundamental to Dante’s vision of Hell’s lowest pit, to his vision of Lucifer. He simultaneously uses these concepts to manage our suspension of disbelief in the service of his virtual reality.

Return to top

Return to top