- Although the sixth circle theoretically contains heretics of all stripes, Dante in effect dwells on one type of heresy: Epicureanism, named after the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus

- In Convivio 4.6.11-12, Dante discusses the school of Epicurus in positive terms, on par with the classical philosophical schools of the Stoics and Peripatetics

- In the Commedia, Dante focuses instead on the way in which Epicurus’ materialist philosophy runs counter to Christianity, pointing to the Epicurean belief that the soul dies with the body: “l’anima col corpo morta fanno” (Inf. 10.15)

- Rejection of belief in the immortality of the soul, and thus rejection of belief in the afterlife, constitutes a radical rejection of Christianity

- Effectively, from a Christian perspective, Epicureans are non-believers (what we moderns call atheists)

- Boccaccio makes very clear that to be Epicurean equates to being a non-believer, writing that Guido Cavalcanti held Epicurean positions, and that therefore it was said that he was seeking to show that God did not exist: “e per ciò che egli alquanto tenea della oppinione degli epicuri, si diceva tralla gente volgare che queste sue speculazioni erano solo in cercare se trovar si potesse che Iddio non fosse” (And since he tended to subscribe to the ideas of the Epicureans, it was said among the common herd that these speculations of his were exclusively concerned with whether it could be shown that God did not exist [Dec. 6.9.9])

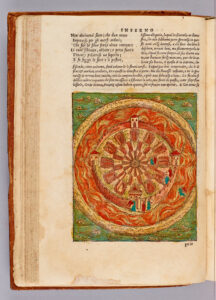

- The contrapasso for heresy — burial within fiery tombs in the city of Dis — reflects the heretics’ willful self-separation of the soul from God: the contrapasso is a troping of death itself, suggesting that somehow these souls are ”more dead” than the other dead souls

- Heresy as willful self-separation of the soul from God is performed in Inferno 10 as dialogue that is not dialogic: language is weaponized to inflict hurt

- In the case of the Epicureans, Dante dramatizes their materialism, showing that the souls whom he meets are eternally enmeshed in the transitory, the ephemeral, the present

- Both souls whom Dante encounters are Florentines and each speaks to one of Dante’s own abiding earthly passions: one speaks of Florentine politics (Farinata degli Uberti) and the other, by referencing his son Guido Cavalcanti, of poets and intellectualism (Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti)

- History: the Florentine magnate families were excluded from governance by the Ordinamenti di Giustizia of 1293; both the Uberti and Cavalcanti are magnate families (see the historians Lansing and Faini, cited in Coordinated Reading)

- Friendship and Poetry: Dante’s friendship with the poet Guido Cavalcanti is recalled through the encounter with Guido’s father, but should not be taken as proof that Dante pre-damned his friend to the same circle of Hell as his father

- Dante’s friendship with Guido Cavalcanti is intertwined in the Commedia with his friendship with another magnate, Forese Donati: the scene between Dante and Cavalcanti’s father among the graves in Inferno 10 echoes Forese’s sonnet to Dante, L’altra notte, where he claims to have seen Dante’s father in a cemetery (see my essay “Amicus eius” in Coordinated Reading)

- The (painful) presence of love in Hell and the link between love and sin, which is fully articulated in Purgatorio 17, the canto where Dante discusses love as the origin of all human behavior, whether good or bad (see “Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell” in Coordinated Reading)

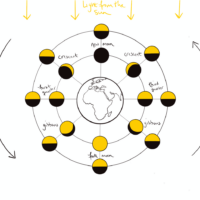

[1] After Dante and Virgilio enter the city of Dis, in verse 106 of Inferno 9, they find a landscape of cemeteries. The tombs are open — the covers are removed — and they are engulfed by flames. Dante asks who are the souls “buried within those sarcophagi”: “seppelite dentro da quell’arche” (Inf. 9.125). The answer is that here may be found heretics, indeed the founders of heresies (“eresiarche”), with their followers from every sect: “Qui son li eresiarche / con lor seguaci, d’ogne setta (Here are arch-heretics / and those who followed them, from every sect [Inf. 9.127-129]).

[2] The contrapasso of the heretics, whose souls are “buried within those sarcophagi” — “seppelite dentro da quell’arche” (Inf. 9.125) — thus involves a troping of death. Their entombment within the kingdom of the dead suggests that they are in some way “more dead” than the other dead and damned souls. In Hell they are buried in tombs that signify their willful turning away from the life of Christian truth to the death of disbelief.

[3] The definition of heresy in the Catechism of the Catholic Church reads:

Heresy is the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth which must be believed with divine and catholic faith, or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same; apostasy is the total repudiation of the Christian faith; schism is the refusal of submission to the Roman Pontiff or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him. (CCC 2089, accessed 9/29/15; the Catechism is a quotation from the Code of Canon Law, canon 751)

[4] Dante tells us that there are many kinds of heretics entombed in the sixth circle. He supports this claim by having the travelers pass the tomb of Pope Anastasius II at the beginning of Inferno 11 (Inf. 11.6-9). Following a medieval tradition based on Gratian’s Decretum and the Liber pontificalis, Dante believed that Pope Anastasius embraced a monophysite heresy, one connected to Acacius, patriarch of Constantinople. This heresy attributed to Christ only a human nature, denying Christ’s divine nature. Dante will return to the issue of heretical belief regarding Christ’s two natures in Paradiso 6, where he focuses on the opposite error: the Emperor Justinian says that he was converted by Pope Agapetus I from the heretical belief that Christ possessed only a divine nature (Par. 6.13-21).

[5] The mystery of Christ’s two natures is a recurring theme throughout the Commedia: it is treated both in malo (for Dante’s consideration of the duality of Christ in malo see Commento on Inferno 25), and in bono (for Dante’s consideration of the duality of Christ in bono, see Purgatorio 31, verses 121-126, and Paradiso, passim).

[6] Through the reference to Pope Anastasius in Inferno 11, Dante indicates that there are many types of heretics housed in the city of Dis. However, in Inferno 10 he focuses almost exclusively on Epicureans. In this canto, Dante stages encounters with two Epicureans, not with souls of any other heretical sect.

[7] Although Dante takes care to indicate that there are many types of heretics housed in the city of Dis, in Inferno 10 he focuses almost exclusively on one group: Epicureans. At the beginning of the canto the travelers find themselves in the part of the cemetery that houses “Epicurus and all his followers”, defined immediately as those who believe that the soul dies with the body:

Suo cimitero da questa parte hanno con Epicuro tutti suoi seguaci, che l’anima col corpo morta fanno. (Inf. 10.13-15)

Within this region is the cemetery of Epicurus and all his followers, those who say the soul die with the body. (Richard Lansing trans.)

[8] Dante subsequently devotes much of Inferno 10 to staging encounters with two Epicurean souls who inhabit one tomb and who are Florentines of the previous generation: one is Farinata degli Uberti, the great Ghibelline leader in the battle of Montaperti, who died the year before Dante’s birth (1212-1264); the other is Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti (1220-1280), the father of Dante’s dear friend, Guido Cavalcanti. To add to the density of this canto, each featured soul speaks to one of Dante’s own abiding passions: one speaks of Florentine politics and the other, by way of his son Guido Cavalcanti, of poets and intellectualism. For Dante, these encounters thus stage his own materialist attachment to both his place of origin and his poetic project.

[9] Epicurus was a Greek philosopher of classical antiquity (341–270 B.C.E.), whose materialist philosophy Dante treats respectfully in his philosophical treatise Convivio (written circa 1304-1307), on a par with his treatment in the same treatise of the classical philosophical schools of Peripatetics and Stoics (see Convivio 4.6.11-12). However, in Inferno 10 Dante positions himself vis-à-vis Epicureanism differently than he had in the Convivio, by zeroing in on Epicurus’ denial of the immortality of the soul and defining Epicureans as “those who say the soul dies with the body”: “che l’anima col corpo morta fanno” (Inf. 10.15).[1]

[10] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains the philosopher’s commitment to “a radical materialism which dispensed with transcendent entities such as the Platonic Ideas or Forms” and his desire to “disprove the possibility of the soul’s survival after death, and hence the prospect of punishment in the afterlife”:

Epicurus believed that, on the basis of a radical materialism which dispensed with transcendent entities such as the Platonic Ideas or Forms, he could disprove the possibility of the soul’s survival after death, and hence the prospect of punishment in the afterlife. He regarded the unacknowledged fear of death and punishment as the primary cause of anxiety among human beings, and anxiety in turn as the source of extreme and irrational desires. The elimination of the fears and corresponding desires would leave people free to pursue the pleasures, both physical and mental, to which they are naturally drawn, and to enjoy the peace of mind that is consequent upon their regularly expected and achieved satisfaction. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epicurus/)

[11] The belief that the soul is material and dies with the body is not compatible with Christianity, a religion that holds to the immortality of the soul and to the concept of an eternal afterlife. A contemporary gloss of “Epicurean” as Dante uses it in Inferno 10 is provided by Boccaccio in the Decameron, in a story about the poet Guido Cavalcanti, whose father is among Dante’s Epicureans. Writing in the wake of Inferno 10, Boccaccio makes very clear that to be Epicurean equates to being a non-believer, what we moderns call atheists. He explains that Guido Cavalcanti held Epicurean positions, and that therefore the vulgar folk said that he was seeking to show that God did not exist:

. . . Guido alcuna volta speculando molto abstratto dagli uomini divenia; e per ciò che egli alquanto tenea della oppinione degli epicuri, si diceva tralla gente volgare che queste sue speculazioni erano solo in cercare se trovar si potesse che Iddio non fosse. (Decameron, 6.9.9)

Guido, given to speculation, would become much abstracted from men; and since he was somewhat inclined to the opinion of the Epicureans, the vulgar averred that these speculations of his had no other scope than to prove that God did not exist.

[12] Why does Dante choose to focus on Epicureanism in his circle of heresy? In my view, Dante’s choice of Epicureanism is part of an overall strategy regarding classical antiquity in the Commedia.

[13] Throughout the poem Dante treats classical antiquity in a way that both celebrates it and acknowledges its limitations with respect to Christianity, finding ways thereby to build a palpable tension into the fabric of his poem (see Dante’s Poets, chapter 3). Similarly, he balances Christian with classical examples, to various ends; thus, throughout Malebolge, the circle of fraud, this commentary will note his deployment of classical and contemporary couples, the most famous such duo being Ulysses and Guido da Montefeltro (see The Undivine Comedy, chapter 4).

[14] Moreover, and this is my point with respect to the interpretation of Inferno 10, Dante sometimes uses classical antiquity as a foil to sidestep and defuse particularly difficult issues, issues that are politically dangerous.

[15] To be clear, Dante does not always use classical antiquity as a way to sidestep contemporary hot-button issues; for instance, he is scathing with respect to the corruption of the Church and in Inferno 19 he does not draw back from letting us know that Pope Boniface VIII will join the simoniacs in the third bolgia of the circle of fraud.

[16] But in his treatment of the fourth bolgia of the circle of fraud, the bolgia devoted to false prophets, diviners, astrologers and the like, Dante does use classical seers and diviners in order to sidestep the burning and politically dangerous issue of Christian astrologers. Indeed, this is precisely the thesis that I put forward in my reading of Inferno 20 in this Commento.

[17] I suggest that we find a strategy deployed in Inferno 10 that is similar to what we find in Inferno 20. In Inferno 10 Dante sidesteps the contemporary heresies that had become politically dangerous in his day. Much as in Inferno 20, where Dante both avoids and references contemporary astrologers ( by putting a brief mention of the notorious Michael Scot and a few others at the end of the canto), in Inferno 10 Dante both avoids and references the heresy that was most obvious to a contemporary Florentine, namely Catharism (in 1283 Farinata, when Dante was 18, Farinata was tried and postumously condemned as a Cathar).

[18] Rather than openly confronting the reality of contemporary heresies in Inferno 10, Dante chooses instead to pursue an oblique and indirect treatment of the topic of heresy, which he does by focusing on the radical materialism of an ancient philosopher and that philosopher’s consequent rejection of the immortality of the soul.

[19] In this way Dante both skirts contemporary politics and addresses an issue of the utmost importance to all Christians, and perhaps particularly to a poet of the afterlife. As the fourteenth-century commentator Benvenuto da Imola noted, if Epicurus were correct, then there would be no hell, purgatory, and paradise:

Epicurei enim negant immortalitatem animae, et per consequens non est dare infernum, nec purgatorium, nec paradisum; quae opinio non solum est contra sacram theologiam, sed etiam contra omnem bonam philosophiam; unde non solum ponit errorem in fide, sed etiam in scientia humana. (Benvenuto da Imola, gloss to verses 13-15)

Epicureans deny the immortality of the soul, and therefore they do not posit hell, or purgatory, or paradise, an opinion that is not only against sacred theology, but also against all good philosophy. Hence Epicureans not only commit an error in their faith, but also with respect to fundamental human knowledge.

[20] Dante addresses the Epicurean rejection of the eternal and transcendent by dramatizing encounters with two souls who remain eternally enmeshed in the transitory and ephemeral. Benvenuto da Imola captures the essence of the materialist heresy that Dante here dramatizes, writing about Farinata that “as an imitator of Epicurus he did not believe that there was another world besides this one, so that in all ways he strove to excel in this brief life, since he did not believe in another better one”: “imitator Epicuri non credebat esse alium mundum nisi istum; unde omnibus modis studebat excellere in ista vita brevi, quia non sperabat aliam meliorem” (Benvenuto, gloss to verses 22-24).

* * *

[21] The narrative structure of Inferno 10 beautifully reflects the enmeshed density of the Epicureans’ excessive attachment to the present. By splicing the dialogues with Farinata and Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti into one another, Dante dramatizes the way that these souls are so caught up in their own selves that they literally do not hear or in any way register each other’s suffering. In effect, in Inferno 10 Dante scripts dialogue that is not dialogic, thus dramatizing the Epicurean rejection of the transcendent as a willful self-separation of the soul from its source of happiness and, as we shall see, of all knowledge.

[22] In Inferno 10, language is weaponized by the narcissistic materialism of the speaker. We have experienced the advent of salvific language in the Commedia (we think of Beatrice’s “Amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” in Inferno 2.72); now we experience language that hurts. Thus, Farinata’s first question to the pilgrim, “Chi fuor li maggior tui?” (Who were your ancestors? [Inf. 10.42]), receives a reply that shows Dante to be a political adversary, and is therefore followed by what Farinata imprudently delivers as though it were a knock-out blow:

Fieramente furo avversi a me e a miei primi e a mia parte, sì che per due fïate li dispersi. (Inf. 10.46-48)

They were ferocious enemies of mine and of my parents and my party, so that I had to scatter them twice over.

[23] But the pilgrim too has weapons at his disposal, and indeed Florentine history, in which the Guelphs ultimately prevailed over the Ghibellines, allows the pilgrim’s rejoinder to deliver an even stronger blow:

“S’ei fur cacciati, ei tornar d’ogne parte”, rispuos’io lui, “l’una e l’altra fïata; ma i vostri non appreser ben quell’arte”. (Inf. 10.49-51)

“If they were driven out”, I answered him, “they still returned both times, from every quarter; but yours were never quick to learn that art”.

[24] The above conversation references four cataclysmic events in Florentine politics of the thirteenth century, as Florence oscillated between Guelph and Ghibelline control until the ultimate defeat of Farinata and the Ghibellines at the battle of Benevento of 1266. In effect the dialogue lays out two sets of factional routs and returns. The first set of rout and return comprises the 1248 defeat of the Guelphs by the Ghibellines, with the help of Emperor Frederic II (who is present among the Epicureans in Inferno 10), followed by the return of the Guelphs in 1251, after the death of the Emperior.

[25] The second set comprises the 1260 defeat of the Guelphs by the Ghibellines at the battle of Montaperti, where Farinata led the Ghibellines to victory with the help of the Sienese and Manfredi, Frederic’s successor, and then the subsequent defeat of the Ghibellines and return of the Guelphs following the battle of Benevento and the death of Manfredi in 1266.

[26] In the verbal skirmish between Farinata and the pilgirm, Dante-poet thus provides the reader of the Commedia a second installment in Florentine politics: while the history lesson of Inferno 6 treated Dante’s own time, this second installment treats historical events that occurred a generation earlier.

[27] The performance of materialism takes a turn from the political to the exquisitely personal in the twenty-one poignant verses (52-72) that make up the encounter between Dante-pilgrim and Cavalcanti de’ Cavalcanti. Cavalcante arises from the tomb and interrupts the bitter factional dialogue between his tomb-mate and the pilgrim, looking about for his son Guido and posing a question about his son’s whereabouts that is grafted onto a tellingly materialist premise.

[28] Presuming — as he should not have done — that Dante is able to take the voyage through the afterlife because of his high intellect, “per altezza d’ingegno” (Inf. 10.59),[2] Cavalcante asks a question that posits an implicit rivalry for intellectual supremacy between his son Guido and Dante, asking:

Se per questo cieco

carcere vai per altezza d’ingegno,

mio figlio ov’è? e perché non è teco?

(Inf. 10.58-60)

If it is your high intellect

that lets you journey here, through this high prison,

where is my son? And why is he not with you?

[29] The personal nature of the question takes an immediate further turn, as the pilgrim disavows that such a journey as his could be undertaken on the basis of one’s own powers. No: as we learned in Inferno 2, such a journey can only be willed by the highest power. And this is the theological burden that informs the pilgrim’s reply, which begins “Da me stesso non vegno” (My own powers have not brought me [Inf. 10.61]). The pilgrim then declares the nature of his journey, pointing to Virgilio as “he who awaits me there leads me through here, perhaps to one your Guido did disdain”: “colui ch’attende là, per qui mi mena / forse cui Guido vostro ebbe a disdegno” (Inf. 10.62-3).

[30] These verses have generated acres of exegesis over the centuries. With respect to the identity of the one whom Guido disdains, I support the reading whereby this is a reference to Beatrice:

[…] the argument as to whether Beatrice or God is intended is a spurious one, since they amount to the same thing; however, in that Dante and Guido share a past as love poets, and Beatrice is that localized version of the divine that Dante chose and Guido refused to discover within love poetry, she would seem the more appropriate choice (Dante’s Poets, 146)

[31] Guido Cavalcanti was, according to the Vita Nuova, Dante’s “first friend”, one with whom he wrote poetry and shared an intellectual life. In conversation with his best friend’s father, Dante here suggests that Guido “disdained” the one to whom Virgilio is leading him (Beatrice), thus pointing to the huge ideological and poetic divergence that arose between the two friends.

[32] This characterization of Guido is not misleading, in the sense that in much of his poetry Guido Cavalcanti did not see objects of love as salvific, as potential “beatrici” (the word “beatrice” literally means “she who beatifies”). With the exception of some of his ballate, Guido embraced a tragic view of love, and therefore the beloved, however noble in herself, is a destructive force.

[33] Adding to the linguistic and dramatic density of the episode, these few verses also offer an extraordinary demonstration of the poet’s ability to use language and syntax performatively. Dante-poet plants the past absolute of the verb avere in verse 63 (“ebbe a disdegno” or “held in disdain”) and then dramatizes the rest of the scene based on Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti misconstruing the use of the passato remoto, taking the tense of the verb as a sign that his son Guido is already dead.

[34] As with Dante and Farinata, the connections that exist between Dante and Cavalcanti senior do nothing to strengthen bonds between the two. Though Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti and Dante share a love for Guido Cavalcanti, Dante-pilgrim ends up grievously hurting the father, by giving him the idea that his beloved son is dead. Of course, Dante-pilgrima had no intention of communicating Guido’s death — Guido’s death had not yet occurred in April 1300 — and in truth Cavalcante almost willfully fixates on the tense of “ebbe”, ignoring everything else that the pilgrim has said.

[35] That willful fixation that allows Cavalcanti senior to infer the worst, a worst that was not even intended, is the core of the materialist heresy, as Dante here presents it.

[36] The intensely poignant interaction between the pilgrim and Cavalcanti senior is completely ignored by Farinata, who resumes speaking to Dante-pilgrim in verse 73 as though his tomb-mate did not exist and as though the conversation between Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti and the pilgrim about his son Guido had not occurred.

[37] Again, the poet uses dialogue that wounds to create performance and dramatic intensity: Farinata begins to speak by repeating verbatim, in slightly different order, the wounding words that the pilgrim last spoke to him, before the appearance of Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti. Thus, the pilgrim’s last words to Farinata, in verse 51, “ma i vostri non appreser ben quell’arte” (but yours were never quick to learn that art), become “‘S’elli han quell’ arte’, disse, ‘male appresa, / ciò mi tormenta più che questo letto’” (“If they were slow,” he said, “to learn that art, / that is more torment to me than this bed” [Inf. 10.77-78]).

[38] In verse 78 Dante-poet bends theology to reinforce our sense of the harm that is inflicted by Dante-pilgrim on Farinata, having Farinata state that his eternal suffering in Hell is increased by what he has learned of his family’s political destiny from his fellow Florentine. In other words, his eternal suffering is increased by what Dante has just now said to him. This claim is of course absurd in theological terms,[3] and gives us another insight into Dante’s unabashed use of dialogue and story-line to heighten the drama of his narrative.

* * *

[39] By the last two decades of the Duecento, a class of very wealthy Florentine nobles with a history of violence were classified as “magnates” and excluded from Florentine governance by the Ordinamenti di Giustizia of 1293. In her book The Florentine Magnates (see Coordinated Reading), the historian Carol Lansing writes thus of the magnates and of the Ordinamenti di Giustizia:

The laws restraining the magnates were a part of this transition to guild rule. The early statutes were an effort to pacify the city by ending the vendettas that led to factional clashes … Who was restricted under the statutes? The guildsmen who wrote the laws apparently knew whom they wanted to include but because of the fluidity of urban society had some difficulty in naming specific criteria for magnate status. The group was called “potentes, nobiles, vel magnates”, powerful men, nobles or magnates. A law of October 1286 defined them as those houses which had included a knight within the past twenty years. (Lansing, The Florentine Magnates, p. 13)

[40] In effect, magnate status was defined by knighthood and a past record of violence, implied by the posting of security (Lansing, The Florentine Magnates, 147). More recently, historian Enrico Faini defines the magnate class in Dante’s time thus:

Per gli uomini dell’età di Dante il nobile non era più il vecchio miles/cittadino, ma il cavaliere addobbato e straricco, il ‘magnate’ così come veniva definito dagli ordinamenti popolari.

For the men of Dante’s age the nobleman was no longer the old citizen-soldier, but an extremely rich and decorated knight, as the “magnate” was defined in the popular ordinances. (“Ruolo sociale e memoria degli Alighieri prima di Dante,” p. 2)

[41] The Cavalcanti and Uberti families are both present in the Appendix of Lansing’s book that lists the Florentine magnate families excluded by the Ordinamenti di Giustizia. On this list we find the names Cavalcanti and Uberti.

[42] When the Ordinamenti di Giustizia were instituted in January 1293, Dante was 27 years old. His family was not excluded by the Ordinamenti, as it did not then possess sufficient wealth or social standing. (See Faini on the backward slide of the Alighieri family fortunes.) Thus, Dante was able to participate in the Florentine government, and indeed went on to serve as a prior, while Guido Cavalcanti was not accorded this privilege.

[43] Decades ago, Mario Marti plausibly suggested that this divergence was a contributing factor in the rift between the two friends (for a discussion of Marti and other views on this issue, see my essay “Amicus eius: Dante and the Semantics of Friendship”, in Coordinated Reading). This thesis was picked up recently by historian Silvia Diacciati:

Quella di Dante fu una svolta “democratica” che l’amico e magnate Guido Cavalcanti, col quale aveva un tempo condiviso la medesima visione aristocratica della cultura, non poté accettare . . . (Diacciati, “Dante: relazioni sociali e vita pubblica,” p. 23)

Dante’s was a “democratic” turn — a turn that his magnate friend Guido Cavalcanti, with whom he had once shared the same aristocratic vision of culture, could not possibly accept . . .

[44] Another magnate friend of Dante’s Florentine youth whose intimacy with Dante is attested in poetry is Forese Donati. The two men exchanged a tenzone of insulting sonnets in the 1290s (see the Commento on Purgatorio 24). Since Forese died in 1296, we know that the sonnet-exchange between Dante and Forese belongs to the decade in which Dante was constructing his Florentine career: as poet, as writer of the Vita Nuova (1293-1294) and best friend of Guido Cavalcanti, as citizen-intellectual, and as politician. In “Amicus eius: Dante and the Semantics of Friendship”, I argue that the Commedia attests to “a kind of psychic bleeding of Dante’s friendship with Forese into his friendship with Cavalcanti and vice versa” (“Amicus eius,” 62).

[45] As an example of the “psychic bleeding of Dante’s friendship with Forese into his friendship with Cavalcanti and vice versa”, I offer the way in which the scene among the graves of Inferno 10 replays one of Forese Donati’s pre-1296 sonnets to Dante, L’altra notte. I suggest that Dante recalls and echoes the early sonnet in his choreography of Inferno 10:

The entire scene of Forese’s L’altra notte, the sighting of the ghost of the father among the graves and the father’s conjuring of the friendship with his son, seems replayed in Inferno 10’s encounter (also among the graves) between a man (now Dante, in place of Forese) and the father of his friend (now Cavalcanti de’ Cavalcanti, in place of Alighiero Bellincione). In other words, Dante in Inferno 10 constructs an encounter between himself and the father of his friend Guido Cavalcanti that in some ways echoes Forese’s imagined encounter with Alighiero in the tenzone. Moreover, the encounter of Inferno 10 is one in which Cavalcanti senior appeals to Dante’s friendship with his son Guido much as Alighiero appeals to Forese’s friendship with his son Dante: “per amor di Dante” in the sonnet L’altra notte has become Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti’s anguished “mio figlio ov’è? e perché non è teco?” ( Inf. 10.60). (“Amicus eius,” pp. 62-63)

[46] The scene in the cemetery of Inferno 10 thus replays the elements of a sonnet impugning Dante’s father, written by the youthful Forese Donati before his death in 1296. This reminiscence underscores the enormous personal stake that Dante has in the materia of Inferno 10.

[47] Let us recapitulate those stakes. Dante is invested in the Farinata encounter through his own service as a prior in the Florentine government. Dante’s time as prior led to his exile, prophesied by Farinata more explicitly than it had been prophesied by Ciacco in Inferno 6. In order to exact payment for Dante’s cutting remark that Farinata’s family will not succeed in returning to Florence, Farinata prophesies that before 50 moons have passed Dante will himself learn how difficult is the “art” of returning to the city: “Ma non cinquanta volte fia raccesa / la faccia de la donna che qui regge, / che tu saprai quanto quell’ arte pesa” (And yet the Lady who is ruler here / will not have her face kindled fifty times / before you learn how heavy is that art [Inf. 10.79-81]). The Inferno’s second installment in Florentine politics is thus a second reference to the pain and dishonor of Dante’s own exile.

[48] Turning to the encounter with Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti, it should be noted that by the time Dante wrote Inferno 10, his intense friendship with Guido Cavalcanti had run its course. The much speculated-on rift between the two (see “Amicus eius”) had occurred. By stating this fact, I do not at all mean to lend my support to the thesis that Dante condemns his friend Guido as Epicurean in this canto. Indeed, it is an interpretive error to make such a straight line between the father and the son, when Dante lets us know repeatedly that he does not condemn sons to follow in the footsteps of their fathers.

[49] We cannot know to what degree Boccaccio’s characterization of Guido as an Epicurean derives from sources other than Inferno 10 that are no longer known to us. It is therefore all the more important for me to articulate clearly the position that I have held since I wrote Dante’s Poets (1984), namely that Dante does not intend to equate Guido with his father, and thus to “pre-condemn” his friend to the circle of heresy:

[…] Dante does not choose to close Guido within the limits of Inferno X, a fact that is stressed immediately in the pilgrim’s last words to Farinata, containing his final message for Cavalcanti senior: “Or direte dunque a quel caduto / che ’1 suo nato è co’ vivi ancor congiunto” (Now tell therefore that fallen one that his son is still among the living [110-111]). These verses, with their emphatic “ancor congiunto”, refer not only to Guido’s literal life, in the spring of 1300, but also to his metaphoric life, a matter on which Dante is deliberately ambivalent, i.e. open. (Dante’s Poets, pp. 147-48)

[50] In Dante’s Lyric Poetry: Poems of Youth and of the ‘Vita Nuova’, I again refute the idea that Inferno 10 is intended to signal Guido’s certain damnation:

I do not subscribe to the view according to which Dante condemns Guido with his father Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti in the tenth canto of the Inferno (even less that he is already thinking about such a condemnation when he wrote Guido, i’ vorrei); I have always maintained that Dante is deliberately ambiguous with regard to the destiny of the friend who, in the fiction of the Commedia, is explicitly “co’ vivi ancor congiunto” (still among the living [Inf. 10.111]). And in any case Dante does not condemn sons for the sins of their fathers: one need only recall the examples — which Dante is at pains to provide us — of Manfredi and Bonconte. (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 120)

[51] Dante goes to great lengths to make clear in the Commedia that the damnation of fathers does not determine the damnation of sons. Thus Bonconte da Montefeltro is saved while his father, Guido da Montefeltro, is damned. At the same time, however, there is no doubt that Dante’s treatment of Guido’s father contaminated the historical reception of the son: “Dante in this sense cast a shadow on Guido’s reputation, linking the name of his friend in perpetuity to hell and damnation in the cultural imaginary” (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 120).

[52] There is, in other words, much that is ambiguous and shaded in Dante’s treatment of Guido Cavalcanti in the Commedia, as I have discussed in many works. In a reading of Inferno 10, it seems most useful to focus on the longue durée, the long history of this intense friendship. In his great poem of perfect and perfectly transparent friendship, Guido, i’ vorrfei che tu e Lapo ed io, the young Dante marshals his friends’ names, first among them Guido’s, as talismans of intimacy:

Guido, i’ vorrei che tu e Lapo ed io, fossimo presi per incantamento e messi in un vasel ch’ad ogni vento per mare andasse al voler vostro e mio; sì che fortuna od altro tempo rio non ci potesse dare impedimento, anzi, vivendo sempre in un talento, di star insieme crescesse il disio. E monna Vanna e monna Lagia poi con quella ch’è sul numer de le trenta con noi ponesse il buono incantatore: e quivi ragionar sempre d’amore, e ciascuna di lor fosse contenta sì come credo che sarémo noi.

Guido, I wish that Lapo, you, and I were carried off by some enchanter’s spell and set upon a ship to sail the sea where every wind would favour our command, so neither thunderstorms nor cloudy skies might ever have the power to hold us back, but rather, cleaving to this single wish, that our desire to live as one would grow. And Lady Vanna were with Lady Lagia borne to us with her who’s number thirty by our good enchanter’s wizardry: to talk of love would be our sole pursui t, and each of them would find herself content, just as I think that we should likewise be. (Richard Lansing trans.)

[53] Into this reverie of ahistorical and dechronologized friendship, pure and untarnished by time and ego and history, by those very contingincies — such as who is a magnate and who is not — that necessarily catalyze our divergent egos and divergent interests and are therefore destined to separate us, what does Inferno 10 do? It drives the wedge of history and contingency and ego.

[54] For, Inferno 10 is, textually, the very opposite of the sonnet Guido, i’ vorrei: the sonnet tells us of love untouched by history; the canto tells us of history that defeats love. Inferno 10 is an account of how history —i n this case the minutely evoked Florentine history of the generation before Dante as well as the effects of the Ordinamenti di Giustizia — must and does tarnish love and friendship.[4]

* * *

[55] Towards the end of Inferno 10, Farinata explains that he can see the future but not the present (Inf. 10.100-08). He sees the future as long as the events are distant, but as events draw more near, they become less and less visible, until finally they disappear altogether: “Quando s’appressano o son, tutto è vano / nostro intelletto (But when events draw near or are, our minds / are useless [Inf. 10.103-4]). Dante here portrays a cognitive eclipse of the sun, whereby the light grows less and less, until finally it is extinguished altogether. Moreover, we have to wonder: if an event was known before it happened, but ceases to be known when it occurs, was it ever in fact known at all? As Farinata says: “nulla sapem di vostro stato umano” (we know nothing of your human state [Inf. 10.105]).

[56] Hence these materialists, who believed only in the present and in what they could see and touch and love in the present, are now cut off from the present altogether. With this trope of souls who are cut off from knowledge of the present (it has been debated whether this information refers only to souls in the circle of heresy or to all souls in hell; I will not here step into this debate, except to note that it matters that this information is given in Inferno 10, rather than elsewhere) Dante makes another point about heresy. He separates from knowledge those who thought they knew everything worth knowing. Adding to the trope of burial in flaming sepulchres, Dante again figures heresy as willful self-separation from truth, knowledge, and life.

[57] Dante depicts the heresy of Epicureanism as a materialist and futile and eternal attachment to the present, with all its conflict and pain preserved. He shows the pain caused by excessive attachment — excessive love for things of earth (in other words, for those goods that theologians call “secondary goods”) — in both the interaction with Farinata and the interaction with Cavalcanti senior. Most expressive of this pain to me are Cavalcanti’s desperate questions “mio figlio ov’ è? e perché non è teco?” (“Where is my son? Why is he not with you?” [Inf. 10.60]).

[58] These questions embody the pain that Dante sees in a life on earth devoted only to life on earth, as expressed in more recent times by the materialist hero of the novel Il Gattopardo: “ma al di là di quanto possiamo sperare di accarezzare con queste mani non abbiamo obblighi” (But beyond what we can hope to caress with these hands we have no obligations [Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, Il Gattopardo, ch. 1]).

[59] There is a special pathos in Inferno 10, because in it Dante constrains us to consider the link between sin and love.

[60] In this way Inferno 10 connects to the revelation that Dante will make much later, in Purgatorio 17, where he tells us that all human behavior, whether good or bad, has its origin in love. The great speech of Purgatorio 17 on love as the origin of all that humans do has not been discussed by Dante scholars with respect to Dante’s Hell, but it should be: in the palpable love of the sinners of Inferno 10, in the palpable presence of love that is still recognizable as love, Dante dramatizes the law that he eventually sets forth in Purgatorio 17.

[61] As I argued in “Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell”, the mystery at the heart of Inferno 10, the mystery that generates its enormous poetic power, is the connection of love to sin:

What gives Inferno 10 its special grip on the reader is that the love of Cavalcante and Farinata is still recognizable as love. While the original love of most sinners in hell is perverted and distorted beyond recognition, in Dante’s treatment of the heretics we can still individuate the conversio toward a secondary good that Aquinas delineates as sin. And when that secondary good is a beloved child, whose well-being the father still craves, the impact on us as human beings is very great, since the canto forces us to consider how emotions in which we all share can ultimately become reified and sinful. (“Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell,” 2000, rpt. in Dante and the Origins of Italian Literary Culture, 120)

[1] Let me take this opportunity to note that this canto offers an installment in Dante’s ongoing meditation on the body/soul nexus. The body/soul meditation is effectively never absent from the Commedia, given the embodied status of the pilgrim (see Inferno 1-2). At the same time, the body/soul meditation reaches moments of particular intensity in Inferno 13 and Inferno 25.

[2] This part of the encounter with Guido’s father also suggests that Dante’s own extraordinary gifts were perceived early in his life, by members of the preceding generation (Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti died circa 1280). I discuss this aspect of Dante’s interaction with the preceding generation in my commentary to Inferno 15, where the pilgrim encounters Brunetto Latini.

[3] This idea is an import from the love lyric, in which there existed the convention of aferlife hyperbole, usually functioning in reverse: for instance, in the canzone Lo doloroso amor, Dante declares that his soul will be so intent on imagining his lady that it will be immunized from the pains of hell (Lo doloroso amor, 38–40).

[4] To be clear, the separation of these friends is a feature of the written record long before Inferno 10; see “Amicus eius” for a full account.

Return to top

Return to top