Purgatorio 14 begins dramatically, with an interrogative in direct discourse, as one spirit queries another. Later in the canto we learn the names of these spirits; they are Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli. They are wondering about the identity of the man who has come among them while still alive:

«Chi è costui che ’l nostro monte cerchia prima che morte li abbia dato il volo, e apre li occhi a sua voglia e coverchia?». (Purg. 14.1-3)

“Who is this man who, although death has yet to grant him flight, can circle round our mountain, and can, at will, open and shut his eyes?”

This opening “Chi è costui?” — “Who is this man?” — continues the theme of names and the withholding of names that we have been tracing since Purgatorio 11’s mystery poet who will chase the first and second Guido from the nest, the unnamed name at the core of the terrace of pride: “e forse è nato / che l’uno e l’altro caccerà dal nido” (and he perhaps is born who will chase both out of the nest [Purg. 11.98-99]). We recall that Oderisi told the pilgrim that all nominanza — glory, but literally the recognition that accrues to one’s name — is fleeting like the color of grass: “La vostra nominanza è color d’erba, / che viene e va” (Your glory wears the color of the grass that comes and goes [Purg. 11.115-16]). And now Dante declines to give his name to his interlocutors, because, he says, he is not yet famous enough! The pilgrim says:

dirvi ch’i’ sia, saria parlare indarno, ché ’l nome mio ancor molto non suona. (Purg. 14.20-21)

to tell you who I am would be to speak in vain — my name has not yet gained much fame.

Without saying his name, Dante indicates that he comes from the valley of the river Arno. The name of the Arno river is also at first withheld, like Dante’s own: described as a “fiumicel” (little river [Purg. 14.17]), and then ostentatiously intuited by one of the souls in verse 24, “Arno” is finally labeled a name that should perish in verse 30. The mention of the Arno river and its valley triggers a meditation on the corrupted cities that are situated along the Arno’s banks.

This is an account of human “decadence”: the inhabitants of each city situated on the shores of the Arno as it flows from the mountains to the sea are presented as beasts. The Arno flows from the mountains of the Casentino region in the Appenines down, down down . . . until it empties into the sea at Pisa. In Dante’s telling, as the river falls, so do the inhabitants of the cities that line its banks become more degraded. Thus, the river begins among foul hogs in the mountains, and then descends to the snarling curs of Arezzo; the curs become wolves when the Arno reaches Florence, and ultimately, when the river comes to the end of its fall, the wolves are foxes, in Pisa.

Dante subscribed to a worldview current through the Renaissance, whereby there is a hierarchy of created beings that places humans in between angels (above) and beasts (below). Therefore, from a fourteenth-century perspective, to describe humans as beasts is to describe humans who have literally “fallen” — “decadence” derives from the verb cadere, to fall — from their prescribed place in the order of being.

Dante highlights the idea of a “falling” in his dramatic presentation of the corrupt valley of the Arno: the phrases “venendo giuso” (coming downward [Purg. 14.46]), “Vassi caggendo” ([it goes on falling [Purg. 14.49]), and “Discesa poi” (having thus descended [Purg. 14.52]) are all markers of the river’s falling flow. This passage is reminiscent of another evocative description of human decadence, found in the parallel canto 14 of Inferno: namely, the statue of the Old Man of Crete.

The speaker in Purgatorio 14’s discourse on the Arno, Guido del Duca, moves into a prophetic mode, speaking of the future brutalities that will be committed against the Florentines by the nephew of his purgatorial companion, Rinieri da Calboli. Rinieri’s nephew is Fulcieri da Calboli. As podestà (chief magistrate) of Florence in 1303, Fulcieri da Calboli carried out persecutions against the enemies of the Blacks, who were newly come to power.

As a White, Dante was exiled in consequence of this same Black takeover; in fact, in this passage, Dante is speaking about the time that immediately succeeds his own exile in 1302. As the Bosco-Reggio commentary points out, Fulcieri da Calboli became podestà in Florence right after the magistrate who signed Dante’s own condemnation, whose name is Cante de’ Gabrielli da Gubbio.

Guido del Duca’s meditation moves from Tuscany to his home region of Romagna, and from a fiery prophetic mode into an elegiac mode, as he conjures the great noble casati of Romagna that have decayed or have disappeared. Notable in this section is the melancholy with which Guido del Duca conjures not just families that have withered, but families in which cortesia and onore no longer hold sway. The cortesia of past times brings out a nostalgic melancholy in Dante, but also the analytic insistence that virtue is not often passed on from parent to child. This is the theme of heredity, first raised in the Valley of the Princes (Purgatorio 8), whose inhabitants frequently embody Dante’s thesis that the courtly values of old are not sustained.

Here, on the terrace of envy, Guido del Duca is able to point to his comrade, Rinieri da Calboli, whose nephew disgraces himself through his butchery in Florence: “molti di vita e sé di pregio priva” (depriving many of life, himself of honor [Purg. 14.63]). Fulcieri da Calboli deprives others of life (he kills them, butcher that he is), but he deprives himself of honor: “sé di pregio priva”. The word here is “pregio”, derived from Occitan pretz. This is the honor that instead the Malaspina family still possesses, given that they are continue to be ornamented by pretz: “del pregio de la borsa e de la spada” (the glory of the purse and of the sword [Purg. 8.129]).

Guido del Duca in this way connects his friend Rinieri directly and forcibly to the discourse about heredity. Reusing the word “pregio”, he tells his friend Rinieri that his own pregio and onore, his own human worth, have not been passed on to his heirs:

Questi è Rinier; questi è ’l pregio e l’onore de la casa da Calboli, ove nullo fatto s’è reda poi del suo valore. (Purg. 14.88-90)

This is Rinieri, this is he — the glory, the honor of the house of Calboli; but no one has inherited his worth.

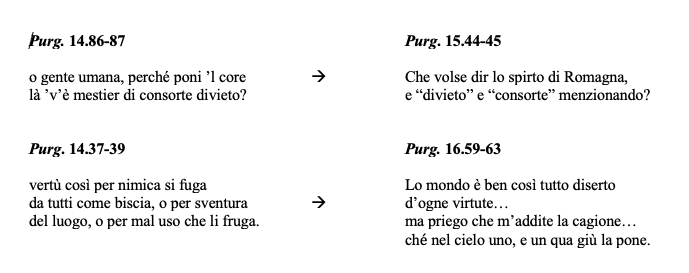

Purgatorio 14 is a canto of a certain willed opacity, whose emblem could well be Dante’s refusal to give his name in verses 20-21. Another example is the dark and obscure prophetic language used by Guido del Duca in speaking of Florence. Yet another is the opaque language used by Guido del Duca on two additional occasions, one that will be recalled in Purgatorio 15 and the other in Purgatorio 16. The opaque language of Purgatorio 14 thus textually “seeds” the next two canti, where it will bear illuminating fruit.

Dante sows discursive “seeds” in Purgatorio 14. Guido del Duca’s opaque language will bear fruit in Purgatorio 15 and 16. Purgatorio 14.86-87 will be reprised in Purgatorio 15.44-45. And Purgatorio 14.37-39 will be reprised in Purgatorio 16.59-63.

Let us begin with the passage that is reprised in Purgatorio 15:

Di mia semente cotal paglia mieto; o gente umana, perché poni ’l core là ’v’è mestier di consorte divieto? (Purg. 14.85-87)

From what I’ve sown, this is the straw I reap: o humankind, why do you set your hearts there where our sharing cannot have a part?

In these verses Guido del Duca gives a synthetic and profound definition of envy, explaining it in terms of the dialectic between self and other. Envy occurs because we desire to possess things that cannot be shared with others: things that diminish when shared, material things. This synthetic definition will lead to Virgilio’s explanation of the difference between material goods and spiritual goods in the next canto.

Guido del Duca’s synthetic definition also becomes part of the story-line of these canti of Purgatorio, for it turns out that the pilgrim did not understand them. In the next canto Dante asks Virgilio to explain what Guido del Duca’s words mean:

Che volse dir lo spirto di Romagna, e ‘divieto’ e ‘consorte’ menzionando? (Purg. 15.44-45)

What did the spirit of Romagna mean when he said, ‘Sharing cannot have a part’?

The pilgrim has certainly shown confusion to Virgilio before now, and has solicited explanations; he has also asked for his teacher’s feedback on comments that were unclear and threatening to him, like Farinata’s prophecy of his exile (Inferno 10). Here Dante-pilgrim goes so far as to cite verbatim from what was said to him by a soul, asking for a gloss of opaque and unclear words. Given that the pilgrim puts this question to his guide, and that Dante-poet thematizes the difficulty of the language in Purgatorio 14.86-87, we too will await Virgilio’s explanation.

The second instance of a structural and productive opacity in Guido del Duca’s discourse is less lexical (what do “divieto” and “consorte” mean?) and more conceptual. There is an either-or in the presentation of the vicious Arno valley: is the viciousness of the inhabitants the result of bad luck or bad habit? To pose this question, Guido del Duca describes the Arno valley as a place in which everyone flees virtue as though it were a snake, an enemy. They do this — and here is the part that will generate a need for clarification in Purgatorio 16 — either because of the “ill fortune of the place” (“sventura / del luogo”) or because of the “evil habit” (“mal uso”) that goads them:

vertù così per nimica si fuga da tutti come biscia, o per sventura del luogo, o per mal uso che li fruga... (Purg. 14.37-39)

virtue is seen as serpent, and all flee from it as if it were an enemy, either because the site is ill-starred or their evil custom goads them so...

The little subordinate either/or clause, expressed in passing in a verse and a half, poses the fundamental issue of free will. Does Dante expect us to fail to notice the subordinate clause that holds so much theological potential? Or have there been readers through the centuries in which these easily bypassed words have worked as they work on the pilgrim, who in Purgatorio 16 will express a profound need to address them?

The problem that they pose, between sventura (bad luck or bad fortune) and mal uso (bad habit), will come to a head in Purgatorio 16, where the pilgrim formulates the question that troubles him. The reply will be the Commedia‘s first great discourse on free will. The absence in Inferno of an explicit theology of free will is part of what I call Dante’s “backward pedagogy” (see “Dante, Teacher of his Reader” in Coordinated Reading).

In many ways, Purgatorio 14 continues to meditate on the binary sventura versus mal uso, without however openly addressing the theological issue here posed. Guido del Duca refers to the Arno as “la maladetta e sventurata fossa” (ill-fated and accursed ditch [Purg. 14.51]), thus reprising the word sventura from verse 38, and suggesting that the valley of the Arno is indeed a place of evil fortune. On the other hand, Purgatorio 14 ends with Virgilio’s strong denunciation of human laxness and lack of vigilance, as we defiantly take the bait offered by the devil and ignore the heavens that call out to us.

The concluding portrait of a human race focused on earthly things, those things that cause envy as Guido del Duca has explained, and thereby ignoring the celestial beauties that call out to us, definitely suggests that our mal uso is at fault. And, indeed, we know that the gate of Purgatory is dis-used because of humanity’s evil ways: “la porta / che ’l mal amor de l’anime disusa” (the gate that our evil love dishabituates us from using [Purg. 10.1-2]).

Return to top

Return to top