- a new beginning: the start of lower Hell and entry into the domain of fraud

- the eighth circle has a name: “Malebolge” (evil ditches or evil trenches)

- the eighth circle boasts a built environment — urban and architectural — as compared to the perverted natural environment of the circle of violence

- here we find devils as guardians, compared to the classically inspired and animal-based guardians of upper Hell

- Dante’s emphasis on the semiotic nature of fraud

- Dante features Italian cities in Malebolge; in this canto they are Bologna and Lucca

- political identity as linguistic identity (“sipa” as the Bolognese for “yes”) and the connection to De vulgari eloquentia

- the presence of sexualized sins and sinners

- Malebolge features sinners who are coupled: one taken from the classical world and one taken from the contemporary world

- Inferno 18 offers two sets of classical/contemporary couples

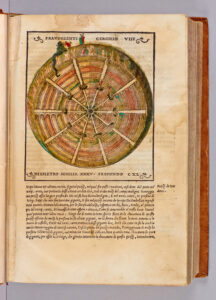

[1] Inferno 18 is the first canto devoted to the eighth circle of Hell, the circle of fraud. The enormous eighth circle, featuring souls who committed ten different varieties of fraudulent sin, extends from Inferno 18 all the way to Inferno 30. The eighth circle makes up 38% of Dante’s Hell, textually speaking. Its immensity is reflected in the number of its subdivisions: the eighth circle is subdivided into ten “evil ditches” or “evil trenches” — hence the name that Dante coins, “Malebolge”. Each trench houses a different kind of fraud.

[2] The opening verse of this canto self-consciously marks a narrative new beginning within the economy of Inferno. This — finally — is the true entrance to lower Hell:

Inferno 18 constitutes an emphatic new beginning situated at the canticle’s midpoint, at its narrative mezzo del cammin. “Luogo è in inferno detto Malebolge” (There is a place in hell called Malebolge) begins the canto, with a verse that is crisply informative, explicitly introductory, and patently devoted to differentiation: this is a new place, a new locus. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 74).

[3] The first verse of Inferno 18 — “Luogo è in inferno detto Malebolge” — is interesting on a number of counts. First, its merging of the Latinate formula “Luogo è” (“locus est”) with Dante’s plebeian neologism “Malebolge” will be mirrored in the narrative: as we shall see, Dante will deliberately couple classical figures with contemporaries throughout the eighth circle.

[4] I have discussed Dante’s ongoing cultivation of techniques of verisimilitude that do the work of staking truth claims in his possible world. An example from Inferno 5 is the casual dropping of the placename “Caina” in verse 107, used for the part of lowest Hell where Gianciotto’s soul is destined to go for killing his wife and his brother: “Caina attende chi a vita ci spense” (Caina waits for him who took our life [Inf. 5.107]). In Inferno 5.107, Dante treats his possible world as so real that the reader will know what Caina is, although the place is invented by him as part of his fictional afterlife.

[5] Similar in Inferno 18 is Dante’s deployment of the little word “detto” in verse 1: “There is a place called Malebolge” (Inf. 18.1). Dante uses the apparently innocent and mostly unnoticed past participle “detto” to subliminally convey the information that “Malebolge” exists somewhere other than in his mind. By saying that the place is “called Malebolge”, Dante seeks to give “Malebolge” currency as a word that designates a real place, suggesting that it comes frequently off the tongues of some set of humans. To say “Luogo è in inferno detto Malebolge” (There is a place in hell called Malebolge [Inf. 18.1]) is to treat Malebolge as an accepted place on a real map, a place that is “called Malebolge” by someone.

[6] I cite again from The Undivine Comedy: “the line, ‘Luogo è in inferno detto Malebolge,’ confers truth status on the locus it names by implying that it is so named by others — by whom, after all, is this place ‘called’ Malebolge?” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 75). By whom, indeed, is this place called Malebolge? Given that Dante invented the name, there can have been no one who uttered it until the existence of Inferno 18. But we never pose the question “detto da chi?” — said by whom? We do not pose it because Dante’s verisimilar art has lulled us into acceptance of his invented reality.

[7] I turn now to the question of Inferno 18’s style, and style in lower Hell more broadly. In the narrative/stylistic analysis of the canti of lower Hell in The Undivine Comedy, Chapter 4, I write as follows about the style of Malebolge and the style of Inferno 18 in particular:

From the stylistic perspective, these cantos run the gamut from the lowest of low styles to the highest of high; here too, canto 18 is paradigmatic, moving in its brief compass from vulgar black humor — “Ahi come facean lor levar le berze / a le prime percosse! già nessuno / le seconde aspettava né le terze” (Oh, how they made them lift their heels at the first blows! Truly none awaited the second or the third [37-39]) — to the solemnity with which Vergil displays Jason — “Guarda quel grande che vene” (Look at that great one who comes [83)]) — to the nastiness of the merda in which the flatterers are plunged. For Barchiesi, such transitions constitute the essence of canto 18; he suggests that the canto’s most singular aspect is its violent juxtapositioning of elevated language with realistic language, of the Latinate “Luogo è” with the plebeian neologism “Malebolge.” This insight can be extended to the cantos of Malebolge as a group, whose violent stylistic transitions provide an implicit commentary on the questions of genre and style that were opened up for the poem by the use of the term comedìa in the Geryon episode. (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 75-6)

[8] One of the key features of Dante’s Inferno, notable in Malebolge, is the extraordinary narrative and stylistic variatio that makes turning the page into a new canto a continual encounter with the new.

[9] In stylistic terms, I classify Inferno 18 as mainly a “low” style canto, whereas, for instance, the following canto belongs mainly to the “high” style. A caveat: these categories should never be taken as monolithic, since even when Dante has designated a certain section or canto as mainly belonging to a particular register or style, he nevertheless always includes some variety.

[10] Although Inferno 18 contains different stylistic registers, it is famous for the lowly merda in which the flatterers are immersed. Indeed, in later periods many authors and arbiters of style issued rebukes to Dante for the language of Inferno 18.

[11] The language and style of Inferno 18 clarify the nature and the properties of comedìa, as this text was recently named during the Geryon episode (see Inferno 16.128 and the end of the Commento on Inferno 16). We are now in a position to understand better what comedìa is: a form of writing that willingly embraces every kind of language and style, because it represents all of reality.

[12] The ongoing meditation on the nature of comedìa that runs through the post-Geryon canti includes the contrast between comedìa, which can be low as well as high, and the epics of classical antiquity, which are composed in an unremittingly high style.

[13] The contrast between the mixed vernacular style and the high style of classical epic is reflected in another narrative element that we can associate with Malebolge: the classical/contemporary couple. In this part of Hell Dante goes out of his way to couple contemporary figures with classical figures. The classical/contemporary couples of lower Hell are indexed to the poet’s ongoing meditation on comedìa and tragedìa, a meditation that is particularly strong in Malebolge.

[14] The coupling of classical with contemporary souls is spectacularly on display in Inferno 18. Two of the ten trenches of Malebolge are sandwiched into this one canto, and Inferno 18 actually boasts two sets of classical/contemporary couples, one couple in each bolgia: Venedico Caccianemico and Jason in bolgia 1, and Alessio Interminelli and Thaïs in bolgia 2.

* * *

[15] The circle of fraud consists of ten bolge, or ditches, which are packed with sinners. Eight of the ten categories of fraudulent sinners are named in the below terzina from the discussion of the structure of Hell in Inferno 11. This passage refers to hypocrites, flatterers, sorcerers, falsifiers, thieves, simonists, panders, grafters and “similar trash”, in an out of order jumble of fraudulent sinners:

ipocresia, lusinghe e chi affattura, falsità, ladroneccio e simonia, ruffian, baratti e simile lordura. (Inf. 11.58-60)

hypocrisy and flattery, sorcerers, and falsifiers, simony, and theft, and barrators and panders and like trash.

[16] Inferno 18 is unusually crowded from a taxonomic perspective, housing three groups of sinners, who are divided into two bolge. Thus, one canto contains two bolge which contain three kinds of sinners: the first bolgia contains pimps and seducers, while the second bolgia contains flatterers.

[17] The pimps and seducers of the first bolgia are housed together because they are related as sinners; both groups engaged in sexualized sin involving the traffic of women. It is evident that in such a taxonomically crowded canto, there will not be the opportunity for one sinner’s character to impose itself. Rather than character development, we note the classical/contemporary couple of the first bolgia: the pimp, Venedico, is Bolognese, while the seducer is Jason, classical hero and leader of the Argonauts.

[18] The two groups of the first bolgia circle the perimeter of the bolgia, moving in opposite directions from each other. The manner of their opposed circling is somewhat reminiscent of the method used by Dante in Inferno 7, where he previously treated a “double” sin, in that case pitting against each other the misers and the prodigals. The second bolgia contains only one group — the flatterers — who do not move at all: rather they are to different degrees immersed in shit.

[19] The pimps of bolgia 1 and the flatterers of bolgia 2 are named in the summary tercet of Inferno 11: see, in the above citation, “lusinghe” (flattery) in Inferno 11.58 and “ruffian” (pimps) in Inferno 11.60. Inferno 18 is unusual in containing two bolge in one canto, giving an impression of souls packed into Hell like commuters in a packed subway car. The crowded feel of these two bolge is enhanced by the two sets of sinners comprised in the first bolgia.

[20] An aspect of Inferno 18 that is ripe for future exploration is the gendered and sexualized discourse featured throughout the canto.

[21] The first soul with whom the pilgrim speaks does not want to be recognized, another common trait of sinners in lower Hell. But Dante persists in addressing him, asking him whether he is Venedico Caccianemico, and inquiring as to what has led him to “such pungent sauces” (“sì pungenti salse” [Inf. 18.51]). In explaining what has brought him to the bolgia of pimps and seducers, Venedico offers a synthetic account of a sordid tale. He pimped his sister, Ghisolabella (“beautiful Ghisola”), constraining her to do the will of the Marquis, who paid him for his services: “I’ fui colui che la Ghisolabella / condussi a far la voglia del marchese” (For it was I who led Ghisolabella / to do as the Marquis would have her do [Inf. 18.55-56]).

[22] A number of interesting points emerge from the pilgrim’s brief colloquy with Venedico Caccianemico. In the verses in which Venedico describes what he did to his sister, he casts both himself and the Marchese as agents — one constrained Ghisolabella and the other profited sexually — while casting the woman as the victim.

[23] The men who victimize Ghisolabella are men of power: Venedico was a powerful Bolognese Guelph, while the “Marchese” of verse 56 is Opizzo II d’Este, lord of Ferrara. Ghisolabella’s brother functions as a pimp (hence a devil will call him “ruffian” in verse 66): he sold sexual relations with his sister to Opizzo II d’Este, who purchased them. These are men for whom women are “femmine da conio”, as accurately noted by the devil who beats Venedico and sends him on his way: “Via, / ruffian! qui non son femmine da conio” (Be off, pimp, here are no women for you to sell [Inf. 18.65-6]]). Chiavacci Leonardi glosses “da conio” thus: “da moneta, cioè da prostituire per guadagno” (women for money, in other words to be prostituted for financial gain [Inferno commentary, ad locum]). The financial aspect of the transaction connects it to fraud and deceit rather than simply to violence. Financial motivations will pulse throughout Malebolge.

[24] Violence is certainly present, however. Opizzo II is among the tyrants in the circle of violence, and is named in Inferno 12:

e quell'altro ch’è biondo, è Opizzo da Esti, il qual per vero fu spento dal figliastro sù nel mondo. (Inf. 12.110-12)

that other there, the blonde one, is Obizzo of Este, he who was indeed undone, within the world above, by his fierce son.

[25] Immersed up to his brows in the river of blood in Inferno 12, Opizzo d’Este was violent toward others in both their persons and their possessions. The phrase “far la voglia del marchese” in Inferno 18.56 — to do the will of the Marquis — captures the nature of a man for whom others exist only as objects. At the same time, the few verses referring to Opizzo in Inferno 12 remind us that violence breeds violence, for Opizzo was killed by his son.

[26] We can see a vast interconnected network taking shape. The links between the souls of Dante’s afterlife have yet to be fully explored and mapped. As I wrote in “Only Historicize” (cited in Coordinated Reading): “The Commedia includes an amazing web of family — and hence political — interconnectivity spun by Dante, who so carefully chose and enmeshed the characters of his great poem” (p. 49).

[27] Venedico’s account will also include the semiotic and representational dimension that is so heightened in the post-Geryon world. Venedico refers to the “sconcia novella” (filthy tale) that circulates about him and his sister, in various permutations: “come che suoni la sconcia novella” (however they retell that filthy tale [Inf. 18.57]). He thus alludes to the oral dimension of gossip and scandal, giving his behavior a precise civic and local contour. Venedico specifically implicates his fellow Bolognesi in his sin of pimping women for financial gain, saying “E non pur io qui piango bolognese” (I’m not the only Bolognese who weeps here [Inf. 18.58]).

[28] In referring to his fellow Bolognese, Venedico characterizes them geographically and linguistically: they are those living between the rivers Savena and Reno and who say “sipa” for “sì” (verses 60-61). In characterizing the Bolognese by their use of the affirmative adverb “sipa” Dante draws on his own background as a linguist and writer on language. He first uses the affirmative adverb as a marker of political identity in his linguistic treatise De vulgari eloquentia, where he distinguishes between Italian, French, and Occitan by their modes of affirmation. Italian is the language that uses “sì” to say “yes”:

Totum vero quod in Europa restat ab istis, tertium tenuit ydioma, licet nunc tripharium videatur; nam alii oc, alii oïl, alii sì affirmando locuntur; ut puta Yspani, Franci et Latini. (De vulgari eloquentia 1.8.5)

All the rest of Europe that was not dominated by these two vernaculars was held by a third, although nowadays this itself seems to be divided in three: for some now say oc, some oïl, and some sì, when they answer in the affirmative; and these are the Hispanic, the French, and the ItaIians. (trans. Steven Botterill)

[29] In Inferno 18, Dante picks up from the De vulgari eloquentia the custom of identifying languages from their modes of saying “yes” and creates a new subset for the Italian peninsula. He adds the Bolognese “sipa” to the larger category “sì” that he used for Italian in his earlier linguistic treatise.

[30] The characterization of the Bolognese in Inferno 18 includes a reference to “il nostro avaro seno” (our avaricious hearts [Inf. 18.63]). It is worth recalling the distinction, first discussed in the Commento on Inferno 6, between the vices that trigger sin and the specific sinful actions that follow, and for which we are damned if we do not repent. We recall that avarice is one of the seven capital vices, one of the impulses that cause us to sin. In this case, avarice is the vice and the prostituting of women for money is the sin.

* * *

[31] In this canto of sexualized sin, the women whom Dante features run the gamut from passive victim to aggressor: Ghisolabella is portrayed as victim, Hypsipyle as both victim and aggressor, like Medea, while Thaïs is depicted solely as aggressor.

[32] The second group of sinners in the first bolgia is that of the seducers and features the great classical hero Jason, in his role as seducer and impregnator of Hypsipyle. Again the sexualized and gendered components of Dante’s account are noteworthy. Hypsipyle and the women of Lemnos are not simply victims, for the backstory of their murder of the men of Lemnos is acknowledged. In recounting the backstory, the language is highly gendered, pitting the “femmine” against the “maschi”: “l’ardite femmine spietate / tutti li maschi loro a morte dienno” (its women, bold and pitiless, / had given all their island males to death [Inf. 18.89-90]).

[33] But Dante subsequently, just a few verses later, depicts Hypsipyle no longer as the aggressor but as the quintessential seduced and abandoned female: “Lasciolla quivi, gravida, soletta” (And he abandoned her, alone and pregnant [Inf. 18.94]). Here the language renders Hypsipyle’s vulnerability, and the two adjectives “gravida, soletta” replace the two adjectives used for the women of Lemnos, the “ardite femmine spietate”: the “bold and pitiless” Hypsipyle is now “pregnant and all alone”.

[34] With “ornate words” — “parole ornate” that remind us of Virgilio’s “parola ornata” in Inferno 2.67 — Jason deceives Hypsipyle semiotically: “Ivi con segni e con parole ornate / Isifile ingannò” (With polished words and love signs he took in / Hypsipyle [Inf. 18.91-2]). The emphasis here is on Jason’s deception of her: “Isifile ingannò” (he deceived Hypsipyle). But Dante then repurposes the verb ingannare to make Hypsipyle the agent of deceit, reminding us that Hypsipyle, now deceived by Jason, had previously deceived the women of Lemnos, when she saved her own father from their mass murder of the island’s men: “la giovinetta / che prima avea tutte l’altre ingannate” (the girl whose own deception / had earlier deceived the other women [Inf. 18.92-3]).

[35] In the compressed compass of his Hypsipyle narrative, Dante manages to convey the way in which Hypsipyle whipsaws between being the one who harms and the one who is harmed. Deceit is a common denominator in both parts of her story.

[36] In verse 100 Dante transitions to the bolgia of flattery, where he sees “people plunged in excrement that seemed / as if it had been poured from human privies”: “gente attuffata in uno sterco / che da li uman privadi parea mosso” (Inf. 18.113-4). The inventive rhyme-words, taken from everyday life and resolutely non-literary — for instance “scuffa”/“muffa”/“zuffa” (Inf. 18.104-8) — are used to give a plebeian tone to the degraded surroundings of the final two sinners of Inferno 18.

[37] Dante sees a man whose head is so covered with shit that it is impossible to discern whether he is lay or cleric: “vidi un col capo sì di merda lordo, / che non parëa s’era laico o cherco” (I saw one with a head so smeared with shit, / one could not see if he were lay or cleric [Inf. 18.116-7]). With this aside, the poet reminds us that back in Inferno 7 he was able to recognize the clerics among the misers of the fourth circle, a group that includes cardinals and popes: “Questi fuor cherci, che non han coperchio / piloso al capo, e papi e cardinali” (These to the left — their heads bereft of hair — were clergymen, and popes and cardinals [Inf. 7.46-7]). In the fourth circle, Dante was able to discern the tonsured heads of the clerics; now such details are not visible, because of the excrement that covers them.

[38] The pilgrim forcefully names this sinner, Alessio Interminelli of Lucca (Inf. 18.122), despite the sinner’s unwillingness to be named. Both Italian sinners in this canto crave anonymity, and both have long and mellifluous names that Dante seems to delight in spreading out over the length of the verse: first “Venedico se’ tu Caccianemico” (You are Venedico Caccianmico [Inf. 18.50]), and then “e se’ Alessio Interminei da Lucca” (You are Alessio Interminelli of Lucca [Inf. 18.122]).

[39] There is a division of labor in Inferno 18 between Dante (a contemporary who identifies contemporary souls) and Virgilio (an ancient who identifies ancients) that is keyed to the contemporary/classical couplings of the souls.

[40] In bolgia one the pilgrim recognizes and names Venedico, while Virgilio points to Jason: “Quelli è Iasón” (That one is Jason [Inf. 18.86]). In bolgia two the pilgrim recognizes and names Alessio, while Virgilio points to Thaïs. This division of labor is reflected in linguistic markers as well: Venedico claims that Dante constrains him to reveal himself because he speaks with a “chiara favella” (plain speech [53]), while Virgilio notes approvingly Jason’s “parole ornate” (polished words [Inf. 18.91]). Moreover, Virgilio demonstrates open admiration for Jason, a hero, complimenting his “regal aspect”: “quanto aspetto reale ancor ritene!” (how he still keeps the image of a king! [Inf. 18.85]).

[41] The division of labor between Dante and Virgilio in Inferno 18 anticipates the pièce de résistance of classical/contemporary couples in Malebolge: Ulysses and Guido da Montefeltro. Virgilio insists that he should be the one to speak to Ulysses (Inferno 26), because he is Greek, and then instructs Dante to address Guido da Montefeltro, given that Guido is Italian (Inferno 27).

[42] The last figure in Inferno 18 is the classical Thaïs, who is a whore in Terence’s comic play Eunuchus. This is a play that Cicero cites in De Amicitia 26.98 and Cicero is most likely Dante’s source. Dante misunderstands his source and inverts the flatterer and the flattered, ascribing the wrong role to Thaïs.

[43] The erudite and Latinate context from which Thaïs derives does not preclude her being described in the sexualized terms that we have seen throughout Inferno 18. She is the “sozza e scapigliata fante / che là si graffia con l’unghie merdose” (that besmirched, bedraggled harridan / who scratches at herself with shit-filled nails [Inf. 18.130-1]). The adjective “scapigliata” in verse 130 specifies literally the courtesan’s “tousled hair”, effectively her “bedroom hair”.

[44] The adjective “scapigliata” reminds us of our long history of sexualizing female hair — and reminds us too that Dante does not sexualize hair in Inferno 5’s treatment of lust. Dante does not do what the painter Giotto does in his Last Judgment, where he hangs lustful female sinners from their long hair. But Dante does sexualize hair with respect to Thaïs in Inferno 18, and he does so again with respect to Manto in Inferno 20. For the sexualizing of hair and Dante’s avoidance of it in his treatment of lust in the Commedia, see “Dante’s Sympathy for the Other”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

[45] The vulgarity of the Dantean verse that conjures Thaïs’ past profession, “e or s’accoscia e ora è in piedi stante” (and now she crouches, now she stands upright [Inf. 18.132]), stands in fascinating contrast to the dialogue that follows between Thaïs and her lover, most likely translated from Cicero’s De Amicitia. The courtesan speaks flatteringly, with overwrought and excessive courtesy:

Taide è, la puttana che rispuose al drudo suo quando disse “Ho io grazie grandi apo te?”: “Anzi maravigliose!”. (Inf. 18.133-35)

That is Thais, the harlot who returned her lover’s question, “Are you very grateful to me?” by saying, “Yes, enormously.”

[46] For Dante, the perfumed nature of Thaïs’ brief speech act is linguistic deceit in action. The narrator makes the deceitfulness of Thaïs’ speech clear by affirming what she is, insisting on her essentialized nature as a “puttana” in verse 133: a whore, someone incapable of engaging in courteous language unless for reasons of deceit. In the essentialized language that makes Thaïs a puttana, Dante gives us his final sexualized sinner of Inferno 18.

Return to top

Return to top