Purgatorio 31, with Purgatorio 30, belongs to the microcosmic core of the canti of the Earthly Paradise, encircled by the macrocosm that treats world-historical events (see the diagram at the end of Purgatorio 28). Here Dante’s personal life and personal choices are at stake.

Purgatorio 31 continues Beatrice’s rebuke, begun in the previous canto, where she vigorously expresses her dismay that Dante, after her death, had “taken himself from me and given himself to others”: “questi si tolse a me, e diessi altrui” (Purg. 30.126).

In Purgatorio 31, she refers again to these “others”, now as “sirens” — “serene” (Purg. 31.45). She thus makes explicit the connection between the burden of her rebuke and the dream of seduction in Purgatorio 19. As Ulysses was turned from his path by the dolce serena of Dante’s dream, so was Dante himself turned from his path by various sirens whom he encounterd.

Moreover, Dante’s “error” (“errore” in verse 44) in listening to sirens was the greater because he had been given Beatrice, the most perfect of human objects of desire. He should have been able to follow her — even after her death —, thus moving always in the proper direction:

Tuttavia, perché mo vergogna porte del tuo errore, e perché altra vota, udendo le serene, sie più forte, pon giù il seme del piangere e ascolta: sì udirai come in contraria parte mover dovieti mia carne sepolta. (Purg. 31.43-48)

Nevertheless, that you may feel more shame for your mistake, and that—in time to come— hearing the Sirens, you may be more strong, have done with all the tears you sowed, and listen: so shall you hear how, unto other ends, my buried flesh should have directed you.

Similarly, Augustine writes in the Confessions that, after the death of his friend, “My soul should have been lifted up to you, Lord” (Conf. 4.7).

Who are these sirens who tempted Dante after Beatrice’s death? They are both real/historical and allegorical/symbolic.

Dante’s love poetry contains the names of many ladies other than Beatrice, including one, the donna petra (stony lady) to whom he wrote the rime petrose or stony poems (circa 1296): four canzoni that are certainly among the most charged and compellingly beautiful erotic verse ever written. The second half of the Vita Nuova hinges on the compassion shown to Dante by a beautiful lady (the donna gentile) after Beatrice’s death, and his subsequent falling in love with her. In the sonnet Parole mie, Dante writes openly of “quella donna in cui errai”: “that lady in whom I erred” (Parole mie, 3). All the ladies who caused him to err after Beatrice’s death, from the donna gentile to the donna petra, are now lumped into the accusation “diessi altrui” (Purg. 30.126): he gave himself to others.

The Convivio returns to the donna gentile episode of the Vita Nuova, more than a decade later, to claim — defensively — that the donna gentile never existed. That is, she never existed in material reality. Rather, he now claims that all along she was really Lady Philosophy. At this stage, in meeting with Beatrice at the top of Mount Purgatory, all seductions are on the table: whether they be flesh and blood or philosophical.

The theme of whether one should be constant in love or whether variability in love is to be expected is one to which Dante is deeply drawn: he begins to treat this question in his earliest poetry and returns to it throughout his life. Indeed, the defensive maneuver of the Convivio, the use of allegory to refashion the donna gentile into Lady Philosophy, is one of Dante’s responses to the charge of inconstancy — of errancy. (See the essay “Errancy”, cited in Coordinated Reading.)

This charge culminates in Beatrice’s purgatorial rebuke. She settles the matter: constancy is required, even when the beloved has died. In requiring constancy toward a dead beloved, Beatrice validates an unconventional position that Dante had adopted as early as the Vita Nuova. This edict is stated in the sonnet L’amaro lagrimar (Vita Nuova 37):

Voi non dovreste mai, se non per morte, la vostra donna, ch’è morta, obliare.

Unless you die, you should not ever be forgetful of your lady who has died.

The position adopted in L’amaro lagrimar is not a conventional position for lovers in the previous lyric tradition. It became conventional after Dante, because it was adopted by Petrarch, and from Petrarch the convention of the dead beloved entered the mainstream of the European lyric tradition. This is another of Dante’s forgotten but exploited “inventions”. (See the Commento on Purgatorio 29 for Dante’s invention of the “triumph” as a literary genre.)

In my commentary to the donna gentile sonnets of the Vita Nuova, I write about Dante’s “refusal of normative consolation”:

This refusal of normative consolation, in both its material form as the donna gentile of the Vita Nuova and in its allegorized form as Lady Philosophy in the Convivio, is the condition sine qua non of the Commedia, whose essential plot hinges on a far more radical form of self-consolation, whereby the old love is divinized. (Dante’s Lyric Poetry: Poems of Youth and of the ‘Vita Nuova’, pp. 268-69)

Normative consolation, the turning to other friends and beloveds after the loss of one’s original friend or beloved, is discussed and dismissed by Augustine in the Confessions. In the following passage Augustine considers his attempts to console himself by turning to other friends after the death of his dear friend:

To be sure, the consolation of other friends did much to restore and renew me. In their company I loved what I loved in place of you, but it was all a great fantasy, a massive lie, corrupting our minds with their itching ears by the stimulus of heretical ideas. Yet that fantasy of mine refused to die, no matter what friends of mine might perish. (Confessions 4.8 [13]); p. 155 of the Loeb edition)

As we see, here Augustine states that the consolation he found in other friends was a “great fantasy, a massive lie”. Why? Because the others, like the friend who died, are also “mutable”, meaning that they too will die:

If souls please you, let them be loved in God, because they too are mutable, and only when attached to God do they find a firm foundation. If they went anywhere else they would perish. (Confessions 4.12 [18]; pp. 161-163 of the Loeb edition)

This concept, that death should function as a prophylactic, immunizing one from further desire for other “mutable” — mortal — creatures, is the core of the Augustinian message. In the Confessions Augustine wrote of the death of a dear friend as the death that liberated him from loving other mortal creatures, because it taught him the error of loving mortal beings as though they are not mortal: “diligendo moriturum ac si non moriturum” — “loving a man that must die as though he were not to die” (Conf. 4.8 [13]; p. 154 of the Loeb edition).

Beatrice’s view of the fallacy of earthly desire recalls Augustine: “e volse i passi suoi per via non vera, / imagini di ben seguendo false, / che nulla promession rendono intera” (he turned his steps along a not true path, following false images of good that satisfy no promise in full [Purg. 30.130-32]). The false imagini di ben — false images of the good — that satisfy no promise in full are like Augustine’s “massive lie”: they are false not because they are bad, but because they are mutable, because they are mortal.

Dante’s original desire for Beatrice was not in itself wrong; indeed his desire for Beatrice led him to love “the good beyond which there is nothing to aspire”: “i mie’ disiri, / che ti menavano ad amar lo bene / di là dal qual non è a che s’aspiri” (Purg. 31.22-24). What was wrong was his failure, after her death, to resist the siren song of the new, the new objects of desire that are false if for no other reason than that they are mortal, corruptible, confined to the present and doomed to die.

In Augustinian logic, to be present — rather than eternal — is to be false: “Le presenti cose / col falso lor piacer volser miei passi” (Present things with their false pleasure turned my steps [Purg. 31.34-35]).

It is at this juncture that the Augustinian message leaves the realm of ethics for the realm of metaphysics. Or, rather, it grafts an ethical concept — falseness — onto the metaphysical idea of the present versus the eternal.

In Purgatorio 31, Beatrice continues to hammer on the theme of appropriate objects of desire: her own perfection as a mortal being was the lens that should have put everything into perspective for Dante and kept him from straying. We come back thus to the fundamental contrast between the Only Primary Good and the Host of Secondary Goods.

The core of Beatrice’s argument is that Dante had already experienced the most superior of secondary goods in her, and that therefore after her death — which is to say, after the experience of her “failure”, because of her mortality, to deliver complete fulfillment — his obligation was to learn from her death and to turn to the One Primary Good.

Beatrice’s precise language for this process is as follows. Since Dante had already witnessed in Beatrice the highest mortal beauty — the “sommo piacer” of Purgatorio 31.52 — he should not have been distracted by lesser beauty after losing her. Rather, her death should have functioned as a prophylactic against any further desiring of secondary goods:

Mai non t’appresentò natura o arte piacer, quanto le belle membra in ch’io rinchiusa fui, e che so’ ’n terra sparte; e se ’l sommo piacer sì ti fallio per la mia morte, qual cosa mortale dovea poi trarre te nel suo disio? Ben ti dovevi, per lo primo strale de le cose fallaci, levar suso di retro a me che non era più tale. Non ti dovea gravar le penne in giuso, ad aspettar più colpo, o pargoletta o altra novità con sì breve uso. (Purg. 31.49-60)

Nature or art had never showed you any beauty that matched the lovely limbs in which I was enclosed—limbs scattered now in dust; and if the highest beauty failed you through my death, what mortal thing could then induce you to desire it? For when the first arrow of things deceptive struck you, then you surely should have lifted up your wings to follow me, no longer such a thing. No green young girl or other novelty— such brief delight—should have weighed down your wings, awaiting further shafts.

The Augustinian perspective of the above passage is clear. Mortal things — the “cosa mortal” of verse 53 — fail us: they are “le cose fallaci” — the false things — of verse 56. Again, there is a strict equivalence between the adjectives “mortale” and “fallace”.

All mortal things fail us — we note the verb fallire in “sì ti fallìo” of verse 52 — and they fail us because they are mortal. They fail us because they are of “such brief use”: “si breve uso” in verse 60.

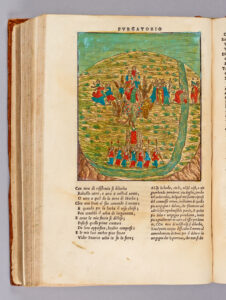

At Purgatorio 31.80, the canto shifts; everything changes. Dante sees Beatrice focused now not on him but on the griffin, the animal that is “one person in two natures”: “fera / ch’è sola una persona in due nature” (Purg. 31.80-81). With this succinct evocation of Christ’s dual nature as both man and God, the focus begins to move away from the microcosmic events of Dante’s life to the macrocosmic events of human providential history.

Return to top

Return to top