- The beginning of the voyage is interrupted, and beginning-ness is incrementalized, made life-like

- Genre: the protagonist is both a lyric/romance individual, “io sol uno” (I myself alone [3]), and an epic poet, invested in the history and culture of his people, as in the epic invocation to the Muses (verses 7–9)

- The protagonist fears that he is not qualified to undertake this journey through the afterlife, given that he is “not Aeneas, not Saint Paul” (32), and that by taking this journey he risks being a transgressor, a “Ulysses” bent on a mad and reckless voyage: “temo che la venuta non sia folle” (I fear my venture may be mad [35])

- Christian visionary phenomenology: 1) the presence of the body, “e fu sensibilmente” (with his live body [15]); 2) the raptus of Paul (see Chapter 7, The Undivine Comedy)

- Virgilio recites Beatrice’s reassuring words, thus enacting the consoling power of language and triggering the response to language: action

- The young and contemporary Florentine female is thus mediated by the venerable Roman poet, in an act of extraordinary imaginative license

- Beatrice is characterized in Inferno 2 as a speaker; this is a crucial inversion of the persona of the lyric lady, who does not speak

- Beatrice’s death and Dante’s ability to take consolation from it, conjured through precise echoes of the Vita Nuova:

- The Vita Nuova’s canzone Donna pietosa imagines Beatrice’s death in a formal structure that Dante now borrows for the narrative structure of Inferno 2

- The Vita Nuova’s canzone Li occhi dolenti stages Dante’s radical new ability to be comforted by his lady, even after her death

- Inferno 2 borrows from these Vita Nuova canzoni to develop the pre-history and the premise of the Commedia: the ability to find consolation and succor in a dead beloved

- Inferno 2 dramatizes the premise of meaningful consolation from a dead beloved with narratological flair: in a narrative flashback to a time before the action of Inferno 1

[1] As I show in Chapter 2 of The Undivine Comedy, the beginning of the Commedia is “a carefully constructed sequence of ups and downs, starts and stops; it is a beginning subject to continual new beginnings” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 28). In this way, Dante endeavors through form to create a narrative texture that imitates the path of life, in which we are always—as in the first line of Dante’s poem—in the middle. We are “nel mezzo” because time is “a kind of middle-point, uniting in itself both a beginning and an end, a beginning of future time and an end of past time” (Aristotle, Physics 8.1.251b18-26). Or, as Tolstoy writes, in the words from War and Peace that I place as epigraph at the beginning of Chapter 2 of The Undivine Comedy: “The first proceeding of the historian is to select at random a series of successive events and examine them apart from others, though there is and can be no beginning to any event, for one event flows without any break in continuity from another” (War and Peace, vol. 1, p. 975, Penguin Classics).

[2] The subversion of absolute beginning that I analyze in the “stuttering” of Inferno 1 (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 26-28) is writ large in the first six canti of Inferno, where we find what I call a “programmatic serialization of the poem’s beginning”:

The subversion of absolute beginning that we find within Inferno 1 occurs on a larger scale in the opening cantos as a group: only in canto 2 do we find the poet’s invocation to the Muses, and only in canto 3 does the pilgrim approach the gate of hell and does the actual voyage get under way. Moreover, although the first souls we see are those in hell’s vestibule, in canto 3, we do not reach the first circle, and thus the first souls of hell proper, until canto 4, and the first prolonged infernal interview does not occur until canto 5, when the pilgrim meets Francesca. This programmatic serialization of the poem’s beginning, whereby a new beginning is accorded to each of these early cantos, is most dramatically evidenced by canto 2, which effectively succeeds in postponing, and at least temporarily derailing, the beginning provided by the end of canto 1. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 28)

[3] Inferno 2 is an important moment in the poet’s programmatic serialization of his beginning, for Dante carefully undoes the beginning of the voyage that he had apparently set into motion at the end of Inferno 1. Inferno 1 ends with the pilgrim’s embrace of Virgilio as his leader and guide, and with the beginning of their journey together. In the last verse of Inferno 1, the journey begins: “Allor si mosse, e io li tenni dietro” (Then he moved on, and I behind him followed [Inf. 1.136]). And yet, the beginning instantiated at the end of Inferno 1 will be delayed, and Inferno 2 will also end with verses that signal the beginning of the journey: “Così li dissi; e poi che mosso fue, / intrai per lo cammino alto e silvestro” (These were my words to him; when he advanced / I entered on the steep and savage path [Inf. 2.141–42]).

[4] Why does Dante use canto 2 to postpone the journey that seems to begin at the end of canto 1? Canto 2 is a space of non-action that creates the possibility of action: the journey is delayed while its ideological premises are discussed. At the end of canto 2, when the journey begins again, the protagonist has been effectively issued a passport that licenses him to do the non-permissible without suffering negative consequences.

[5] By the end of Inferno 2, we know that Dante-protagonist will not be a Ulysses. He has been granted a way forward, graced to undertake a journey that is permitted only to those who are chosen, not to those who adventure on their own.

[6] In narrative terms, canto 2 is devoted to retarding the journey’s beginning, allowing for a narrative space in which these issues can be explicitly brought forward, discussed, and “resolved”, at least to the degree necessary to allow the journey to begin. It turns out that Dante-protagonist, the individual and singular historical being, the “io sol uno” (I myself alone) of Inferno 2.3, who was born in Florence in 1265, has to deal with the psychological fall-out of being chosen for such a remarkable undertaking.

[7] Moreover, this psychological fallout includes the issue of how the chosen wayfarer is viewed by others, with the result that the Commedia includes a hefty component of managing how the pilgrim is perceived. This “management” takes the form of a Ulyssean rhetoric and thematic that runs through the Commedia and that will receive ample treatment in this reading of the Inferno.

[8] Inferno 2 begins by situating the traveler and his fear in the growing dusk of the departing day, as he prepares himself for the battle that awaits him. Following the epic invocation to the Muses of verses 7–9 (another marker of incipience), Dante announces to Virgilio that he is afraid. He does not believe he is qualified to undertake such a spectacular mission. The pilgrim’s apprehension is carefully articulated through two examples of men who, in contrast to himself, he believes were indeed qualified for such remarkable undertakings. These men were chosen, elected by God: one was “ne l’empireo ciel per padre eletto” (chosen as father in the empyrean heaven [Inf. 2.21]), the other was the “Vas d’elezïone” (the Chosen Vessel [Inf. 2.28]). Dante’s fears rotate around these words, “eletto” and “elezïone”: in contrast to Aeneas and Paul, who elected Dante for such an undertaking—such an “impresa” (41)?

[9] The answer takes a while to unfold, most of the canto in fact, since Dante recounts it in a narratologically complex way: as a flashback to a time before Inferno 1 that involves characters not yet introduced. While the modality of presentation is complex, the content of the answer is ultimately quite straightforward. Virgilio explains that Dante was chosen for this undertaking, and that he, Virgilio, was chosen to come to the aid of the chosen one, the eletto. Virgilio speaks for much of Inferno 2, repeating what was said to him by Beatrice, here introduced to the dramatis personae of the Commedia. Virgilio recounts how Beatrice sought him out and motivated him to provide assistance to Dante.

[10] Moreover, the source of the assistance is in highest heaven, having its origin in the Virgin Mary herself. Mary is not named; she is the “noble lady in heaven who feels compassion”: “Donna è gentil nel ciel che si compiange” (Inf. 2.94). The account given by Virgilio, who had it from Beatrice, is as follows: the Virgin transmitted her concern for Dante to “Lucia” (97), here named for the first time. Saint Lucy then moved from her seat in heaven to go to the place where Beatrice was sitting next to “antica Rachele” (venerable Rachel [102]). Lucia asked Beatrice why she has not “helped him who loved you so / that—for your sake—he left the vulgar crowd”: “Beatrice, loda di Dio vera, / ché non soccorri quei che t’amò tanto, / ch’uscì per te de la volgare schiera?” (Inf. 2.104–05).

[11] Beatrice is here presented to readers of the Commedia for the first time. She is named two times in Inferno 2 (these are the only occasions in which Beatrice’s name appears in Inferno; elsewhere in the first cantica she is referred to by periphrasis). The first time she names herself in the magnificent self-introduction that magnifies her power to do and to accomplish: “I’ son Beatrice che ti faccio andare” (I am Beatrice who make you go [Inf. 2.70]). Her second naming occurs in the direct address uttered by Lucia and cited above, which states Beatrice’s ontological essence as “true praise of God”, a phrase to which we will return, and which then encapsulates her prior salvific mission with respect to Dante: she is the one for whom he left the vulgar crowd. This statement alludes to a history that will lead the interested reader to Dante’s lyric poetry and to his first book, the Vita Nuova. Because of the dense past that is evoked, and the forceful language that is used, Beatrice’s character is palpable, albeit presented only in flashback and at two removes from the original speaker.

[12] In this way, Dante learns that there are “three blessed ladies who care for him in the court of heaven”—“tre donne benedette / curan di te ne la corte del cielo” (Inf. 2.124–25)—and that they have chosen Virgilio to come to his immediate assistance in the dark wood. He is indeed eletto, like Aeneas and like Saint Paul.

[13] We go back now to the pilgrim’s initial statement of fear and concern and his self-comparison to two chosen ones, one classical and the other biblical.

[14] The first chosen one is Aeneas (the “father of Sylvius” in verse 13), who was able to go to Hades while still in the body: “corruttibile ancora, ad immortale / secolo andò, e fu sensibilmente” (he went to the immortal realm while still corruptible, and with his live body [Inf. 2.14–15]). The voyage of Aeneas to the underworld, as described in Book 6 of the Aeneid, is fully comprehensible, says the pilgrim, given that he was chosen in heaven as the founder of Rome and its empire, the future seat of the papacy (verses 19–27).

[15] The pilgrim continues: St. Paul too (“the chosen vessel” of verse 28) undertook an analogous journey. Dante is referring here to Paul’s statement in 2 Corinthians 12:2 that he was “caught up to the third heaven”: “raptum eiusmodi usque ad tertium caelum”. This passage stresses the unknowable status of the body: “sive in corpore nescio sive extra corpus nescio Deus scit” (whether in the body I do not know, or out of the body I do not know, God knows). Saint Paul’s journey to the third heaven was the consummate example of visionary raptus, discussed and debated by theologians for centuries.

[16] While the invocation of Saint Paul as the prototype of one who expderienced raptus is canonical, Dante is highly atypical in linking Saint Paul’s biblical raptus to Aeneas’s classical journey. This linkage is another example of Dante’s commitment to a hybrid textuality. He is committed to the contamination of biblical with classical. Moreover, the language used in Inferno 2 for Aeneas’s descent to Hades, the emphasis on his going in his body (“e fu sensibilmente”), further connects the classical pagan example to Christian visionary phenomenology. This is a tradition, as we see in 2 Corinthians 12:2 cited above, which stresses the paradoxical and inexplicable presence of the body. In this passage Dante has introduced language and references that allude to the mystical journey accomplished in the flesh.

[17] These allusions work retroactively to characterize the “sonno” of Inferno 1.11 as belonging to a special class of sleep: it is the mystical and waking sleep of the visionary, one who experiences his vision in embodied form. As per 2 Corinthians 12, where Saint Paul’s raptus immediately raises the question of the status of the body (“sive in corpore nescio sive extra corpus nescio Deus scit”), we find in Inferno 1 not only the first reference to visionary sleep, the “sonno” of verse 11, but also the first reference to the pilgrim’s “corpo”: “Poi ch’èi posato un poco il corpo lasso” (I let my tired body rest awhile [Inf. 1.28]).

[18] Within the primary vision that encompasses the whole Commedia there are opportunities for secondary faints, sleeps, and even secondary visions. For instance, the ecstatic visions of the terrace of wrath in purgatory are secondary visions, in that they are visions that occur within the overall vision that is the Commedia. Similarly, there is sleep that occurs within the overall visionary sonno: for instance, the pilgrim falls at the end of Inferno 3, “like a man whom sleep has seized”: “caddi come l’uom cui sonno piglia” (Inf. 3.136). He awakens from this secondary sonno at the beginning of Inferno 4, when a thunderbolt blasts him awake: “Ruppemi l’alto sonno ne la testa / un greve truono, sì ch’io mi riscossi / come persona ch’è per forza desta” (The heavy sleep within my head was smashed / by an enormous thunderclap, so that / I started up as one whom force awakens [Inf. 4.1–3]).

[19] As his most potent emblem of the visionary phenomenon of “waking sleep”, Dante offers the old man who figures the Apocalypse in the procession of the earthly paradise: “un vecchio solo . . . dormendo, con la faccia arguta” (a lone old man, his features keen, advanced, as if in sleep [Purg. 29.143–44]). This is John, the author of the Apocalypse (it is important to bear in mind that in Dante’s day the author of the Gospel of John and the author of the Apocalypse were held to be the same John). Saint John is in a visionary trance: “asleep”, yet keenly sighted.

[20] In this commentary, these issues, which can be classified as “visionary” and pertain to St. Paul’s raptus and to the sonno of the Commedia, will be discussed as they arise. St. John as author of the Apocalpyse, for instance, will first be discussed in the Commento on Inferno 19. For the reader who wants to consider these issues holistically, they are treated synchronically and contextualized in Chapter 7 of The Undivine Comedy. (See also my commentary to Dante’s early lyric poems for the pre-Commedia history of these themes in Dante’s work: Dante’s Lyric Poetry: Poems of Youth and of the Vita Nuova, cited in Coordinated Reading. For instance, I analyze the presence of mystical themes in the youthful sonnet Ciò che m’incontra ne la mente more.

[21] In Inferno 2, Dante weaves together the figures of Aeneas and St. Paul, the two great precursors — one classical and one biblical. As we have seen, each was chosen for good reasons to undertake his journey to the afterlife. Together, these great figures are what the pilgrim fears that he is not:

Ma io perché venirvi? o chi ’l concede? Io non Enea, io non Paulo sono: me degno a ciò né io né altri ’l crede. (Inf. 2.31-33)

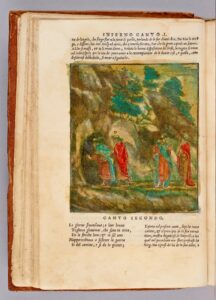

But why should I go there? Who sanctions it? For I am not Aeneas, am not Paul; nor I nor others think myself so worthy.

[22] The statement “Io non Enea, io non Paulo sono” functions, at this moment, as a statement of what the pilgrim fears he is not. But the line works ultimately as the poet’s declaration of the genealogy to which he belongs. In effect, he is saying that he is a modern version of Aeneas, and that he is a modern version of St. Paul.

[23] Virgilio then reassures the pilgrim, which he does by explaining how it is that he was sent to Dante’s assistance: as we have discussed, he was called to Dante’s aid by Beatrice, who from heaven witnessed Dante’s peril and wants to save him. She left her seat in heaven and went to Virgilio in Limbo, summoning him to be Dante’s guide. Virgilio, as we have learned, reassures Dante with words, indeed by repeating the very words that had previously been exchanged between himself and Beatrice. It is thus no exaggeration to say that words and their effects are key protagonists of Inferno 2.

[24] In this way, as a narrative flashback, Dante-poet introduces a crucial pre-history to the events of Inferno 1. The journey of Beatrice to Limbo to solicit Virgilio is an event that precedes and crucially conditions the events of Inferno 1. If we were diagramming the events of the Commedia, we would now add a new event to the timeline, namely Beatrice’s descent to hell to find Virgilio, and we would situate it prior to the events that are narrated in Inferno 1.

[25] To aid readers in visualizing my narratological analysis, I offer a timeline that illustrates the relationship between the events narrated by Virgilio in Inferno 2, events that are placed under the rubric “pre-history”, and the events that constitute the recorded “history” of the Commedia: its diegesis, its narrative. I have deliberately been sparing in choosing plot elements for inclusion on the timeline, reducing them to the most essential. The vertical dotted line separates the pre-history from the history:

TIMELINE

[26] The exercise of diagramming the Commedia’s diegesis is an effective prophylactic against suspension of disbelief. To be clear, suspension of disbelief is unavoidable, and it is indeed even pleasureable, for it is the great gift of art: it is the essential mechanism that allows the reader to exist in possible worlds different from her own, it is what allows us to be “entertained”, in the etymological sense of “held”. But, as critical readers, it is also essential to be able to suspend suspension of disbelief, if we are properly to analyze a work of art and its effects upon its audience. In other words, suspension of the suspension of disbelief is essential critical work, if we are to understand how Dante’s great poem is constructed and how it does its work.

[27] Let us take note, too, of the way that the possible world of the Inferno unfolds and accretes—or, better, of the tiny markers that Dante designs into his possible world and that he carefully unfolds as part of the process of its incremental becoming. Beatrice had to go to Limbo to speak to Virgilio, and Virgilio in Inferno 2 describes his dwelling-place in Limbo among “color che son sospesi” (those souls who are suspended [Inf. 2.52]). By characterizing the souls of Limbo with the trope of suspension, the character Virgilio anticipates the narrator’s identical description in Inferno 4: “però che gente di molto valore / conobbi che ’n quel limbo eran sospesi” (for I had seen some estimable men / among the souls suspended in that limbo” [Inf. 4.44–45]). By having his character Virgilio in this way anticipate the narrator, Dante-poet builds the verisimilitude of his possible world. The accretion of thousands of these microtropes of verisimilitude, some of which are analyzed in The Undivine Comedy, make it difficult, if not impossible, for the reader to resist the tug of the narrative’s claims to tell truth.

[28] As we have seen, in Inferno 2 Dante-poet makes Virgilio the narrator of the crucial pre-history that sets the diegesis of the Commedia in motion: Beatrice leaves heaven to go to Virgilio in Limbo, and Virgilio leaves Limbo to go to Dante in the dark wood, as the pilgrim strives to climb the mountain but is pushed back by the she-wolf. Virgilio’s account dramatizes the dynamic between sentiment on the one hand, and action on the other. This is a dynamic that will be captured by Beatrice’s beautiful words (related by Virgilio to Dante) distilling the sentiment as her love—“amor”— and the action as her speech: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (love moved me, and makes me speak [Inf. 2.72]).

[29] Beatrice’s words recounted by Virgilio echo the words used by the narrator to describe creation in Inferno 1. Love first enters the Commedia in Inferno 1’s evocation of the moment of Creation, which occurred when divine love first moved the stars in the sky: “quando l’amor divino / mosse di prima quelle cose belle” (when divine love first moved those things of beauty [Inf. 1.39-40]). Love in Inferno 2 again governs a verb of motion, in Beatrice’s great verse: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (Love moved me, that Love which makes me speak [Inf. 2.72]).

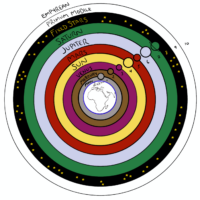

[30] The motion of the universe as the expression of God’s love for creation in Inferno 1 becomes the motion of Beatrice as the expression of her personal love for Dante in Inferno 2. In the macrocosm, divine love moved the stars at the dawn of time in Inferno 1: “l’amor divino / mosse di prima quelle cose belle” (Inf. 1.39-40). So, in the microcosm, love moved Beatrice to come to Dante’s aid, through speech: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (Inf. 2.72).

[31] Also noteworthy here is the crucial shift that Dante-poet engineers with respect to Beatrice, whom he now makes a speaker. In the courtly and stilnovist lyric, the lady does not speak. Beatrice, who began her life in Dante’s oeuvre as a silent lyric lady, now enters the Commedia characterized as a speaker, one who engages in “parlare”: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (72). Beatrice is characterized throughout Inferno 2 as a speaker, in a crucial inversion of the persona of the silent lyric lady. This inversion is all the more interesting because this canto introduces the modalities of the lyric into the Commedia and sutures Dante to his past as a lyric love poet and as writer of the Vita Nuova. By making Beatrice a speaker, Dante signals that in the Beatrice of the Commedia he is forging a new kind of female persona, an amalgam of the lyric lady with other more loquacious female literary figures, like Lady Philosophy in Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. And, while in Inferno 2 Beatrice’s speech is mediated through Virgilio, later in the Commedia her status as independent and authoritative Beatrix loquax will be fully instantiated.

[32] I first coined “Beatrix loquax”, “loquacious Beatrice”, in The Undivine Comedy (303, note 36). I developed the theme of Dante’s talkative beloved in “Notes toward a Gendered History of Italian Literature, with a Discussion of Dante’s Beatrix Loquax”, where I discuss the many sources that feed into Dante’s construction of the figure of Beatrice in the Commedia, such as Boethius’s Lady Philosophy, and also the disruptive significance of her speech:

He ruptures the connection of the Commedia’s Beatrice to her lyric past by having this Beatrice use her angelica voce — by having her speak. Because we are in hell, and Beatrice does not enter hell, her speech is reported by Vergil, but it is her speech nonetheless; it is reported verbatim and it takes up most of the canto. The fact that she speaks is central, just as central as the impulse that moves her to speak: she is moved by love, and the same force that moves her to leave heaven on Dante’s behalf also causes her to speak. The famous verse in which Beatrice states the cause of her motion and her purpose makes it equally clear that her purpose is intimately bound up with her speech: ‘‘amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare’’ (love moved me, which makes me speak) (Inf. 2.72). In this declaration that love moved her and makes her speak, Dante both conjures Beatrice’s past and scripts for her a radically new future. This future, which will unfold in the Commedia, is contained in the verb parlare, a verb betokening an activity utterly alien from the agenda of the lyric lady. (“Notes toward a Gendered History of Italian Literature, with a Discussion of Dante’s Beatrix Loquax”, in Dante and the Origins of Italian Literary Culture, p. 371)

[33] Whereas in Inferno 1 Dante combines biblical and classical echoes to create a uniquely hybrid “middling” textuality, in Inferno 2 Dante creates another form of rhetorical mixing. Now Dante mixes the vernacular and lyrical features of the courtly poetry he wrote as a young man (the dolce stil novo or “sweet new style”) with the theological underpinnings of his otherworld.

[34] By the same token, he mixes Virgilio, a historically existent “real person” who lived in classical Rome, with Beatrice, a completely different kind of historically existent real person. A contemporary of Dante’s, Beatrice is asymmetric to Virgilio: youthful, female, contemporary and Christian, as compared to old, male, classical and pagan. A Florentine woman whom he knew in his youth, Beatrice announces herself by name to the Roman poet, confident that he will know who she is:

I’ son Beatrice che ti faccio andare; vegno del loco ove tornar disio; amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare. (Inf. 2.70-72)

For I am Beatrice who send you on; I come from where I most long to return; Love prompted me, that Love which makes me speak.

[35] One of the tricky aspects of Inferno 2 is keeping track of who is speaking, given the embedding of the direct discourse of Beatrice and Lucia within the account narrated by Virgilio to Dante. We must remember that we do not “meet” Beatrice in this canto, nor do we “hear” her speak, since she is not present at the time of the conversation between Dante and his guide, which is what is actually related in Inferno 2. Rather, we hear her words, quoted by Virgilio in direct discourse: we hear the Florentine lady as she is mediated by the Roman sage.

[36] We have in this scene a signature testament to the fearless nature of Dante’s imaginative faculties. As the highest form of consolation, he conjures the words spoken by the young Florentine female intercessor, words that are repeated to him by none other than the most venerable of Roman poets. The power of words to move (the Christian preacher orates “in order to move” his audience — “ut moveat” — notes Augustine in De Doctrina Christiana Book 4, chapter 12) is dramatized in the events of Inferno 2: one heavenly lady (the Virgin Mary) spoke to another (Lucia) who spoke to Beatrice, and Beatrice then left heaven to speak to Virgilio. Love, which is motion, causes more motion: more love. And love uses language to cause motion. The ability of language to move and to persuade is at the heart of the poet’s quest in the Commedia, and he dramatizes the power of language in Inferno 2.

[37] In the tercet that precedes Beatrice’s self-presentation cited above (“I’ son Beatrice che ti faccio andare”), she speaks of needing Virgilio to employ his beautiful language to aid Dante so that she “may be consoled”:

Or movi, e con la tua parola ornata e con ciò c’ha mestieri al suo campare l’aiuta, sì ch’i’ ne sia consolata. (Inf. 2.67-69)

Go now; with your persuasive word, with all that is required to see that he escapes, bring help to him, that I may be consoled.

[38] Consolation, and the power of language to console, is a theme with a long past in Dante’s oeuvre. Beatrice is the source of Dante’s consolation from the time of Dante’s Vita Nuova and before. Written in the aftermath of Beatrice’s death, circa 1292-1293, the Vita Nuova is the work in which Dante theologizes Beatrice and his love for her.

[39] Given this autobiographical pre-history, it is all the more fascinating to see Beatrice enter the Commedia asking a third party (Virgilio) to supply for her that consolatio that in the past was her unique gift to Dante. By appropriating and transferring the word “consolata” to herself in Inferno 2, Beatrice gestures toward, and recreates in nuce, the entire early history between herself and Dante. This is a lyric account, expressed first in lyric poems and not set out in narrative form until the Vita Nuova, the text that situates those early poems in a prose frame-story, thus converting their lyricism into history.

[40] That history may be distilled into these distinct steps, each marked in the prose of the Vita Nuova and expressed in lyric poems:

[41] 1. Beatrice is a source of beatitudine: of happiness, of fulfillment, of consolation. Dante learns that Love “has placed all my beatitude in that which cannot fail me”: “ha posto tutta la mia beatitudine in quello che non mi puote venire meno” (VN 18.4). Something that cannot fail him is something that cannot be taken away, therefore something that he gives, rather than something that he seeks. The result is the realization that happiness lies in the act of praising her, “in those words that praise my lady”: “in quelle parole che lodano la donna mia” (VN 18.6–7). Thus is born the poetry of praise: “lo stilo de la sua loda” (the style of her praise [VN 26.4]), as exemplified by the sonnet Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare. The praise-style of the Vita Nuova is reprised in Inferno 2. But in Inferno 2 Beatrice is more than the object of praise. She is now praise incarnate, defined as “loda di Dio vera”: “true praise of God” (Inf. 2.103). Her being is true praise of the divine; her existence testifies to God’s greatness. She praises the transcendent ontologically, merely by existing.

[42] 2. Beatrice dies. Her death is imagined in Donna pietosa, the canzone of visionary prefigurations and consolatory female speech, placed in Vita Nuova 23. I cite from my commentary on Donna pietosa, in Dante’s Lyric Poetry:

The construction of Donna pietosa anticipates that of the second canto of Inferno, also made up of embedded speeches. Just as in Inferno 2, where there is a relay of female compassion that motivates the ladies of the court of heaven to succor the lost pilgrim, so Donna pietosa opens with the pity of one lady that elicits the compassion of others: “E altre donne, che si fuoro accorte / di me per quella che meco piangia, / fecer lei partir via, / e appressarsi per farmi sentire” (And other ladies, learning of my plight / because of her who wept there by my side, / sent her away / and came to aid in my recovery [7–10]). (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, 213)

[43] 3. While the ladies of Donna pietosa wish to console Dante — “‘Deh, consoliam costui’ / pregava l’una l’altra umilemente” (‘Let’s console him,’ / each one of them implored kindheartedly [23–24]) — after the death of Beatrice, Dante remains “disconsolate”, like the canzone on her death, Li occhi dolenti (Vita Nuova 31). I cite from my commentary on Li occhi dolenti:

In the last line the poet assigns to his canzone the label “disconsolata”, making it the emblem and spokesperson for the state of being inconsolable: “e tu, che se’ figliuola di tristizia, / vatten disconsolata a star con elle” (and you, the daughter of despondency, / go off in misery to stay with them [75-6]). (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 251)

[44] 4. The great importance of the canzone Li occhi dolenti actually lies in the consolatio that, despite everything, it manages to find. Beginning in Li occhi dolenti, Dante, who in Donna pietosa was consoled by living ladies, learns to take consolation and comfort from his dead lady. This process is explained in my commentary on Li occhi dolenti:

In Li occhi dolenti we see consolatio come to the fore in a new way: it is connected for the first time to the imaginative processes of the lover and to what he can do to obtain consolation for himself. Consolatio is now tied to the act of imagining his lady alive. We find in Li occhi dolenti not only the despondency aroused by the death of madonna but Dante’s response: his move towards a poetics that brings the dead to life. While the death of Beatrice leaves the soul despondent, in a condition of fundamental deprivation, stripped of all consolation, “d’onne consolar … spoglia” (Li occhi dolenti, 40), the ability to imagine her alive to the point of talking to her opens the door to the possibilities of consolatio. And not to the consolatio provided by books or by abstractions like Lady Philosophy, but to the consolatio provided by Beatrice herself, as emphasized by the timely repetition of her name: “chiamo Beatrice, e dico: ‘Or se’ tu morta?’; / e mentre ch’io la chiamo, me conforta” [I call to Beatrice: ‘Are you now dead?’ / And while I call on her she comforts me] (Li occhi dolenti, 55–6). (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 249)

[45] 5. Dante refuses normative consolation, in both its material form as the donna gentile of the Vita Nuova and in its allegorized form as Lady Philosophy in the Convivio. This refusal is the crucial for the Commedia:

This refusal of normative consolation, in both its material form as the donna gentile of the Vita Nuova and in its allegorized form as Lady Philosophy in the Convivio, is the condition sine qua non of the Commedia, whose essential plot hinges on a far more radical form of self-consolation, whereby the old love is divinized. (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 269)

[46] In sum, the premise to Inferno 2, the premise to the “plot” of the Commedia, is Dante’s refusal of normative consolation. He refuses both new living loves (the donna gentile of the Vita Nuova) and new allegorized loves (Lady Philosophy in the Convivio). He has to devise a method to find consolation where he had found it previously, in Beatrice. He brings her to life through the power of his mind. Already in the youthful canzone Li occhi dolenti Dante is able to speak to dead Beatrice in direct discourse and to solicit her comfort: “chiamo Beatrice, e dico: «Or se’ tu morta?»; / e mentre ch’io la chiamo, me conforta” [I call to Beatrice: ‘Are you now dead?’ / And while I call on her she comforts me] (Li occhi dolenti, 55–6).

[47] What Dante accomplishes in this passage of Li occhi dolenti is truly remarkable:

I have frequently noted the importance for Dante of direct discourse, which he uses to cross the boundaries between the imagined and the real, and in this case literally between life and death. The poet speaks directly, in the climactic expression of his suffering, to his lady, asking her, as if she were alive, “Are you now dead?”: “Or se’ tu morta?” (55). The conceptual paradox of this question is genial. Its form – not only direct discourse but the fact of its being a question, a locution that requires an interlocutor, as well as the literal and temporal meaning of the pleonastic particle “or” (“now”) – battles and almost overwhelms its substance: it is not possible for Beatrice to be dead, if one can talk to her! The poet’s question “makes her alive,” in what we might call an “optical illusion” created by words. And yet what it is that he asks her is if she is dead. (Dante’s Lyric Poetry, p. 248)

[48] In Li occhi dolenti we see how one who had been accustomed to find consolation in living Beatrice learns to find consolation in dead Beatrice.

[49] Inferno 2 thus communicates the crucial autobiographical pre-history of the Commedia: the story of how Dante learned to find consolatio in dead Beatrice. At the same time that Inferno 2 communicates the protagonist’s “true” pre-history, the canto also enacts a pre-history in its fiction, by telling of a meeting in Limbo between Beatrice and Virgilio that precedes the account of Inferno 1. Here Dante shows us one of his signature moves as a poet, which is to do what he is describing, to show rather than tell. The very idea of pre-history is neatly captured, and is in effect dramatized, by the fact that Inferno 2 recounts the pre-history of Inferno 1.

[50] In canto 2 Virgilio explains to Dante that his voyage through the three realms of the afterlife is willed by God: he is not undertaking a sacrilegious journey of hubris and transgression, but rather a journey that is fully sanctioned and licensed by divine providence. Dante-protagonist fears that his enterprise may be “folle” — “temo che la venuta non sia folle” (Inf. 2.35) — using a Ulyssean adjective whose resonance will be unpacked as the poem progresses. Dante-poet scripts both the fear and the reassurance, both raising and defusing the specter of hubris. By invoking the possibility of hubris, he is communicating that he is not self-authorized, that he is not a willful and reckless adventurer like Ulysses. His journey is fully authorized by divine authority.

[51] The author of the Commedia lets us know, by staging his fear and Beatrice’s succor — her consolation as expressed in her action and in her language — that he received license for his voyage, that the Supreme Authority granted him the way forward. He also lets us know that he has a heroic concept of language and its power to move us. And he has a heroic concept of the imagination, which can conjure a dead beloved and bring her to life.

[52] After the pilgrim has been reassured that he is not embarked on a wild venture, after he has been told by Virgilio who heard it from Beatrice that his voyage is willed by a higher power, the journey can finally begin.

Return to top

Return to top