In the previous canto we saw that the encounter between Sordello and Virgilio — their embrace based on nothing more than a shared love of a common patria — was interrupted by the poet’s need to fulminate at the various powers that are ruining Italy. At the beginning of Purgatorio 7 the story-line (the diegesis) resumes, picking up exactly where it left off in Purgatorio 6.

Since Virgilio and Sordello had not yet introduced themselves to each other when the digression of Purgatorio 6 ruptured the narrative, Purgatorio 7 begins with these introductions, the “accoglienze oneste e liete” that “furo iterate tre e quattro volte” (glad and gracious welcomings . . . repeated three and four times [Purg. 7.1-2]). Boccaccio loved these verses enough to insert them verbatim into the story of madonna Beritola, to mark the moment after she is reunited with the son whom she had lost decades previously (Dec. 2.6.69). Dante, less melodramatic (when we factor out the afterworld setting), is describing the meeting of minds of two men who have just become friends and embraced on the basis of their shared citizenship of Mantova. Sordello and Virgilio never met in the flesh, but as Sordello will explain upon learning of Virgilio’s identity, he adores Virgilio for being who he is: the greatest of Latin poets.

The expression of Virgilio’s identity — “Io son Virgilio; e per null’ altro rio / lo ciel perdei che per non aver fé” (I am Virgil, and I am deprived of Heaven / for no fault other than my lack of faith [Purg. 7.7-8]) — and the subsequent expression of Sordello’s adoration comprise the beginning of Purgatorio 7. This passage offers an important installment in the ongoing Virgilio-narrative. We note that Virgilio states his name (“Io son Virgilio”), and then immediately follows not with the information that he wrote the Aeneid (as he told the pilgrim in Inferno 1) but with information that is perhaps in his mind tailored to meeting a soul in Purgatory: “e per null’ altro rio / lo ciel perdei che per non aver fé” (I am deprived of Heaven / for no fault other than my lack of faith [Purg. 7.7-8])

Here Virgilio tells Sordello that he did not actively sin, and that he “lost Heaven” only because of his lack of Christian faith. Virgilio is making the same claim that he made in Inferno 4, when he told the pilgrim that the souls of Limbo did not sin, and that they are in Limbo only because they lack baptism: “ch’ei non peccaro; e s’elli hanno mercedi, / non basta, perché non ebber battesmo” (they did not sin; and yet, though they have merits, / that’s not enough, because they lacked baptism [Inf. 4.34-35]).

We can follow this thread in (at least) two directions. One regards our ability to evaluate Virgilio’s claim. Since Inferno 4, we have received much new information that has changed our perspective. Most recently, we met Cato of Utica on the shores of Purgatory (in Purgatorio 1), a pagan who is both saved and also guardian of Purgatory. Now that we know that pagans can be saved, we can no longer simply take at face value that Virgilio is damned only because he was not baptized.

The other thread is the one that Dante-poet will exploit immediately. It is this: Sordello does not care a whit about Virgilio’s status in the Christian afterworld. All that Sordello cares about in this moment is that before him stands the greatest of Latin poets, the “glory of the Latins”, the poet who was able to reveal in his poetry the power of “our language”. By “la lingua nostra” (our language [Purg. 7.17]), Sordello means the common language that binds Virgilio’s Latin and Sordello’s Occitan. He feels himself to belong to the same linguistic and poetic tradition that Virgilio inaugurated.

Sordello’s tribute also has important implications for Dante’s linguistic theory as expressed in De Vulgari Eloquentia and for his sense of political unity forged on a common linguistic base:

«O gloria di Latin», disse, «per cui mostrò ciò che potea la lingua nostra, o pregio etterno del loco ond’io fui...» (Purg. 7.16-18)

He said: “O glory of the Latins, you through whom our tongue revealed its power, you, eternal honor of my native city . . . ”

In his linguistic treatise De Vulgari Eloquentia, Dante had referred to Sordello as a “man of unusual eloquence, who abandoned the vernacular of his home town not only when writing poetry but on every other occasion”: “[Sordellus de Mantua] qui, tantus eloquentie vir existens, non solum in poetando, sed quomodocunque loquendo patrium vulgare deseruit” (DVE 1.15.2; trans. Steven Botterill, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Cambridge U. Press, 1996). Dante, in other words, sees in Sordello an embodiment of a kind of linguistic de-provincialism. As I write in Dante’s Poets:

No one has a better right than Sordello to speak of “Latins” or of “our” tongue; in his crossing of linguistic boundaries he showed himself to be a true cosmopolitan, or “Latin,” aware of the common heritage that underlies all the languages of

Romania and makes them interchangeable, “ours” as it were. It is not because he is as great a poet as Vergil that Sordello is chosen to eulogize him but because he demonstrates in his own person the unity of a linguistic tradition that is rooted in Latin language and literature and that cannot be divorced from a political tradition rooted in the Roman Empire. (Dante’s Poets, p. 163)

Virgilio melts at Sordello’s genuine adoration. He now adds to our store of information about Limbo, following up on his discourse in Purgatorio 3.37-45, and recalibrating the balance between virtuous pagans and unbaptized children with respect to Inferno 4:

Non per far, ma per non fare ho perduto a veder l’alto Sol che tu disiri e che fu tardi per me conosciuto. Luogo è là giù non tristo di martìri, ma di tenebre solo, ove i lamenti non suonan come guai, ma son sospiri. Quivi sto io coi pargoli innocenti dai denti morsi de la morte avante che fosser da l’umana colpa essenti; quivi sto io con quei che le tre sante virtù non si vestiro, e sanza vizio conobber l’altre e seguir tutte quante. (Purg. 7.25-36)

Not for the having — but not having — done, I lost the sight that you desire, the Sun — that high Sun I was late in recognizing. There is a place below that only shadows — not torments — have assigned to sadness; there, lament is not an outcry, but a sigh. There I am with the infant innocents, those whom the teeth of death had seized before they were set free from human sinfulness; there I am with those souls who were not clothed in the three holy virtues — but who knew and followed after all the other virtues.

The above description of Virgilio as having sinned only through omission (“non fare”), not commission (“fare”) — “Non per far, ma per non fare” (Not for the having — but not having — done [Purg. 7.25]) — might have fully satisfied us before we encountered Cato in Purgatorio 1. But now have to contend in our minds with the question: if Cato can be saved, why not Virgilio?

The above description of Limbo is also noteworthy for giving equal attention to “innocent children” and “virtuous pagans”: here each of the two groups receives a terzina of description and the children are mentioned first. In comparison, in Inferno 4 the narrator pays no attention to the children other than to mention their existence in one word, telling us that he saw vast crowds “d’infanti e di femmine e di viri” (of infants and of women and of men [Inf. 4.30]).

Purgatorio 7.39, “là dove purgatorio ha dritto inizio” (“there where purgatory has its true beginning”) is Dante’s own language for what critics have labeled the distinction between “Ante-Purgatory” (a term Dante does not use) and “Purgatory proper”.

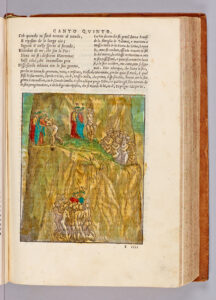

Nighttime has come: a time when the travelers might well “err” because climbing up the mountain is not possible without the light of the sun. Sordello therefore proposes to the travelers that they can pass the night safely in The Valley of the Princes and that he will be their guide to this safe haven.

In his Occitan poem, the planh (lament) for Blacatz (for which see Dante’s Poets, p. 156), the historical Sordello listed the various lords of Europe, whom he cites for their deficiencies in courage with respect to his dead lord, Blacatz. Similarly, the purgatorial Sordello now points out and comments on the various negligent princes who await purgation in the Valley.

There are various links between these princes and those who were so fiercely indicted one canto prior in Purgatorio 6. Here too Dante begins to delineate his theory of heredity, of what we can inherit from our parents (mostly from our fathers, in this telling). We note Sordello’s emphasis on the physical features of the princes, at times amusing: the “nasetto” or “small-nosed” prince of Purgatorio 7.103 versus “colui dal maschio naso” — he of “manly nose” — in Purgatorio 7.113 and the “nasuto” or “large-nosed” man of Purgatorio 7.124.

I am reminded of the novelist Paul Auster on the singularity of noses: “For Paul Auster, New York is ‘the singularity of each person’s nose’ on the subway” (“Let Us Count the Ways” in The New York Times of December 2, 2001).

The distinct noses of Purgatorio 7 play into the discussion of heredity and indirectly address issues regarding the construction of masculinity.

Physical characteristics notwithstanding, Dante’s theory of heredity is quite radical for his time in its insistence that nobility is not passed on from father to son:

Rade volte risurge per li rami l’umana probitate; e questo vole quei che la dà, perché da lui si chiami. (Purg. 121-23)

How seldom human worth ascends from branch to branch, and this is willed by Him who grants that gift, that one may pray to Him for it!

Dante had long been interested in this question, and had expounded at length on the nature of true nobility (“gentilezza”) in Book 4 of the Convivio. In the Commedia he does more than expound: he shows us how he views this matter by showing us fathers who are damned while their sons are saved. For instance, Frederick II is damned and his son Manfredi is saved, Guido da Montefeltro is damned and his son Bonconte is saved, and Ugolino della Gherardesca is damned and his grandson Nino Visconti is saved.

Return to top

Return to top