Paradiso 30 opens by conflating time and space.

To understand the passage that opens Paradiso 30, we have to begin with a premise that allows us to measure time by measuring space: if noon is 6,000 miles away, then sunrise must be 900 miles — about 1 hour — distant.

We can thereby take the opening passage of Paradiso 30, verses 1-15, to mean the following. As at about 1 hour before sunrise, the stars disappear one by one before the arrival of the sun, so — focusing now on verses 10-15 — the angelic choirs faded away from my sight, leaving only Beatrice:

Non altrimenti il triunfo che lude sempre dintorno al punto che mi vinse, parendo inchiuso da quel ch’elli ’nchiude, a poco a poco al mio veder si stinse: per che tornar con li occhi a Beatrice nulla vedere e amor mi costrinse. (Par. 30.10-15)

So did the triumph that forever plays around the Point that overcame me (Point that seems enclosed by that which It encloses) fade gradually from my sight, so that my seeing nothing else—and love—compelled my eyes to turn again to Beatrice.

The disappearance of the stars from the night sky before dawn is thus compared (“Non altrimenti” — “not otherwise” — in verse 10) to the disappearance of the angelic hierarchies around the point at their center. Of this point Dante writes that it overcame him: “mi vinse” in verse 11. He then defines it in a periphrasis as the point that “seems enclosed by that which it encloses”: “parendo inchiuso da quel ch’elli ’nchiude” (12). As I wrote in the Commento on Paradiso 28, where the vision of the fiery point first begins:

This point is both center and circumference, both the deep (Augustinian) within and the great (Aristotelian) without. It is the Enclosed that Encloses/the Enclosing that is Enclosed.

Returning to the “plot”, the vision of the universe that was presented in Paradiso 28, the vision of the angelic hierarchies as circles around a blazing point, now fades away. The result, in a reprise of the dynamic that has moved the plot of Paradiso so many times before, is that the pilgrim turns from the “new” vision that has faded to the “old” vision that has been there throughout this voyage: Beatrice.

The Paradiso peforms a dialectical dance of the gaze, which is in effect a performance of the new objects that interrupt the line of becoming on the journey of life, as told in the discussion of angelic non-memory of Paradiso 29. However, there is a caveat here: these new objects are always the original — “old” — object. In other words, the new object — the “novo obietto” of Par. 29.80 — is always the same: it is always Beatrice.

The Paradiso’s dance of the gaze around Beatrice is a way of claiming that, if an object is “new” enough — as Beatrice is defined a “cosa nova” in the canzone Donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore — , then that object remains present and undiminished, indeed enhanced by the passage of time. Beatrice in effect represents a very special kind of new object, one that is miraculous, one whose newness only waxes, never wanes.

This dance echoes the spiral looping of forward motion and nostalgic lapse that is the signature property of terza rima. (On the spiral of terza rima, see The Undivine Comedy, p. 25.) The “old” vision — Beatrice — has, as always in this dialectical dance, become new: even more beautiful than she was the last time that Dante looked at her. Her new and enhanced beauty, enhanced by and during the period in which Dante looked elsewhere, is enough to propel him upward. This dialectic, between the “old” vision of Beatrice and the various visions of the “new” glories of Paradise, is Paradiso’s version of “the poetics of the new”, which I analyze with respect to the beginning of Inferno in chapter 2 of The Undivine Comedy.

According to the dialectic described above, the newest new vision — the vision of the angelic hierarchies circling around the fiery point — fades, and the pilgrim’s eyes therefore return to Beatrice. However, in a sign that we are reaching the end of this great voyage, on this occasion the return of the pilgrim’s eyes to Beatrice is not followed by her articulation of the new dubbio that concerns him, or by her explanation of something that he has seen.

Rather, the poem jumps, and Dante here records his great final tribute to Beatrice: a very long and significant metapoetic passage that covers 20 verses (16-36) and that eventually modulates into Beatrice’s beginning to speak in verse 38.

Paradiso 30 is in many ways like the visionary canto Paradiso 23; both canti are rehearsals for the absolute finale, Paradiso 33. The metapoetic passage of canto 30 is reminiscent of the metapoetic passage in canto 23, where the poet first announces that “convien saltar lo sacrato poema, / come chi trova suo cammin riciso” (the sacred poem has to leap across, as does a man who finds his path cut off [Par. 23.62-63]). Similarly in Paradiso 30 the poet announces the cutting off of the narrative line that he has been following up to now, using a Latinism for “cut”, “preciso”, that rhymes with and is etymologically related to the earlier “riciso” in Paradiso 23.

Importantly, the past participle that Dante uses in Paradiso 29’s critical passage on the difference between angelic and human cognition, to describe the cutting of the line of sight, a cutting or interruption that does not occur for angels, is “interciso”: “però non hanno vedere interciso / da novo obietto” (so that their sight is never intercepted by a new object [Par. 29.79-80]). All three past participles — riciso, interciso, preciso — are based on the Latin caedere, “to cut”. All are precious Latinisms, unusual terms.

The first and the third of this sequence of past participles, riciso (Par. 23) and preciso (Par. 30), are explicitly applied to the narrative line, thus explicitly metapoetic. They are about the writing of the poem. The second past participle, interciso (Par. 29), is instead applied to the line of sight: the line of existence, the line of becoming. It is not metapoetic but existential. It is not about the cutting of the narrative line, but about an epistemological cutting: the way we learn and know is a process of interruption, as one event after another occurs and then is cut off.

By linking sequentially these three etymologically identical past participles, which moreover rhyme with one another, Dante is sharing with us his fundamental insight, the insight that structures the Commedia: he has written a poem in which the narrative line self-consciously and deliberately sets out to imitate the epistemological line, the existential line, the line of becoming. The recognition of this insight is the animating principle of The Undivine Comedy, first discussed on pp. 22-23.

The narrative line of the Commedia deliberately imitates the epistemological line of becoming in order to make manifest in the texture of the poem the way that temporality conditions all facets of our existence. Stated thus, that time conditions our existence is obvious and evident to all of us. But to make manifest in language the temporality of existence, and then to make manifest the attempt to escape the temporality of existence, as Dante does, is arduous and unique.

In the paraphrase that follows, it is noteworthy how the issue of human susceptibility to interruption and concetto diviso (Par. 29.81), as thematized in the discussion of angelic non-memory in Paradiso 29, is here explicitly applied by Dante to the writing of his poem.

From the first day (“Dal primo giorno” [28]) that he saw her face until this moment, nothing has ever succeeded in interrupting “the sequence of my song”, the pursuit of his poetry: “’l seguire al mio cantar” (30). Up until this point (“infino a questa vista” [29]), his song has prevailed; his pursuit of it has never been interrupted. But now his pursuit of Beatrice in poetry, his seguire (note the repetition of this infinitive, in verses 30 and 31), his songful segueing, has come to an inflection point: it must desist.

As earlier it behooved him to jump, now it behooves him to desist altogether. Where before he wrote “convien saltar lo sacrato poema” (Par. 23.62), now he writes “ma or convien che mio seguir desista” (but now I must desist from this pursuit [Par. 30.31]).

It is this sense of the ending that tinges these verses with an anxiety that was not present earlier, and that expresses itself in the double seguire: the insistence on the line, the long narrative path that extends back to the furthest recesses of the poet’s past, all the way back to the Vita Nuova and its “stilo de la sua loda”, echoed here in the “loda” of verse 17. In order to convey its compelling concern with textuality’s telos-driven linearity, encoded into the repeated “infino a” (up to the point that), the passage is best cited in full. I have put in bold words that most emphasize the sense of the ending:

Se quanto infino a qui di lei si dice fosse conchiuso tutto in una loda, poca sarebbe a fornir questa vice. La bellezza ch’io vidi si trasmoda non pur di là da noi, ma certo io credo che solo il suo fattor tutta la goda. Da questo passo vinto mi concedo più che già mai da punto di suo tema soprato fosse comico o tragedo: ché, come sole in viso che più trema, così lo rimembrar del dolce riso la mente mia da me medesmo scema. Dal primo giorno ch’i’ vidi il suo viso in questa vita, infino a questa vista, non m’è il seguire al mio cantar preciso; ma or convien che mio seguir desista più dietro a sua bellezza, poetando, come a l’ultimo suo ciascuno artista. Cotal qual io la lascio a maggior bando che quel de la mia tuba, che deduce l’ardüa sua matera terminando . . . (Par. 30.16-36)

If that which has been said of her so far were all contained within a single praise, it would be much too scant to serve me now. The loveliness I saw surpassed not only our human measure—and I think that, surely, only its Maker can enjoy it fully. I yield: I am defeated at this passage more than a comic or a tragic poet has ever been by a barrier in his theme; for like the sun that strikes the frailest eyes, so does the memory of her sweet smile deprive me of the use of my own mind. From that first day when, in this life, I saw her face, until I had this vision, no thing ever cut the sequence of my song, but now I must desist from this pursuit, in verses, of her loveliness, just as each artist who has reached his limit must. So she, in beauty (as I leave her to a herald that is greater than my trumpet, which nears the end of its hard theme) . . .

Much as the Commedia is the story of what Dante saw, it is also the story of the recounting of what Dante saw. And, although we have felt the arduousness of that recounting before — for instance in the acknowledgement at the beginning of Paradiso 25 that this poem has “made me lean through these long years” — never have we felt the longue durée of Dante’s heroic feat as in these verses of Paradiso 30.

After the poet’s interruption, Beatrice begins to speak and announces that they have left behind the Primum Mobile, the “maggior corpo” (matter’s largest sphere [39]), and have entered the “heaven that is pure light” (39). Her words are an extraordinary example of interwoven language, a miniaturized and distilled version of the Occitan technique of coblas capfinidas, in which the last word of a strophe is picked up in the first word of the next strophe. Here the last word of a verse becomes the first word of the next verse, spelling out luce/luce/amore/amore/letizia/letizia in a golden skein of shimmery language:

con atto e voce di spedito duce ricominciò: «Noi siamo usciti fore del maggior corpo al ciel ch’è pura luce: luce intellettual, piena d’amore; amor di vero ben, pien di letizia; letizia che trascende ogne dolzore.» (Par. 30.37-42)

and with the bearing of a guide whose work is done, she began again: “From matter's largest sphere, we now have reached the heaven of pure light, light of the intellect, light filled with love, love of true good, love filled with happiness, a happiness surpassing every sweetness.”

Here, as in Gabriel’s song in Paradiso 23, we have circulata melodia. Where Gabriel’s song was defined as “circulata melodia” by the poet in Paradiso 23.109, here I am embracing Dante’s terminology. What in Paradiso 23 Dante accomplished through enjambment, a common feature of Paradiso poetics, here Dante accomplishes with a spectacular one-off: the technique of coblas capfinidas technique is inserted into the textuality of Paradiso 30. These verses are a graphic and aural incarnation of head-tailed circularity, a textual Alpha and Omega that gathers the ongoing spiral of terza rima into a net of verbal unity.

Moreover, these circularized and circularizing verses have the effect of attenuating the linear hierarchy of intellect over love that was declared in Paradiso 28.

Beatrice now tells the pilgrim that here he will see both courts of heaven, one angelic and one human, and that he will see the latter, the blessed men and women of the “human court”, in the forms that they will possess at the Last Judgment. The stipulation that he is vouchsafed to see “l’una in quelli aspetti / che tu vedrai a l’ultima giustizia” (one of them wearing that same aspect which you will see again at Judgment Day [Par. 30.44-45]) is remarkable. Dante is here imagining that his vision will have a fullness beyond what is conceded to the blessed themselves before the end of time. Thus, the wish that the pilgrim expressed to Saint Benedict in Paradiso 22, where he begs “ch’io / ti veggia con imagine scoverta” (to let me see, unveiled, your human face [Par. 22.59-60]), will be fulfilled. Nor does Saint Benedict’s solemn promise of Paradiso 22.61-63 refer, as some puzzled commentators have suggested, just to himself.

What follows would be much easier to show you as a film of phantasmagoric visions, rather than to paraphrase in words. But Dante makes the effort to try to put what he saw into words, so let us try to follow him.

Dante now sees; he experiences wave after wave of visionary input. Hence the triple rhyme on “vidi” — “I saw” — in verses 95, 97, 99. Triple rhymes constitute a severe break with the ongoing rhythm of terza rima, and are very rare: other than the vidi/vidi/vidi rhyme of Paradiso 30, the poem offers only the four sets of Cristo rhymes in Paradiso and the deeply sarcastic triple rhyme on ammenda in the political diatribe against the royal house of France in Purgatorio 20 (verse 65 and following). The four sets of Cristo rhymes are located in: Paradiso 12.71 and following, Paradiso 14.104 and following, Paradiso 19.104 and following, and Paradiso 32.83 and following.

And so the sacred poem is forced to jump. A triple rhyme is itself a stasis in the rhyme-scheme of the poem that creates a rupture in the narrative line, forcing the poem to jump, “as one who finds his path cut off”: “come chi trova suo cammin riciso” (Par. 23.63). Paradiso 30 does just that, jumping not from simile to simile in the mode of Paradiso 23 but from vision to vision. The pilgrim sees “umbriferi prefazi” of the truth (shadow-bearing prefaces [78] of the truth), and the text leaps from one vision to the next, attempting to record some shadow of the prefaces that the pilgrim saw.

The pilgrim is swathed by a living light that gives him a power beyond his own (49-51), kindling in him the ability to see the Empyrean in a phantasmagoric sequence of dissolving images.

He sees light in the form of a river whose banks are clothed in gemlike flowers, and whose effulgence emits living sparks coursing between its shores and its depths:

e vidi lume in forma di rivera fulvido di fulgore, intra due rive dipinte di mirabil primavera. (Par. 30.61-63)

and I saw light that took a river’s form— light flashing, reddish-gold, between two banks painted with wonderful spring flowerings.

After the pilgrim rushes to the river’s banks like an infant desiring milk and drinks of it with his lashes (two imagistic replays of Paradiso 23, another visionary canto), the river appears to him transformed from a length into a circle:

e sì come di lei bevve la gronda de le palpebre mie, così mi parve di sua lunghezza divenuta tonda. (Par. 30.88-90)

But as my eyelids’ eaves drank of that wave, it seemed to me that it had changed its shape: no longer straight, that flow now formed a round.

Now the pilgrim sees the two courts of heaven made manifest, as the river’s sparks transform into angels and the riverbank’s flowers into saints:

così mi si cambiaro in maggior feste li fiori e le faville, sì ch’io vidi ambo le corti del ciel manifeste. (Par. 30.94-96)

so were the flowers and the sparks transformed, changing to such festivity before me that I saw—clearly—both of Heaven’s courts.

An apostrophe interrupts, causing the poem to jump to an exclamatory tercet in which the poet prays to the divine light itself for the power of language to express what he saw:

O isplendor di Dio, per cu’ io vidi l’alto trïunfo del regno verace, dammi virtù a dir com’ïo il vidi! (Par. 30.97-99)

O radiance of God, through which I saw the noble triumph of the true realm, give to me the power to speak of what I saw!

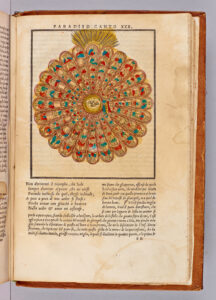

The narrator resumes: the light is distended in a circular shape (“in circular figura” [103]), around which rise the many tiers — more than a thousand (“più di mille soglie” [113]) — that seat the blessed. The whole is compared to a hillside mirrored in water at its base: “E come clivo in acqua di suo imo / si specchia” (And as a hill is mirrored in waters at its base [109–10]).

For the extraordinary build-up to the rose that follows, the jumping that characterizes the high Paradiso is more like a slide: like a baseball player sliding onto base unseen.

In the next terzina the image of a hill, expressed through simile (“come clivo”), jumps, becoming the vision of a rose, which suddenly appears without the warning of a preceding come (like). Not with the preparation of a simile, but with the immediacy of metaphor, suddenly the “clivo” of verse 109 slides, in verse 117, into manifesting itself as “questa rosa” (this rose).

The rose is repeated — “Nel giallo de la rosa sempiterna” (Into the yellow of the eternal Rose [124]) — before yielding in turn to the final vision, that of a city: “Vedi nostra città quant’ella gira” (See how much space our city’s circuit spans! [130]). The words “nostra città” signal the transition, by way of the empty throne that awaits Henry VII, into the final jump, which takes us to the political invective that closes Paradiso 30.

Beatrice’s last words deal with Dante’s grandiose political vision. Emperor Henry VII’s throne in Paradise awaits him (he died in 1313), because “he shall show Italy the righteous way — but when she is unready”: “a drizzare Italia / verrà in prima ch’ella sia disposta” (137-38). The future tense of the verb venire, “verrà” in verse 138, placed at the beginning of the verse, is reminiscent of the prophecy of the veltro in Inferno 1: “infin che ’l veltro / verrà” (until the Greyhound arrives [Inf. 1.101-02]).

Italy is “unready” for the arrival of the Emperor in part because of the machinations of the Pope, who does everything possible to thwart Henry VII. Dante is referring in verses 142-48 to Pope Clement V, mentioned in Inferno 19, in the bolgia of simony.

Beatrice’s last words in Paradiso 30, which are her last words in the Commedia, remark that Clement will not long be on the papal throne, because he will soon be in the bolgia where Simon Magus pays for his sins. Once arrived in the bolgia of simony, Clement will force “the one from Anagni” deeper into the earth:

Ma poco poi sarà da Dio sofferto nel santo officio; ch’el sarà detruso là dove Simon mago è per suo merto, e farà quel d’Alagna intrar più giuso. (Par. 30.145-48)

But God will not endure him long within the holy ministry: he shall be cast down there, where Simon Magus pays; he shall force the Anagnine deeper in his hole.

To me, even more stunning than Beatrice concluding her ministry by referring to Boniface VIII (who was born in Anagni, here “Alagna”) is that she concludes by intratextually buttressing the veracity of the vision of the Commedia. Her words very precisely characterize the punishment of the simonists as described in Inferno 19, where we learn that the sinners are stuck headfirst into holes, and pushed further down when someone new comes along. The intratextual moment is vertiginous, as this visionary canto ends with a very specific vision from the landscape of lower Hell, as witnessed and recorded by the author of the Commedia.

Return to top

Return to top