Brief Breakdown of Paradiso 1:

- 1-3 A statement of Paradiso’s guiding intellectual theme: the coexistence of unity and difference, the One and the Many

- 4-12 The poet, where he has gone and the difficulties of recounting what he has seen

- 13-36 Apostrophe to Apollo

- 37 The “story” begins: setting of time of year and place, the vernal equinox and the Earthly Paradise; Beatrice looks at the sun; Dante’s experience is like that of Glaucus; the coinage “trasumanar”; St. Paul’s raptus; more light and the pilgrim’s first expressed desire to know (“disio” in verse 83), a key plot driver of Paradiso; Beatrice solves the first doubt and generates a second: “ma ora ammiro / com’ io trascenda questi corpi levi” (But now I wonder how my body rises past these lighter bodies [Par. 1.98-99])

- 103-end Beatrice’s reply does not stoop to answer only the specific question, but goes back to first principles: the order of the universe, how all created being (the Many) returns to its Maker (the One)

The Commedia gets harder as you keep reading. Dante is quite explicit about the challenge that he poses to the reader in Paradiso: at the beginning of Paradiso 2, he tells the reader to turn back to shore, lest we get lost as we follow him onto the watery deep.

One of the difficulties of reading the Commedia is that as we go forward the textuality becomes more seamless, less divisible into nice narrative blocks. If you look at the Appendix on canto beginnings and endings in The Undivine Comedy, you will get an idea of how much harder it is to mark formal transitions in the second and especially the third cantica. In general, “plot” gets harder and harder to pinpoint. At the same time, we should make an effort to look for moments of “plot” in order to orient ourselves in what Dante himself will call, in the next canto, the “pelago” (ocean) of his text.

I offer a brief breakdown of Paradiso 1 into narrative units in order to aid navigation through the seamless pelago of text — the watery deep of poetry.

The first terzina of the Paradiso foregrounds “the paradox of più e meno”, as in the title of Chapter 8 of The Undivine Comedy: “Problems in Paradise: The Mimesis of Time and the Paradox of più e meno”. The paradox that Dante tackles is how “more” (“più”) and “less” (“meno”) — in other words, the reality of multiplicity, difference, the Many — can coexist with the One. I use “difference” as Dante uses it (“In astratto significa il ‘differire’ tra due o più elementi” [Fernando Salsano, Enciclopedia Dantesca, s.v. “differenza”]), and much as St. Thomas uses distinctio: “any type of non-identity between objects and things. Often called diversity or difference” (T. Gilby, Glossary, Summa Theologia, Blackfriars edition, 1967, vol. 8, p. 164). In other words, as is apparent from the discussion of time and difference in Chapter 8 of The Undivine Comedy, my usage is essentially Aristotelian.

In the opening three lines of the last cantica Dante offers two contrasting metaphysical realities. Verses 1 and 2 highlight the all-encompassing and borderless unity of the One who moves all and whose light penetrates the “universo” (a word whose etymology stresses oneness)[1]. His glory penetrates the universe, in other words it penetrates everywhere, and yet it shines “in one part more and in another less” (3):

La gloria di colui che tutto move per l’universo penetra, e risplende in una parte più e meno altrove. (Par. 1.1-3)

The glory of the One who moves all things permeates the universe and glows in one part more and in another less.

The prosaic third verse of the opening tercet, easily passed over when compared to the simple magnificence of its predecessors, is nonetheless crucial. Verse 3 introduces us to the irreducible reality of difference. The universe receives God’s light not equally, but differently, some parts receiving more and some parts receiving less: “in una parte più e meno altrove” (3). The first tercet is essentially a miniaturized creation discourse, the first of many that stud the first cantica, providing some of its most glorious poetry.

The theme of how the One and the Many — oneness and difference — coexist is the great theme of the Paradiso. This coexistence constitutes a paradox. It is the very paradox captured by Christian symbolism in the Trinity, which is both one and three. Dante’s meditation on this paradox will be our guiding thread through the arduous philosophical and theological problems that lie ahead, and through the difficulties of representation that beset the poet of the third realm.

* * *

At the beginning of Paradiso 1 we encounter the basic textual building blocks of Paradiso: moments of “plot” (what happened) are interspersed with the poet’s claims that he cannot recount what he saw — the “ineffability topos” — and with prayers and invocations for divine help in his arduous task. The textual building blocks are thus basically:

- sections of “plot”, what happened to the pilgrim; the moments are increasingly difficult to locate in the pelago of words

- plot also includes the long explanatory discourses that are offered by Beatrice and other souls whom the travelers meet

- various tropes that interrupt the narrative’s forward push and insist on the difficulty of the task: the ineffability topos (e.g. the poet telling us that there are no words for what he saw); prayers and invocations for assistance in recounting what he saw

These narrative elements are immediately present. The second terzina introduces plot by telling us that the narrator reached the highest heaven: “Nel ciel che più de la sua luce prende / fu’ io” (I was within the heaven that receives more of His light [Par. 1.4-5]). The same terzina also introduces the impossibility of recounting what he saw (“e vidi cose che ridire / né sa né può”):

Nel ciel che più de la sua luce prende fu’ io, e vidi cose che ridire né sa né può chi di là sù discende . . . (Par. 1.4-6)

I was within the heaven that receives more of His light; and I saw things that he who from that height descends, forgets or cannot speak . . .

The third terzina potently reminds us that the journey that we have been tracing in the Commedia is the journey of desire, and that it is the nearness of the goal that results in the failure of memory:

perché appressando sé al suo disire, nostro intelletto si profonda tanto, che dietro la memoria non può ire. (Par. 1.7-9)

for nearing its desired end, our intellect sinks into an abyss so deep that memory fails to follow it.

In the above terzina Dante also introduces us to another key trope of the Paradiso: the coniugatio of will and intellect. Let us consider the following question: Who or what approaches “its desire” in the phrase “appressando sé al suo disire”? Our intellect — “nostro intelletto” — is the answer. Our intellect, as it comes closer to its desire, plunges in so deeply that memory fails to follow. The intellect desires. And the desires of the intellect drive the plot of the Paradiso.

Prayers for help in this arduous poetic undertaking do not take long to follow. In Paradiso 1.15 we encounter the first of many prayers, in this instance to Apollo, to whom the poet turns for literal “in-spiration”: Dante uses the verb spirare here as he did in Purgatorio 24, where he defines himself as one who takes note when love breathes into him: “quando / Amor mi spira” (Purg. 24.52-53).

The invocation to Apollo introduces as well the first of many Ovidian analogies in the Paradiso, the canticle where the great Latin poet of change and transformation comes into his own. Here Dante refers gruesomely — reminding us of the linkage between vision and violence that I discussed with respect to the Ovidian dream of Purgatorio 9 — to Apollo’s “unsheathing” of Marsyas from his body, in a kind of terrible ec-stasis:

Entra nel petto mio, e spira tue sì come quando Marsia traesti de la vagina de le membra sue. (Par. 1.19-21)

Enter into my breast; within me breathe the very power you made manifest when you drew Marsyas out from his limbs’ sheath.

The story-line as we left it in Purgatorio 33 is resumed in Paradiso 1.37, where a lengthy astronomical periphrasis alerts us to the fact that, when Beatrice looks up at the sun in verse 46 of Paradiso 1, it is mid-day in Purgatory. In other words, when we begin the first canto of Paradiso, the pilgrim is “physically” still in Purgatory. This failure to execute a complete transition is markedly different from the transition between Inferno and Purgatorio.

The avoidance of a complete transition between Purgatorio 33 and Paradiso 1 reminds us that this universe is predicated on a binary between salvation and damnation, and that Purgatory is already the realm of the saved. In a fundamental way, then, Purgatory and Paradise are linked experiences, while Hell is utterly disjoined from them.

The avoidance of a complete transtition between Purgatorio 33 and Paradiso 1 also simulates, textually, the “thickness” and thus the seamlessness of reality — of being — that Dante more and more strives to conjure.

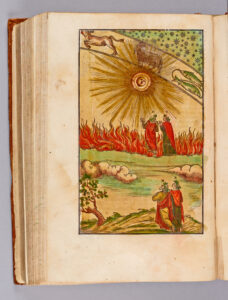

Let us return to plot. Beatrice looks up at the sun in verse 46. The pilgrim imitates his guide in verse 54 and looks up at the sun as well, which results in his seeing a doubling of light. He then looks back at Beatrice in verses 65-66.

This spiraling dialectic between Beatrice and everything else in Paradise will be fundamental to how things “happen” in Paradiso: vision is triggered by the dynamic whereby Dante first follows Beatrice in looking upward, then looks back at her, then looks upward again, and so on.

What happens now as a result of looking at Beatrice — “Nel suo aspetto tal dentro mi fei” (In watching her, within me I was changed [67]) — is that Dante experiences a transformation that takes him literally “beyond the human”: “trasumanar” (Par. 1.70). This extraordinary coinage, “tras” + “umanar” (a verb made from “umano”), signifies “to go beyond the human” and is typical of how Dante-author works in Paradiso.

Here, where Dante is trying to describe the indescribable, he does not simply give up. Rather, his inventiveness knows no bounds. In Paradiso therefore there will be many coinages. Dante will make new language.

And Dante will use Ovid. Here the “essemplo” — example, analogy — given by Dante to help us understand what it is to experience trasumanar is that of the fisherman Glaucus. In Ovid’s account in the Metamorphoses, Glaucus plunges into the sea upon eating the metamorphic herb that transforms him into a sea-god:

Nel suo aspetto tal dentro mi fei, qual si fé Glauco nel gustar de l’erba che ’l fé consorto in mar de li altri dèi. (Par. 1.67-69)

In watching her, within me I was changed as Glaucus changed, tasting the herb that made him a companion of the other sea gods.

This is the point at which Dante “leaves” Purgatory and “goes to” Paradise. You see what I mean about how you need to pay close attention to finding the “plot” in Paradiso.

Does he go in the body or not in the body? St. Paul, Dante’s biblical model for raptus (again, see Purgatorio 9), states the question in this way:

Scio hominem in Christo ante annos quatuordecim, sive in corpore nescio, sive extra corpus nescio, Deus scit, raptum huiusmodi usque ad tertium caelum (2 Cor. 12:2)

I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago (whether it was in the body or out of the body I do not know—God knows) was caught up to the third heaven.

Dante echoes St. Paul:

S’i’ era sol di me quel che creasti novellamente, amor che ’l ciel governi, tu ’l sai, che col tuo lume mi levasti. (Par. 1.73-75)

Whether I only was the part of me that You created last, You — governing the heavens — know: it was Your light that raised me.

Dante makes evident throughout the Commedia that he took his extraordinary journey in the most extraordinary way — in the flesh. In the above verses he is is not recanting, but simply expressing his radical claim in the veiled and Pauline manner adopted by his biblical predecessor: “Dante is deliberately following his avowed and greatest model, St. Paul, whose ambiguity regarding the corporeality of his raptus did not prevent the early Church fathers from viewing it as a real event” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 148; Chapter 7 of The Undivine Comedy discusses this issue in great detail).

Dante does not understand what has occurred, and Beatrice explains: “Tu non se’ in terra, sì come tu credi” (You are not on the earth as you believe [Par. 1.91]). We notice the charmingly simple nature of her reply, as if speaking to a child, for whom very short and simple words are required. Her explanation only provokes more curiosity: how is it possible that he has risen above these light bodies, the spheres of air and fire (Par. 1.97-99)?

Frequently, the narrative rhythm of the Paradiso will involve the following dynamic. The pilgrim poses a question that could be answered locally and succinctly. Instead it is taken as an opportunity for the poet, in the voice of the pilgrim’s interlocutor, to take a deep breath, take a long step back, and deal with the explanation not at the local level but starting from first principles.

This dynamic now comes into play, as Beatrice takes Dante’s question as an opportunity to explain the order of the universe, how all created beings return to their individual “ports” in the “great sea of being”: “lo gran mar de l’essere” (Par. 1.113). According to this cosmic order, Dante’s rising is not remarkable; rather, it would be remarkable if he were not to rise, now that he is free of all impediment (Par. 1.139-40).

In The Undivine Comedy I discuss the surpassing difficulty of expressing unity and oneness and simultaneity through language, a medium that is differential and time-bound and linear. Already in this first canto of Paradiso we see some of Dante’s strategies. These strategies are, in that he is a writer, by necessity ultimately linguistic. They depend on a poetic virtuosity that he pushes to remarkable limits.

Dante has at his command singular resources of metaphoric language: only metaphor is able to placate the tension between the one and the many. The great ontological metaphor of the “gran mar de l’essere” in which the più and the meno of creation is all embraced, each at its own proper port, is an example of the kind of metaphoric language that Dante will use to express the oneness of creation.

The metaphor of the universe as a “great sea of being” — “gran mar de l’essere” — was anticipated, textually, by the Ovidian example of Glaucus, who became “consorto in mar de li altri dèi”: consort in the sea of the other gods (Par. 1.69). For Dante, the word “corsorte” has its full etymological sense of one who shares a destiny (“con” = with + “sorte” = destiny, from Latin “sors”), thus becoming like the being with whom a destiny is shared.

The sea does for Glaucus what the great sea of being does for the various differentiated forms of being that find their various ports in the all-embracing oneness of the metaphorical sea/universe. The sea is the unifying medium that absorbs Glaucus and renders him similar to the other gods, their “con-sort” in the waters of being, alike to them in his sorte, no longer different. Hence to become “consort in the sea of the other gods” is to become divine. What has been described is a process of going beyond the human (“trasumanar”) and becoming godlike.

[1] Universe = “the whole world, cosmos,” from Old French univers (12c.), from Latin universum “the universe,” noun use of neuter of adj. universus “all together,” literally “turned into one,” from unus “one” + versus, past participle of vertere “to turn”.

Return to top

Return to top