[1] We are still on the terrace of wrath, which began in Purgatorio 15 with the examples of the virtue of meekness or gentleness (the virtue that corresponds to the vice of wrath). Purgatorio 17 begins with a dramatic two-pronged apostrophe. First Dante addresses the reader — a dramatic event in itself, for this is the only address to the reader in the exordium of a canto. Dante then addresses our imaginative faculty or power of imagination. The poet asks the reader — you and me — if ever we had the experience of being caught in a fog in the mountains, to remember what it was like when the vapors begin to melt and the sun to shine through (Purg. 16.1-12). Dante-poet is describing the dissipation of the black fog that envelops the terrace of anger, as Dante-pilgrim and Virgilio leave the third terrace behind.

[2] The evocative recall of a mountain experience — “Ricorditi, lettor, se mai ne l’alpe (Remember, reader, if ever in the mountains [Purg. 17.1]) — is a leitmotif of Dante’s imagination. I’m thinking of his extraordinary canzone Amor, da che convien pur ch’io mi doglia, likely written circa 1306 when the poet was in the mountainous Casentino area, whose congedo begins: “O montanina mia canzon, tu, vai” (My mountain song, go your way [Amor, da che convien, 76]).

The apostrophe to the imagination (Purg. 17.13-18) is a meditation on the relationship between what we can imagine and our sense perception: can we imagine only that which we experience through our senses? This is an extraordinarily important point, especially for a poet who records mystical experiences and who was simultaneously a committed realist and a committed Aristotelian. The question posed to the imaginativa — “chi move te, se ’l senso non ti porge?” (who moves you when the senses do not spur you? [Purg. 17.16]) — is of enormous relevance to understanding how Dante understood the imaginative act that resulted in his own creation: this simultaneously mystical and realistic poem, the Divina Commedia.

The examples of the vice of anger follow, experienced by the pilgrim as ecstatic visions. Again, the way in which these visions are represented is of great relevance to thinking through how Dante thinks about the problems inherent in representing visionary experience. As discussed in the Commento on Purgatorio 15, vis-à-vis the ecstatic visions that are there called by the poet “non falsi errori” (nonfalse errors [Purg. 15.117]), these ecstatic visions are the micro-vision analogues to the macro-vision that is this poem.

Next is the final section of the terrace of anger: the encounter with the angel, the recital of the Beatitude, the removal of the “P” from Dante’s brow, and the climb to the next terrace. The travelers have reached the top of the stairs but cannot proceed to the next terrace; the sun has set, and the pilgrim is becalmed like a ship that has reached the shore. While perforce unable to move on to the “new things that his eyes desire” (“novitadi ond’e’ son vaghi” [Purg. 10.104]), the pilgrim slakes his curiosity (his insatiable curiosity, like that of Kipling’s Elephant’s Child) by asking Virgilio to tell him about what lies ahead: “quale offensione / si purga qui nel giro dove semo?” (what offense is purged within the circle we have reached? [Purg. 17.82-83]).

Although the pilgrim’s query is restricted to the next terrace, Virgilio takes an expansive route in his reply, offering the purgatorial equivalent of Inferno 11. There, while adjusting their olfactory senses to the stench wafting out of the abyss, Virgilio explained the moral structure of Hell. Here, while waiting for the sun to rise, Virgilio explains the moral structure of Purgatory.

We learned in Inferno 11 that Dante bases the moral structure of Hell on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. We also learned in Inferno 11 that the circles of Hell prior to arriving at the city of Dis hold sinners guilty of “incontinence” (“incontenenza” in Inf. 11.82 and 83): those who lacked moderation and self-control, who desired immoderately and excessively. Once we have read Inferno 11 we have a better understanding of why Inferno 7 contains not just misers but misers and prodigals: Dante is not, after all, following the system of the seven capital vices in Hell. Dante is using Aristotle’s system, whereby, with respect to avarice, the virtue (liberality) is the mean between the vices of avarice and prodigality.

But what happens if we try to apply the idea of “incontenenza” to the other sins of upper Hell? The presence of souls carrying within themselves an “accidioso fummo” (slothful smoke [Inf. 7.123]), submerged in the Styx below the wrathful, suggests the possibility of an Aristotelian understanding of anger in Hell, with sloth (accidia) at one extreme, anger (ira) at the other extreme, and righteous anger as the virtuous mean. We certainly see many signs of anger formulated according to the doctrine of the mean in Purgatory. The idea of a righteous versus a non-righteous wrath is embedded in Nino Visconti’s “dritto zelo / che misuratamente in core avvampa” (righteous anger that burns with misura in the heart [Purg. 8.83–84]). Even the Beatitude that marks the departure from the terrace of wrath is formulated according to the doctrine of the mean: “Beati / pacifici, che son sanz’ ira mala!” (Beati pacifici, who are without sinful wrath [Purg. 17.68–69]). The phrase “evil anger” — “ira mala” in Purgatorio 17.69 — with its implied counterpart, “good anger” or “ira buona”, rewrites the Beatitude. In this way Dante works to align the Bible with the more Aristotelian idea of a measured wrath, as previously encountered in Giudice Nin’s “dritto zelo” (zelo is always positive in the Commedia; see also “buon zelo” in Purgatorio 29.23 and Paradiso 22.9).

With respect to the lustful, however, Inferno offers only one kind of lack of misura; there is no insufficient love punished in the second circle of Hell. For that idea we have to await Purgatorio. In the second realm, based on the Christian system of the seven capital vices, Dante finds a way of superimposing the Aristotelian idea of continence/incontinence (in vernacular terms: misura and dismisura) through the idea of loving with too much vigor and with too little.

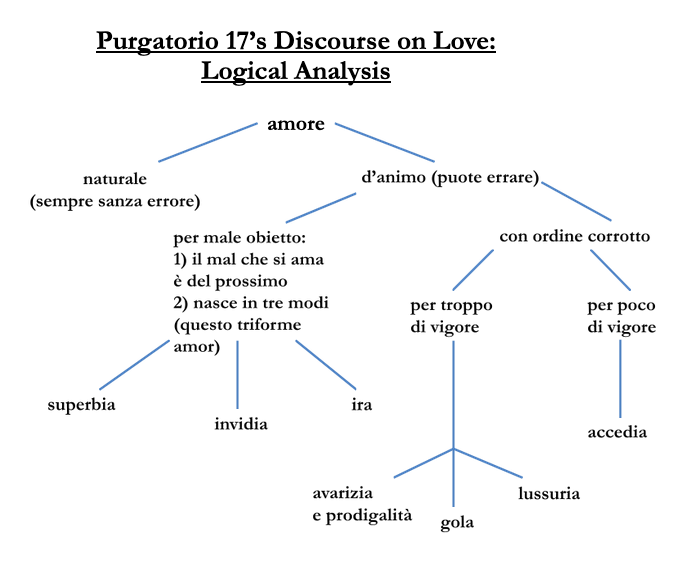

Virgilio proceeds by distinctions, breaking down love in such a way as to enable it to account for everything we do. I will follow Virgilio’s distinctions and gloss them in the subsequent analysis. Here is an overview of what we will be discussing in a chart that distills the logical argument of Virgilio’s discourse:

First he distinguishes between natural love that cannot err, instilled in us, which he puts aside for the purpose of his analysis, turning rather to elective love, which can err in three possible ways. Elective love can choose an evil object, it can love with too little vigor, or it can love with too much vigor:

Lo naturale è sempre sanza errore, ma l’altro puote errar per malo obietto o per troppo o per poco di vigore. (Purg. 17.94-96)

The natural is always without error, but mental love may choose an evil object or err through too much or too little vigor.

Love for the wrong object will express itself in pride, envy, and anger: these are the vices purged on the lower three terraces of Purgatory. Love for the right object that is expressed with insufficient vigor is sloth or accidia: this is the vice purged on the fourth terrace. Love for the right object that is expressed with excessive vigor is purged on the top three terraces; such love takes the form of avarice, gluttony, and lust. The seven capital vices therefore are distorted forms of love.

In effect, this division is not tripartite, for there are two basic modalities for loving in the wrong way. The first way, as we have seen, is to love the wrong object. After eliminating the possibility that loving the wrong object can involve the self or God, Dante settles on loving the wrong object with respect to one’s neighbor: “’l mal che s’ama è del prossimo” (ill love must mean to wish one’s neighbor ill [Purg. 17.113]). In this way, the category of loving the wrong object is not about the self in a vacuum in Dante’s analysis. Rather, it paves the way for an analysis of the self in its dealings with the other, and a meditation on the golden rule, which is violated in Dante’s definitions of pride, envy, and anger.

If the first large category in Virgilio’s analysis is love of the wrong object, the second category is love of the right object that expresses itself in the wrong way: “o per troppo o per poco di vigore” (with too much or too little vigor [Purg. 17.96]). In this way, we see that the two categories are love of the wrong object and love of the right object incorrectly expressed.

It is the second of these two categories that captures Dante’s imagination more fully.

Another important corollary to this analysis is: all our actions stem from love. Whatever we do, good or bad, is motivated by love:

Quinci comprender puoi ch’esser convene amor sementa in voi d’ogne virtute e d’ogne operazion che merta pene. (Purg. 17.103-05)

From this you see that—of necessity— love is the seed in you of every virtue and of all acts deserving punishment.

I have emphasized Aristotle in this commentary, because I am fascinated by Dante’s attempts throughout the Commedia to suture the non-binary system of the Greek philosopher onto the Christian binary system, one that is fundamentally Augustinian. Augustine provides the language of bonus amor versus malus amor: “a right will is good love and a wrong will is bad love” (“recta itaque voluntas est bonus amor et voluntas perversa malus amor”), he writes in City of God 14.7.

The idea that all our behavior is rooted in love takes us to Aquinas’s treatise on the passions, which contains a precept frequently cited by commentaries on Purgatorio 17: “Unde manifestum est quod omne agens, quodcumque sit, agit quamcumque actionem ex aliquo amore” (every agent whatsoever, therefore, performs every action out of love of some kind [ST 1a2ae.28.6; Blackfriars 1967, vol. 19, pp. 106–07]). While cited in commentaries on this canto, it seems to me that we do not take Aquinas’s words seriously enough. If we are to take seriously Dante’s insistence that all behavior is rooted in love then we have to consider extending this challenging idea in a more systematic way to our reading of Inferno. For instance, I tried to apply this principle to Inferno 10 in “Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell,” where I discuss from this perspective the love of Farinata for Florence and of Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti for his son Guido.

Return to top

Return to top