I will begin with the verses in Paradiso 29 that are foundational for the analysis carried out in The Undivine Comedy. My reading is based on an analogy between the story that Dante describes — his journey through the afterworld and his meeting with “le vite spiritali ad una ad una” (the lives of spirits, one by one [Par. 33.24]) — and the narrative that recounts that journey. Dante’s narrative, like all narrative and indeed like all language, is subject to time and is a manifestation of human cognition. Human cognition, as we learn in Paradiso 29, is differentiated thought, literally divided thought: “concetto diviso” (Par. 29.81).

As Chiavacci Leonardi notes, “diviso” in “concetto diviso” means “suddiviso dal tempo”: divided by time, therefore sequential, discursive, not circularized, not unified. Divided by time as, in fact, all language, all narrative, all human thought, all human cognition, inevitably are. Dante has taken the opportunity of discussing angelic memory to define human thought in opposition to angelic thought.

The pilgrim’s journey is a linear path interrupted by encounters with new things, a path on which the pilgrim encounters the new one by one, precisely as we do in life: “le vite spiritali ad una ad una” (the lives of spirits, one by one [Par. 33.24]). The pilgrim’s path is in fact, as we now learn, a mirror of how Dante conceptualizes human experience: Dante conceptualizes human experience as a linear path affording encounters with the new, a line of becoming intercepted by newness.

We can extrapolate Dante’s understanding of human experience from Dante’s treatment of the topic of angelic memory in Paradiso 29.

Dante treats angels and their lack of need for memory in such a way as to offer a clear description — by contrast — of human cognition. By defining angelic cognition, he lets us know what human cognition is not. Because angels never turn their gazes from the face of God and see all things in His eternal present, their sight is uninterrupted by new things, and they have no need of memory (which we use to store the new things once they are no longer new):

Queste sustanze, poi che fur gioconde de la faccia di Dio, non volser viso da essa, da cui nulla si nasconde: però non hanno vedere interciso da novo obietto, e però non bisogna rememorar per concetto diviso . . . (Par. 29.76-81)

These beings, since they first were gladdened by the face of God, from which no thing is hidden, have never turned their vision from that face, so that their sight is never intercepted by a new object, and they have no need to recollect an interrupted concept.

The steps in the argument are:

- Angels never turn their gaze from the face of God, in Whom they see all things.

- Therefore, angels “non hanno vedere interciso / da novo obietto” (79-80): their sight is never intercepted by a new object that comes along the line of becoming. Indeed, for angels, there IS no line of becoming!

- A further corollary of uninterrupted angelic sight — the fact that they always see everything all at once by gazing at the Transcendent — is that angels have no memory. Angels have no memory because they have no need to remember, given that remembering is a product of differentiated cognition: “e però non bisogna / rememorar per concetto diviso” (and therefore there is no need to remember by way of divided thought [Par. 29.80-81]).

In sum, everything is manifest to angels at the same time in God. Hence there is no line of becoming that can be interrupted, hence memory is superfluous, not needed.

However, in telling us that angels do not need memory, Dante goes further. He also tells us WHY they do not need memory. And he further stipulates the process that angels do not need: namely, the process of differentiated thought. Angels do not need memory because their sight is not interrupted and therefore they do not need to remember by way of a differentiated thought process: “e però non bisogna / rememorar per concetto diviso” (and therefore there is no need to remember by way of divided thought [Par. 29.80-81]).

Dante thus concludes this passage on angelic memory with a turn toward the human — toward human concetto diviso. In doing so, he is telling us not only why angels do not need memory, but why humans do. Humans need memory in order to store the new objects once they are no longer new. The line of becoming intercepted by new objects recedes into the past, but we keep it in our memories.

Aquinas is very helpful with respect to the difference between human cognitive processes and those of angels. He poses the questions “does an angel know by discursive thinking” (“utrum angelus cognoscat discurrendo” [ST 1a.58.3]) and “does an angel know by distinguishing and combining concepts” (“utrum angeli intelligant componendo et dividendo” [ST 1a.58.4]). He points out that angels acquire knowledge intellectually, by intuiting first principles, whereas humans acquire knowledge rationally, through a discursive process: “Discursive thinking implies a sort of movement, and all movement is from a first point to a second one distinct from it” (“discursus quendam motum nominat. Omnis autem motus est de uno priori in aliud posterius” [ST 1a.58.3 ad. 1]),. Likewise, “just as an angel does not understand discursively, by syllogisms, so he does not understand by combining and distinguishing . . . For he sees manifold things in a simple way” (“Nihilominus tamen compositionem et divisionem enuntiationum intelligit, sicut et ratiocinationem syllogismorum, intelligit enim composita simpliciter” [ST 1a.58.4 co.]).

Aquinas’s “discursive thinking” is Dante’s “concetto diviso” of Paradiso 29.81. With respect to humans, we can extrapolate an understanding of our human cognitive processes as the contrary of those of angels who — as Aquinas explains — do not think discursively but intuit from first principles.

Our sight is constantly cut off — “interciso” in verse 79 — by new things along the path. We remember the pilgrim in Purgatorio 10, whose eyes so long for “novitadi” — newness — that he is happy to turn his gaze when so instructed by Virgilio:

Li occhi miei ch’a mirare eran contenti per veder novitadi ond’e’ son vaghi, volgendosi ver’ lui non furon lenti. (Purg. 10.103-05)

My eyes, which had been satisfied in seeking new sights—a thing for which they long— did not delay in turning toward him.

The “novo obietto” of Paradiso 29.80 requires a mental structure that can accommodate it, and so humans have “concetto diviso”: divided thought, discursive thinking, sequential thinking. Since we do not see everything all at once, but must see and remember many new things sequentially, “ad una ad una” (as in “le vite spiritali ad una ad una” of Paradiso 33.24), we think differentiatedly, discursively, sequentially, by way of divided thoughts: “per concetto diviso”.

The above passage from Paradiso 29 is featured at the beginning of Chapter 2 of The Undivine Comedy, “Infernal Incipits: The Poetics of the New,” because it is the basis for understanding Dante’s “poetics of the new”, and thus the foundation of my analysis:

The poem’s narrative journey, like the pilgrim’s represented journey, is predicated on a principle of sequentiality, on encounters that occur one by one, “ad una ad una,” in which each new event displaces the one that precedes it. Like all narrative (indeed like all language), but more self-consciously than most, the Commedia is informed by a poetics of the new, a poetics of time, its narrative structured like a voyage in which the traveler is continually waylaid by the new things that cross his path. Life is just such a voyage: it is the “nuovo e mai non fatto cammino di questa vita” (“new and never before traveled path of this life” [Conv. 4.12.15]), in which our forward progress is articulated by our successive encounters with the new.

(The Undivine Comedy, p. 22)

One more corollary is raised by Dante’s treatment of angels’ lack of need for memory, and his subsequent definition of human cognition in opposition to angelic cognition: “e però non bisogna / rememorar per concetto diviso” (they have no need to remember by way of divided thought [Par. 29.80-81]). Dante’s turn toward the human concetto diviso throws light on the poema sacro, which only exists because humans remember and think discursively. Angels do not need to write, which humans do for the purpose of memorializing what we invent and make and do. Consequently, angels do not create poetry. Only humans do.

***

The opening simile of Paradiso 29 is worth paying close attention to, even though difficult. Dante describes the brief moment in which Beatrice pauses in her speech as like the moment in time when sun and moon are equidistant and perfectly poised on the horizon, before one moves up and the other down. We should pay attention to the word “punto”: in verse 4 the noun is used for a point of time, in verse 9 the noun refers to a point of space, and in verse 12 we find a conflation of time and space in the verb appuntare, used in a periphrasis for God. God is There Where All Wheres and all Whens Converge, in a point: “là ’ve s’appunta ogni ubi e ogni quando” (where, in a point, all wheres and whens end [Par. 29.12]).

Beatrice now discourses on creation, a theme that we find also in Paradiso 1, 2, 7, and 13. It is difficult for me to say which is my favorite creation discourse of Paradiso. These passages are all special, and contain some of the most sublime poetry of the third cantica.

The creation discourse of Paradiso 29 is remarkable among creation discourses, for a variety of reasons. fn Paradiso 29 Dante writes not, in more familiar terms, of God’s generosity in creating multiplicity. Rather, with the sublime cadenza that marks his greatest metaphysical verse (we think, for instance, of Paradiso 13’s “Ciò che non more e ciò che può morire” [52]), Dante represents the act of creation as an opening:

Non per aver a sé di bene acquisto, ch’esser non può, ma perché suo splendore potesse, risplendendo, dir “Subsisto”, in sua etternità di tempo fore, fuor d’ogne altro comprender, come i piacque, s’aperse in nuovi amor l’etterno amore. (Par. 29.13-18)

Not to acquire new goodness for Himself— which cannot be—but that his splendor might, as it shines back to Him, declare “Subsisto,” in His eternity outside of time, beyond all other borders, as pleased Him, Eternal Love opened into new loves.

The extraordinary verse “s’aperse in nuovi amor l’etterno amore” (Eternal love opened into new loves [Par. 29.18]) holds in balance the “new loves” and the “Eternal love”. Here we find in nuce the whole problematic of the novo. Although the “nuovi amor” of Paradiso 29 are positively charged, as the products of God’s divine self-opening, we remember the creation discourse of Paradiso 7, where the new is negatively charged. There we learned that the heavens are “new things”, and that to be free is not to be subject to “the power of the new things”: “la virtute de le cose nove” (Par. 7.72).

How, and more importantly why, the eternal should give rise to the corruptible, the One should make way for the Many, is the question posed in the dialectic between l’etterno amore and nuovi amori. In the contrast between the eternal love and the new loves that it generates is all the splendor and pathos of created existence.

God’s creation is timeless, immune from the difference that characterizes all human actions, movements, and discourses. God creates “in sua etternità di tempo fore” (in His eternity outside of time [Par. 29.16]). His act of creation is preceded by no Before. For there is neither “before” nor “after” with respect to divine creativity:

Né prima quasi torpente si giacque; ché né prima né poscia procedette lo discorrer di Dio sovra quest’acque. (Par. 29.19-21)

Nor did he lie, before this, as if languid; there was no after, no before—they were not there until God moved upon these waters.

The phrase ”né prima né poscia” echoes Dante’s Italian rendering of Aristotle’s definition of time in the Convivio:

Lo tempo, secondo che dice Aristotile nel quarto de la Fisica, è “numero di movimento, secondo prima e poi”; e “numero di movimento celestiale”, lo quale dispone le cose di qua giù diversamente a ricevere alcuna informazione. (Conv. 4.2.6)

Time, as Aristotle says in the fourth book of the Physics, is “number of motion with respect to before and after,” and “number of celestial movement” is that which disposes things here below to receive the informing powers diversely. (Lansing trans.)

“For time is just this,” writes Aristotle, “number of motion in respect of ‘before’ and ‘after’” (Physics 4.11.219b1; ed. McKeon 1941): “numerus motus secundum prius et posterius” (Physica, Aristoteles Latinus Database). To say that there is no “before” or “after” with respect to God is therefore to repeat the information of God’s out-of-timeness from verse 16: God exists “in sua etternità di tempo fore” (in His eternity outside of time [Par. 29.16]).

The stress on God’s out-of-timeness continues in the next step of creation, which occurs without any interval and without any ditinction. The triple creation of form, matter, and their union knows no interval between inception and fulfillment — “che dal venire / a l’esser tutto non è intervallo” (from its coming to its being there is no interval [Par. 29.26-27]) — but takes its being all together and at once: “sanza distinzïone in essordire” (with no distinction in beginning [30]).

Both Paradiso 28 and 29 are devoted to angelic intelligences, and thus, beginning in Paradiso 29.37, the creation discourse turns to the creation of angels. Beatrice moves, so to speak, into the topic of angelic “history”: here Beatrice treats the fall of Lucifer (from verse 55) and the grace/merit formula that applies to the virtuous angels. The question comes up, in verse 70, of those philosophers who mistake angelic nature, and Beatrice takes the opportunity to clarify that angels do not have memory, and why, in the verses that I discussed at the opening of this commentary (76-81).

The tone turns polemical in verse 82, and Beatrice moves into a condemnation of those preachers who instead of following Scripture go about inventing anything they want. Such preachers even lie (“e mente” in verse 100 = “and he lies”). Here we have the worst of human creativity. The best of human creativity — in stark contrast to the mendaciously inventive preachers — is poetry, philosophy, art: all the great products of human invention. One instance is the poetic work that we are reading and that Dante wrote: the teodìa that required all the poet’s resources of memory and of concetto diviso to create.

Thus, the negative inventions of the mendacious preachers brings the poet back to the issue at the core of this canto: memory, concetto diviso, and what humans do with them. There is a strong link between this issue and the treatment of language as a product of human pleasure in creation at the end of Paradiso 26.

In verse 127, Beatrice notes that she has digressed (the only other reference to digression is another hugely polemical moment, Purgatorio 6), and comes back to the topic of angelic nature. She concludes with a sublime restatement of the paradox of their difference/unity:

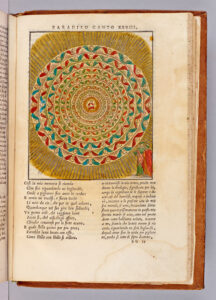

Vedi l’eccelso omai e la larghezza de l’etterno valor, poscia che tanti speculi fatti s’ha in che si spezza, uno manendo in sé come davanti. (Par. 29.142-45)

By now you see the height, you see the breadth, of the Eternal Goodness: It has made so many mirrors, which divide Its light, but, as before, Its own Self still is One.

Return to top

Return to top