- “Dante’s poetic mission: at the beginning of Inferno 32 he draws on his early canzone Così nel mio parlar vogli’esser aspro (one of the rime petrose, circa 1296) to articulate his poetic credo, which is based on the principle of mimesis

- along with the metapoetic diction borrowed from the early canzone, Dante transfers other specific features of Così nel mio parlar to Inferno 32: one such feature is hair-pulling, which Dante shifts from a sexualized and gendered domain to a desexualized and political domain

- the “weather” of Inferno 32 also hails from the lyric tradition: winter is a trope of the lyric tradition (the self is “wintry” and dead while the rest of creation participates in the warm springtime of reciprocated love); now the winter trope furnishes the ambience of the pit of Hell

- ice: the frozen core — the frozen heart — at the wintry center of the universe

- ice: a mirror of the self

- the lack of a clear demarcation between family betrayal and political betrayal: this ambiguous boundary anticipates the Ugolino episode of Inferno 32-Inferno 33

- there are significant connections between the traitors of circle 9 and the lustful sinners Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta of circle 2 (Inferno 5): “Caina” is named in Inf. 5.107 as the future home of Gianciotto Malatesta; moreover, as I noted in “Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender” (cited in Coordinated Reading), after killing his adulterous wife, the uxoricide-widower Gianciotto Malatesta married Zambrasina de’ Zambrasi, the daughter of Tebaldello de’ Zambrasi of Faenza, who resides among the traiters in circle 9

- the theme of the “bestial segno” and the utter distortion of language: here language is used not to comfort and to console and to communicate — language is used to betray

[1] As is usual for Dante, acknowledgment of radical representational inadequacy reinforces his dedication to overcome such lack, to be “di natura buona scimia” (Inf. 29.139): a “good ape of nature”, in other words, a great mimetic artist. He seeks to find the language that will eliminate difference, traversing the gap between what De vulgari eloquentia calls the rational and the sensual aspects of language (Dve 1.3.2): the gap between the meaning and the sound, between the signified and signifier. In the formulation of Inferno 32.12, this is the gap between the “fatto” (the “fact” or the real event as it occurred) and the “dir” (the word that signifies that event): “sì che dal fatto il dir non sia diverso” (so that my word not differ from the fact [Inf. 32.12]).

[2] The goal is to achieve a language (“dir”) that is indivisible — that is not divergent (“diverso”) — from reality (“fatto”): “sì che dal fatto il dir non sia diverso” (Inf. 32.12). The dir must not differ from the fatto that the dir represents. Accordingly, the great cascade of metapoetic language that opens Inferno 32 celebrates the heroic quest of Dantean mimesis:

S’io avessi le rime aspre e chiocce, come si converrebbe al tristo buco sovra ’l qual pontan tutte l’altre rocce, io premerei di mio concetto il suco più pienamente; ma perch’ io non l’abbo, non sanza tema a dicer mi conduco; ché non è impresa da pigliare a gabbo discriver fondo a tutto l’universo, né da lingua che chiami mamma o babbo. Ma quelle donne aiutino il mio verso ch’aiutaro Anfïone a chiuder Tebe, sì che dal fatto il dir non sia diverso. (Inf. 32.1-12)

Had I the crude and scrannel rhymes to suit the melancholy hole upon which all the other circling crags converge and rest, the juice of my conception would be pressed more fully; but because I feel their lack, I bring myself to speak, yet speak in fear; for it is not a task to take in jest, to show the base of all the universe — nor for a tongue that cries out, “mama,” “papa”. But may those ladies now sustain my verse who helped Amphion when he walled up Thebes, so that my tale non differ from the fact.

[3] Because we humans exist in time, and because our representation of life always comes into existence belatedly with respect to life itself, Dante’s quest is an impossible one: it is an “ovra inconsummabile” or “unaccomplishable task” (Par. 26.125), in the phrase used by Adam for the Tower of Babel. Nonetheless, the ovra inconsummabile of creating a language in which dir is not different from fatto — an “impresa” (Inf. 32.7) undertaken with full understanding of the reasons that make it impossible — is the heroic quest of the Commedia. In my opinion, Dante accomplishes this Ulyssean quest, this ovra inconsummabile, as well as any person who has ever lived.

[4] As we have seen, Inferno 32 begins with an extraordinary metapoetic opening. This opening passage includes an invocation to the Muses and also echoes Dante’s own erotic canzone Così nel mio parlar vogli’esser aspro (written circa 1296). This canzone, one of the four so-called rime petrose (“stony rhymes”), itself boasts a metapoetic opening, in which Dante writes about the desire to find a poetic form that is fully commensurate with his content. The canzone’s content centers on a woman who is presented in verse 2 as a beautiful stone (“questa bella pietra”), and whose actions (“atti”) are cold, harsh, and unyielding. Consequently the poet seeks language (“parlar”) that is as harsh (“aspro”) as is the lady in her treatment of him:

Così nel mio parlar vogli’esser aspro com’è negli atti questa bella pietra . . . (Così nel mio parlar, 1-2)

I want to be as harsh in my speech as this fair stone is in her deeds . . .

[5] In the opening of Così nel mio parlar, the poet wants to align his parlare with the lady’s harsh atti. In the opening of Inferno 32, the poet wants to align his dir with the harsh fatti of the pit of Hell. It is the same poetic program, transferred from conjuring a scene of violent and frustrated eros in the canzone to describing the violent “floor of the whole universe”: “fondo a tutto l’universo” (Inf. 32.8) in Inferno 32. Along with the same poetic program, Dante also transfers the same stylistic modality — harsh rhymes — from the canzone to the Inferno. The first verse of Così nel mio parlar vogli’esser aspro emphatically states the poet’s desire for harsh speech: a “parlar . . . aspro”.

[6] Using the same adjective aspro that he had used decades previously in the canzone Così nel mio parlar vogli’esser aspro, Dante at the end of Hell desires “rime aspre e chiocce”, harsh and rasping rhymes (he had previously used the adjective chioccia for Plutus’s “voce chioccia” in Inferno 7.2.): “S’io avessi le rime aspre e chiocce, / come si converrebbe al tristo buco” (Had I the crude and scrannel rhymes to suit the melancholy hole [Inf. 32.1-2]). The principle that the language used by the poet should be commensurate with the reality described also echoes Così nel mio parlar (the principle that language should be conveniens with respect to its topic is expressed in the verb “converrebbe” from convenire). In the canzone, Dante seeks commensurate poetic expression for a reality such that poetry cannot adequately render it: “no·l potrebbe adequar rima” (Così nel mio parlar, 21).

[7] Equipped with rime aspre, Dante will attempt language to adequar the reality he sees. In the canzone, the goal was to find language that matched the cold and stony harshness of the lady he loved. In Inferno 32, the goal is to find language that matches the cold and stony harshness of Hell. This is not the language of children, not the language of affect, not the language of warmth, love, and life:

ché non è impresa da pigliare a gabbo discriver fondo a tutto l’universo, né da lingua che chiami mamma o babbo. (Inf. 32.7-9)

for it is not a task to take in jest, to show the base of all the universe— nor for a tongue that cries out, "mama," "papa."

[8] The consonance between Così nel mio parlar and Inferno 32 goes further, involving an act of violence committed by the poet in both works. In Così nel mio parlar the poet imagines that he takes violent and erotic revenge on the lady for her resistance, in a scene that involves seizing her by her beautiful braids:

S’io avessi le belle trecce prese, che fatte son per me scudiscio e ferza, pigliandole anzi terza, con esse passerei vespero e squille: e non sarei pietoso né cortese, anzi farei com’orso quando scherza; e se Amor me ne sferza, io mi vendicherei di più di mille. (Così nel mio parlar, 66-73)

Once I’d taken in my hand the fair locks which have become my whip and lash, seizing them before terce I’d pass through vespers with them and the evening bell: and I’d not show pity or courtesy, O no, I’d be like a bear at play. And though Love whips me with them now, I would take my revenge more than a thousandfold. (trans. Foster & Boyde)

[9] In Inferno 32 Dante will pull hair again, and pull it violently. The hair is not that of a lady who rejects his desire, but the hair of Bocca degli Abati, the Florentine Guelph nobleman whom the poet brands as traitor of Florence in the battle of Montaperti (1260). Bocca now howls in pain (“latrando lui” [Inf. 32.105]; “se tu non latri” [108]), as Dante once howled in desire for the stony lady: “Ohmè, perché non latra / per me, com’io per lei, nel caldo borro?” (Alas, why does she not howl / for me in the hot gorge, as I for her? [Così nel mio parlar, 59-60]).

[10] In this way Dante consciously and deliberately channels the erotic frustration of his early canzone into his political anger toward Bocca degli Abati: from a violent eros that remains in the private and subjective domain of lyric poetry, he moves to the violent collective history of Florence and Tuscany. He shows us how direct is the line from the private to the public, and how violence is the constant in both domains. He also shows us his own ability to move beyond the gendered stereotypes that inform the hair-pulling of the early canzone and that are part of the vision tradition in which the Commedia participates. As I wrote in “Dante’s Sympathy for the Other”:

In the earliest Christian vision, St. Peter’s Apocalypse (2nd c. CE), we find women hung by their hair, hair that they plaited «not for the sake of beauty but to turn men to fornication», and men «hung by their loins in that place of fire» (Gardiner 1989, 6). The sexuality and shame-value of hair has a long history: there were specific laws in Europe on hair pulling, modulating in severity depending on whether the hair pulled was male or female, and whether the culprit were free, or slave. Women’s hair remains sexualized in Italian love poetry of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and Dante himself in one of his most erotic lyrics imagines grabbing his resistant lover by her beautiful golden braids (Così nel mio parlar, 63-67). But in the otherworld of the Commedia, Dante imagines no women hung or pulled by their hair. The aggressively sexualized hair-pulling of the canzone feeds not into the Commedia’s treatment of female sexual sin but into the shaming of a man in Inferno 32 (a canto whose opening request for «rime aspre e chiocce» echoes the incipit of Così nel mio parlar). Rather than an adulterous woman, the hair-pulling of Inferno 32 involves Bocca degli Abati, the Florentine arch-traitor of the battle of Montaperti: a man. (“Dante’s Sympathy for the Other”, pp. 178-79)

[11] The lexicon of Così nel mio parlar will continue to resonate in the lexicon of the Ugolino episode of Inferno 32-Inferno 33. Here is a sample: “impetra” (Così nel mio parlar, 3) ⇒ “sì dentro impetrai” (Inf. 33.49); “cruda” (Così nel mio parlar, 4) ⇒ “come la morte mia fu cruda” (Inf. 33.20); “rodermi” (Così nel mio parlar, 25) ⇒ “che frutti infamia al traditor ch’i’ rodo” (Inf. 33.8); “co li denti d’Amor già mi manduca” (Così nel mio parlar, 32) ⇒ “e come ’l pan per fame si manduca” (Inf. 32.127). Again, we see how purposefully Dante uses his erotic canzone to stage a transition from sexualized and lyric violence in the private domain to political and social violence in Inferno.

* * *

[12] The sin that Dante stipulates for the ninth circle of Hell is treachery: fraud practiced on those who trust us, as he defines it in Inferno 11.53. The ninth circle is thus a continuation of the eighth, which features sinners who deceived people with whom they shared no special bonds of trust. Dante has given about half the real estate of Hell to fraud, for we enter the circle of fraud in Inferno 18 and fraud persists as an organizing principle until the end of Inferno.

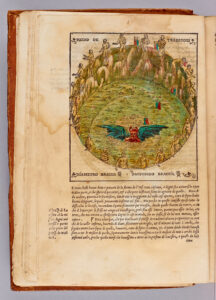

[13] When the travelers arrive at the fondo dell’universo, the very bottom of the universe, also known as the ninth circle, they see ice: ice so thick that if certain very large and particularly stony mountains fell upon this ice, it would not crack (verses 25-30). One of the mountains named in this passage is “Pietrapana” (from Pietra Apuana), a mountain in the Apuan Alps in Tuscany that is now called Pania della Croce. Its very name, Pietrapana, reminds us of the icy, cold, stony, lady-pietra of the rime petrose.

[14] And indeed, as the poetic program of lowest Hell is imprinted with a rima petrosa, so too is the air, the landscape, the very “weather” of this place. The petrose are winter poems, poems that explore a love that renders the self stone-dead and ice-cold. The icy death of the rime petrose is subjective and psychological, part of the lyric trope whereby the self is “wintry” and dead while the rest of creation participates in the warm springtime of reciprocated love. Dante has now projected that trope onto objective reality: it has been conjured as the frozen lake of Cocytus, the frozen core — the frozen heart — at the center of the universe.

[15] Ice was no more a popular descriptor for Hell in the medieval cultural imaginary than it is in ours. Dante ignores convention to make his point: ice signifies lack of all warmth, lack of all life, lack of all love. The ninth circle features the icy coldness of death. The ice of Cocytus is maintained by a frigid wind of hate and un-love, which (as we will learn in Inferno 34) is generated by Lucifer’s bat-like wings. A first mention of the frigid wind of lowest Hell is found in verse 75 of this canto: “e io tremava ne l’etterno rezzo” (and I was trembling in the eternal breeze [Inf. 32.75]).

[16] The smooth ice of Cocytus, which the extreme cold has caused to take on the appearance of glass (“avea di vetro e non d’acqua sembiante” [it looks like glass, not water Inf. 32.24]), serves as a mirror of the self. Camicion de’ Pazzi says to Dante, in verse 54, “Perché cotanto in noi ti specchi?”: “Why do you so mirror yourself in us?” (Inf. 32.54). Cocytus is a lake of glass in which the self is mirrored, for the journey through Hell, which now draws to an end, is about recognizing evil not only in others: we must also recognize evil in ourselves.

[17] The ice is the home of traitors, and betrayal is human behavior that is premised on lack of love. Here in the ninth circle we find four types of betrayal (although as we shall see one type easily bleeds into another): betrayal of family, betrayal of country or party, betrayal of friends and guests, betrayal of benefactors. Dante imagines that the ice of Cocytus is roughly divided into four zones accordingly and that the sinners exhibit different postures in the ice according to which zone they inhabit. These sinners of lowest Hell are those who defiled the bonds of family and community that we humans hold most dear.

[18] The first section of Cocytus, devoted to the betrayal of family, is called “Caina” (58) after biblical Cain who killed his brother, Abel. Dante first uses this label in the ferocious description of two brothers, Napoleone and Alessandro degli Alberti. These brothers are locked together in the ice for eternity:

D’un corpo usciro; e tutta la Caina potrai cercare, e non troverai ombra degna più d’esser fitta in gelatina. (Inf. 32.58-60)

They came out of one body; and you can search all Caina, you will never find a shade more fit to sit within this ice.

[19] The mutual hatred (based on quarrels over inheritance) of these two brothers, Napoleone and Alessandro, counts of Mangona, led to their killing each other. The double fratricide was followed in the next generation by the killing of Napoleone’s son, Orso, by the hand of Alessandro’s son, Alberto (see Sapegno’s commentary, ad locum, who cites Barbi).

[20] The killing of brother by brother reminds us of the first usage of the word “Caina”: it appears in Inferno 5, where it is used by Francesca da Rimini. She refers to the future infernal resting-place of her husband, Gianciotto Malatesta, guilty of killing both herself, his wife, and his brother Paolo, her lover, and thus destined to join the traitors of family: “Caina attende chi a vita ci spense” (Caina waits for him who took our life [Inf. 5.107]). Interestingly, another parallel between the counts of Mangona and the Malatesta clan is the transmittal of the desire for vengeance to the next generation. For, as I note in an essay on Francesca da Rimini (cited in Coordinated Reading), Gianciotto’s son Ramberto killed Paolo’s son Uberto, just as Alessandro’s son Alberto killed Napoleone’s son Orso:

The struggle for power among the cousins was so fierce, and betrayal so customary, that Gianciotto’s son Ramberto would eventually invite Paolo’s son Uberto to dinner and there, in concert with other family members, have him killed. (“Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender”, p. 24)

[21] As the Malatesta family demonstrates all too well, there is no clear demarcation between family betrayal and political betrayal. This blurring of the lines between family ties and the exercise of political power, systemic in Dante’s society, comes into focus in the episode that dominates the next canto, that of Count Ugolino della Gherardesca.

[22] There is another tidbit of Malatesta history that relates Francesca’s story to Inferno 32. Toward the end of this canto, Dante presents the political traitor Tebaldello de’ Zambrasi of Faenza: “Tebaldello, / ch’aprì Faenza quando si dormia” (he who unlocked Faenza while it slept [Inf. 32.122-23]). Tebaldello’s daughter Zambrasina de’ Zambrasi married the widower Gianciotto Malatesta and bore him five children after Francesca’s demise, “thus achieving the unique status of being wife of one traitor in Dante’s hell and daughter of another” (“Dante and Francesca da Rimini”, p. 19).

[23] Here I would like to offer a point about the compositional process of Inferno, based on the presence of “Caina” in Inferno 5. Whatever the form of outlining or note-keeping that Dante undertook in composing his intricate otherworld, he evidently had worked out at least a basic formal structure, as indicated by the name Caina appearing as early as Inferno 5. We can infer that Dante had planned the structure of Hell in some detail, and that he likely understood that he was creating a text that would require commentary. The same early commentators who explain the identity of Francesca da Rimini (an actual person) also have the task of explaining what the word “Caina” (a fictional signifier) means in Inferno 5.107.

[24] However, while information about the identity of Francesca da Rimini has to be imported by the commentator from outside of the text, the significance of the word “Caina” in Inferno 5.107 is entirely internal: it can only be ascertained by reading Inferno 32. As this example shows, by treating his own virtual reality as equally deserving of gloss as a simile drawn from Ovid or the identity of a historical character, Dante contributes to the compelling verisimilitude of his text.

* * *

[25] The second zone of the ninth circle, ”Antenora” (88), contains political traitors, including Bocca degli Abati, the Florentine Guelph magnate whom Dante believed betrayed his fellow Guelphs at the battle of Montaperti (historians have not succeeded in confirming the identity of the traitor of Montaperti). In Dante’s account, Bocca degli Abati’s betrayal of Florence during the battle of Montaperti — he cut off the hand of the Florentine standard-bearer — turned the tide and led to the victory of the Sienese and the Florentine Ghibellines over the Florentine Guelphs.

[26] Looking back at the chronicles of Florentine history in the Inferno that feature Montaperti — in particular Inferno 10 and Inferno 28 — we see that the battle of Montaperti is, for Dante, like a festering wound that never heals. The exiled Florentine Ghibelline, Farinata degli Uberti of Inferno 10, led the Sienese forces to victory over their arch-rival Florence. The victory at Montaperti initiated a violent back-and-forth as Ghibellines and Guelphs exchanged power and exiled each other throughout the subsequent decades. The violence of the encounter with Bocca degli Abati reflects this terrible history: Dante suspects he is speaking to Bocca and, when Bocca refuses to reveal his name (a name that is then “betrayed” to Dante by another traitor in Inferno 32.106), the pilgrim threatens to pull out his hair (Inf. 32.97-99).

[27] The sinner who betrays Bocca is subsequently revealed by Bocca to be Buoso da Duera, who betrayed Manfredi and the Ghibelline cause: Buoso da Duera accepted a bribe from Charles of Anjou and withdrew all opposition to the passage of the French through Lombardy, thus leading to the defeat of Manfredi (Frederick II’s illegitimate son) at Benevento in 1266. The defeat of the imperial cause at the battle of Benevento is another tragic waystation in a history that Dante deplores. In this episode Dante offers both a Ghibelline traitor (Buoso da Duera) and a Guelph traitor (Bocca degli Abati), but his personal passionate hatred is reserved for the Guelph.

[28] Dante tells Bocca that he will heap shame on him by bringing “true news” of his whereabouts back to earth: “ch’a la tua onta / io porterò di te vere novelle” (for I shall carry / true news of you, and that will bring you shame [Inf. 32.110-11]). Here Dante threatens Bocca with the stigma of profound shame and dishonor — the very “onta” of the Geri del Bello episode discussed in the Commento on Inferno 29. This is the onta that in the Geri del Bello episode Dante refused to assume for himself. For Dante, the failure to perform vendetta does not merit onta, while the betrayal of one’s fellow citizens to their deaths absolutely does.

[29] The passion that Dante brings to the Bocca degli Abati episode simmers in its fierce repartee. Buoso asks Bocca why he is howling in pain, and wonders aloud — as the pilgrim pulls his hair — “what devil is touching you?”:

quando un altro gridò: Che hai tu, Bocca? non ti basta sonar con le mascelle, se tu non latri? qual diavol ti tocca?” (Inf. 32.106-8)

when someone else cried out: “What is it, Bocca? Isn’t the music of your jaws enough for you without your bark? What devil’s at you?”

[30] Of course, the “devil” that is touching Bocca is none other than Dante, who has temporarily become a minister of God’s justice in fulfillment of the infernal mandate “Qui vive la pietà quand’è ben morta” (Here pity lives when it is truly dead [Inf. 20.28]). We also note that Dante is participating in the kind of quarrel that Virgilio had just recently, at the end of Inferno 30, rebuked him for even watching. As I suggest in the Commento on Inferno 30, we should infer that Virgilio’s rebuke was a sign of the Roman poet’s limited understanding of the work of Christian Hell, rather than a sign of the pilgrim’s shameful behavior.

[31] In the last section of Inferno 32, the travelers see one sinner savagely eating the skull of another, digging his teeth, with terrible precision, “right at the place where brain is joined to nape”: “là ’ve ’l cervel s’aggiugne con la nuca” (Inf. 32.129). The pilgrim addresses the soul as “one who shows his hatred for the one he eats” through such a “bestial sign”: “O tu che mostri per sì bestial segno / odio sovra colui che tu ti mangi” (O you who show, with such a bestial sign, / your hatred for the one on whom you feed [Inf. 32.133-34]). This is the beginning of the encounter with Count Ugolino della Gherardesca, a Pisan nobleman, whose story dominates Inferno 33.

[32] The distortion of language that was signaled by Nembrot’s gibberish in Inferno 31 has now found its fitting rubric. Down here language is a “bestial segno” (bestial sign [Inf. 32.133]). These souls would have been better off had they been “pecore e zebe” (sheep and goats [Inf. 32.15]): now they chatter their teeth like storks (“mettendo i denti in nota di cicogna” [Inf. 32.36]) and howl like dogs (“latrando lui con gli occhi in giù raccolti” [Inf. 32.105]). Their language is not poorly uttered or composed; as we will see, Ugolino is an accomplished rhetorician. Rather, it does not respect the human ties of family and community that are the reason for language’s existence: it is not used to comfort and console.

[33] The language of Cocytus is used — like Buoso’s and Bocca’s language in Inferno 32 — to betray. We have reached the heart of ice at earth’s core.

Return to top

Return to top