- What does not happen in Dante’s circle of lust: the Commedia does not include the genital tortures that are featured in vision literature and contemporary artwork (see for instance Giotto’s Last Judgment in the Scrovegni Chapel)

- The contrast reveals that Dante de-sexualizes lust

- That said, Dante makes his second circle significantly more “hellish” than his first, putting the infernal judge Minos, adjudicator of the damned, at the threshold of the second circle

- Dante’s treatment of lust focuses not on illicit sexual actions per se but on the subordination of reason to desire

- The contrapasso of the second circle is the infernal windstorm (“bufera infernal” [Inf. 5.31]), whose metaphoric connection to lust works by analogy: the wind buffets and controls the lustful in the afterlife in the same way that their passions buffetted and controlled them while in this life

- A new source text for Dante’s contrapasso: Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 3.1, where the philosopher treats voluntary and involuntary action and uses the example of a man being carried off by the wind

- The encounter with Francesca da Rimini features the literature of courtly love; in this context, Dante is able to meditate on the courtly tradition, including the Italian lyric tradition, from the Sicilians to Guinizzelli and Cavalcanti

- Echoing literary authorities, Francesca deploys the courtly doctrine that love is a compulsive force, that it cannot be resisted, and that it effectively deprives us of our free will

- The autobiographical component: Dante himself had written poetry in which he denied that free will can exist within the domain of love, most explicitly in the sonnet Io sono stato con Amore insieme

- Working from ideas already present in his moral canzone Doglia mi reca, in Inferno 5 Dante insists that reason and love can and must coexist: a passion that is antithetical to reason, that is not the product of a free will, cannot be called love

- The word amore and how to construe it:

- in Inferno 2, “amore”, rightly construed, is aligned with reason, and leads to salvation: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (Inf. 2.72)

- in Inferno 5, “amore”, wrongly construed, is not aligned with reason, and leads to death: “Amor condusse noi ad una morte” (Inf. 5.106).

- A different vision of Francesca: we can historicize her and uncover her gendered history as dynastic wife and political pawn who attempts to exert agency in a patriarchal world. From this historicized perspective, it is less important that Dante puts Francesca into his Hell than that he saves her to history, preserving her from oblivion and becoming Francesca’s historian of record. For the first historicized reading of Dante’s Francesca, see my essay “Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender”, listed in Coordinated Reading.

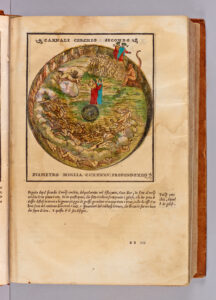

[1] We begin by putting Dante’s treatment of lust as a sin into historical context. We can do this by comparing Dante’s treatment of lust in Inferno 5 to that of various moralistic traditions, both written and visual: to vision literature, to didactic poetry and sermons, and to contemporary artwork.[1]

[2] The distance between Dante and the various moralistic traditions is immense. The instructive contrast helps us to realize that Dante is not particularly interested in criminalizing sex per se: he does not raise the usual hue and cry about what the moralists call fornication.

[3] The visionaries follow a tradition in which punishment is inflicted on the sinful body part and are insistent that the tortures inflicted on fornicators are genital tortures. Visions create a context that helps us to see that Dante, by contrast, de-sexualizes lust.

[4] In the earliest Christian vision, St. Peter’s Apocalypse (2nd c. CE), we find women hung by their hair, hair that they plaited “not for the sake of beauty but to turn men to fornication”, and men “hung by their loins in that place of fire” (Gardiner, ed. and trans., Visions of Heaven and Hell before Dante, p. 6). At the end of the vision tradition is Thurkill’s Vision (dated 1206, of English provenance), whose adulterers must fornicate publicly in an infernal amphitheater, and then tear each other to pieces:

An adulterer was now brought into the sight of the furious demons together with an adulteress, united together in foul contact. In the presence of all they repeated their disgraceful love-making and immodest gestures to their own confusion and amid the cursing of the demons. Then, as if smitten with frenzy, they began to tear one another, changing the outward love that they seemed to entertain toward one another before into cruelty and hatred. (Gardiner, ed. and trans., Visions of Heaven and Hell before Dante, pp. 230-231)

[5] Visual depictions of Hell are similarly focused. The treatment of the lustful in the Last Judgment of Dante’s contemporary Giotto (1267-1337 c.), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padova, offers graphic images of what art historians Anna Derbes and Mark Sandona call “torments directed at genitalia”. They describe Giotto’s figures thus:

For instance, just below Satan’s left arm, on the bristly back of a serpentine monster, is a soul doomed to spend eternity with a reptilian green demon gnawing on his penis. Above and to the right of Satan, a black demon grips another man’s penis in pincers. Hanging to the right are four more damned souls, two of whom — one male, one female — are suspended by their genitals, another by his tongue, and the fourth by her long hair, a common sign of luxuria. The fact that her hair is braided may also signify her concupiscence. (Derbes and Sandona, The Usurer’s Heart: Giotto, Enrico Scrovegni, and the Arena Chapel in Padua, p. 66)

[6] In a 1998 article published in The Art Bulletin that preceded the book cited above, Derbes and Sandona characterize the genital tortures thus: “These particular forms of torture — surely visual versions of Dantean contrappasso — are especially apt here” (p. 284). If there is one thing that the genital tortures of the Scrovegni Chapel are not, they are not “visual versions of Dantean contrappasso”. I cite the 1998 remark, duly corrected in the later book, because it is so instructive regarding the inaccuracy with which popular perception of the Commedia (even among scholars) has sedimented. It is thus reflexively assumed that the Inferno is the poetic version of a vision like Thurkill’s Vision, or the poetic version of Giotto’s Last Judgment.

[7] Importantly, Dante does not imagine sexualized torture at all, either here in his treatment of (heterosexual) lust or later in his treatment of what he calls sodomy. There is, in fact, a complete absence of sexualized torture in the Commedia.[2]

* * *

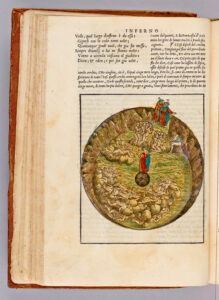

[8] Dante offers a crisp definition of lust. It is a philosophical definition in that he defines the “carnal sinners” as those “who subjugate reason to desire”: “i peccator carnali, / che la ragion sommettono al talento” (Inf. 5.38-9). Lust is the misalignment of our faculties, with the result that our passions control us, rather than reason. After this ethical definition is put forward, Dante-poet stages an encounter with a charismatic sinner, Francesca da Rimini, who uses thrillingly seductive language — language that draws on both courtly love lyrics and Arthurian romance — to subvert the information contained by the prior ethical definition.

[9] Here Dante follows a narrative method that he uses consistently, of first giving us information and then challenging our ability to integrate that information into our understanding of the possible world depicted by the poem. For instance, although “we are duly informed that ‘Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore’ (Justice moved my high maker [Inf. 3.4]), this is information that we will internalize — if at all — only after completing much of the voyage through hell, not here at the outset” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 31).

[10] Similarly, in Inferno 5 Dante not only defines lust very clearly, but he further signposts the gravity of the sin by placing Minos, the adjudicator of the damned, at the entrance of the second circle, where he wraps his phallic tail around the sinners to denote the circle to which the sinner will be sent. Ludovico Castelvetro thought Dante should have placed Minos before the first circle, in order that no sinner escape the purview of justice. Not only does the placement of Minos increase the privileging of Limbo, but it casts a proleptic shadow on Francesca’s arrival in the second circle: “Francesca’s efforts are so successfully directed at dulling the reader’s perception of her sinfulness that it is bracing to recall that she, too, passed by Minos and was judged by him” (“Minos’s Tail”, p. 150, listed in Coordinated Reading).[3]

[11] We turn now to the contrapasso that Dante devises for Inferno 5. Dante’s treatment of lust emphasizes the psychology of desire: his adulterers are tossed about by a hellish wind — the “bufera infernal” of verse 31 — as in life they were tossed about by their passions. The fourteenth-century commentator Guido da Pisa offers the gloss: ‘‘the lustful are moved in this world by every wind of temptation, so that their souls are always in continual motion and continual tempest’’. He cites Isaiah: ‘‘Cor impii quasi mare fervens quod quiescere non potest’’ (The heart of the wicked man is like a troubled sea that cannot rest). Dante’s contrapasso also draws on the Augustinian analysis of desire, based on a dialectic between human motion and divine repose, between the human cor inquietum — unquiet heart — with its restless and unfulfilled longings (“inquietum est cor nostrum” [Confessions, ch. 1]) and the eternally fulfilled quies of God.

[12] In a 1998 essay on Inferno 5, I added a passage from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 3.1 to the interpretive matrix on the canto, suggesting a new source for the contrapasso. The importance of this Aristotelian passage for Inferno 5 has, to the best of my knowledge, gone unnoticed by the previous commentary tradition. (See “Dante and Cavalcanti, on Making Distinctions in Matters of Love: Inferno 5 in Its Lyric and Autobiographical Context”, listed in Coordinated Reading),

[13] The passage in question comes from the beginning of Aristotle’s discussion of voluntary and involuntary action in Nicomachean Ethics 3.1, where the philosopher provides two examples of involuntary action. One of the two examples is that of a person being carried off by a wind:

Those things, then, are thought involuntary, which take place by force or owing to ignorance; and that is compulsory of which the moving principle is outside, being a principle in which nothing is contributed by the person who acts — or, rather, is acted upon, e.g., if he were to be carried somewhere by a wind, or by men who had him in their power. (Nicomachean Ethics 3.1.1109b35–1110a4; trans. David Ross, 1925; rev. ed. [Oxford: Oxford UP, 1980], p. 48)

[14] Many years later, I developed further the analysis of Nicomachean Ethics 3.1 and Inferno 5, starting from the question of what Dante achieves for his treatment of lust by appropriating Aristotle’s wind, one of the philosopher’s two examples of a force that can compel involuntary action.[4] I argue that Dante uses Aristotle in order to emphasize the importance of free will. Specifically, he employs Aristotle’s example of compulsive force in order to illuminate the moral weakness of the doctrine of courtly love, with its insistence that love is an external force that can compel us to act against our will, as though love were in fact an irresistible force like the wind of Nicomachean Ethics 3.1.

* * *

[15] Love as an overwhelming force that cannot be withstood is a staple of the vernacular love lyric tradition. Giacomo da Lentini, the leader of the first Italian school of poetry, the Sicilian school, offers the language of passive surrender to love that Francesca will later use: for example, in the canzone Madonna, dir vo voglio, Giacomo writes “como l’amor m’ha priso’’ (as love has taken me [Madonna, dir vo voglio, 2]) and ‘‘di tal guisa Amor m’ha vinto’’ (in such fashion love has conquered me [Madonna, dir vo voglio, 72]). Another Sicilian poet, Guido delle Colonne, also presents love as a force that dominates him, writing in the canzone Ancor che l’aigua of love having taken and seized him (“sì m’ave preso e tolto” [33]). In the canzone Amor, che lungiamente m’hai menato Guido delle Colonne conjures Vergil’s “Omnia vincit Amor” (Love conquers all) when he writes “Amor che vince tutto” (Love that conquers all [24]).

[16] Guido delle Colonne’s canzone Amor, che lungiamente m’hai menato begins with a metaphor in which the lover is a horse and Love is the rider of that horse. Thus, the lover is dominated and subdued by Love. This canzone, which deploys the same verb menare that is so frequent in Inferno 5, is, as I have written, ‘in effect a lyric version of Inferno 5 without the eschatological context”:

The Augustinian dialectic between menare and posare (terms that will govern Inferno 5 as well) shapes the canzone from the outset, where the compulsive force of love is compared not to the roiling force of a gale on the sea but to the severe control of a rider on his mount; the lover begs love to loosen the reins by which he is so tightly bound: “Amor, che lungiamente m’hai menato / a freno stretto senza riposanza, / alarga le toi retene in pietanza” (1-3). (“Dante and Cavalcanti”, p. 75)

[17] Dante began his poetic life as a lyric poet working within the conventions of courtly love and in the context of an eros that is viewed as an imperious force that cannot be withstood. In his very early sonnet to Dante da Maiano, Savere e cortesia, Dante Alighieri declares that there is no power that can impede love: “ché nulla cosa gli è incontro possente (for nothing has the power to take him [Love] on” [Savere e cortesia, 13]). (Further discussion of Savere e cortesia within the context of Dante’s long meditation on compulsion and the will may be found in Dante’s Lyric Poetry, cited in Coordinated Reading.)

[18] Dante most forcefully expresses the idea that Love has the power to compel us in the sonnet Io sono stato con Amore insieme, where the poet uses philosophical language and explicitly raises the concept of free will. Dateable to between 1303 and 1306 (thus about a decade after the theologizing of love that takes place in the Vita Nuova), Io sono stato characterizes love as an ineluctable force that overpowers reason and free will: “Però nel cerchio della sua palestra / libero albitrio già mai non fu franco” (So in the sphere of its authority / free will has never been completely free [9–10]). Still more surprising, the poet claims to have experienced this passion for the first time in his ninth year, that is, toward Beatrice:

Io sono stato con Amore insieme dalla circulazion del sol mia nona, e so com’egli afrena e come sprona e come sotto lui si ride e geme. Chi ragione o virtù contra gli sprieme fa come que’ che [’n] la tempesta suona ... (Io sono stato, 1–6)

I’ve dwelled together with the god of Love from when the sun had circled back nine times, and I know how he checks and how he prods and how one laughs and cries beneath his rule. Opposing him with force or reason is like sounding the alarm within a storm ... (Richard Lansing trans.)

[19] Dante’s lyric poetry is a laboratory in which we can see him take on and consider differing and antithetical views of love: in some poems he supports the idea that Love is a compulsive force and in others he challenges that idea, insisting on the role of reason. The idea of love as a compulsive force is the ideological foundation of the rime petrose (circa 1296), as it is of the later Io sono stato and of Amor, da che convien pur ch’io mi doglia, the so-called canzone montanina (circa 1306), which features a Cavalcantian view of love as an ineluctable and lethal force. As I have discussed in numerous venues, including the Introduction to my commentary Dante’s Lyric Poetry, Dante works through these various positions in non-linear fashion, not developing along a straight and overdetermined trajectory. For instance, he takes aim at the idea of love as compulsion in Doglia mi reca, a moral canzone written post-exile but before the canzone montanina.

[20] Years prior to the adoption of Aristotle’s example of the wind as a compulsory force for the contrapasso of Inferno 5, Dante had already brought an Aristotelian ethical dimension to his lyric poetry. The canzone Le dolci rime includes a translation of Aristotle’s definition of virtue from the Ethics (see the Commento on Inferno 1, par. 26). Dante’s interest in the regulation of desire by reason leads to a foregrounding of the value of misura, the moderating force that keeps a person hewing to the Aristotelian mean. Over time, and following a non-linear path, Dante becomes passionately invested in the belief that desire can be withstood, that reason can and must triumph.

[21] Moreover, by insisting that reason can triumph over desire, and that the issue is for us to keep our faculties in proper alignment, Dante adopts an Aristotelian template that enables him to withstand the siren call of dualism. For, counter to the tradition of Dante studies that for centuries has insisted on the binary of secular versus divine love, Dante’s template for conceptualizing desire is not dualistic.

[22] Dante does not believe that desire per se is bad. He could not believe that desire is bad and hold, as he writes in Purgatorio 18, that “desire is spiritual motion”: “disire, / ch’è moto spiritale” (Purg. 18.31-32). Desire is the motor that moves us along the path of life, and ultimately, if we make the right choices, to God. We are propelled by desire, whether toward good or toward evil. Thus, Dante is not saying that desire is bad, but that it must be controlled, and that it must be subordinate to reason. This idea, that desire must be kept in check by reason, that reason must be the rider of the horse and not vice versa, is, as we know, crisply stated in Dante’s definition of lust. It is also a nod to the fundamental Aristotelianism that governs all the circles of incontinence in Dante’s Hell.

* * *

[23] In Inferno 1, the word “amore” enters the Commedia for the first time as the divine love that moves the stars. Love is the life force, the force that binds and moves the universe; it is coexistent with intellect and with truth. Therefore, for Dante, that which we can properly call love can never be antithetical to intellect, reason, and truth.

[24] In the moral canzone Doglia mi reca nello core ardire, written post-exile in the first decade of the fourteenth century, Dante had already explained that some call by the name of ‘‘love’’ that which is really mere bestial appetite: “chiamando amore appetito di fera” (calling bestial appetite [by the name] love [Doglia mi reca, 143]). Such people disjoin love and reason, because they believe that love resides ‘‘outside of the garden of reason’’: “e crede amor fuor d’orto di ragione” (147).

[25] Dante’s point in Doglia mi reca, to which he gives dramatic shape through Francesca’s use of the word “amore” in Inferno 5, is that we often misuse the word “love”. Love, properly understood, cannot exist “outside of reason’s garden”. For Dante a passion that is antithetical to reason cannot be love.

[26] The souls whom we meet in this canto have all subordinated reason to desire, thus inverting the proper functioning of our human faculties. For Dante, these “carnal sinners” did not experience what he would call “love”. They experienced lust, lussuria. And yet the carnal sinner who speaks to Dante at length, Francesca da Rimini, repeatedly and thrillingly characterizes her experience as “love”.

[27] By granting Francesca the lexicon of love, a vocabulary dominated by the noun amore and the verb amare, Dante scripts a performance and challenges his readers to interpret it. This is dramatic art, in which individual sinners use words that suit them, and not necessarily in a way that agrees with the narrator’s definitions.

[28] Francesca’s performance is heightened by its literary register and by its intertextual resonances. A romantic aura envelops Dante’s encounter as Francesca tells the story of how she fell in love. Her story draws on the language and the style of two quintessentially amorous literary genres: the love lyric, and the Arthurian prose romance. The first part of her account is stylized and abstract and draws on the lyric, while the latter part is more life-like and detailed and draws on the prose romance, in particular on the French Lancelot romance. Most importantly, drawing on these important genres, Dante scripts for his charismatic sinner Francesca a seductive rhetorical power that makes his reader “forget” the definition of lust that he as narrator had so recently provided.

[29] Francesca uses the tenets of the courtly love lyric to ascribe all agency to Love, conjured by her as an imperious and coercive force that she and Paolo could not possibly have resisted or withstood. In her three famous terzine beginning with “Amor” (and in which “Amor” is always the grammatical subject of the verb), she explains that 1) Love compelled Paolo to fall in love with Francesca (100-2), 2) that Love compelled Francesca to reciprocate the love of Paolo (103-5), and 3) that Love led both of them to their deaths (106-8).

[30] In the same way that Francesca exploits the love lyric tradition as outlined above, to show that she and Paolo were compelled to do as they did, she later explains that a book, the Lancelot romance, caused Paolo first to kiss her. Indeed, in her account, the book served as the facilitator of their adulterous romantic encounter, which occurred while they were reading it. In the verse “Galeotto fu ’l libro e chi lo scrisse” (a Gallehault indeed, that book and he who wrote it [Inf. 5.137]), Francesca literally blames the book that she and Paolo were reading for their liaison: the book made us do it! The book is said, through complex literary resonance, to have behaved like Gallehault, the character in the Lancelot romance who facilitated the first kiss between Lancelot and Guinevere. The book “and he who wrote it” — the book’s author — are thus responsible for her first adulterous kiss.

[31] In all this, we see how Dante continues to draw our attention to the profoundly mistaken idea that love comports lack of free will, an idea promoted by the literature of the courtly tradition in both its lyric and romance forms.

* * *

[32] Dante-author, who as a young poet had written the very kind of love poetry that Francesca is here quoting, creates a dramatic scene at the end of the canto in which Dante-protagonist is unable to keep a critical distance from Francesca and her story. Dante-protagonist “falls for her”, literally, falling down in a dead faint in the canto’s last verse: “E caddi come corpo morto cade” (And then I fell as a dead body falls [Inf. 5.142]). The pilgrim swoons on the floor of Hell, in a vivid enactment of the Cavalcantian “love” that leads to death: “Amor condusse noi ad una morte” (Love led us to one death [Inf. 5.106]).

[33] The idea of a love that leads to death is pervasive in medieval lyric and romance, but its most philosophically sophisticated exponent is Dante’s “first friend” and contemporary, Guido Cavalcanti. Dante is here evoking the Cavalcantian love that held sway over him in an earlier phase of his lyric development (see, for instance, my discussion of the canzone Lo doloroso amor in Dante’s Lyric Poetry). As discussed above, a complex developmental trajectory is invoked in Inferno 5, one that goes all the way back to the tenzoni with Dante da Maiano and that passes through the Sicilian, Guinizzellian, and Cavalcantian phases of his poetics. These phases were mapped in the Vita Nuova long before being mapped in Inferno 5 (see Dante’s Poets and Dante’s Lyric Poetry).

[34] While in the Vita Nuova the turn to Guinizzelli frees the young Dante from Cavalcanti, Inferno 5 offers an autobiographically truer assessment: of his contemporaries, Cavalcanti exerts the greatest hold on Dante’s imagination.

[35] In this developmental trajectory, Dante arrived at his mature moral formulation of the interaction between passion and reason in the moral canzone Dogia mi reca, where love must belong “to reason’s garden” in order to be called “love”. As we have seen, the final stanza of Doglia mi reca adumbrates one of the fundamental issues of Inferno 5, namely whether the use of the name “love” is sufficient guarantee that we are in fact talking of love. Dante is concerned with human desire, but also with how we use language when we deal with desire. Francesca talks repeatedly of “love”, but the narrator instructs us otherwise, telling us that we will encounter in this circle not lovers but “carnal sinners, / who subjugate reason to desire” (Inf. 5.38-39).

[36] Similarly, Doglia mi reca raises the possibility that someone who desires — a woman who desires, no less — can define love in a self-serving way, can justify her actions by calling her appetite by the name of love. As with Francesca, although the lady of the canzone may use the word amore, she misapplies the signifier, for the impulse that grips her is a “bestial appetite” that she dignifies with the name “love”: “chiamando amore appetito di fera” (calling love [what is] bestial appetite [Doglia mi reca, 143]). In the canzone, this lady is doomed to perish, to perdition: “Oh cotal donna pera” (O let such a woman perish [Doglia mi reca, 144]).

[37] In Inferno 5, as in the great medieval romances and in much lyric poetry, particularly that of Dante’s best friend Guido Cavalcanti, love is that which leads to death. For Cavalcanti, love leads to death precisely because it is disjoined from reason and intellect, a disjunction that Cavalcanti theorizes in his highly technical philosophical canzone Donna me prega. The love of which Cavalcanti wrote in Danna me prega is literally death-inducing: ‘‘Di sua potenza segue spesso morte’’ (From love’s power death often follows [35]). Guido’s love leads to death. For Dante, what Guido calls love cannot truly be love.

[38] Dante broke with Cavalcanti and other vernacular precursors when he theologized the beloved in the early canzone Donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore (VN 19). He broke with Cavalcanti even more thoroughly when he theorized a love that belongs “in reason’s garden” in the canzone Doglia mi reca. The positing of a love that is aligned with reason in Doglia mi reca, grafted onto the theologized courtliness of Donne ch’avete and onto the idea of consolation in the canzone of mourning Li occhi dolenti (VN 31), leads to the salvific love that moved Beatrice to come to Dante’s aid in Inferno 2: “amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare” (love moved me, and makes me speak [Inf. 2.72]).

[39] For the mature Dante, what Francesca and Cavalcanti call love is not love at all. As the canzone Doglia mi reca affirms, love grows in reason’s garden. In the absence of reason and absent the excercise of free will, there can be no love.

[1] I first systematically used vision literature as a benchmark for thinking about Inferno 5 in my 1998 essay “Dante and Cavalcanti (On Making Distinctions in Matters of Love): Inferno 5 in Its Lyric and Autobiographical Context”, and I similarly used the Last Judgments of Giotto and Taddeo di Bartolo in my 2011 essay “Dante’s Sympathy for the Other, or the Non-Stereotyping Imagination: Sexual and Racialized Others in the Commedia”; see Coordinated Reading.

[2] The possible exception would be the treatment of the thieves, to be discussed in Inferno 24 and 25 of this Commento.

[3] Castelvetro’s comments, cited in “Minos’s Tail”, may be found in Sposizione di Lodovico Castelvetro a xxix Canti dell’‘Inferno’ dantesco (Modena: Società tipografica, 1886), 73.

[4] See “Dante and Aristotle on Voluntary and Involuntary Action: Nicomachean Ethics 3.1 in Inferno 5 and Paradiso 3–5”, listed in Coordinated Reading.

Return to top

Return to top