Purgatorio 32 forces us to turn our attention, in a kind of “conversion” of the gaze: Dante the individual must convert his gaze away from the beauty of his lady and back to the universal and the macrocosmic. The narrator thematizes this turning of attention in his story-line, for the pilgrim is ordered to look away from Beatrice by the theological virtues, who tell him that he is staring too fixedly, “Troppo fiso!” (Purg. 32.9):

Tant’ eran li occhi miei fissi e attenti a disbramarsi la decenne sete, che li altri sensi m’eran tutti spenti. Ed essi quinci e quindi avien parete di non caler — così lo santo riso a sé traéli con l’antica rete!—; quando per forza mi fu vòlto il viso ver’ la sinistra mia da quelle dee, perch’ io udi’ da loro un «Troppo fiso!» (Purg. 32.1-9)

My eyes were so insistent, so intent on finding satisfaction for their ten- year thirst that every other sense was spent. And to each side, my eyes were walled in by indifference to all else (with its old net, the holy smile so drew them to itself), when I was forced to turn my eyes leftward by those three goddesses because I heard them warning me: “You stare too fixedly.”

This reprimand does not mean that the pilgrim is doing something “wrong” per se; what there is of wrong is in the lack of transition, for the time has come to turn his attention from the beauty of his lady back to the events unfolding in front of him.

The significance of the transition is marked in strongly autobiographical language: Dante’s eyes are fixed and intent (“fissi e attenti” [1]) because of their need to “quench the desire” (“disbramarsi”) of their “ten-year thirst” (“la decenne sete” [2]). The result is that all his senses other than sight are spent and that his eyes are indifferent to all but Beatrice, whose “holy smile drew them to her with the ancient net”: “così lo santo riso /a sé traéli con l’antica rete!” (5-6).

Here the poetic force is in the resurgent presence of eros in the tones of the lyric love repertory (“l’antica rete” is not coincidentally a favorite of Petrarca’s), tones that at the same time are strangely mixed with the theological (“lo santo riso”). This fusion is a harbinger of Paradiso and its descriptions of Beatrice.

Indeed, this passage as a whole anticipates the many passages in Paradiso in which Dante’s gaze is converted from Beatrice to the heavens, and then back from the heavens to Beatrice. Neither gaze is wrong per se, but rightness is in the dialectical dance of the gaze, which registers the incrementality of conversion.

From Purgatorio 30’s focus on three irreducible incarnate historical essences, and its signature inscription of individual historicity through names — “Dante, perché Virgilio se ne vada” and “Ben son, ben son Beatrice” (Purg. 30.55 and 73) — we transition in Purgatorio 32 to the history of the universal Church.

Of course, Dante has managed to blur productively the distinction between the historicity of irreducible and embodied beings (Virgilio, Dante, Beatrice) and the history of the universal Church by making the Word of God (the books of the Bible) take the form of embodied persons. As discussed in the Commento on Purgatorio 29, where the procession first takes place: “Dante reproduces the Bible not as words but as things; the one text whose verba are in fact res are preserved by him as res in his verba (The Undivine Comedy, p. 155).

In effect, when the procession of the books of the Bible comes into our view in Purgatorio 29 as embodied figures, Dante is signalling that he is representing the only verbal medium — the Bible, the “word” of God — whose literal level is historical. The Bible is the only verbal medium whose signa are res, whose literal level is not fiction but truth. However, Dante has to accomplish this representation within his own verbal medium of the Commedia. In other words, he has to make God’s res into signa in his text. Hence the trope of embodied figures for the books of the Bible.

For Dante does not have the ability to use signs that are things. He can only gesture at doing so, as he does brilliantly on occasions throughout the Commedia, in most concentrated form on Purgatorio’s terrace of pride. So doing, he brings into contact the two modes of signifying: figural allegory (in which the literal/historical is true) and personification allegory (in which it is not).

We shall see the staged — and surreal — proximity of figural allegory and personification allegory performed by the narrator of the Commedia at the end of this canto. This moment constitutes one of the poem’s most distilled mise-en-abyme of the Commedia’s mode of signifying.

* * *

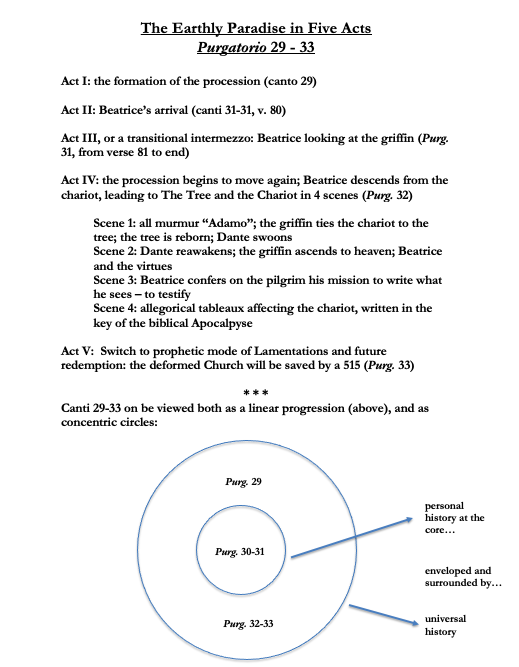

There are two outlines attached in this Commento to Purgatorio 32. One is the linear outline, “The Earthly Paradise in Five Acts”, also available in the Commento to Purgatorio 29. I offer it again now as the reader may find further consultation at this point useful:

We are now in Act IV of the Earthly Paradise. As the above outline indicates, Act IV can be further subdivided into ‘The Tree and the Chariot in Four Scenes”. Scenes 1, 2, and 3 relate the various interactions between the griffin, Beatrice, and Dante. Scene 3 culminates when Beatrice confers upon Dante-pilgrim his mission to bear witness to what he sees in the Earthly Paradise, to testify. Scene 4 immediately transitions to that which Dante-pilgrim must witness, namely the historical travails visited upon the Church.

These travails are outlined in the second attachment, “Events of Purgatorio 32 and Tableaux Depicting the History of the Church”, found at the end of this Commento. Here Dante-poet narrates what he sees as the many persecutions of the Church in the key of the biblical Apocalypse.

With respect to the events that unfold in Purgatorio 32, we come back to the issue of the representation of representations, and thus to the merging of figural and personification allegory. As I wrote in The Undivine Comedy: “Purgatorio 32’s symbolic dramatizations of the afflictions of the Church constitute the Purgatorio’s final series of representations of representations” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 158).

Let us return to the intersection in the canti of the Earthly Paradise of the Commedia’s two modes of allegory: the dominant figural allegory, in which the literal level is treated as historical and true, in these canti encounters and even merges with the less frequent use of personification or quid pro quo allegory. In The Undivine Comedy I note that “the apocalyptic allegories of canto 32 are mixed with elements of Dante’s figural allegory to forge a mode that is bizarrely and uniquely Dantesque”:

How can Beatrice both be “my lady” and also drive off the fox of heresy? How can the harlot who personifies the Church incite the giant to jealousy by looking at Dante? The poet breaks the frame of his symbolical dramas by inserting the first person singular of the figural mode, first calling Beatrice “la donna mia” in Purgatorio 32.122, then having the harlot turn her lascivious gaze to me — “a me” in 32.155. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 158)

Dante thus causes the two types of allegory to intersect and creates an emblem for the Commedia’s trademark intersecting of the universal with the singular, of the macrocosm with the microcosm.

In this canto Dante scripts a performance of God’s role in human history. The first performance, in Purgatorio 32.37-60, depicts Adam’s sin and fall and Christ’s redemption of mankind.

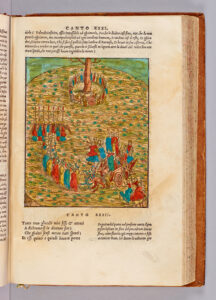

Beatrice is now in the chariot at the center of the procession, the chariot that was empty when the procession first came into view. We recall that the chariot is surrounded by the four animals representing the Gospels, who are further surrounded by the personified books of the Bible. See the schematic drawing of the procession in the Commento to Purgatorio 29.

At this point, the entire procession wheels around and turns east; Matelda, Dante, and Stazio follow the chariot with Beatrice in it (Purg. 32.28-30). After they travel the distance of three flights of an arrow, Beatrice descends from the chariot (Purg. 32.34-36). Dante now hears a general murmuring of the name “Adamo” as everyone circles around a tree that has been stripped of its leaves and flowers (Purg. 32.37-39).

This tree is inverted like the trees on the terrace of gluttony; in fact, this is the very tree from which those trees were grafted.

Now Dante sutures the events on the terrace of gluttony, for instance the examples that underline the transgression of eating from the inverted tree, to the events in the Earthly Paradise. For the griffin (who is pulling the chariot) is congratulated by everyone precisely for not having eaten from this tree:

Beato se’, grifon, che non discendi col becco d’esto legno dolce al gusto, poscia che mal si torce il ventre quindi. (Purg. 32.43-45)

Blessed are you, whose beak does not, o griffin, pluck the sweet-tasting fruit that is forbidden and then afflicts the belly that has eaten!

In other words, the griffin-Christ is congratulated for not having transgressed, for not having done what Adam and Eve did.

This is the tree from which Adam and Eve ate. The sin of gluttony thus reaches its full metaphorical potential, given that the eating that is castigated here is not literal but supremely metaphorical: Adam and Eve ate of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

In The Undivine Comedy I attempt to show how in this passage Dante ties together all his threads, connecting his personal emblem of transgression, Ulysses, to the biblical story of transgression:

Here we find the Purgatorio’s ultimate synthesis of the Ulyssean model (a man — in this case Dante — tempted by sirens) with Augustine’s critique of false pleasure. Given that the sirens of verse 45 may be interpreted in the light of Cicero’s De Finibus as knowledge, resistance to the sirens constitutes not only resistance to the false pleasures of the flesh but also resistance to the false lure of philosophical knowledge, a lure embodied in Dante’s earlier itinerary by the donna gentile/Lady Philosophy of the Convivio, the text that begins with the Ulyssean copula of desire and knowledge: “tutti li uomini naturalmente desiderano di sapere.”

As the pilgrim has learned restraint before the sweet siren in all her guises, so, in the earthly paradise, the griffin is praised for having resisted the sweet taste of the tree of knowledge: “Beato se’, grifon, che non discindi / col becco d’esto legno dolce al gusto, / poscia che mal si torce il ventre quindi” (Blessed are you, griffin, who do not tear with your beak from this tree sweet to the taste, for by it the belly is evilly twisted [Purg. 32.43-45]). By resisting the temptation of knowledge, the griffin refuses to challenge God’s interdict: the interdetto of Purgatorio 33.71, where the tree is glossed precisely in terms of the limits it represents, the obedience it exacts, and the consequent justice of the punishment meted to those who transgress. The temptation to which Adam/Ulysses succumb is the temptation that the griffin resists. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 108)

In scene 1 of Act IV, the griffin drags the chariot to the dead tree, and ties the one to the other. The tree comes back to life, a rebirth described with the same metaphoric language that will be used for the reborn Dante at the end of Purgatorio:

Come le nostre piante, quando casca giù la gran luce mischiata con quella che raggia dietro a la celeste lasca, turgide fansi, e poi si rinovella di suo color ciascuna, pria che ’l sole giunga li suoi corsier sotto altra stella; men che di rose e più che di viole colore aprendo, s’innovò la pianta, che prima avea le ramora sì sole. (Purg. 32.52-60)

Just like our plants that, when the great light falls on earth, mixed with the light that shines behind the stars of the celestial Fishes, swell with buds—each plant renews its coloring before the sun has yoked its steeds beneath another constellation: so the tree, whose boughs—before—had been so solitary, was now renewed, showing a tint that was less than the rose, more than the violet.

Dante now falls asleep, in a sleep that is described in a manner that has interesting repercussions for the concept of a visionary “waking sleep”. We noted in the earlier procession that the personified Book of the Apocalypse at the end of Purgatorio 29 is one who walks “dormendo, con la faccia arguta” (Purg. 29.144). Now we come again to the topic of sleep, and to the aphasia that overcomes the poet.

Dante wishes he could find the “essempro” — the model from life — that would allow him to depict the act of his falling asleep: “come pintor che con essempro pinga, / disegnerei com’io m’addormentai” (I’d draw the way in which I fell asleep [Purg. 32.68]). Because he cannot find the model he needs, he is forced to pass on, to “jump,” to leave a dropped stitch in the fabric of his narrative: “Però trascorro a quando mi svegliai” (Therefore I pass on to when I awoke [Purg. 32.70]). As I write in The Undivine Comedy:

If narrative has power — Mercury’s words put Argus to sleep, Christ’s word awakened his disciples — it also has limits. This jump, this trascorrere of the narrative line because it has reached an event for which it can find no adequate signifier, anticipates a narrative condition that typifies the Paradiso. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 163)

When Dante awakens, in scene 2 of Act IV, the whole company of angels and books of the Bible is ascending to heaven following the griffin that symbolizes Christ. They leave as custodians of the renewed tree only Beatrice with the seven maidens who symbolize the four cardinal and the three theological virtues. These are the ladies who were first represented as dancing around the empty chariot in Purgatorio 29.

In scene 3, Beatrice addresses Dante, telling him of his destiny and his obligation to write what he is shown (Purg. 32.100-105). There follows, in scene 4, the series of allegorical “performances” that dramatize the history of the Church (the chariot). These allegorical tableaux are performed for Dante to witness and to write down:

1) the persecutions of the Church by the early emperors (the eagle);

2) the early heresies, overcome by the Church (the fox driven away by Beatrice);

3) the Church’s acquisition of temporal possessions through the Donation of Constantine (the eagle’s feathers fall on the chariot; see the Commento on Inferno 19);

4) the great schism by which the Church was rent (the dragon representing Islam; see the Commento on Inferno 28);

5) the further accession of wealth and power that utterly distorts and deforms the original character of the Church;

6) the Church disfigured by the seven deadly vices that afflict it in its corruption; it becomes the monster of the Apocalpyse (this whole section is Dante’s own personal version of the Apocalpyse);

7) the Avignon Captivity: the transferral of the Church from Rome to Avignon in 1309. Beatrice is replaced in the chariot by a whore guarded by a giant, who drags the chariot away.

Canto 32, Dante’s personal “Apocalypse Now”, is the longest canto in the poem.

Return to top

Return to top