This canto begins with some of the Commedia’s most obscure and prophetic diction, again written under the sign of the Apocalpyse. When John of Patmos wrote the Apocalpyse he used the figure of the “magna meretrix” — “great whore” — as a way of representing Rome and the corruption of the Roman Empire. In other words, the text was politically motivated, and allegory was used as a covert but powerful way of resisting the evils of the Roman Empire. The Apocalpyse was used for similar political purposes in the Middle Ages, but the medieval target was no longer the defunct Roman Empire but the powerful and corrupt Roman Church.

Dante was not the first to use the whore of the Apocalpyse to signify the Church; by using this imagery he shows his willingness to engage some of the most radical and anti-ecclesiastical writings then in circulation. The rebellious theologians who used the imagery of the Apocalypse to indict the Church were mainly so-called “Spiritual Franciscans,” the super-zealous reformist wing of the Franciscan order that was persecuted and eventually driven out of Italy by the papacy and the established Church.

In the prophecy of Purgatorio 33 Beatrice provides an obscure gloss to the whore and the giant who close off the tableaux vivants of the previous canto. The core of her prophecy (Purgatorio 33.37-45) alludes to the coming of a secular ruler, the heir of the eagle (see verses 37-38), who will kill the prostitute and the giant:

Non sarà tutto tempo sanza reda l’aguglia che lasciò le penne al carro, per che divenne mostro e poscia preda; ch’io veggio certamente, e però il narro, a darne tempo già stelle propinque, secure d’ogn’intoppo e d’ogni sbarro, nel quale un cinquecento diece e cinque, messo di Dio, anciderà la fuia con quel gigante che con lei delinque. (Purg. 33.37-45)

The eagle that had left its plumes within the chariot, which then became a monster and then a prey, will not forever be without an heir; for I can plainly see, and thus I tell it: stars already close at hand, which can’t be blocked or checked, will bring a time in which, dispatched by God, a Five Hundred and Ten and Five will slay the whore together with that giant who sins with her.

Very famous and mysterious is the verse in which Beatrice refers to the coming savior as a “Five Hundred and Ten and Five”: “cinquecento dieci e cinque” (Purg. 33.43). Many over the centuries have tried to decipher the meaning of the reference to 500, 10, and 5! The interpretation that has gained most traction is the one that substitutes Roman numerals — D for 500, X for 10, and V for 5 — and then scrambles them to spell DVX or DUX: the Latin for “leader”.

Beatrice also thematizes prophecy as a narrative genre, one that is bound up with necessary obscurity. It is fascinating that Dante is so clear and transparent about a genre in which he — like the prophets he emulates — is necessarily dark and obscure:

E forse che la mia narrazion buia, qual Temi e Sfinge, men ti persuade, perch'a lor modo lo ’ntelletto attuia... (Purg. 33.46-48)

And what I tell, as dark as Sphinx and Themis, may leave you less convinced because—like these— it tires the intellect with quandaries...

Beatrice shows quite a lot of awareness of the power of narrative in this passage: she uses the word “narrazion” in Purgatorio 33.46 — a hapax in the Commedia — to refer to her own discourse, putting the poet in the position of narrating her narration. Purgatorio 33’s lexicon is saturated with metapoetic terminology: besides the poem’s only use of narrazione and one of seven uses of narrare, it is one of few cantos in which segnare is used twice, and the only canto in Inferno or Purgatorio in which scrivere occurs more than once. In fact it is used thrice.

Beatrice instructs Dante that when he returns to earth it will be his job to write down the visions that he has seen while in the Earthly Paradise:

Tu nota; e sì come da me son porte, così queste parole segna a’ vivi del viver ch’è un correre a la morte. (Purg. 33.52-54)

Take note; and even as I speak these words, do you transmit them in your turn to those who live the life that is a race to death.

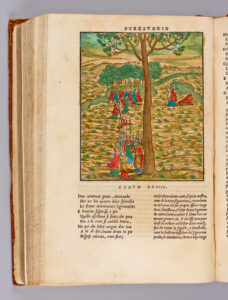

Dante’s obligation to write what he has seen requires him to pay particular attention to what occurred to the tree (“pianta” of Purg. 33.56) that has been twice despoiled: first by Adam, and subsequently by the historical vicissitudes of the Church. Beatrice now glosses the tree, thus offering an interpretation of the events of the previous canto. She says that the tree that was dead and then restored to life represents “la giustizia di Dio, ne l’interdetto” (Purg. 33.71): literally, God’s justice in his interdict.

It is worth noting that “interdict” is a juridical term, associated with canon law, where it refers to an ecclesiastical ban or prohibition: “An interdict is a censure, or prohibition, excluding the faithful from participation in certain holy things, such as the Liturgy, the sacraments, (excepting private administrations of those that are of necessity), and ecclesiastical burial, including all funeral services” (Wikipedia).

So, how should we construe “God’s justice in his interdict”? God had placed an interdict — a ban or prohibition — on humanity, and had marked the point that humanity was forbidden to trespass. When we trespassed nonetheless, what resulted was God’s justice.

We recall that the griffin is praised by all in attendance around the chariot in Purgatorio 32 because it resists eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, resists the temptation of knowledge, and refuses to challenge God’s interdict. The griffin resisted the lure of trespass: a lure that was instead embraced by Lucifer, by Nembrot, by Adam. Those are the legitimate biblical examples of trespass, to which Dante adds his own personal example: the Greek adventurer, Ulysses.

The tree is glossed in Purgatorio 33 precisely in terms of the limits it represents, the obedience it exacts, and the consequent justice of the punishment meted to those who transgress.

In other words: because there was a clear prohibition stating that it was off limits to eat of the tree of knowledge, and because Adam and Eve did not heed the prohibition, because they freely transgressed, the suffering that they incurred was just.

The insufficiency of Dante’s understanding is also a topic of discussion (Purg. 33.85-90). This topic prepares us for Paradise, for the journey of Paradiso trains the intellect, as the journey of Purgatorio trains the will. Dante asks Beatrice why it is that he doesn’t understand what she says (Purg. 33.82-84). In reply she explains that his inability to understand her reveals the limitations of “that school that you followed”, whose doctrine is so insufficient compared to that which she will teach him: “«Perché conoschi», disse, «quella scuola / c’hai seguitata, e veggi sua dottrina / come può seguitar la mia parola»” (“That you may recognize,” she said, “the school that you have followed and may see if its doctrine can comprehend what I have said” [Purg. 33.85-87]).

While Chiavacci Leonardi references Averroism as the mistaken “dottrina” that Dante has in mind in this passage, I believe the indictment is more generic, embracing all the mistaken philosophical and doctrinal views of Dante’s past. The Paradiso will feature corrections of previous positions that Dante had taken, not involving Averroism.

Dante tells Beatrice that he doesn’t remember ever having been estranged from her: “Non mi ricorda / ch’i’ stranïasse me già mai da voi, / né honne coscïenza che rimorda” (I don’t remember making myself a stranger to you, nor does conscience gnaw at me because of that [Purg. 33.91-93]). Beatrice explains that this is because he has already drunk of Lethe and thereby forgotten his transgressions. This passage is a final reminder of the personal rebuke that makes up the central core of the canti of the Earthly Paradise, and that can be distilled in Beatrice’s accusation of Purgatorio 30: “questi si tolse a me, e diessi altrui” (“he took himself from me and gave himself to another [Purg. 30.126]).

The charge that dominates Purgatorio 30 and 31 is now recalled and dramatized by the poet; it is recalled, very cleverly, by staging Dante-protagonist’s oblivion. Dante’s turning away from Beatrice and his former pledging of himself to another are evoked by his having forgotten that there were any such occurrences! Beatrice summarily concludes that Dante’s oblivion of estrangement is the proof that the estrangement occurred: “cotesta oblivïon chiaro conchiude / colpa ne la tua voglia altrove attenta” ( we can conclude from this forgetfulness the fault in your will elsewhere intent [Purg. 33.98-99]).

“Colpa ne la tua voglia altrove attenta” (the fault in your will elsewhere intent [Purg. 33.99]) is a lapidary summation of the Purgatorio’s chief task: to make sure that a will that is elsewhere intent — a voglia that is altrove attenta in the language of this canto — be properly redirected. A will that is twisted must be torqued until it is straightened. This is the message of the presence of the verb torcere in the Purgatorio, in the present “torce” and the past participle “torta”.

We recall that Dante’s drinking of Lethe had occurred in the latter part of Purgatorio 31; after Beatrice accuses Dante of deviating from her and he has confessed (Purgatorio 30-31), she instructs Matelda to bathe him in the river of forgetfulness (Purg. 31.94 and following). Now, in the last section of Purgatorio 33, there will be an immersion in the other river of the Earthly Paradise: Eunoè.

The two immersions are sequential for all souls: we must be granted oblivion of our sins before our good memories are restored. For Dante alone the two immersions are separated by the magnificent tableaux vivants of Purgatorio 32.

At this point Dante begins to wrap up the final business of his account of Purgatory. The two rivers Eunoè and Lethe are compared to the Tigris and Euphrates (Purg. 33.112-14), reminding us of the Mesopotamian origins of biblical Eden. Matelda — now named for the first and only time, in Purgatorio 33.119 — functions as a kind of priestess responsible for taking Dante and Stazio to bathe in Eunoè.

Dante reminds us that Stazio is still present for the last time in Purgatorio 33.134. Since Dante-pilgrim’s experience is unique, Stazio serves as an important marker for what a “regular” saved soul would do in Eden. After a final purgatorial address to us, the readers, the cantica concludes with verses that describe Dante as:

rifatto sì come piante novelle rinovellate di novella fronda, puro e disposto a salire alle stelle. (Purg. 33.143-45)

remade, as new trees are renewed when they bring forth new boughs, I was pure and prepared to climb unto the stars.

The emphasis on “new trees” — piante novelle” — that have been renewed with new leaves reminds us of the tree in Eden that was defoliated by Adam’s sin and then renewed by the griffin-Christ. Similarly, all souls who complete purgation are renewed in Christ. The pilgrim is “puro” because he is cleansed of vice, the disposition to sin, and he is “disposto” because his will — the part of us that disposes or not to do something — has been made willing and ready. Dante is reborn, new again. He is ready for the final leg of his journey.

Return to top

Return to top