We recall from Purgatorio 10 that the sculptural art the pilgrim sees engraved on the walls of purgatory is so “real” that it seems alive: Dante feels the wind moving in Trajan’s banners, he smells the incense, he hears the spoken words exchanged between Trajan and the widow. Ultimately Dante confirms that this is God’s art, and calls it “visibile parlare” — visible speech — in Purgatorio 10.95.

Essentially Dante devises in Purgatorio 10 a way of describing moving images in words: he is describing moving pictures/movies/film, though the medium does not yet exist. The same miraculous medium is used for the thirteen examples of punished pride that are described in Purgatorio 12. While the carved examples of the virtue of humility are on the wall of the terrace, the examples of the vice of pride are on its pavement, like pavement tombs the pilgrim has seen on earth, but more lifelike due to the “artificio” — artifice (Purg. 12.23) — of their maker.

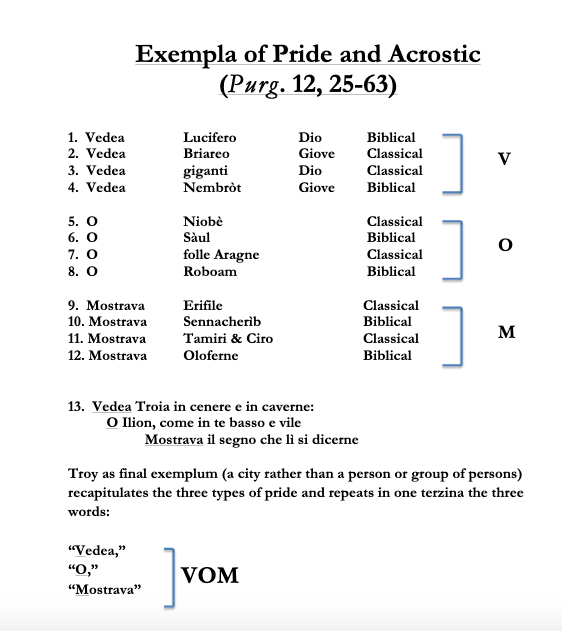

A spectacular acrostic displays the thirteen examples of pride almost “visually”: letters are deployed as a kind of artwork. The examples are arranged in the following pattern: four sets of terzine begin with the word “Vedea”; four sets of terzine begin with the word “O”; four sets of terzine begin with the word “Mostrava”. Thus twelve examples of pride spell out VOM or UOM, “man” in Italian, signifying that pride is mankind’s besetting sin. Here is an attached chart that offers a list of all the examples.

The thirteenth terzina offers the final example, which sums up all the others by referring to a city rather than to a person and by replicating in one terzina all three of the letters that spell the acrostic:

Vedeva Troia in cenere e in caverne; o Ilión, come te basso e vile mostrava il segno che lì si discerne! (Purg. 12.61-63)

I saw Troy turned to caverns and to ashes; O Ilium, your effigy in stone— it showed you there so squalid, so cast down!

The characters featured as examples of pride would repay lengthy discussion. Here we find Nembrot, he who built the tower of Babel and who spoke gibberish — non-sense — to Dante and Virgilio in Inferno 31. Nembrot, with Ulysses, is an avatar of transgression whose name is rehearsed in each of the three cantiche:

Vedea Nembròt a piè del gran lavoro quasi smarrito, e riguardar le genti che ’n Sennaàr con lui superbi fuoro. (Purg. 12.34-36)

I saw bewildered Nimrod at the foot of his great labor; watching him were those of Shinar who had shared his arrogance.

Most important to my reading of the terrace of pride is the mythological figure of Arachne, marked by the Ulyssean adjective “folle”:

O folle Aragne, sì vedea io te già mezza ragna, trista in su li stracci de l’opera che mal per te si fé. (Purg. 12.43-45)

O mad Arachne, I saw you already half spider, wretched on the ragged remnants of work that you had wrought to your own hurt!

Arachne was famous for her weavings that were so lifelike that they seemed alive. The passage describing her work in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, discussed in Chapter 6 of The Undivine Comedy, nourished Dante in conceptualizing representational arrogance as the cornerstone of his terrace of pride. Again, as in Purgatorio 10’s depiction of the “visibile parlare” of the sculpted virtues, in Purgatorio 12 the point is hammered home that this art is not just “life-like”. It is “life” itself:

Morti li morti e i vivi parean vivi: non vide mei di me chi vide il vero, quant’io calcai, fin che chinato givi. (Purg. 12.67-69)

The dead seemed dead and the alive, alive: I saw, head bent, treading those effigies, as well as those who’d seen those scenes directly.

At the end of the canto we encounter another of the ritual components of the purgatorial experience, repeated on each terrace: Dante meets an angel and a “P” (for peccato, sin) is removed from his brow, signifying his successful participation in the process of purgation. As a result of his time on the terrace of pride, the pilgrim has purged one of the seven deadly sins (more properly, vices). We note that he does not need to participate in the suffering assigned to the souls on this terrace: he is not bent under heavy rocks. As in Hell, his participation is a form of observation and meditation. Unlike Hell, he will return to Purgatory, and so will have the opportunity to participate more fully than he does now.

The travelers climb toward the next terrace, and as they climb they hear a shortened form of the first Beatitude: “Beati pauperes spiritu” (Matthew 5:3). The eight Beatitudes are from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:3-10) and will be featured on the purgatorial terraces. In full, this Beatitude is: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” It is featured on the terrace of pride to celebrate the soul’s new acquisition of a pride-less “poverty of spirit.”

Return to top

Return to top