The pilgrim now asks Cacciaguida about the prophecies that were made to him in the course of his journey, by fellow Florentines: Ciacco in Inferno 6, Farinata in Inferno 10, and Brunetto Latini in Inferno 15. All offer him prophecies of the exile and disgrace that await him.

Dante was exiled from Florence, we recall, in 1302, two years after the journey to the afterlife in Easter week of 1300. Hence, the poet communicates the information about his exile in the form of prophecies — warnings (intended to be helpful, in the case of Brunetto, or vengeful, in the case of Farinata), which are passed on to him by Florentines and other Italians whom he meets.

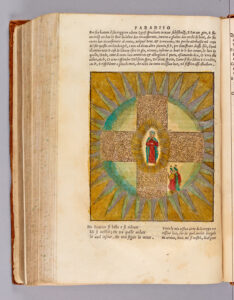

The heaven of Mars, as we have seen, celebrates family lineage and family ties: mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, wives, husbands, children. The female side of the lineage is not absent: Cacciaguida refers to “mia madre, ch’è or santa” (my mother, blessed now) in Paradiso 16.35 and explains that the Alighieri surname comes from his wife, “mia donna venne a me di val di Pado, / e quindi il sopranome tuo si feo” (my wife came from the valley of the Po; the surname that you bear was brought by her) in Paradiso 15.137-38.

But most of all this heaven celebrates fathers. And thus it is not altogether surprising to find that the pilgrim, in describing to his great-great-great-grandfather the journey through the afterlife in which he learned of his future exile, uses the name “Virgilio”. Here, for the first time since Purgatorio 30, we encounter the name of the Roman poet who was the pilgrim’s surrogate father through much of his journey:

mentre ch’io era a Virgilio congiunto su per lo monte che l'anime cura e discendendo nel mondo defunto, dette mi fuor di mia vita futura parole gravi . . . (Par. 17.19-23)

while I was in the company of Virgil, both on the mountain that heals souls and when descending to the dead world, what I heard about my future life were grievous words . . .

In initiating his explanation of future events, Cacciaguida takes the profoundly historicized family motif of the heaven of Mars and metaphorizes it. Instead of a real historical mother or stepmother, he now refers to a “perfidious stepmother” in metaphorical — allegorical — sense, referring to the perfidious forces that led to Dante’s exile. The “spietata e perfida noverca” (fierce and faithless stepmother) of Paradiso 17.47 recalls the use of “noverca” in Paradiso 16, where it refers to the Roman Curia: “Se la gente ch’al mondo più traligna / non fosse stata a Cesare noverca” (If those who, in the world, go most astray / had not seen Caesar with stepmothers’ eyes [Par. 16.58-59]).

The implication in Paradiso 17 is that Dante’s exile comes about through the machinations of the papal court and Pope Boniface VIII. Given that the Pope supported the Black Guelphs, and that Dante was exiled with his fellow White Guelphs when the Blacks took power, this is a valid claim. This view of events also echoes the first discussion of Dante’s exile, in Inferno 6.

In Paradiso 17 Dante not only metaphorizes the family motif; he also makes it negative. Thus, he compares Dante to the innocent Hippolytus, betrayed by his stepmother Phaedra, and announces that Dante’s ruin will also come about because of a wicked stepmother:

Qual si partio Ipolito d’Atene per la spietata e perfida noverca, tal di Fiorenza partir ti convene. Questo si vuole e questo già si cerca, e tosto verrà fatto a chi ciò pensa là dove Cristo tutto dì si merca. (Par. 17.46-51)

Hippolytus was forced to leave his Athens because of his stepmother, faithless, fierce; and so must you depart from Florence: this is willed already, sought for, soon to be accomplished by the one who plans and plots where—every day—Christ is both sold and bought.

Cacciaguida then proceeds to tell the pilgrim of the loss and alienation that his exile will bring about:

Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta più caramente; e questo è quello strale che l’arco de lo essilio pria saetta. Tu proverai sì come sa di sale lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle lo scendere e ’l salir per l’altrui scale. (Par. 17.55-60)

You shall leave everything you love most dearly: this is the arrow that the bow of exile shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste of others’ bread, how salt it is, and know how hard a path it is for one who goes descending and ascending others’ stairs.

The poigancy of these famous verses is guaranteed by our knowledge that the man who wrote them had already endured the sufferings that they recount — indeed, he had endured them for many long years. He was not imagining; he knew whereof he wrote. With great lucidity, Dante examines the feelings of loss that he experienced.

The first arrow shot from the bow of exile is affective and all-encompassing. He will leave behind all that he holds most dear: “ogne cosa diletta / più caramente” (everything you love most dearly [Par. 17.55-56]). The second and third arrows hit home in a way that is less about affect and feeling, and more primal, more in the gut. They involve the degradation of being constrained to depend on others — note the repetition of “altrui” — for the primal human needs of food and shelter: he will experience the bitter taste of “others’ bread” (“lo pane altrui” [Par. 17.59]) and the hardship of “others’ stairs” (“l’altrui scale” [Par. 17.60]).

Exile will also bring Dante the mortification of finding that his companions in exile, his fellow Whites, turn against him, showing him utter ingratitude (“tutta ingrata” [Par. 17.64]).

But there will be, if not solace, at least a harbor in the storm, a “refuge” offered by the della Scala family, lords of Verona:

Lo primo tuo refugio e ’l primo ostello sarà la cortesia del gran Lombardo che ’n su la scala porta il santo Uccello; ch’in te avrà sì benigno riguardo, che del fare e del chieder, tra voi due, fia primo quel che tra li altri è più tardo. (Par. 17.70-75)

Your first refuge and your first inn shall be the courtesy of the great Lombard, he who on the ladder bears the sacred bird. And so benign will be his care for you that, with you two, in giving and in asking, that shall be first which is, with others, last.

For a prickly and defensive man like Dante, who feels acutely the discomfort of taking that which is given by “others” (“lo pane altrui” and “l’altrui scale”), as compared to that which is earned for oneself or provided by one’s own family’s fortune, there is no greater compliment in the social sphere than the one he pays here: Bartolomeo della Scala is a host who gives before being asked, not subjecting Dante to the humiliation of the request.

Important in this context is the opening section of Epistola 13, the Letter to Cangrande della Scala, in which Dante theorizes the possibility of friendship between unequals. Dante’s shame at the disgrace of exile exacerbates his already keen sense of social disparity, shown in his early pre-exile awareness of the distance between himself and his friends who belong to rich and powerful magnate families. I touch on this issue in the essay “Aristotle’s Mezzo, Courtly Misura, and Dante’s Canzone Le dolci rime: Humanism, Ethics, and Social Anxiety”, cited in Coordinated Reading. See too the Commento on Inferno 16, where I note: “Dante’s sensitivity to the ‘nuova gente’ would undoubtedly have been exacerbated by the decline of his family’s fortunes, a decline traced by Enrico Faini in ‘Ruolo sociale e memoria degli Alighieri prima di Dante,’ cited in Coordinated Reading. As Faini shows, Dante’s ancestors had achieved aristocratic status in the time of Cacciaguida and Alighiero I, while Dante’s branch of the family lost noble standing in the succeeding decades” (par. 29).

Dante has a long history, by the time he writes Paradiso 17, of bringing into balance what he experienced as his social inferiority by means of the immense social capital generated by his writing and his intellectual attainments. Dante’s own family, although gentile in a minor sort of way, was not wealthy or important: it is a family we know of because of Dante himself. And he makes the same move now, bringing this canto of exile and disgrace to a close with his anointment as an epic poet by his own knighted ancestor, Cacciaguida.

The pilgrim asks his ancestor to guide him as a poet: his problem is how to weigh present popularity against future fame. In the course of his journey he has seen that which, in the recounting, will be quite unpleasant to the taste. And yet, if he does not recount what he has witnessed, he fears that he will lose long “life” — “vivere”, in other words fame and longevity as a poet — among the readers of the future:

e s’io al vero son timido amico, temo di perder viver tra coloro che questo tempo chiameranno antico. (Par. 17.118-20)

yet if I am a timid friend of truth, I fear that I may lose my life among those who will call this present, ancient times.

Dante is here writing about the readers of the future — in other words, he is writing about us. We are those who refer to 1300 as ancient: “coloro / che questo tempo chiameranno antico” (those who will call this time ancient [Par. 17.119-20).

The answer is a trumpet blast of clarity. Tell everything you have seen, says Cacciaguida: “tutta tua vision fa manifesta” (let all that you have seen be manifest [Par. 17.128]).

There are several points I would like to make here. One is that Cacciaguida suggests that Dante’s journey has been engineered (by Whom?) in order to make his vision more compellingly pedagogic. He has been shown famous souls because in this way the encounters he recounts will be exemplary and more didactically powerful:

Però ti son mostrate in queste rote, nel monte e ne la valle dolorosa pur l’anime che son di fama note . . . (Par. 17.136-38)

Therefore, within these spheres, upon the mountain, and in the dismal valley, you were shown only those souls that unto fame are known . . .

It is important to point out that Cacciaguida’s remark is, as I note in Dante’s Poets, “patently untrue”. For, “most of the souls Dante meets we would never have heard of were it not for his poem” (Dante’s Poets, p. 282). For instance, Francesca da Rimini would have been lost to history were it not for Dante, who gave her historical life. There are souls like Virgilio, famous before he entered Dante’s poem, and there are souls like Francesca:

They are famous now because the text has given them life, making them into the kinds of exemplary figures whom Cacciaguida describes; Cacciaguida’s assertion, untrue when it was written, is true now, because the text has made it true. (Dante’s Poets, p. 282)

So here again, in this canto of his poetic investiture, we find Dante conflating life and text. He goes back to one of his oldest poetic tropes, that of writing down faithfully what life offers him (see the “book of memory” at the beginning of the youthful Vita Nuova). And in this case Cacciaguida retrofits the souls whom the pilgrim has actually encountered in order to make them fit an exemplary model that is appropriate for an epic poem.

Let me end this commentary on the heroic note sounded by this page in The Undivine Comedy:

In these cantos of the Paradiso, Dante explores the ancient epic function of the poet who does not attenuate or flinch from the sorrows of the history he records but who yet invokes time’s consolations — fame and memory — to counter time’s scissors and their bitter corollary, the fact that “Le vostre cose tutte hanno lor morte.” That all our things have their death is the fact that epics never forget (and with which they end: Hector’s death, Turnus’s death, Beowulf’s death, Rodomonte’s death), the fact that — in the gesture that makes them “epic” — they heroically and flimsily deny with words, the words that give life not only to the song but to the singer. In epic fashion, Dante must tell the truth, because otherwise he fears to lose his future life among us, his readers, the ones who will call his time ancient: “temo di perder viver tra coloro / che questo tempo chiameranno antico” (Par. 17.119-20). And, true to the epic key of these cantos, Cacciaguida does not reprove the pilgrim for desiring life — “viver” — through his literary prowess; rather he incites him to tell the truth and provides him the literary formula most likely to guarantee his future life in words. The very coinage infuturarsi, used by Cacciaguida to refer to the pilgrim’s future life in words, echoes the coinage etternarsi of the Brunetto episode; but the Paradiso does not conform to the theological grid by confirming the vanity of literary immortality, the Inferno’s suggested impossibility of living in a text. Instead, these epic cantos recast Brunetto’s message, empowering the poet to live in his words, among those “che questo tempo chiameranno antico.” Nor does this poet grow indifferent to posterity’s mandate; in the Commedia’s final canto, in a final epic surge, Dante still prays to be able to reach “la futura gente” with his poetry: “e fa la lingua mia tanto possente, / ch’una favilla sol de la tua gloria / possa lasciare a la futura gente” (and make my tongue so powerful that one spark alone of your glory it may leave for future folk [Par. 33.70-72]).

(The Undivine Comedy, p. 140)

Return to top

Return to top