- Dante’s treatment of sodomy continues to run counter to the cultural norm: Dante uses sodomy not to focus on sexual sin but as a lever for indicting the corruption of famous Florentines

- Inferno 16 undercuts the heroic patina of Inferno 15

- Social status and its signifiers (e.g. dress and deportment)

- From Inferno 6 to Inferno 15-16: the themes of civic commitment — “ben far” (6.81, Inf. 15.64) — and of important work: “dato t’avrei a l’opera conforto” (Inf. 15.60) and “l’ovra di voi e li onorati nomi” (Inf. 16.59)

- Wealth management and Florentine nobility: Inferno 16’s castigation of new money

- Dante as a political theorist of wealth and nobility beginning in the canzone Le dolci rime (circa 1294); the issue of appropriate civic behavior vis-à-vis wealth is also treated in the canzone Poscia ch‘Amor (circa 1295)

- Dante’s self-contradictions as a theorist of wealth and nobility:

- 1) In the canzone Le dolci rime (circa 1294), Dante had boldly refuted the theory that old money confers nobility. His concern was old money, not in the sense of condemning it per se, but in order to sever it from nobility.

- 2) In Inferno 16 Dante has shifted: he substitutes the temporal adjective that qualifies material possessions in Le dolci rime — “antica possession d’avere” — with the opposite temporal adjectives: “nuova” and “sùbiti”, evoking the canzone and signalling his changed perspective.

- 3) In sum, while Dante previously dismissed the idea of old money as a key feature of nobility, now he disparages new money, thus implying greater appreciation of the families characterized by their “antica possession d’avere” (ancient possession of wealth [Le dolci rime, 2])

- An extended meditation on narrative transition (as previously in Inferno 8–Inferno 9) begins in the first verse of Inferno 16 and concludes at the end of Inferno 17

- The word comedìa and the “Geryon principle” (The Undivine Comedy, 15, 59-60, 90, 98, and 271, note 33); for other examples, see Inferno 25, Inferno 28, and Inferno 34

[1] Inferno 16 continues Dante’s treatment of sodomy, which does not feature the practice of sodomy at all. Rather, we might say that “sodomy” (a favorite whipping post among the preachers of the time) is present in this ring of Hell about as much as “fornication” (another favorite whipping post) is present in Dante’s circle of lust.

[2] If we consider the treatment of sodomy among contemporary artists as well, we realize that Dante goes completely counter to the cultural norm represented, for instance, by an artist like Taddeo di Bartolo, whose sickeningly violent treatment of sodomy is reproduced in my essay “Dante’s Sympathy for the Other” (see Coordinated Reading).

[3] The graphic and violent punishment of sexual sin found in vision literature and in contemporary art, notable for its “torments directed at genitalia” (see the Commento on Inferno 15), is altogether absent from the Commedia.

[4] The sin of sodomy in Dante’s treatment seems rather to be a lever for indicting great Florentines, a way of accusing them of corrupt behavior. We thus move from a famous Florentine man of letters in Inferno 15 to famous Florentine men of public affairs in Inferno 16. All the men whom Dante places in the ring of sodomy were great citizens, considered worthy of reverence in earthly society.

[5] The treatment of the Florentine sodomites in canto 16 will have a sobering retroactive effect with respect to the great humanistic themes of canto 15. While Brunetto’s cooked visage is only touched on in passing and his physical torment glossed over in the previous canto, Inferno 16 stresses the physical torment of the sinners: “Ahimè, che piaghe vidi ne’ lor membri / ricenti e vecchie, da le fiamme incese!” (Ah me, what wounds I saw upon their limbs, / wounds new and old, wounds that the flames seared in! [Inf. 16.10-11]).

[6] Likewise, the fall from high estate and dignity is passed over in Inferno 15 and stressed in Inferno 16. The poignant simile that compares Brunetto to a runner in the footrace of Verona appears at the end of Inferno 15, allowing the poet to conclude the canto with the pathos of “e parve di costoro / quelli che vince, non colui che perde” (of those runners / he appeared the one that wins, not the one that loses [Inf. 15.123-4]). The simile does not insist on the runners’ nudity or otherwise diminish Brunetto’s dignity. In contrast, the fall from dignity of the Florentines in Inferno 16 is immediately highlighted by the simile that compares these great nobles to naked wrestlers, greased and ready for a fight: “ i campion . . . nudi e unti” (champions, naked and oiled [Inf. 16.19-24]).

[7] The issue of earthly fame, imbued with a heroic patina in Inferno 15, takes on a very different complexion when these miserable creatures speak of “la fama nostra” (our fame) in verse 31.

[8] The Florentines featured here are great citizens of the generation before Dante, the generation that included the aristocratic Florentine protagonists of Inferno 10: Farinata degli Uberti (1212-1264) and Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti (died ca. 1280). As with Brunetto Latini (1220-1294) in Inferno 15, the dramatic irony turns on what these famous souls are doing here: Guido Guerra (ca. 1220-1272), Tegghiaio Aldobrandi (died 1262), and Iacopo Rusticucci (died after 1266) are supposed to be among the noblest of the Florentines and yet here they are among the sodomites in Hell.

[9] We remember that in Inferno 6, the first canto to focus on Florence and the city’s woes, Dante asked Ciacco about a specific list of great Florentines: “Farinata e ’l Tegghiaio, che fuor sì degni, / Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo e ’l Mosca” (Farinata and Tegghiaio, who were so worthy, / Iacopo Rusticucci, Arrigo, and Mosca [Inf. 6.79-80]). The pilgrim refers to these men as citizens who did good works, who used their intellects “a ben far”, “to do good”: “ch’a ben far puoser li ’ngegni” (had their minds bent toward the good [Inf. 6.81]). Picking up the theme of ben far from Inferno 6, the works that we do in life are a key theme of Inferno 15 and 16, which offer a meditation on our civic contributions to the common good.

[10] Brunetto tells Dante that he would have supported Dante’s “opera” (work [Inf. 15.60]) had he lived, and he characterizes Dante’s own actions with the same phrase, “ben far”, that in Inferno 6 was used for the great Florentines: “ti si farà, per tuo ben far, nimico” ([the Florentine people] for your good deeds, will be your enemy [Inf. 15.64]).

[11] In these verses Dante-poet offers an endorsement of the civic virtues that he and Brunetto held dear. He also gives us a sense of his views of the inter-generational obligations that hold up a community: the obligation of the earlier generation to help and support their successors.

[12] At the same time, Dante-poet communicates the failure of the previous generation. Given that many of that prior generation’s great leaders are found in Hell, clearly the implications for the nature of the society and community that they created are dire. And indeed, with respect to the great Florentines of whose whereabouts Dante asks Ciacco in Inferno 6, we are now in a position to check off quite a few from the list: Farinata is among the heretics in Inferno 10, while Tegghiaio and Iacopo Rusticucci are here among the sodomites in Inferno 16.

[13] Like Inferno 6, Inferno 16 will treat Florentine corruption, although less through the lens of factional politics and more through the lens of the underlying greed and avarice that motivate human behavior. In other words, Inferno 16 approaches the corruption of “la nostra terra prava” — “our depraved city” [Inf. 16.9]) — through the lens of wealth acquisition and wealth management. These issues have already been treated in Inferno 7 and are deeply intertwined with the factional politics treated in Inferno 6.

[14] Accordingly, in Inferno 16 the issue of social status comes to the fore, for instance in the attention paid to dress, a very important indicator of status in Florentine society (and indeed legislated as such). While Farinata recognizes Dante as a fellow Florentine through his diction (“la tua loquela” of Inferno 10.25), these souls recognize a fellow citizen of depraved Florence through his clothing: “Sòstati tu ch’a l’abito ne sembri / esser alcun di nostra terra prava” (Stop, you who by your clothing seem to be / someone who comes from our corrupt country! [Inf. 16.8-9]). In his commentary to these verses, Boccaccio notes the local distinctiveness of civic dress: “ciascuna città aveva un suo singular modo di vestire, distinto e variato da quello delle circunvicine; per ciò che ancora non eravam divenuti inghilesi né tedeschi, come oggi agli abiti siamo” (every city had its own singular form of dress, distinct and varied from that of the surrounding towns; in that time we had not yet become English or German, as now we are in our clothing [Esposizioni sopra la Comedia di Dante, literal exposition of Inferno 16.7-9, consultable through the Dartmouth Dante Project]).

[15] Although the issue of Florence as a “terra prava” is put on the table from the very beginning of the encounter with the Florentine sodomites, and by the sinners themselves, the narrator continues to stress the high status that these sinners were accorded in society. Virgilio participates, telling his charge that these sinners must be treated with courtesy and adding, remarkably, that were it not for the nature of the place they are in (one in which fire rains down like arrows), it would be more appropriate for Dante to run toward them than for them to be running toward him: “i’ dicerei / che meglio stesse a te che a lor la fretta” (I’d say that haste / was seemlier for you than for those three [Inf. 16.17-18]).

[16] In other words, their status on earth was such that Virgilio still associates them with dignified comportment and wants to treat them with great respect. When the pilgrim learns who these souls are, the poet lets us know that his own reaction was fully in line with Virgilio’s assessment, for — says the narrator — if it had not been for the flames I would have jumped down from the bank in my eagerness to embrace these souls:

S’i’ fossi stato dal foco coperto, gittato mi sarei tra lor di sotto, e credo che ’l dottor l’avrìa sofferto. (Inf. 16.46-8)

If I’d had shield and shelter from the fire, I should have thrown myself down there among them — I think my master would have sanctioned that.

[17] These souls are still keenly aware of their own past importance in Florentine society. When the conversation moves beyond their common Florentine citizenship, Iacopo remarks that their great fame should incline Dante to speak with them: “la fama nostra il tuo animo pieghi / a dirne chi tu se” (then may our fame incline your mind / to tell us who you are [Inf. 16.31-2]). And, in presenting his comrades, Iacopo speaks of Guido Guerra using the term “grado” (degree), a word that is redolent of social hierarchy and rank. Iacopo insists that Guido Guerra was “higher in degree than you believe”: “fu di grado maggior che tu non credi” (Inf. 16.36).

[18] The key thematic indicator is Virgilio’s adjective cortese — “a costor si vuole esser cortese” (to these one must show courtesy [Inf. 16.15]) — reprised in the all-important noun cortesia in verse 67. The noble Florentines ask Dante about the current state of their city, and frame their query in terms of courtly values, “cortesia e valor” (courtesy and valor [67]):

«Se lungamente l’anima conduca le membra tue», rispuose quelli ancora, «e se la fama tua dopo te luca, cortesia e valor dì se dimora ne la nostra città sì come suole, o se del tutto se n’è gita fora...» (Inf. 16.64-69)

“So may your soul long lead your limbs and may your fame shine after you,” he answered then, “tell us if courtesy and valor still abide within our city as they did when we were there or have they disappeared completely...”

[19] Dante is here thematizing not just the urban politics of his native city, but the character and fiber of its highest citizens. He measures them by the knightly and feudal code of cortesia (not just “courtesy” but “courtliness”), as inherited in Tuscany from the Sicilian and Occitan courts, and as sung by poets of old.

[20] This courtly world — not the urban and mercantile world of contemporary Florence but an older world that contemporary Florentines held in aspirational esteem — is evoked in Iacopo’s pointed query about the continued presence of “cortesia e valor” (courtesy and valor) in contemporary Florentine society: “cortesia e valor dì se dimora / ne la nostra città si come suole” (tell us if courtesy and valor still / abide within our city as they did [Inf. 16.67-68]). Knighthood, hearkening back to the feudal world of cortesia, was still a criterion of nobility, as we see in the passages from historian Carol Lansing’s The Florentine Magnates cited in the Commento on Inferno 10.

[21] And it was invoked in aspirational terms by poets and writers. For instance, the poet Folgore da San Gimignano, whose dates of 1270-ca. 1332 make him a contemporary of Dante, celebrates in one sonnet cycle (Semana) the days of the week in the life of a young donzello (a youth preparing to be a knight), and in another sonnet cycle (Mesi) the life of a “brigata nobile e cortese” (Dedica alla brigata, 1). For more on the aspirational cortesia evident in literary texts of Dante’s period, see my essay “Sociology of the Brigata,” cited in Coordinated Reading.

[22] Dante replies to Iacopo’s query with his very personal analysis of what has been the cause of Florentine corruption. He believes that the city has been destabilized by new people with their new money: “La gente nuova e i sùbiti guadagni” (Newcomers to the city and quick gains [Inf. 16.73]). Dante here blames the decay of Florentine cortesia on the nouveaux riches who have changed the dynamics within the city, bringing “arrogance and excess” — “orgoglio e dismisura” — to its citizenry:

«La gente nuova e i sùbiti guadagni orgoglio e dismisura han generata, Fiorenza, in te, sì che tu già ten piagni». (Inf. 16.73-75)

“Newcomers to the city and quick gains have brought excess and arrogance to you, o Florence, and you weep for it already!”

[23] By what route does Dante arrive at the political analysis of Florentine corruption that we find in Inferno 16? If we trace Dante’s thought process as a political theorist, we find that there are fascinating contradictions embedded in Inferno 16’s castigation of new people with their new money. For Dante had earlier refuted passionately and at length the theory whereby old money confers nobility.

[24] Circa 1294, in the canzone Le dolci rime (a canzone whose Aristotelian ethical framework reflects Brunetto Latini’s translation of Aristotle’s Ethics, as discussed in the Commento on Inferno 15), Dante claims that true nobility resides in virtue, not in lineage, and certainly not in ancestral wealth.

[25] Wealth accumulated over many generations is, in the theory Dante puts forward in the canzone of the mid-1290s, not a factor in an individual’s nobility. In Le dolci rime Dante specifically takes aim at what he considers Frederick II’s definition of nobility, whereby nobility is composed of the amalgam of old money and good manners: “antica possession d’avere / con reggimenti belli” (ancestral wealth / together with fine manners [Le dolci rime, 23-24; trans. Richard Lansing]). He mocks those who think that they derive worth and nobility from inherited wealth and status:

ed è tanto durata la così falsa oppinion tra nui, che l’uom chiama colui omo gentil che può dicere: ‘Io fui nepote, o figlio, di cotal valente’, benché sia da niente. (Le dolci rime, 32-37

And so ingrained has this false view become among us that one calls another noble if he can say “I am the son, or grandson, of such and such worthy man”, despite being himself nothing. (Trans. Richard Lansing, from his Convivio, modified by TB)

[26] In another moral canzone of the mid-1290s, Poscia ch’Amor (circa 1295), Dante pivots from theory to praxis, elaborating on behavioral aspects that are unexplored by the theoretical discourse of le dolci rime. Here he poses questions about how the cavalieri (knights) who are the canzone’s target audience are supposed to behave in day-to-day life. With respect to Dante’s polemical affirmation, in Le dolci rime, that nobility is not defined as “antica possession d’avere / con reggimenti belli”, Poscia ch’Amor considers the “reggimenti belli”: what are the behaviors that a cavaliere should possess and what are they not? How should he dress (we remember that Dante is recognized in this canto by his dress), how should he speak, how should he pay court to ladies, and — perhaps most importantly — how should he spend his money?

[27] As we have seen, in Le dolci rime Dante states openly and resolutely that ancestral wealth does not confer nobility. Wealth accumulated over many generations is not a factor in an individual’s nobility; in other words, the possession of wealth by a lineage over many generations does not ipso facto confer nobility on that lineage. This is a seriously radical position in Dante’s time; even today, what we still call “old money” continues to exert a non-negligible sway in society.

[28] In Inferno 16 Dante veers away from the position of the canzone, a position that he had subsequently reiterated about a decade later in the philosophical treatise Convivio. And he does so in a way that necessarily recalls the very canzone whose radical views he is no longer able to embrace. In Le dolci rime, the importance of holding wealth over time is signalled with the temporal adjective “antica” (ancient, old): “antica possession d’avere” (literally, ancient possession of wealth [Le dolci rime, 23]). In Inferno 16 Dante substitutes the adjective “antica” that qualifies wealth in Le dolci rime, the adjective that communicates the importance of holding wealth over time, with the opposite temporal adjective: now the castigated riches are those that are “sùbiti guadagni” (quick gains, literally “sudden earnings”).

[29] In Le dolci rime Dante’s point is that even the antiquity of one’s wealth cannot elevate it into the crucible of genuine nobility. In Inferno 16 Dante’s view has shifted in a significant way, as signalled by the presence of two temporal adjectives that are the opposite of antico: nuovo and sùbito. Now he is saying that the newly minted material riches of the new families — “la gente nuova” — of contemporary Florence are to be denigrated precisely because they are “sudden” and “immediate” and not ancient: “i sùbiti guadagni” (quick gains [Inf. 16.73]).

[30] In Le dolci rime the temporal adjective antico is not derogatory. It is simply a statement about insufficiency: antiquity of wealth is not enough to confer nobility. In Inferno 16, by contrast, the temporal adjectives nuovo and sùbito are derogatory. Dante is no longer the young man sustained by youthful ideals of virtue with respect to social class. He seems now to have a greater appreciation of the old families, if only because he is more threatened by the gente nuova, the new merchant class which he projects as a threat onto Fiorenza herself in the pilgrim’s apostrophe to the city.

[31] Dante’s attack on the new people and new money who bring “arrogance and excess” into the city suggests that he experienced the newly-minted wealthy of Florence as more threatening to him, with respect to his personal status, than the older aristocracy. His own social position as a member of a non-wealthy family that claimed noble antecedents was rather precarious, and it must have been difficult for Dante, the greatly ambitious scion of a somewhat marginal family, to watch the speedy rise of pretentious insurgents.

[32] Dante’s sensitivity to the gente nuova would undoubtedly have been exacerbated by the decline of his family’s fortunes, a decline traced by Enrico Faini in “Ruolo sociale e memoria degli Alighieri prima di Dante,” cited in Coordinated Reading. As Faini shows, Dante’s ancestors had achieved aristocratic status in the time of Cacciaguida and Alighiero I, while Dante’s branch of the family lost noble standing in the succeeding decades. The circumstances of Dante’s marriage to Gemma Donati, as discussed by Isabelle Chabot (cited in Coordinated Reading), are also worth considering in this context. Despite her lineage, Gemma Donati brought a very small dowry into her marriage. On this basis Chabot puts Gemma’s father Manetto Donati, despite his Donati affiliation, in the same category of “mediocritas” (mediocrity) as Dante’s father:

Lui era figlio di un mediocre campsor; lei, certo, apparteneva a una famiglia dell’antica aristocrazia cittadina. Ma se il padre di lei, Manetto Donati, non era in grado di sborsare più di 200 lire per darla in sposa, evidentemente condivideva con Alighiero la stessa mediocritas. (Chabot, “Il matrimonio di Dante,” p. 10).

He was the son of a middling money-changer; she, certainly, belonged to a family of the city’s ancient aristocracy. But if her father, Manetto Donati, was not in a position to disburse more than 200 lire to give her in marriage, evidently he shared the mediocritas of Alighiero.

[33] A brilliant and ambitious man of Dante’s precarious social standing would clearly find attractive the idea that nobility is not connected to wealth and social status, but is instead infused directly by God. This idea, originally developed by Dante in the canzone Le dolci rime following in the wake of Guido Guinizzelli’s canzone Al cor gentil, is present in the Commedia as well. There is a strong endorsement of this view for instance in Purgatorio 7, where we learn that virtue comes from the transcendent principle, not from lineage:

Rade volte risurge per li rami l’umana probitate; e questo vole quei che la dà, perché da lui si chiami.(Purg. 7.121-23)

How seldom human worth ascends from branch to branch, and this is willed by Him who grants that gift, that one may pray to Him for it!

[34] But, at the same time, the variegated social tapestry of the Commedia triggers complex reactions in Dante, which lead to some privileging of ancient lineage over the despised nouveaux riches, whom he deplores again in Paradiso 16. As we have seen, Dante’s dislike of the rich Florentines who had no nobility, no leggiadria (the virtue of a cavaliere, denoting grace and physical presence), dates back to the canzone Poscia ch’Amor. This dislike emerges supercharged in Inferno 16, fueled by a new ideology against the gente nuova and their sùbiti guadagni.

[35] Contradictions abound, too, between the values of feudal cortesia, which place a premium on spending money with largesse, and those of bourgeois (and Aristotelian) moderation. In the essay “Dante on Wealth and Society, Between Aristotle and Cortesia: From the Moral Canzoni Le dolci rime and Poscia ch’Amor through Convivio to Inferno 6 and 7″ (cited in Coordinated Reading), I discuss some of the ways in which Dante experienced himself and his society as buffeted by these divergent philosophies of wealth and social standing.

[36] Courts and the cult of cortesia are aspirational in some contexts, destructive in others. The story of the grifter Ciampolo in Inferno 22 offers insight into the ethical challenges faced by the hangers-on who live in the margins of a great court. Ciampolo’s tale highlights the pressures of a life-style in which financial prudence was much less valued than largesse in spending. On the other hand, in Purgatorio 8 Dante celebrates the Malaspina family for their aristocratic “pregio de la borsa” (Purg. 8.129). The “glory of their purse” refers to the Malaspina magnificence in spending. They display the courtly largesse that befits great lords, according to a courtly ideology.

[37] Dante’s attack focused on the new people of Florence is based on an ideological assumption of their “arrogance and excess”: the “orgoglio e dismisura” with which they have corrupted Dante’s beloved birthplace. The word “dismisura” is important: as discussed in the Commento on Inferno 11, dismisura is the vernacular equivalent of the Aristotelian concept of “incontinenza” or excess (Inf. 11.82 and 83). Dismisura is lack of misura: lack of measure, hence excess. In Inferno 7, Dante defines misers and spendthrifts as those who spent without misura, which is tantamount to saying “with dismisura”: “che con misura nullo spendio ferci” (no spending that they did was done with measure [Inf. 7.42]). Dismisura in Dante’s usage becomes an umbrella term embracing the wide-ranging sickness of overheated and intemperate desire captured in the Christian concept of cupidigia (see Inferno 12 and the lupa of Inferno 1) and in the Aristotelian concept of incontinenza. The term dismisura appears only twice in the Commedia; besides Inferno 16, the other use occurs appropriately on Purgatory’s terrace of avarice and prodigality (in Purgatorio 22.35).

[38] Dante is working to reveal the common ground of excess or dismisura that underlies all the sins of incontinence, as he had begun to do years before in the canzone Doglia mi reca (see “Guittone’s Ora parrà, Dante’s Doglia mi reca, and the Commedia’s Anatomy of Desire,” cited in Coordinated Reading). Far from viewing dismisura as most applicable to sexual behavior, Dante’s focus with respect to dismisura had been for years, going back to his moral canzoni, on wealth and wealth management.

***

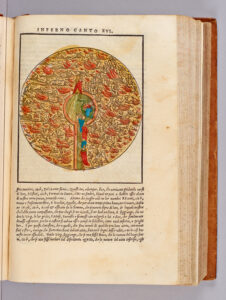

[39] While I have focused in this Introduction on the issues of wealth and cortesia, Inferno 16 also thematizes narrative transition, dwelling on the nature of the pilgrim’s very special journey and that of the very special poem that recounts it. All this will culminate in the complicated verses that declare this poem a “comedìa” (verse 128). If I devote less attention to the word comedìa than to the word dismisura in this Introduction, it is because I have written so much on comedìa in the past, in both Dante’s Poets and The Undivine Comedy. I therefore send the reader who would like a less cursory treatment of Geryon’s arrival and its manifold implications to my books and the pages from them that are cited in Coordinated Reading.

[40] Inferno 16’s transitional concerns, which dominate the last section of the canto, begin to manifest in the particularly complete and forward-looking justification of his journey offered by the pilgrim to the Florentine sodomites in verses 61-63: “Lascio lo fele e vo per dolci pomi / promessi a me per lo verace duca; / ma ’nfino al centro pria convien ch’i’ tomi” (I leave the gall and go for the sweet apples / that I was promised by my truthful guide; / but first I must descend into the center [Inf. 16.61-3]). Also noteworthy is the sodomites’ address to Dante, their equally farsighted anticipation of Inferno’s last verse and reference to a future when the pilgrim will look back on this present as the past: “Però, se campi d’esti luoghi bui / e torni a riveder le belle stelle, / quando ti gioverà dicere ‘I’ fui’” (So, if you can escape these lands of darkness / and see the lovely stars on your return, / when you repeat with pleasure, ‘I was there’ [Inf. 16.82-85]).

[41] In the above verses the Florentine sodomites recognize Dante-pilgrim’s uncommon existential status: he is someone who can say that he was in Hell but is no longer. He can literally put Hell into the past tense, and use the past absolute to say “I was there”: “I’ fui” (Inf. 16.85). He will return to see the beautiful stars — “e torni a riveder le belle stelle” — that the poet features as the Inferno’s last word. In this way the Florentine sodomites prepare for the existential and voyaging thematics of Inferno 16’s final section.

[42] Beginning in Inferno 16.91, the narrator’s attention turns to the waterfall over the abyss, first mentioned in the first verse of this canto. The intercalatory “spiral” narrative structure of these canti is analyzed in The Undivine Comedy, Chapter 3, “Ulysses, Geryon, and the Aeronautics of Narrative Transition”. As at the end of Inferno 8, the action will be suspended at the end of Inferno 16 and reprised in medias res at the beginning of Inferno 17. A full rehearsal of the narrative elements is available in the Commento on Inferno 17.

[43] The narrator now turns to the strange arrival of the flying monster who will serve as the vehicle on which the travelers descend to the eighth circle; this is Geryon. The most remarkable feature of the verses that introduce Geryon is that Dante chooses them also to baptize his poem, named as “questa comedìa” (this comedy) in Inferno 16.128:

Sempre a quel ver c’ha faccia di menzogna de’ l’uom chiuder le labbra fin ch’el puote, però che sanza colpa fa vergogna; ma qui tacer nol posso; e per le note di questa comedìa, lettor, ti giuro, s’elle non sien di lunga grazia vòte, ch’i’vidi per quell’aere grosso e scuro venir notando una figura in suso, maravigliosa ad ogne cor sicuro... (Inf. 16.124-32)

Faced with that truth which seems a lie, a man should always close his lips as long as he can— to tell it shames him, even though he's blameless; but here I can't be still; and by the lines of this my comedy, reader, I swear— and may my verse find favor for long years— that through the dense and darkened air I saw a figure swimming, rising up, enough to bring amazement to the firmest heart...

[44] In this passage, for the first time, Dante refers to his poem as a comedìa. The only other use of the word comedìa in this poem will occur in Inferno 21. Very significantly, in this passage Dante links comedìa to the concept of “that truth that has the face of a lie”: “quel ver c’ha faccia di menzogna” (Inf. 16.124). As I write in Dante’s Poets:

Dante here lets us know that he doesn’t expect us to believe his account of what he saw, but that nonetheless we must, for his story is “quel ver c’ha faccia di menzogna” — a truth which has the appearance of a lie. Because we are not likely to believe this lying truth, he resorts to an oath, swearing by the notes of his poem, “questa comedia,” that he in fact saw what he says he saw: “e per le note / di questa comedia, lettor, ti giuro . . . ch’i’ vidi” (and by the notes of this comedy, reader, I swear to you . . . that I saw [Inf. XVI, 127-30]). What has not been sufficiently recognized is that the poem is here defined, not only as a comedia, but also as “quel ver c’ha faccia di menzogna,” and that this last phrase is nothing but a gloss for the first: a comedia is that truth which has the appearance of a lie but which is nonetheless always a truth. If the Aeneid is a tragedia instead, according to the definition offered in Inferno XX, this is because it is the opposite of the Comedy: a truthful lie, rather than a lying truth. (Dante’s Poets, pp. 213-14)

[45] In effect, Dante in this passage both uses the word comedìa for the first time and defines it: comedìa is truth that has the appearance of a lie but that is nonetheless always a truth.

[46] Dante here swears that the “marvelous” and in-credible being that he saw swimming out of the murky deep is absolutely and incontrovertibly true. He affirms this truth with an oath taken on the very notes of the poem that he is writing, an oath whose stakes are nothing less than the “lunga grazia” that he hopes his poem will achieve among its readers:

e per le note di questa comedìa, lettor, ti giuro, s’elle non sien di lunga grazia vòte (Inf. 16.127-29)

and by the lines of this my comedy, reader, I swear — and may my verse find favor for long years —

[49] In other words, Dante seeks long life for his comedìa. This prayer for long life for his poem recalls Inferno 15 and Brunetto’s “nel qual io vivo ancora” (in which I still live [Inf. 15.120]) and reminds us that we must be careful not to discount the value of literary fame for this poet.

[50] Dante uses Geryon’s arrival to place the issue of true claims front and center. As I write in The Undivine Comedy: “Geryon serves as an outrageously paradoxical authenticating device: one that, by being so overtly inauthentic, so literally a figure for inauthenticity, a figure for ‘fraud’, confronts and attempts to defuse the belatedness or inauthenticity to which the need for an authenticating device necessarily testifies” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 59). With respect to the oxymoronic juxtaposition of “maravigliosa” (marvelous) with “io vidi” (I saw) in verses 130 and 132 cited above, I note: “Far from giving quarter, from backing off when the materia being represented is too ‘maravigliosa’ to be credible, Dante raises the ante by using such moments to underscore his poem’s veracity, its status as historical scribal record of what he saw” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 60).

[51] As a general principle, Dante “neutralizes the betrayal of self-consciousness implicit in all narrative authenticating devices by making his authenticating devices outrageously inauthentic” (The Undivine Comedy, p. 15). This is the principle that I call the “Geryon principle” in The Undivine Comedy (pp. 15, 59-60, 90, 98, and 271, note 33). The first manifestation of the principle is at the end of Inferno 16; for other examples, see Inferno 25, Inferno 28, and Inferno 34.

[52] Dante’s term comedìa thus both vindicates the prophetic truth of his vision and confronts the necessary quotient of deceit embedded in all human language.

Return to top

Return to top