Paradiso 7 begins with Justinian’s prayer, in a divine mixture of Hebrew and Latin. Here it is, preserved by Mandelbaum untranslated, in order to render the combination of Latin and Hebrew, unique in the Commedia:

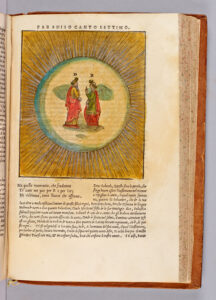

Osanna, sanctus Deus sabaòth, superillustrans claritate tua felices ignes horum malacòth. (Par. 7.1-3)

Sapegno glosses the verses in his commentary thus: “Salve, o santo Dio degli eserciti, che illumini dall’alto con la tua sovrabbondante luce i beati splendori di questi regni celesti” (Hosanna, o holy God of the armies, who illuminate from on high with your superabundant light the blessed splendors of this celestial realm).

In discussing the monstrous language used by Plutus at the beginning of Inferno 7, I alluded to the instability caused by the melding of Dante’s committed and muscular Christianity with his pre-humanism. On the one hand, Dante praises and cites Aristotle and Vergil and he constantly uses and cites the Bible. On the other hand, he simultaneously makes Plutus’s degraded language of Inferno 7 out of Hebrew and Greek, based on the rudimentary knowledge of these languages that he obtained from medieval glossaries.

In Paradiso 7, Justinian’s celestial language is similarly concocted, from Hebrew and Latin. Perhaps there is a certain amount of cognitive dissonance in Dante’s thinking about the makers of these languages. More likely, he thought in terms of Hebrew, Latin, and Greek being used in malo in Inferno 7 and used in bono in Paradiso 7, and he demonstrates both practices.

Paradiso 7 begins with a celestial language that includes Hebrew words; it also includes the charge of deicide leveled against the Jews. This charge is central to Providential history as Dante expounds it in Paradiso 5, Paradiso 6, and Paradiso 7. The charge of Paradiso 7 is embedded within a vision of history that Dante fully accepts. Perhaps one could infer some lack of complacency from Dante’s need to buttress the “legality” of that vision, dramatized through the choice of Justinian, the codifier of law, as presenter of the concept of the “vendetta . . . / de la vendetta del peccato antico” (Par. 6.92-93).

Paradiso 7 recounts a very different kind of history from the previous canto, though linked both substantively and rhetorically by the crucifixion of Christ as a punishment for mankind’s original transgression. The link to Paradiso 6 is stated by Beatrice, according to her “infallible judgment”, in Paradiso 7.20-21:

Secondo mio infallibile avviso, come giusta vendetta giustamente punita fosse, t’ha in pensier miso (Par. 7.19-21)

According to my never-erring judgment, the question that perplexes you is how just vengeance can deserve just punishment

Let me digress briefly from the problem posed about “just vengeance” to mention that the use of the adjective “infallible” in the above terzina for female speech is stunning, given the long and documented tradition of female speech as the special focus and target of misogyny. Beatrice’s “secondo mio infallibile avviso” (According to my infallible judgment [Par. 7.19]) constitutes the Commedia’s only use of “infallibile” for human speech of any sort, male or female. On the significance of this usage, see my “Notes toward a Gendered History of Italian Literature, with a Discussion of Dante’s Beatrix Loquax”, cited in Coordinated Reading, p. 368.

The question that perplexes the pilgrim is: How can a just punishment be justly punished? In other words, if it was just to kill Christ, how can it have been just to punish the Jews for killing Christ?

The answer requires a somber and poetically very beautiful Dantean retelling of the fundamental Christian narrative: the story of how Adam sinned and of how Christ died to redeem Adam’s sin. In terms of the polarities of Paradiso that we have been discussing, this canto skews toward the Augustinian rather than toward the Aristotelian. Difference is viewed negatively in Paradiso 7, rather than positively.

Paradiso 7 does not offer the vindication of the necessity of difference that we saw in Paradiso 2, where Dante insists on difference as a “principio formal” — an essential principle — of God’s creation. Rather, it focuses on how mankind became different from God through sin.

Thus, Paradiso 7 offers a theological discussion of the process through which we became different from God and unlike God: the process whereby we entered what Augustine calls the regio dissimilitudinis (the region of unlikeness).

What follows is a breakdown of Beatrice’s discourse.

Paradiso 7.25-33: Adam damned himself by accepting no limits to his will. In the Ulyssean lexicon that Dante overlays onto the Adamic myth, Ulysses damned himself through his “folle volo” (Inf. 26.125). The word “follia” will be used for mankind’s sin in Paradiso 7.93. In damning himself, Adam damned all his progeny. As a result, mankind lived in great error until it pleased the second person of the Trinity (“the Verb of God”) to descend and to unite to Himself the human nature that had so distanced itself from God. Hence, God became man in the person of Christ.

Paradiso 7.34-51: The dual nature of Christ (a discussion prefigured by Justinian’s conversion to belief in Christ’s dual nature; see Paradiso 6.13-21; this in turn is prefigured by Paradiso 2.42, “come nostra natura a Dio s’unìo”) provides the distinction that helps to “resolve” the apparent contradiction of the just punishment that is justly punished. In as much as we are speaking of Christ’s human nature, the punishment of the Crucifixion was merited; in as much as we are speaking of Christ’s divine nature, it was not. The result is an action, the killing of Christ, which pleased both God and the Jews — but for different reasons: “ch’a Dio e a’ Giudei piacque una morte” (one death pleased both God and the Jews [Par. 7.47]). God was pleased in that human beings were justly punished, and the Jews were pleased because they considered blasphemous Christ’s claim to be Son of God and Messiah.

Paradiso 7.52-64: Dante does not understand why God willed our redemption to take place in the arduous way that he chose: “perché Dio volesse . . . / a nostra redenzion pur questo modo” (56-57). What follows is the “explanation”.

Paradiso 7.64-78: On a backdrop of creation theology — verses 64-66 are a medieval description of the Big Bang — Beatrice explains that God created humans directly, without mediation (“sanza mezzo”). Our im-mediate or un-mediated creation by God (similarly, God directly breathes life and soul into the human embryo in Purgatorio 25) is a joyous interlude in the tragic story of the fall that Beatrice is recounting, for that which is created “im-mediately” by God receives from Him the gifts of eternity, liberty, and conformity:

Ciò che da lei sanza mezzo distilla non ha poi fine, perché non si move la sua imprenta quand’ella sigilla. Ciò che da essa sanza mezzo piove libero è tutto, perché non soggiace a la virtute de le cose nove. (Par. 7.67-72)

All that derives directly from this Goodness is everlasting, since the seal of Goodness impresses an imprint that never alters. Whatever rains from It immediately is fully free, for it is not constrained by any influence of other things.

These exceptionally beautiful lines affirm in solemn cadences that what is made directly by God is immortal — “non ha poi fine” (it has no end [Par. 7.68]) — and free: “libero è tutto” (is fully free [Par. 7.71]). Our immortality is the result of being created directly by God, as is our liberty. We are free because we are not subject to the power of the heavens: the “new things” of Paradiso 7.72.

Why are the heavens called “cose nove” — “new things”? They are “new” because they themselves were created by God, Who alone is not new and never saw anything new (because He sees everything all at once): “Colui che mai non vide cosa nova” (He Who never saw a new thing [Purg. 10.94]). The heaves were created, hence they are new. They themselves were created directly, and therefore (as we learn at the end of the canto), they are not corruptible. But what the heavens themselves generate was not created directly, and therefore is corruptible.

The heavens can influence our behavior but cannot determine it. This crucial truth was first affirmed by Marco Lombardo in Purgatorio 16 and was subsequently reaffirmed by Beatrice in Paradiso 4. The verb soggiacere in “non soggiace / a la virtute de le cose nove” (it is not subject to the power of the new things [Par. 7.71-72]) recalls the paradox of free will and our willing subjection to God as expressed by Marco Lombado with the same verb, soggiacere: “liberi soggiacete” (you are freely subject [Purg. 16.80]).

Our immortality and our freedom as creatures created directly by God is the good news. The good news however turns bad. Humans did indeed receive these gifts. But we lost these original gifts as a result of original sin, which caused us to fall from our native nobility.

Paradiso 7.79-120: Sin is what un-frees humans, and makes us dissimilar to God; we will never return to our original dignity unless we fill where sin has emptied. That can be done either by God forgiving us, or by humans on our own paying back the debt (91-93). But we don’t have the means to make reparations on our own, so God has to use his methods to restore mankind “to his full life”: “a sua intera vita” (104). God’s methods are two: the way of mercy and the way of justice. He decides to use both (“di proceder per tutte le sue vie”, verse 110). There is no greater event in all of time (112-113) than the one in which God gives Himself in order to raise mankind back up to the position from which we fell.

Paradiso 7.121-148: Going back to the theme of creation, Beatrice adds a corollary that clarifies and reinforces mankind’s position as a being created directly by God. Even our bodies are created directly by God; from this fact we can deduce our resurrections.

The strangely “happy” ending to a theologically gloomy canto is captured by the joyfulness of the linguistic play on “d” in Paradiso 7.10-12, which echo a similar play in Paradiso 5.119-23:

e però, se disii di noi chiarirti, a tuo piacer ti sazia.» Così da un di quelli spirti pii detto mi fu; e da Beatrice: «Dì, dì sicuramente, e credi come a dii.» (Par. 5.119-23)

thus, if you would know us, sate yourself as you may please.” So did one of those pious spirits speak to me. And Beatrice then urged: “Speak, speak confidently; trust them as you trust gods.”

Io dubitava e dicea «Dille, dille!» fra me, «dille», dicea, «a la mia donna che mi diseta con le dolci stille».(Par. 7.10-12)

I was perplexed, and to myself, I said: “Tell her! Tell her! Tell her, the lady who can slake my thirst with her sweet drops.”

The poet’s play on the “d” sound connects the urgency of speech — “Dì, dì / sicuramente” (Par. 5.122-23) and “Dille, dille!” (Par. 7.10) — with the urgency of the desire to know: “se disii / di noi chiarirti” (Par. 5.119-20). And this desire further connects us to God: “e credi come a dii” (Par. 5.123). In these luminous and playful verses disio is not transgressive. Disio and dire are here joined in a happy delirium of expression and sweetness that seems to belong to a different universe from Adam’s sin.

Return to top

Return to top